Granulocytes, electronic 51.0%

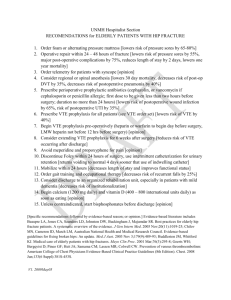

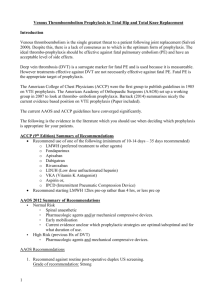

advertisement

Case History and Presentation Suzanne is a 68-year-old woman who is obese and has a history of hypertension that is well controlled with calcium channel blocker therapy. She was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with fever, cough productive of yellow sputum (no blood), and increasing shortness of breath during the past 10 days. For 2 days, she has experienced a sharp pain on the right side of her chest when she takes a deep breath. Walking up stairs has become increasingly difficult due to shortness of breath and fatigue. Suzanne has never smoked and is up to date on cancer screening (negative colonoscopy 2 years ago, normal mammogram 6 months ago, and negative Pap smear 1 year ago). She had no complaints of respiratory distress prior to the past 10 days and reports no weight loss or abdominal discomfort. Suzanne takes a baby aspirin almost every day, which was not recommended by her healthcare provider. Physical Examination • Blood pressure: 130/80 mm Hg • Heart rate: 100 bpm • Temperature: 101.8°F • Body mass index: 28 kg/m2 • Lungs: decreased breath sounds over right mid- and lower-lung field • Abdomen: normal bowel sounds, no tenderness or organomegaly • Heart: tachycardia, regular rhythm, no murmurs • Extremities: trace bilateral ankle edema • Head, eyes, ears, nose, throat (HEENT): dry mucous membranes, otherwise normal • Skin: no rashes or ecchymosis According to the 2008 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Guidelines for VTE Prevention, how should Suzanne’s level of thromboembolism risk be classified? A. Minimal risk B. Low risk C. Moderate risk D. High risk Answer: C Is Suzanne a candidate for anticoagulation therapy for thromboprophylaxis according to the ACCP guidelines? Yes No Need more information to decide Correct answer A Thromboprophylaxis is recommended for patients in the moderate- and highrisk groups. For patients at high risk for bleeding, only early ambulation and mechanical thromboprophylaxis are recommended. Mechanical prophylaxis strategies include graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices, and the venous foot pump. These methods do reduce VTE risk, but have not been studied in randomized trials in medical patients and are not as efficacious as anticoagulant-based prophylaxis Which anticoagulant prescribed for prophylaxis? A. LMWH B. Low dose UFH C. Fondaparinux D. Warfarin should Suzanne’s be VTE Correct. According to guidelines, is LMWH the a recommendation ACCP level 1A (strong recommendation based on randomized trials or exceptionally strong observational data) for VTE prophylaxis in patients at moderate risk. Enoxaparin and or dalteparin high are LMWHs and the only pharmacologic agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for VTE prophylaxis in medically ill patients. In the Prophylaxis in Medical Patients With Enoxaparin (MEDENOX) trial, hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE were randomized to receive subcutaneous enoxaparin 20 mg or 40 mg daily or placebo. A statistically significant risk reduction of 63% for the development of VTE was observed in the enoxaparin 40-mg group versus placebo (Table 3). The incidence of major bleeding events was 1.7% for patients receiving enoxaparin 40 mg compared with 1.1% for those receiving placebo. In the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism (PREVENT) trial, hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE were randomized to dalteparin 5000 IU daily or placebo. A statistically significant risk reduction of 45% for the development of VTE was reported in the dalteparin group. The incidence of major bleeding was low overall, but higher in the dalteparin group (0.49% vs 0.16%). B. Correct. Low-dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) 2 or 3 times daily is an AACP guideline level 1A recommendation for VTE prophylaxis in patients at moderate risk. Three randomized trials of low-dose UFH versus placebo or no prophylaxis showed significant reductions in the incidence of DVT in medical patients. Two of these trials used 3-times-daily dosing and 1 trial used twice-daily dosing. A meta-analysis evaluating 12 trials of twice-daily or 3-times-daily dosing of 5000 IU UFH versus placebo or control drug (N = 7978) showed that 3-times- daily dosing decreased the rate of VTE but increased the rate of bleeding. In a separate meta-analysis, LMWH compared with UFH was associated with a relative risk of 0.68 for the development of VTE. However, the mortality rate did not differ between the groups. UFH remains an efficacious option C. for VTE Correct. The include prophylaxis. ACCP fondaparinux, a guidelines factor Xa inhibitor, as a level 1A recommendation for VTE prophylaxis in the medical patient. In the Idiopathic Ambrisentan in Early Pulmonary Fibrosis (ARTEMIS) trial, a randomized study of fondaparinux versus placebo in hospitalized medical patients, there was a significant risk reduction of 47% in the fondaparinux arm (Table 3). One patient in each group (0.2%) had major bleeding. Eleven patients (2.6%) in the fondaparinux group and 4 (1.0%) in the placebo group had minor bleeding episodes. D. Incorrect. Oral vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are not recommended for VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.They are, however, an option for high-risk patients such as those undergoing major orthopedic surgery and those with major trauma. Case (cont’d) Once-daily subcutaneous LMWH is initiated for VTE prophylaxis. On day 2, Suzanne had 2 episodes of blood-tinged sputum, but this did not recur and she was afebrile by day 4 of hospitalization. Her condition had stabilized enough for discharge from the hospital, but she still had shortness of breath that limited ambulation. The cough had somewhat improved. How long should anticoagulation continue for VTE prophylaxis? A. Stop anticoagulation on discharge B. Continue anticoagulation for 14 days C. Continue anticoagulation for 1 month D. Continue anticoagulation indefinitely Selection Rationale A. Possible. Optimal thromboprophylaxis in duration the of medical patient is not clear. In the MEDENOX trial of enoxaparin versus placebo and the ARTEMIS trial of fondaparinux versus placebo, prophylaxis was given for 6 to 14 days. In the PREVENT trial of dalteparin versus placebo, prophylaxis was given for 14 days. However, these trials do not define the optimal duration of anticoagulation. High-risk general surgery patients, such as those undergoing cancer surgery and those with a history considered of for VTE, may prophylaxis be after discharge for up to 28 days; patients undergoing hip or knee replacement or hip fracture surgery should receive prophylaxis for at least 10 days and up to 35 days. guidelines do However, not recommendations the include for ACCP specific duration anticoagulation in medical patients. of B. Possible. After discharge, medical patients remain at risk for VTE. In a large retrospective study, 37% of 1399 patients who had DVT as outpatients were hospitalized within 3 months before being diagnosed with DVT.20 Half were medical patients who had not had a surgical hospitalization. discharge, procedure Within 67% of 1 during month patients of were diagnosed with DVT and half of those patients were admitted for 4 days or fewer. Although medical patients remain at risk after hospitalization, the optimal duration of VTE prophylaxis is not clear. If bleeding is not a concern, it is reasonable to continue prophylaxis for 14 days; this was the maximum duration in the MEDENOX, ARTEMIS, PREVENT randomized and trials. C. Possible. In the Extended Clinical Prophylaxis Patients in Acutely (EXCLAIM) Ill study, Medical 5105 medical patients with reduced mobility initially were treated with 6 to 14 days of enoxaparin for VTE prophylaxis. After this initial treatment, patients were randomized to receive placebo or to continue days. The enoxaparin for 24 incidence of VTE to 32 was decreased significantly among those given extended prophylaxis versus those given placebo (2.8% vs 4.9%). However, bleeding also was increased in the Because extended Suzanne group has (Table 5). decreased mobility, is obese, and has no excess risk for bleeding, extended prophylaxis may be considered if the risk-benefit ratio is favorable. However, without ongoing severely decreased mobility or another significant VTE risk factor such as a cancer or thrombophilia, most clinicians probably would not give anticoagulation beyond 14 days based on the available data. D. Incorrect. In a patient with only transient risk factors for VTE secondary to hospitalization, indefinite anticoagulation is not a consideration. However, indefinite anticoagulation for secondary VTE prophylaxis may be recommended in some patients after the initial diagnosis of DVT, such as those with cancer, unprovoked DVT, or thrombophilia. Indefinite anticoagulation also may be considered for patients in long-term care facilities who have decreased mobility. Case Conclusion Suzanne was discharged home on oral antibiotics and prescribed LMWH for 14 days, including the days she received it in the hospital. Before discharge, she was taught how to administer subcutaneous medication. She also was directed to look for and report immediately any signs of bleeding such as blood in the sputum or spontaneous bruising. She was not to resume taking aspirin until she discussed it with her primary care provider at the 2-week follow-up postdischarge. She had no bleeding and was largely asymptomatic at the follow-up visit except for lingering fatigue. Chief Complaint “I’m having pain in my leg.” HPI Robert Roberts is a 54-year-old man who presented to his primary care physician because of pain in his right leg. He states that he awoke with the pain 3 days ago and that it has been continuous, although it hurts more when he walks. The patient denies chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, headache, and leg trauma. The patient started ezetimibe 10 mg daily for treatment of hyperlipidemia approximately 3 weeks prior to this visit. He stopped the ezetimibe 3 days ago because he thought it might be causing his leg pain, but the pain has continued. Physical examination reveals a tight, warm, right calf with mild tenderness. Lower extremity pulses and sensation are normal bilaterally. The physician’s differential diagnosis includes deep vein thrombosis and rhabdomyolysis, and the patient is referred to the emergency department for further evaluation. The emergency department history includes persistent pain in the right calf that is exacerbated by walking, with no remitting factors. The patient rates the pain intensity as 3/10 at this time. PMH Graves’ disease with thyroid ablation Gout Hyperlipidemia Left ankle fracture 9 years ago that required a cast but no surgery Remote history of depression PSH Left herniorrhaphy about 10 years ago Pilonidal cyst excision in remote past FH Father died at age 81 of liver failure. Mother, one brother, and son all alive and well. No family history of venous thromboembolism or clotting disorders. SH Married, one adult child. Drinks one to two alcoholic beverages daily. Smokes one cigar per month, no cigarettes. Denies illicit drug use. Meds Allopurinol 300 mg po daily Levothyroxine 150 mcg po daily Ezetimibe 10 mg po daily (discontinued 3 days ago) All NKDA ROS Constitutional: No chills, no fatigue Eyes: No eye pain or changes in vision ENT: No sore throat Skin: No pigmentation changes, no nail changes Cardiovascular: No chest pain, palpitations, or syncope Respiratory: No cough, SOB, wheezing, or stridor GI: No abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, or vomiting Musculoskeletal: No neck pain, back pain, or injury Neurologic: No dizziness, headache, or focal weakness Psychiatric/Behavioral: No depression Physical Examination Gen Somewhat obese, Caucasian man who appears comfortable. Cooperative, A & O •~ 3, normal affect. VS BP 106/78, P 75 regular, R 16, T 98.3•‹F, O2 sat 97/ra; Wt 245 lb, Ht 6'0'' Skin Warm, dry, normal color. No rash or induration. HEENT Pupils equal and reactive to light. EOM intact. Mucous membranes moist and pink. Neck Normal range of motion with no meningeal signs Lungs/Thorax Breath sounds normal, no respiratory distress CV RRR, no rubs, murmurs, or gallops Abd Non tender, no masses, no distension, no peritoneal signs MS/Ext Upper extremities: normal by inspection, no CCE, normal ROM. Lower extremities: no CCE, normal ROM. Right calf tender with mild swelling. No obvious compartment syndrome. Neuro Glasgow coma scale of 15, no focal motor deficits, no focal sensory deficits Labs Lower extremity venous duplex ultrasonography: acute DVT of right distal superficial femoral, popliteal, and peroneal veins. No compression or flow in these vessels. Assessment Acute DVT in right superficial femoral, popliteal, and peroneal veins Na 140 mEq/L WBC 5.9 •~ 103/ƒÊL K 3.9 mEq/L RBC 4.28 •~ 106/ƒÊL Cl 103 mEq/L Hgb 13.5 g/dL CO2 27 mEq/L Hct 39.3% BUN 10 mg/dL MCV 92.0 fL SCr 0.84 mg/dL MCHC 34.4 g/dL Glucose 88 mg/dL RBC dist 14.3 Uric acid 5.0 mg/dL Platelets 118 •~ 103/ƒÊL CK 117 U/L Mean platelet volume 7.2 fL Granulocytes, electronic 51.0% Lymphocytes, electronic 38.2% Monocytes, electronic 8.4% Eosinophils, electronic 1.9% Basophils, electronic 0.5% ESR, Westergren 9 mm/h Lower extremity venous duplex ultrasonography: acute DVT of right distal superficial femoral, popliteal, and peroneal veins. No compression or flow in these vessels. Follow-Up Question 1. Identify the patient•fs anticoagulation therapy-related drug therapy problem(s) and design treatment and monitoring plans for managing each problem you identify. CLINICAL COURSE Mr. Roberts presents to his primary care physician•fs office approximately 3 months after his acute DVT episode. He reports that he experienced an episode of very dark brown, •gcola•h-colored urine 2 days before this visit. He has had no recurrences. The patient denies dysuria, back or groin pain, and blood in his bowel movements. His current dose of warfarin is 5 mg on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday and 7.5 mg on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday. Physical examination reveals no CVA tenderness. Follow-Up Question 1. Identify the patient•fs anticoagulation therapy-related drug therapy problem(s) and design treatment and monitoring plans for managing each problem you identify. CLINICAL COURSE Five months after his initial presentation, you see Mr. Roberts in the new anticoagulation clinic at his primary care physician’s office. He is currently taking warfarin 5 mg on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday and 7.5 mg on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday. His INR is 3.3. The patient’s INR 2 weeks ago was 2.1 on the same dose. Mr. Roberts has not experienced any symptoms suggesting DVT recurrence or PE occurrence. He states that he has not had any problem with bleeding, has not missed doses or taken extra doses of warfarin in the past month, and has not changed his diet. His medications have been unchanged, except for the addition of rosuvastatin 5 mg every other day for the treatment hyperlipidemia approximately 2–3 of his weeks ago. You note that the following thrombophilia tests were completed prior to the initiation of anticoagulation therapy: The laboratory summarizes the above results as consistent with the presence of lupus anticoagulants. Even though “anticoagulants” are present, many patients with this condition experience thrombotic events. “My chest hurts and I feel like I can’t get enough air.” HPI Michael Veder is a 52-year-old man who was transferred to the hospital’s skilled nursing unit to complete IV antibiotic therapy for a gangrenous chronic wound infection on his left ankle secondary to poorly controlled diabetes. The patient is S/P BKA left leg (postop day #11) and has completed 11/14 days of the IV antibiotic regimen. He has tolerated the antibiotics well and his pain is improving daily, although he often refuses physical therapy in the skilled nursing unit. Early this morning, the patient complained of sharp chest pain and shortness of breath. The pain does not radiate. He denies nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. The patient is anxious. He has a non-productive cough and he claims that he has been having trouble with deep inspiration since yesterday. PMH HTN × 12 years Type 2 DM × 10 years; uncontrolled due to noncompliance with diet and medications at home Diabetic nephropathy (baseline creatinine 1.4 mg/dL) Obesity Chronic wound infection left ankle (previously failed 2 courses of IV antibiotics) S/P BKA left leg (post-op day #11) FH Father has Type 2 DM SH The patient performs with a local rock band and leads an unhealthy lifestyle (poor diet, no exercise). Significant for tobacco abuse (20 pack-year history). Denies illicit drug use. Drinks alcohol socially on the weekends. Meds Home medications: Novolin 70/30 40 units Q AM and 30 units Q PM Lisinopril 10 mg po once daily Additional medications started in the skilled nursing unit: Unfractionated heparin 5,000 units subcutaneously every 8 hours Nicotine transdermal patch 21 mg/day Cefepime 2 g IV every 24 hours Vancomycin 2 g IV every 24 hours Meperidine 50 mg po every 4–6 hours PRN pain Metformin 500 mg po twice daily Regular insulin sliding scale subcutaneous coverage AC and HS: Glucose 150 to 199 mg/dL—2 units Glucose 200 to 249 mg/dL—4 units Glucose 250 to 299 mg/dL—6 units Glucose 300 to 349 mg/dL—8 units Glucose greater than or equal to 350 mg/dL—call physician for orders All NKDA ROS The patient denies headache, fever, chills. Positive for shortness of breath, nonproductive cough. Positive for chest pain. No palpitations. No abdominal pain. No nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Physical Examination Gen The patient is alert and oriented × 3; moderate respiratory distress VS BP 132/66, P 88, RR 21, T 36.5°C; Wt 102 kg, Ht 5'10'', O2 sat 96% on room air Skin Warm and dry HEENT Head: Atraumatic; PERRLA; EOMI Neck/Lymph Nodes No carotid bruits; no lymphadenopathy Lungs/Thorax Clear to auscultation bilaterally; wheezing or crackles no CV RRR; normal heart sounds; no murmurs, rubs, or gallops Abd Soft; NT/ND; good bowel sounds Genit/Rect Patient refused at this time MS/Ext S/P BKA left leg; range of motion within normal limits; no swelling or redness; no cyanosis Neuro No focal deficits noted; cranial nerves intact ECG Normal sinus rhythm at 88 bpm. No Q waves or ST changes present. No ectopy. Normal QRS axis, normal QRS morphology. Assessment 1. Chest pain, SOB—most likely noncardiac, R/O PE, R/O pneumonia 2. Thrombocytopenia—R/O heparininduced thrombocytopenia (HIT) 3. Chronic wound infection, S/P BKA— continue current antibiotic regimen to complete 14 days, continue wound care and pain management 4. Diabetes mellitus—blood glucose well controlled on current medications and hospital no-added sugar diet 5. HTN—stable on current regimen Clinical Course The patient was transferred to a monitored unit within the hospital for further work-up. A chest x-ray and spiral CT of the chest were ordered. The spiral CT was later canceled due to the patient’s elevated creatinine and the risk of contrast nephropathy. A V/Q scan was ordered. A platelet count history was obtained from the skilled nursing unit. QUESTIONS Problem Identification 1.a. What subjective and objective information is consistent with a diagnosis of PE in this patient? 1.b. What risk factors for PE are present for this patient? 1.c. Calculate this patient’s pre-test probability score for HIT 1.d. Develop a list of the potential drug therapy problems related to this patient’s increased serum creatinine. Desired Outcome 2.a. What are the goals of therapy for the treatment of PE? 2.b. What additional goals of therapy exist for this patient with HIT? Therapeutic Alternatives 3.a. Which agents are available to initiate anticoagulation for the treatment of PE in this patient? 3.b. What non-anticoagulant alternatives (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) are available? Is this patient an appropriate candidate for any of these alternatives? Optimal Plan 4.a. Choose an appropriate anticoagulant to initiate therapy and calculate the dose for this patient. 4.b. When can warfarin be started for longterm management of PE in this patient? Design a pharmacotherapeutic plan for the transition to warfarin. ■ CLINICAL COURSE The patient was started on an IV infusion of lepirudin at 10:00 AM. A heparin-induced platelet antibody ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) was drawn and sent to an outside laboratory for confirmation of HIT. An order was written to avoid all heparin (including catheter flushes). Prior to initiating lepirudin, a baseline aPTT (27.3 sec; reference: 23.8–34.6 sec), PT (11.1 sec; reference: 9.8–12.3 sec), and INR (1.0) were obtained to assist with anticoagulation dosing. Outcome Evaluation 5.a. Determine the therapeutic aPTT range for the direct thrombin inhibitor administered to this patient. 5.c. What clinical and laboratory parameters will you use to monitor the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation in this patient? Patient Education 6.a. Prior to discharge, what information should be provided to this patient about warfarin therapy to enhance compliance and ensure efficacy and safety? 6.b. Discuss the information that you will provide to this patient concerning the future use of heparin and low molecular weight heparin therapy. ■ SELF-STUDY ASSIGNMENTS 1. Compare the risk of the development of HIT with unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin. List other risk factors that influence the development of HIT. 2. Investigate the sensitivity and specificity of the various activation and antigen assays available to confirm the diagnosis of HIT. 3. Considering the potential for combined effects on the INR, list the steps necessary to transition a patient receiving argatroban to warfarin therapy. Review the literature for available options to reverse the effects of the direct thrombin inhibitors if excessive anticoagulation occurs. CLINICAL PEARL Heparin-associated thrombocytopenia (HIT Type 1), which is more common than heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT Type 2), is a nonimmunogenic mild decrease in platelet count (nadir greater than 100 × 103/mm3) that occurs within 1 to 3 days after the initiation of heparin and does not increase the patient’s risk of thrombosis or require heparin discontinuation.