DVT-PE Toolkit Update

advertisement

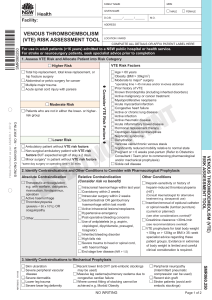

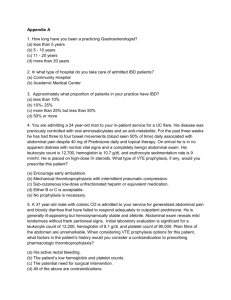

A Note about DVT-PE Protocols from Dr. Greg Maynard All, A lot has changed since that implementation guide was built. I am currently in the process of an extensive update / revision. I’ve pasted in a portion from the preface that describes the purpose of the guide, and what to expect in the new version that will be coming out this summer. I also attached an Appendix that will be incorporated. I thought they might help get the conversation going, if you want to distribute to others. GM Purpose of this Guide In 2008, AHRQ, in conjunction with the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), published “Preventing Hospital-Acquired Venous Thromboembolism: A Guide for Effective Quality Improvement” authored by Dr. Jason Stein and I.36 The original guide (and the sister publication by SHM)37 was based on our local success in VTE protocol design and implementation38-40 and quality improvement principles. The purpose of those publications and this extensive update and revision, is to assist hospital improvement teams to close this implementation gap as effectively and efficiently as possible. While guidelines often focus on defining best practice, this work has a focus on the specifics of how to insure those best practices get reliably delivered in your local inpatient environment. There are multiple barriers and “failure modes” that must be overcome to reliably provide prophylaxis to those at risk, while avoiding over-prophylaxis of those that aren’t. It turns out that VTE prophylaxis is a somewhat complex process in a very complex system of the hospital environment. As systems, hospitals are perfectly designed to achieve the results they attain, and improving care generally involves changing the basic design of elements of that system, and careful monitoring to adjust the interventions and insure that the change leads to the desired improvement. The basic principles and essential elements to reach breakthrough levels of improvement in care have not changed since we listed these items in the first edition: Institutional support and prioritization for the initiative, expressed in terms of a meaningful investment in time, equipment, personnel, and informatics, and a sharing of institutional improvement experience and resources to support any project needs. A multidisciplinary team or steering committee focused on reaching VTE prophylaxis targets and reporting to key medical staff committees. Reliable data collection and performance tracking. Specific goals or aims that are ambitious, time-defined, and measurable. A proven QI framework to coordinate steps towards breakthrough improvement. Protocols that standardize VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis. Institutional infrastructure, policies, practices, or educational programs that promote use of the protocol. The protocol that standardizes VTE risk assessment is so fundamental that it must not merely exist. It must be embedded in patient care. High-reliability design should be used to enhance effective implementation. Thus, some sections in this revision may seem quite familiar, and will be quite similar to the first version. What’s New – Rationale for an update to this guide On the other hand, this revision will incorporate a large number of additions and changes to reflect important changes in the environment, new guidelines, and lessons learned. More specifically, this version will be enhanced by reflecting: 1. Lessons from collaboratives and success stories: The first edition of this guide was used as the centerpiece of a number of multi-site collaborative improvement efforts by the AHRQ (in conjunction with Quality Improvement Organizations, most notably JENY IPRO), the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), and the SHM Eisenberg Award winning “Mentored Implementation” programs. This experience in a wide variety of hospitals has provided insight into what works, and perhaps just as importantly, what doesn’t work in real world settings.41,42 Many others have also published outlines of “what works” and what didn’t work in their setting, and I have attempted to collate some of those strategies that may have portability across a variety of settings.43-62 2. Context of new evidence and new guidelines from the American College of Physicians (ACP), the 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians on Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis (AT-9), and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS): The ACP Guideline (ACP-1)17 and supporting review63 addressed VTE prophylaxis (VTEP) in nonsurgical patients, while AT-9 guidelines7 cover a wide variety of patient populations in separate guidelines for medical inpatients,18 orthopedic patients,20 and non-orthopedic surgical patients.19 Both ACP-1 and AT-9 differ significantly from the 2008 ACCP guidelines (AT-8),15 placing more emphasis on the dangers of over-prophylaxis of patients at low risk of VTE, and making several changes in guidance. They also took different approaches to methodology, risk-assessment, and several other aspects of VTEP. Complicating matters further, AAOS guidelines23 and others21,22 are not always consistent with AT9 guidelines. The complexity of the new guidelines, lack of consensus about VTE risk-assessment, varied estimates of risk and benefit, and significant changes from AT-8 have contributed to uncertainty about best practices in VTE prevention and design for VTE prevention protocols. Therefore, in this update, we review and critique these guidelines in much more detail, update recommendations for order sets and protocols to reflect the guidelines, while still staying true to the principles of effective clinical decision support. 3. Increased Use of Electronic Medical Records (EMR), computerized physician order entry (CPOE), and advanced information technology: More examples of tools in this new environment will be featured, as we explore the “good, the bad, and the ugly” aspects of implementing protocols in the emerging computerized medical environment. Tools to illustrate Clinical Decision Support in CPOE / EMR formats, which go above and beyond Health and Human Services (HHS) Meaningful Use Criteria for VTEP will be presented. 4. New measures: New and improved metrics for tracking the adequacy of VTEP, including information on using measurement with concurrent intervention (aka measure-vention) will be extensively reviewed. New ICD-9 codes for HA-VTE have been released since the last version of this guide was published. Guidance that outlines optimal utilization of administrative data to track HA-VTE will be updated to include the Present on Admission (POA) indicator, and to capture patients readmitted with new VTE within 30 days of a prior hospital stay. 5. New methods to improve on reliable delivery and enhanced adherence to VTE prophylaxis orders (as opposed to focusing solely on getting the order correct): This is important in view of commonly reported deficiencies in adhering to mechanical VTE prophylaxis (50-60%) and pharmacologic prophylaxis (10-20% of doses commonly not delivered). 6. Consolidation of information from several government agencies: This includes AHRQ Patient Safety Organization Common Formats for reporting on VTE, Center for Disease Control, and CMMS regarding VTE Prevention. 7. New information focusing on the importance of patient engagement and education, transitions of care, indications for extended duration prophylaxis, and prophylaxis in special populations (eg: obesity, renal failure, liver disease, the elderly, patients going to skilled nursing facilities or rehab facilities). 8. Addition of FAQs for VTE Prevention, and a concise Executive Summary.