Reconsidering Britain`s first urban communities Martin Pitts

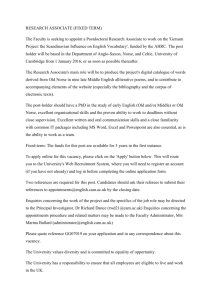

advertisement