Valuation Basics (Study Guide)

advertisement

1

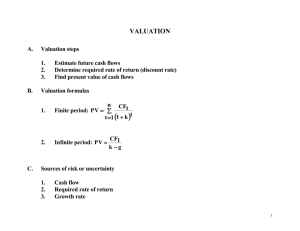

VALUATION BASICS

There are three basic approaches to asset valuation in a free enterprise

economy. The first (the asset value) assumes the asset is worth its book value (what

shows on the annual report or other corporate financial reports), the cost of

recreating it (replacement value), or the returns from liquidating it (liquidation

value). The second (the market value) assumes that an asset is worth what someone

else will pay for it. The third (the income value) assumes that the asset’s value is the

sum of the benefits it will produce during its life. There are other ways of

evaluating the attractiveness of an asset, and these ways will be considered later.

We will not spend much time discussing the asset method except to note that,

in the case of companies, divisions, joint ventures, and the like, the asset value

includes the value of intangibles such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and good

will as well as the value of tangible assets such as accounts receivable, inventory and

fixed assets. Both tangible and intangible assets are usually estimated at their market

or replacement values, but establishing market value for intangible assets represents

a significant challenge. In many cases, the income or market methods may be used

to value intangibles. In turnaround or bankruptcy situations, as well as some

ordinary lending situations, liquidation value is calculated.

THE INCOME METHOD

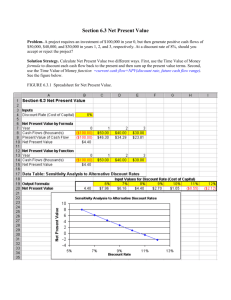

The present value (PV) model discounts (reduces) the free cash flow (FCF)

and terminal value (TV) expected from an investment. When net present value

(NPV) is wanted, the initial outlay (Co) is subtracted from the PV. FCF and TV are

discounted because the promise of future payments is worth less than cash in hand

now. If NPV > 0, or PV > Co, the asset will make an economic profit (called

economic rent or just rent) and is seen to be financially attractive although not

necessarily strategically appropriate.

2

FCFs may take a number of forms with the PV calculated in different ways

(assuming end-of-period payment). The notations are as follows:

i = discount rate or cost of capital.

g = future growth rate of FCF

1. An annuity where a constant payment is offered in perpetuity: FCF / i

2. A growing annuity in perpetuity: FCF / (i – g)

3. An annuity in perpetuity beginning in some future period, say t = 4:

(FCF4 / i) / (1+i)3

FCF4 / i discounts the FCF to the beginning of period 4 / end of period 3.

(1 + i)3 discounts it back to the end of time period 0 / beginning of time

period 1.

4. A growing annuity in perpetuity starting in some future period, say t = 4:

FCF4 / (i – g) / (1 + i)3 OR FCF4 / (i * (1+i)3).

Often, FCF is forecast using the previous period’s FCF. Then [FCF3 *

(1+g)] = FCF4.

5. FCFs vary from time period to time period ending with a final value, the

terminal value (TV). This is called a two-stage model. Three and fourstage models may be constructed using different time periods and

different discount rates:

PV = FCF1 + FCF2 + FCF3 +….+ FCFn

(1 + i)

Where:

(1 + i)2 (1 + i)3

(1 + i)n

+ TVn

(1 + i)n

3

FCF = free cash flow to capital consisting of earnings before interest and

after taxes (EBIAT) plus depreciation minus change in working

capital minus new investments. These are funds available to pay

suppliers of debt and equity during the period covered. An

alternative calculation is EBIAT minus change in working capital

minus change in net investments (change in investments after

accumulated depreciation is subtracted from the periods being

studied). The latter is helpful if the data do not show depreciation

and gross investment separately.

i

= cost of capital, opportunity cost of capital, hurdle rate, or discount

rate. The rate discounts FCF for liquidity preference (real rate of

interest), inflation, investment (or maturity) risk, and market risk.

1,2,3 = time, usually in years, beginning at time 0 with the designation Co.

Often, the assumption is made that all cash flows occur at the end of

the time period. However, you can calculate PV when the cash

flows occur at different time periods by manipulating the power. If

you use the more reasonable mid-year convention (all cash flows

occur during the middle of the year) and your beginning date is the

end of a year, you would take one plus the discount rate to the

power of 0.5, 1.5, 2.5 and so on.

n

= the last period of the planning horizon (often 5th or 10th year,

or when competition is expected to reduce future NPV to

zero).

TV

= terminal value; value at the end of the planning horizon. The

growing annuity in perpetuity discussed in (4) above is often used

to estimate this value. This perpetuity model is generally referred

to as the Gordon Growth Model.

4

The strengths of this method are its emphasis on costs and benefits and its rigor. The

major weakness is the requirement for forecasting.

MORE ON FREE CASH FLOW

FCF for debt is the interest paid on a periodic basis—monthly, quarterly, biannually, or annually. FCF to equity holders (common and preferred stock) is the

dividend payment plus or minus the capital gains or losses in the market value of the

stock over the given time period. You must also account for stock splits when they

occur by multiplying the dividend and the stock price after the split by the amount of

the split. If the stock were split two for one during the period measured but prior to

the dividend being issued, you would multiply the dividend and the end-of-period

stock value by two. If the dividend had already been paid, you would only multiply

the stock value by two.

Developing a forecast of company FCF requires an understanding of what

income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements really mean, how they

are constructed, and how they are forecast. An income statement calculated on the

accrual basis shows how much it costs to produce goods and services that are

shipped (producing revenues) during a specific period of time. Typically, the

moment a product leaves the shipping dock (or a service is provided), or the product

arrives at its destination (FOB Destination) a sale is recorded. If the sale is on credit,

an account receivable is created. Exceptions to the shipped assumption include

progress payments on large items under construction (such as airplanes) and on

services provided over time.

Income Statement Items

The income statement used for financial analysis differs somewhat from the

income statement found on the usual annual report. For purposes of discounting,

financial analysts often use earnings before interest after taxes (EBIAT) rather than

net income. They separate operating cash flow from financing cash flow, while the

5

preparers of the income statement do not. Financial analysts separate operations and

finance because the effect of interest is accounted for in the discount rate (discussed

below) and should not be double counted. Table 1 demonstrates the difference.

TABLE 1. ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE DIFFERENCES

Time Period

Time Period

1

1

Accounting

Finance

Revenue (Net Sales)

1,000

1,000

Cost of Goods Sold

(500)

(500)

500

500

(150)

(150)

350

350

(100)

(100)

250

250

Gross Profit

Operating Expenses

EBITDA

Depreciation/Amortization

EBIT

Corporate Taxes @ .40

(100)

EBIAT

150

Interest

(50)

Profit Before Taxes

200

Corporate Taxes @ .40

(80)

Interest Tax Shield

Net Income (PAT)

(50)

20

120

120

The interest tax shield (ITS) is found by multiplying interest bearing debt * cost

of debt * marginal tax rate. The marginal tax rate is the incremental tax you pay

(expressed as a percentage) because you choose to make the investment. In the

above illustration, it is 40%.

6

Balance Sheet Items

The balance sheet shows the book value of assets required to support the

sales revenues and how those revenues are financed by liabilities and equity (net

worth).

In finance, working capital is the difference between current operating assets

(usually required operating cash, accounts receivable, and inventory) and current

operating liabilities (usually accounts payable to vendors or ‘the trade’, accrued

expenses such as payroll expenses and other costs that have been incurred but not yet

paid, and accrued taxes). Excess cash is excluded since it is not essential for

operations and it is the operating entity that is being valued. Current interest-bearing

debt usually is not included since it is not part of the operations of the company

(although, as mentioned above, there is significant disagreement about whether all

current interest bearing debt should be excluded). For our purposes, we will assume

that all interest-bearing debt is excluded. Non-operating assets and liabilities are

valued separately and added to the value of operating assets.

Tangible assets with a life of more than a year are depreciated as of the time

they are put into use. (However, current tax law allows you to expense up to

$500,000 in tangible assets per year.) Intangible assets such as patents, copyrights,

trademarks, and service marks are amortized. Goodwill is the difference between

the firm or project’s market value and the tangible and intangible assets that can be

valued individually. Depreciation and amortization may be deduced for tax purposes

with the exception of goodwill. Net tangible assets are assets after accumulated

depreciation and amortization.

The book value of an asset, liability, or equity is not usually the same as the

real or market value. Adjustments need to be made before an analysis is undertaken.

Accountants usually value balance sheet items at cost or market; whichever is

lower—although this is changing. Financial analysts use the market values of these

items.

7

Sometimes, it is enough to assume that book values equal market values, but

exceptions occur when, for example, some accounts receivable are not collectable,

inventories are outdated or damaged, fixed assets are rapidly depreciated below their

actual market value or have become obsolete. On the opposite side of the balance

sheet, bond and preferred stock values change with the market. Book values of

common stocks are often significantly different from their market values.

Free Cash Flow (FCF)

A cash flow statement shows how cash flows into and out of an organization

over a time period. Financial analysts are interested in cash flow because only cash

can be used to pay bills, purchase assets, pay dividends and interest, or pay off debt

and repurchase equity. You cannot pay shareholders, creditors, or anyone else with

profits.

There is a difference between profits and cash flow. Not appreciating this

difference has cost many people their businesses. Just because the company is

making an adequate profit does not mean that it will survive and prosper. It must

also provide for new capital investment (CAPX), working capital (the difference

between current operating assets and current operating liabilities), interest and

dividends.

Cash flow is a general term with several definitions. FCF is Earnings before

interest after taxes (EBIAT) + Depreciation, Amortization of intangibles except good

will, Deferred Taxes, Write-downs, and Other Non-Cash Charges – Periodic

(annual) change in operating working capital – Periodic (annual) change in gross

investments (CAPX) - Periodic (annual) changes in capitalized operating leases –

Investment in Goodwill. The worth of capitalized leases is found by calculating the

present value of future lease payments.

Depreciation, amortization of intangibles except good will, and other noncash charges, being tax deductible, are subtracted from revenues just like other costs

to get EBIAT. However, they must be added back because they are non-cash. An

alternative when only net investment is available is: EBIAT – Periodic change in

8

operating working capital – Periodic change in net investments (after accumulated

depreciation, amortization, and other noncash charges) – Periodic changes in

capitalized operating leases – Investment in Goodwill. Textbook writers usually

simplify the free cash flow items by limiting them to EBIAT + depreciation –

changes in operating working capital – CAPX.

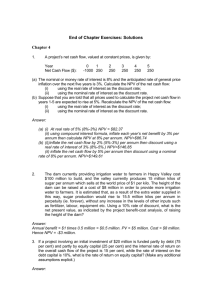

An example calculation of FCF is shown in Table 2, beginning with the

calculations of change in working capital and CAPX.

TABLE 2. CALCULATING FREE CASH FLOW

Time Periods

0

1

2

Operating Cash

25

30

Accounts Receivable

80

90

Inventory

70

80

0

0

Accounts Payable

35

40

Accrued Expenses

45

50

Accrued Taxes

8

10

Other Non-Interest Liabilities

0

0

Current Operating Assets

Other Operating Assets

Current Operating Liabilities

Operating Working Capital

40

87

100

Change in Working Capital

40

47

13

(500)

(100)

(50)

500

600

650

(100)

(225)

500

425

CAPX (Capital Expenditure)

Total Capital Expenditure

Accumulated Depreciation

Net Capital Expenditure

500

9

EBIAT

0

*150

200

*100

125

(40)

(47)

(13)

Minus Change in CAPX

(500)

(100)

(50)

Equals Free Cash Flow

(540)

103

262

Add Back Depreciation

Minus Change in Working Capital

*From Table 1

ALTERNATIVE FREE CASH FLOW CALCULATION

Time Periods

0

1

2

EBIAT

0

*150

200

(40)

(47)

(13)

Minus Change in Net CAPX

(500)

0

75

Equals Free Cash Flow

(540)

103

262

Minus Change in Working Capital

Things to Remember in Calculating FCF

Some of the challenges and important points to remember in forecasting and

evaluating FCF include the following:

1. Separate fixed costs from variable and semi-variable costs if possible.

Variable costs can often be forecast using ratios from past data. Sometimes fixed

costs can be forecast with ratios if you make the assumption that the company is

always working up to capacity.

2. Use iteration (including Solver) to estimate borrowing requirements and

interest costs.

3. Add profit after taxes to retained earnings to get next period’s equity.

Actually, other factors such as gains or losses in the sale of assets (including

10

currency transactions) and dividend payments will affect retained earnings also.

Using the profit to sales ratio to forecast changes in retained earnings seems to be a

common mistake with those new to forecasting.

4. Use only relevant costs and benefits when estimating free cash flow.

Relevant costs and benefits are future costs and benefits that come about only

because an investment opportunity is chosen. Past costs and benefits are sunk—the

money is already spent (benefit received) and cannot be retrieved by choosing one

alternative over another. Those costs and benefits that will occur whether an

alternative is chosen or rejected cannot be relevant to that alternative. Ask yourself:

what changes in the flow of cash will come about if I select this alternative? Those

changes should include opportunities created (opportunity benefits such as options to

invest in other markets that wouldn’t be available otherwise) and opportunities lost

(opportunity costs such as cannibalizing the market share of products already

produced by your company or the opportunity to use existing assets in more

profitable ways than your alternative provides.)

5. Use only changes in working capital and fixed assets. Financial analysts

are interested only in cash inflow and outflow for each period being forecast.

6. Make comparisons among projects only when the discounted costs are

equal among them or the discounted benefits are equal. It is misleading to compare

the return from an investment costing $1 million and returning a NPV of $200,000

with an investment costing $2 million and an NPV of $250,000 unless you know

what the return will be from an additional $1 million spent in conjunction with the

first investment.

7. Avoid consistent bias in the forecast. Behavioral finance teaches that

there are many human factors that may bias a forecast so that it is no longer a true

estimate. Some of these ways include:

A. Risk aversion to a sure loss (taking big risks to avoid a sure loss).

B. Excessive optimism or pessimism.

11

C. Too much or too little confidence in your ability, knowledge,

information, or control over future events and conditions.

D. Confirmation bias: recognizing only events and conditions that

confirm your original assumption.

E. Representativeness: assuming that the average of the past is

representative of the future. This is really important. You use past actual data to

forecast your expected result, and then assume that the expected result is the

required result. In all of this you imply that the market values of the past data

are correct, when, as Franciso de Orsuna (1497–1541) said in the Third Spiritual

Alphabet: "…value reflects only our opinions and not the true worth of the things

themselves." Representativeness stretches credibility, but it may be the only thing

you have unless you can adjust future expectations and requirements using your

experience and common sense and the views of others you respect.

F. Anchoring and adjustment: placing too much emphasis on one

piece of information—an event or statistic (the anchor). You interpret or adjust

other information in light of that event or statistic. An example is using your

company’s overall cost of capital as a basis from which to adjust upward or

downward the risk factor for a project.

G. Over/under reliance on intuition.

THE DISCOUNT RATE

Discounting FCF by the cost of capital or hurdle rate percentage lowers the firm’s

best estimate of an asset’s cash flow to account for four factors that do not appear on

the financial statement of the firm. These factors include the preference investors

have to remain liquid (liquidity preference), inflation, maturity risk, and market risk.

Maturity Risk, Liquidity Preference, and Inflation

12

The financial theory used in practice measures the discount rate as the sum of

a risk-free rate plus a percentage factor for market risk. Analysts usually assume

that the “risk free” rate is the yield of a constant maturity 20-year U. S. Treasury

bond. Twenty years is used because many investments have long lives and the bond

accounts for that fact. However, the bond is not completely risk-free because its

value can vary with changes in the economy. Variations in the bond’s value are

referred to as either investment or maturity risk.

Liquidity preference (often referred to as the real rate of interest) exists for a

number of reasons: the possibility of more attractive opportunities appearing in the

future; the wish to save; or the desire to spend funds now on attractive consumer

items. An investment must promise some return to encourage investors to provide

capital in light of these factors. The required return is relatively low and stable over

time but varies among countries with differing propensities to save.

Inflation reduces the purchasing power of the currency. A dollar today is

worth more than the valid promise of a dollar one year from now because that future

dollar will buy fewer goods and services. Financial managers usually approximate

inflation and liquidity preference by using the U. S. Treasury bill or bond yield as a

risk-free rate.

The two influence one another and therefore cannot be added together along

with maturity risk to obtain the risk free rate of interest. To find the risk free rate of

interest, multiply 1 + the real rate of interest times 1 + the expected inflation rate and

subtract 1. Multiplying the two rates together (simply multiplying fractions), results

in an erroneous number. For example, suppose the real rate of interest is 2% and the

expected inflation rate is 3%. You would expect the combination to be around 5%.

If you multiply .02 * .03, you get .0006 or .06%. If you multiply 1.02 * 1.03 and

subtract 1, you get .0506 or 5.06%. To that, you add the maturity risk.

Companies and investors discount cash flows for maturity risk, liquidity

preference and inflation because money has a time value. If a company must invest

$1 million in the project at the end of time 0, it cannot use the funds for any other

13

purpose. If it may invest instead at the end of year 1, it can purchase a safe U.S.

Treasury security at the beginning of the year and earn “risk-free” interest before

investing. If Treasuries yield 5.5%, the company would need to set aside only

$947,867 in the project at the beginning of year 0, since that amount at interest

would provide the $1 million at the end of the year:

$1 million / (1 + .055) = $947,867

$947,867 + ($947,867 * .055) = $1,000,000

$947,867 X (1 + .055) = $1,000,000

FCF is often forecast on a real or non-inflationary basis. If inflation is not

removed from the discount rate, the FCF will be discounted more than is warranted.

To remove the effect of inflation, divide the risk free rate by 1 + expected inflation.

If the risk free rate is 5.5% and the expected inflation is 3%, divide 1.055 by 1.03

and subtract 1 to obtain 0.0243. The 0.0243 (2.43%) is the rate of interest that

accounts for liquidity preference and the maturity risk. Note that (1+. 0243) * (1 +

.03) minus 1 is equal to 0.055.

Dealing with Risk

Managers generally create a “best estimate” forecast of sales, profits, and

cash flow for operating and capital budgeting purposes. They forecast on the belief

that there will be a 50% chance that the actual numbers will be greater (or less) than

the forecast. Risk is generally defined as the extent of expected variation around the

forecast. The more the variation, the greater is the risk. It is measured by the

variance or standard deviation using data from the past experience of the company or

similar companies, past projects, or by intuition.

Most managers and firms are risk averse. To bet large sums on a coin toss is

considered imprudent. Furthermore, companies operate in an uncertain world where

projects, like tosses of unfair coins, have outcomes impossible to predict with

statistical precision.

Equity Risk

14

The textbooks and industry practice indicate that investors usually develop

percentage factors for discounting using the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) or

similar build-up models. A factor for risk is added to the rate being used as the

measure of future liquidity preference and inflation to “build it up”. It is found by

comparing company returns to the returns of a large number of firms such as those

represented in the Standard and Poor’s (S & P) 500. The S & P 500 firms act as a

proxy variable for risk in the market.

Beta (β) measures the extent to which a firm’s periodic shareholder returns—

dividends and stock splits plus capital gains or losses divided by first-of-period stock

prices—relate to and vary with the average periodic shareholder returns of the

representative market (proxy variable). If a company’s stock varies more than the

average of the proxy, β is greater than one. The firm is riskier than average. A β of

one indicates that the firm is of average risk compared with the proxy; a β of less

than one indicates less than average risk. Beta is multiplied by the risk factor in the

Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and the result is added to the risk free rate to

obtain the cost of equity capital.

The β accounts for systematic risks only—those ups and downs in value

caused by business cycles, interest rates, foreign exchange fluctuations, and sociopolitical changes that are reflected in the proxy. Those factors can affect most or all

firms for good or ill.

Unsystematic risks—risks such as the company’s loss or gain of a major

customer, loss of a key employee or serious competitor, or a boom or bust in the

firm’s industry—are ignored. The idea is that, in general, most investors are well

diversified so that these unsystematic losses encountered by one firm or industry in

their portfolios are offset by unsystematic gains in others. Be careful; it is tempting

to include non-systematic risk factors in the discount rate. Bad practice. It should

be calculated separately when appropriate. Unsystematic risks include country

risks—those special risks associated with doing business in a country outside the

U.S.

15

Consistent negative or positive forecasting bias discussed above is also

ignored and should be dealt with in the FCF rather than the discount rate. To do

otherwise is to violate the assumption that the FCF is a 50-50 estimate and the

discount rate measures only systematic risk.

Entrepreneurs and others whose entire net worth is invested in one or a few

companies are clear exceptions to the rule as they face systematic and unsystematic

risk as well as possible consistent forecasting bias. The message is clear: don’t put

all your eggs in one basket. But sometimes diversification is not possible and a

company specific risk premium (CSRP) should be added to the discount rate.

Finally, smaller companies and companies in riskier industries tend to have

higher capital costs than large companies in stable industries. Additional percentage

points should be added to the discount rate in most firms to account for size.

The Treasury rate plus beta times market risk is the “i” or cost of equity (Ke)

in the PV model above when the firm is financed entirely by common stock. If the

risk free rate is 5.5%, the average return on S&P stocks is 11.5%, and the company’s

beta is 1.2, the “i” or Ke would be 5.5% + 1.2 * (11.5% - 5.5%) or 12.7%. In this

case the equity beta is also called the asset beta. Since there is no debt involved it

measures the total systematic risk associated with the assets. Size and unsystematic

risk factors are added to the “i” to calculate the Ke where appropriate.

Debt Risk

Debt, like equity, can be measured by CAPM. However, debt usually is

measured by its yield to maturity, the internal rate of return (IRR). The price of the

bond is the initial outlay, interest payments represent the FCF, and the principal is

the terminal value. The rate that equates the outlay with the inflow from interest and

principal repayment is the IRR. It is found by iteration, which requires a calculator,

a computer, or a great deal of patience.

16

The value of a debt security will vary over time depending upon market

interest rates. If market interest rates on a similar security change, you substitute the

new interest rate for the old and recalculate the PV. If the new interest rate is higher,

the value of the bond (PV) will decrease; if lower, the value will increase. For

example, if you bought a three year $1,000 bond last year with an interest rate of

4%, and sellers are now offering 5% returns on two year bonds similar to yours, your

bond would be worth [$40 / (1 + .05)] + [($1000 + $40) / (1 + .05)2] = $981.41.

In addition, it is usually the case that the longer the maturity period, the

higher is its interest rate because the risk of default (non-payment) is greater and

because interest rates are more likely to change over a longer time period than a

shorter period. This is why interest rates increase at a geometric rate rather than an

arithmetic rate. However, the yield on short-term bonds may exceed the yield on

long-term bonds if investors think interest rates will drop sufficiently in the more

distant future. Bonds that are not secured by the assets of the firm carry a higher

interest rate because unsecured creditors are paid only after secured creditors in the

event of bankruptcy. Bankruptcy lawyers and consultants, employees, and the

government are paid first; common shareholders are paid last.

Organizations such as Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s (S&P) rate the risk

of bonds using grades. These range from Aaa (Moody’s) and AAA (S&P) to C, with

triple A being the highest. Bonds rated triple B and above are considered investment

grade; those below, as speculative or junk bonds. As a rule, the higher the rating the

lower is the yield. Incidentally, bonds are usually sold in units of $1,000, but are

quoted with the last zero removed. Interest is usually paid bi-annually.

Weighted Average Cost of Capital and Other Adjustments

When debt is used as part of the company’s financing, its cost (Kd) is

included on a weighted average basis. The percentage of debt times its after-tax cost

is added to the percentage of equity times its cost (Ke) to develop a weighted

average cost of capital (WACC). The after tax cost of debt is used because debt,

unlike equity, is tax deductible. Therefore, the actual cost of debt to a company is

17

not what the lender charges, but what the company actually pays after the tax

deduction (1 – T) is taken. The formula is shown as:

i = WACC = [Kd * (1 – T) * %d] + (Ke * %e)

Again, the “1 + i” is compounded to account for the belief that risk grows

geometrically over time rather than arithmetically. For example, period 2’s discount

factor would be (1 + i)2 or (1 + i) * (1 + i). Given a discount rate of 10%, year 2’s

discount factor would be multiplicative (1 + .21) rather than additive (1 + .20).

It is entirely possible that risk associated with expenditures will change at

various times during an investment. An initial investment in research and

development and plant and equipment may occur over a long time period and be

unaffected by systematic risk. In that case, the proper discount rate for the

investment and its depreciation is the riskless rate of interest. If systematic risk is

involved, the riskless rate should be reduced, possibly even to less than one, since

the cash flows involved are outlays. When the project is underway and FCFs are

positive, the discount rate should change to reflect market risk. Finally, the

systematic risk associated with the terminal value may be altogether different and

require another discount rate especially for it.

If risk or inflation is expected to be different in subsequent periods, say .10 for

period one and .15 and .09 for periods two and three, the discount factor for period

two will be (1 + .10) * (1 + .15) = 1.265 and for period three (1 + .10) * (1 + .15) *

(1 + .09) = 1.379.

It is generally assumed that all cash flows occur at the end of the period

being measured, including the cash flow in time period 0. A more realistic

assumption is that cash flows occur in the middle of the year. To account for this,

cash flows are discounted using different powers. If the investment is made at the

end of time period 0 and you are measuring as of that time period, time period one’s

discount would be (1+i)0.5, time period two’s would be (1 + I)1.5, and so on. If the

investment were made at the end of September/beginning of October and cash flows

were assumed to come in the middle of the measured period (mid-November), the

18

first period’s power would be .126 (46/365). In the following year the FCF would

come in the June/July period and the power would be .126 + .5 or .6126. The next

year would be 1.6126, the following year .6126, and so on. It is not possible to use

IRR in these cases because the intervals between periods are not the same and IRR

assumes equal periods. In these cases, use the XNPV and XIRR features of Excel

that are explained at Excel Help.

Since debt is tax deductible and cheaper than equity, financial theory

following Modigliani and Miller (M&M) maintains that the overall cost of capital

tends to drop as tax-deductible debt is added up to the point where bankruptcy risk

becomes an important factor due to overreliance on debt. In the case of debt, interest

and return of capital must occur when due, even when cash is hard to come by. The

alternatives are debt restructuring or default. On the other hand, dividends to

common stockholders may never be paid; dividends to preferred stockholders may

be delayed.

For various kinds of investments made by the firm, many modify their cost of

capital by adding or subtracting percentage points to account for differentials in risk.

This is done subjectively (risking an anchoring and adjustment bias). Alternatively,

financial managers may compare the investment to the cost of capital associated with

pure play companies—companies where 75% or more of the products or services are

comparable to the investment being contemplated. For example, a highly diversified

company that includes a restaurant chain might value the chain using the median or

average cost of capital for companies in the restaurant industry only. Modified costs

of capital derived subjectively or by use of pure play firms are referred to as hurdle

rates or risk adjusted discount rates (RADRs).

There are numerous other methods for evaluating risk. The 5 C’s of Credit

are popular, especially with lenders. Lenders evaluate: Commitment (willingness to

pay interest and principle when due); Capacity (future cash flow available to pay

debts); Collateral (assets available to provide security to the creditor); Conditions

(state of the economy); and Covenants (conditions on the credit such as the

19

minimum level of debt / equity and working capital maintained by the company, and

limits on certain spending without creditor authorization).

Forecasting an optimistic and pessimistic level of sales to test the effects on

profitability is another way to test risk. Scenario analysis, where profits and NPV

are examined assuming different key events and conditions occur or fail to occur, is

related to optimistic/pessimistic forecasting and provides insights into risk.

Evaluating financing risk, market risk, and operating risk is common.

Financing risk (the extent of leverage, or gearing as it is called in the UK) may be

evaluated by the use of debt / equity, debt / total assets, EBIT / interest, and similar

ratios.

Market risk can be examined by estimating the sales level required to reach

profit breakeven (where profit just equals 0). To get that breakeven you divide total

fixed cost (FC) by 1 minus the ratio of variable cost (VC) per unit of output to price

(P) per unit. The denominator (1 – VC per unit / P per unit) equates to the fraction

FC per unit / Price per unit, but is used instead because it is generally easier to

determine the variable costs on a per unit basis. Alternatively, you can divide the FC

by 1 – Variable Costs / Sales. Variable Costs / Sales is defined as the contribution

margin.

The greater the fixed cost (operating risk), the greater the sales must be to

reach profit breakeven. The degree of operating leverage (DOL) is found by the

equations: DOL = % Change in Profits / % Change in Sales. Studies have shown

that companies with high fixed costs (high operating leverage) show relatively large

DOLs, so that a relatively small change in profits requires a relatively large change

in sales.

Firms may also adjust for risk by using certainty equivalents (CEs).

Managers forecast lower but practically certain returns in place of higher but

uncertain best estimate returns. These returns are discounted by the riskless rate of

20

interest to take into account inflation and liquidity preference. Thus, risk is treated

in the numerator instead of the denominator in estimating PV.

A simple mathematical formula may be used to translate a CE free cash flow

into a best estimate, demonstrating that one is directly related to the other. Thus, PV

= CE / (1+i) = BE / (1+k), where PV = present value, CE = certainty equivalent cash

flow, BE equals expected or best estimate cash flow, i = risk free rate, and k =

RADR or cost of capital including risk. If they are not equal in a practical

application, it means that the person who forecasts CE has a different risk propensity

or inflation forecast than the market.

The cost of capital or hurdle rate may be thought of as a way to estimate the

“real” cost of capital (not the same as the “real” rate of interest). However, the real

cost of capital is actually its opportunity cost, the return available from a financial

security such as a stock with a similar risk. You forego the return on that financial

investment if you invest in a project, plant, equipment, or working capital. If your

next best investment opportunity in the financial markets (an opportunity with

similar risks) would earn you 10%, your discount rate should be 10%. You need to

be careful making this comparison because a stock with similar risk traded on an

exchange has almost immediate liquidity, whereas the investment may not be able to

be sold rapidly. As a result, you must apply a discount for lack of liquidity to the

non-financial asset investment.

MORE ON TERMINAL VALUE

PV should include the value of the fixed tangible and intangible assets and

working capital (if any) at the end of the horizon period. That value may be its salvage

value or other market value determined by an estimate of the future selling price of

similar assets (see Market Value above). If there is no depreciation left on the asset—a

piece of equipment or building, for example—the full salvage value is taxed. The tax is

subtracted from the salvage value to determine the TV. If there is depreciation remaining

and it exceeds the selling price, the firm can claim the difference as a capital loss and

deduct the tax rate times the capital loss from the selling price to obtain the TV. If

21

depreciation is less than the selling price, there is a capital gain. The tax rate times the

capital gain is subtracted from the selling price to determine the TV. The capital gains

tax rate is the same as the corporate rate. The lower capital gains rate enjoyed by

individuals is not available to corporations.

Alternatively, the TV may be found by using the perpetuity model: FCF divided

by the discount rate (i). If the FCFs beyond the horizon period are expected to grow at

some constant percentage rate (g), the formula becomes FCF * (1+g) divided by (i – g).

FCF * (1+g) is the FCF that is expected in the next period. The next period is used

because the NPV formula already accounts for the FCF at the end of the horizon period.

As alluded to earlier, his growth formula is sometimes referred to as the Gordon Growth

Model after the person who came up with it. Always remember to discount the TV to the

PV after it is calculated.

OTHER WAYS TO EVALUATE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES

USING

PRESENT VALUE ANALYSIS

Alternatives to PV and NPV include the internal rate of return (IRR), the

modified internal rate of return (MIRR), the profitability index (PI), and the payback

period. It is important to note that different countries exhibit different risk premiums

requiring adjustments in the cost of capital

The most popular alternative to NPV is the internal rate of return (IRR),

discussed earlier. IRR is that percentage discount rate that equates cash outflows with

cash inflows. IRR will always be greater than the discount rate if NPV is positive and

smaller if NPV is negative. IRR will equal the discount rate when NPV = 0. It provides

what many executives see as an estimate of the return on investment in percentage

form—a subjectively preferable way to evaluate return on investment.

There are several downsides to the use of IRR. If the free cash flows are

reinvested at a rate different from the IRR (as is probable), the actual return will be

22

different from the calculated IRR. Also, if there are two or more changes in the cash

flows from plus to minus, there may be two or more IRRs. Selecting the “real” IRR

becomes problematic. Finally, IRR cannot distinguish among the sizes of investment

alternatives. An investment with a high IRR may have a low NPV compared with a

second investment because the first investment and returns involved are very low relative

to the second.

Modified internal rate of return (MIRR) overcomes the first two of the problems

with IRR. MIRR compounds positive cash flows forward to the terminal value at a

reinvestment rate and discounts the total back at the hurdle rate. It is necessary to

forecast a reinvestment rate for the positive cash flows to use this method. Both IRR and

MIRR are available on Excel.

The profitability index (PI) is found by dividing the NPV by the investment

required; alternatively, by dividing the PV by the investment required. If the former is

positive, the investment is financially attractive; if the latter is greater than one, the

investment is financially attractive. The PI indicates which of several projects will give

the highest NPV per dollar spent. As an index, however, it cannot assure that the projects

it compares have equal costs or equal benefits as discussed on page 13 above.

The payback period measures how long in days, months or years it takes to return

the initial investment. The returns may or may not be discounted. The obvious limitation

to this method is that what happens beyond the payback period is not included. Two

opportunities may have a three-year payback (seen to be equal) with one earning $1

million in year four and the other being closed down in year four.

COUNTRY ANALYSIS

Evaluating investment opportunities in different countries requires special

attention to exchange rates, inflation, and country productivity growth—the value over

time of your currency compared with other currencies. Laying aside changes in

productivity, the easiest way to estimate NPV from an investment in another country is to

forecast FCFs in that country’s currency using Country B’s inflation rate. You then

23

discount by a rate that takes into account Country B’s inflation rate compared with

Country A. The formula for this adjustment is:

{[1 + Country A’s discount rate) * (1 + B’s inflation rate)] / (1 + A’s inflation rate)} –

1.00.

You apply this discount rate to cash flows denominated in Country B’s currency to get

PV in Country B’s currency. You then divide Country B’s PV by the exchange rate

(Country B currency / Country A currency) to get PV in Country A’s currency.

THE MARKET METHOD

Fair market value (FMV) as defined by the Internal Revenue Service is:

“The price that property would sell for on the open market. It is the price that would

be agreed on between a hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller,

with neither being required to act, and both having reasonable knowledge of the

relevant facts.”

Usually, the value is the recent price of the item, the current price of

comparable products/services/real estate, the replacement cost, the price determined

by experts, or a current arms-length offer.

Analysts commonly use financial ratios of similar businesses (thus,

businesses with comparable risks) to value the business or company division or other

unit under consideration. These companies are termed “pure play” companies—

ones with 75% or more of their sales in the same industry as the company being

valued. This is valuation by Comparables (“Comps”).

Ratios used for comparison among like companies include:

1. Enterprise value (EV) or market value of invested capital (MVIC), the

sum of all interest bearing debt plus equity either divided by or divided

into:

a.

Net Sales

b. Gross Profit

24

c. EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and

Amortization) or EBITA (without Depreciation)

d. EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes

e. Discretionary Earnings (EBIT + Owner’s Compensation +

Depreciation and Amortization)

f. EBIAT (Earnings Before Interest After Taxes)

2. Common stock price divided by net income per share or price times

number of shares outstanding divided by net income.

3. Common stock value (price * number of shares outstanding) divided by

the book value of the common shares).

4. The above as forecast one or two years out by analysts.

For example, if the enterprise value to EBITDA of the median company in the

industry were 10 and the EBITDA of the business being valued were $500 million,

the business would be valued at $5 billion before relevant adjustments (discussed

below). The stock price to earnings (net income) and market to book ratios may be

used in a similar way to value the equity. Using enterprise value to estimate the

value of equity requires subtracting interest-bearing debt.

[Note: there is lingering controversy over how to find enterprise value since

opinion differs on what current assets and current liabilities to include and exclude.

Do current assets include just inventory? or accounts receivable + inventory but not

cash? or operating cash + accounts receivable + inventory? Do current liabilities

include all current liabilities or just non-interest bearing current liabilities for the

purpose of calculating working capital? We calculate working capital as all

operating current assets (operating—but not excess—cash + accounts receivable +

inventory + other operating current assets if any, minus non-interest bearing current

liabilities. Other assets and liabilities are valued separately.]

A second market method of valuation compares the prices of recent sales

transactions in the industry with the asset to be valued. This is referred to as the

Transaction Method. Ratios are used with this method as well. Also, the assets and

liabilities of recently sold companies are directly compared with the asset being

25

valued. If the assets and liabilities are comparable in a percentage sense, but larger

or smaller in an actual sense, the value of the asset being valued is decreased or

increased proportionately.

When combining comparative data on similar assets, should you use the

mean or the median? The mean is appropriate if there are two or three data points.

For more than three data points, it usually makes sense to use the median if there are

outliers that could bias the result. When ratios are involved, the harmonic mean is

sometimes used so that one large ratio will not unduly influence the outcome. As

mentioned earlier, size affects value—as company size increases, value increases

faster. This calls for adjustment factors. A discussion of these factors is beyond the

scope of this paper.

ADJUSTMENT FACTORS

The price of an asset found by using the asset, market, and income methods

described above should be adjusted by several factors when relevant. Income

statement data should be adjusted to remove or add factors that the buyer finds

reasonable. For example, the CEOs salary may be unrealistically high or low

reflecting the CEO’s best interest. Some new capital expenditures may be required

to keep the company competitive.

In general, the larger the percentage of ownership to be purchased, the lower

is the price per percentage. This corresponds to the idea in economics that the

greater the supply, the lower the price, other things being equal. More than a half

interest in an asset, however, confers the option of control that adds to the price (the

control premium). In the case of companies, larger amounts may confer other

options of value. For example, an 80% interest in a company allows the corporate

holder to transfer profits from the company without paying the relevant federal

corporate income tax. In valuing companies, the percent of the ownership is usually

more relevant than the number of shares owned. A firm may issue as many shares as

it deems appropriate.

26

Ease of resale also adds to the value of an asset. Shares of a public company

can be sold almost immediately and therefore have greater value than the shares of a

privately held firm. Private companies are generally sold at a discount—discount for

lack of marketability (DLOM) or the smaller discount for lack of liquidity (DLOL) if

a controlling interest is to be sold. The smaller the firm, other things equal, the

greater the discount.

Economic theory demonstrates how demand and supply will affect price.

The greater the demand (the “hotter” the firm or industry), the higher is the price.

Speculation will sometimes distort the true value. The state of the economy will also

influence ratios and other data used to value assets. Sometimes these data need to be

normalized to reflect the value of the asset being considered.

In acquiring an interest in a joint venture, division, or company, the new

owners may find themselves with assets such as excess cash, land, plant, and

equipment not directly associated with the purchased asset. They should expect to

pay more for the asset if that is the case. The new owners can sell the unneeded

assets for cash. Alternatively, the new owners may have to add inventory or fixed

assets to support the level of sales used in the valuation. The price should be

reduced in those cases.

Pending lawsuits, potential synergies and other costs and benefits will also

affect the price of some assets. Recent studies have shown that most of the value of

expected synergies in corporate acquisitions goes to the seller.

Finally, the terms of purchase may influence the price. The opportunity to

buy over time may make the asset more valuable to the buyer depending upon the

interest rate charged.