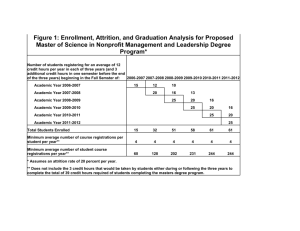

Estimated Year 12 effects on outcomes

advertisement