Arts of the Contact Zone – Ashley Lazorchak

advertisement

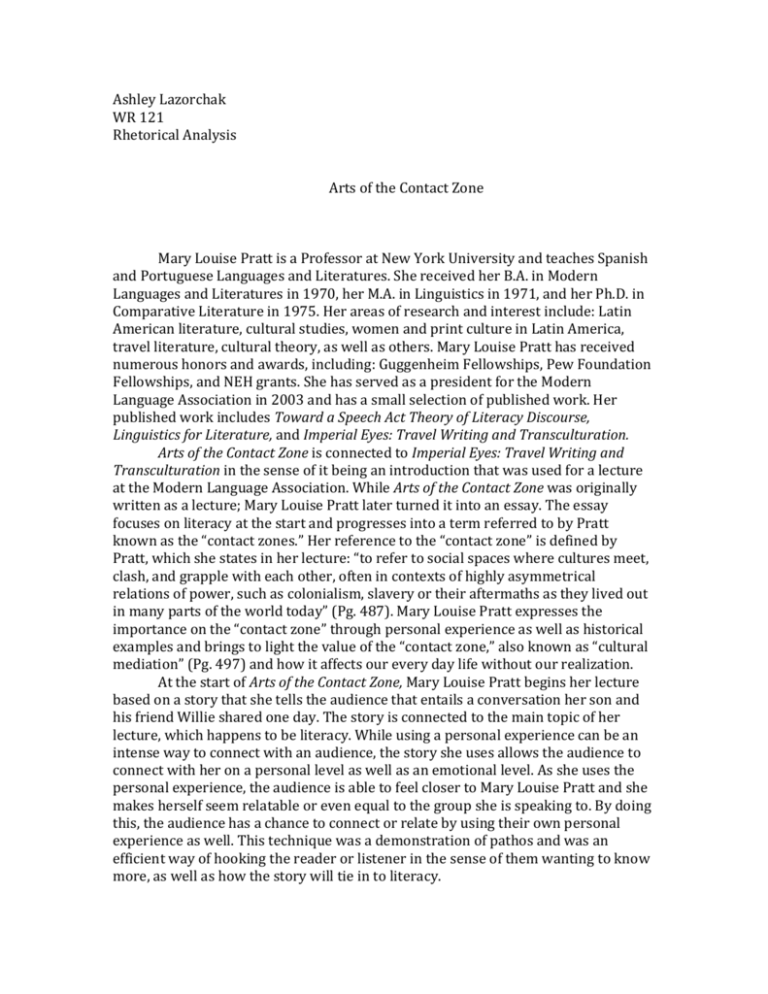

Ashley Lazorchak WR 121 Rhetorical Analysis Arts of the Contact Zone Mary Louise Pratt is a Professor at New York University and teaches Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Literatures. She received her B.A. in Modern Languages and Literatures in 1970, her M.A. in Linguistics in 1971, and her Ph.D. in Comparative Literature in 1975. Her areas of research and interest include: Latin American literature, cultural studies, women and print culture in Latin America, travel literature, cultural theory, as well as others. Mary Louise Pratt has received numerous honors and awards, including: Guggenheim Fellowships, Pew Foundation Fellowships, and NEH grants. She has served as a president for the Modern Language Association in 2003 and has a small selection of published work. Her published work includes Toward a Speech Act Theory of Literacy Discourse, Linguistics for Literature, and Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. Arts of the Contact Zone is connected to Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation in the sense of it being an introduction that was used for a lecture at the Modern Language Association. While Arts of the Contact Zone was originally written as a lecture; Mary Louise Pratt later turned it into an essay. The essay focuses on literacy at the start and progresses into a term referred to by Pratt known as the “contact zones.” Her reference to the “contact zone” is defined by Pratt, which she states in her lecture: “to refer to social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery or their aftermaths as they lived out in many parts of the world today” (Pg. 487). Mary Louise Pratt expresses the importance on the “contact zone” through personal experience as well as historical examples and brings to light the value of the “contact zone,” also known as “cultural mediation” (Pg. 497) and how it affects our every day life without our realization. At the start of Arts of the Contact Zone, Mary Louise Pratt begins her lecture based on a story that she tells the audience that entails a conversation her son and his friend Willie shared one day. The story is connected to the main topic of her lecture, which happens to be literacy. While using a personal experience can be an intense way to connect with an audience, the story she uses allows the audience to connect with her on a personal level as well as an emotional level. As she uses the personal experience, the audience is able to feel closer to Mary Louise Pratt and she makes herself seem relatable or even equal to the group she is speaking to. By doing this, the audience has a chance to connect or relate by using their own personal experience as well. This technique was a demonstration of pathos and was an efficient way of hooking the reader or listener in the sense of them wanting to know more, as well as how the story will tie in to literacy. The story focuses on her young adolescent son Sam and his love for baseball cards. She uses this example as a way of showing her son and his friend Willie using the limited literacy skills they have learned so far. Through his passion of baseball cards, her son learned many things about life such as “exchange, fairness, trust, the importance of processes as opposed to results, what it means to get cheated, taken advantage of, even robbed” (Pg. 485) as well as “the history of American racism and the struggle against it through baseball; he saw the Depression and two world wars from behind home plate. He learned the meaning of commodified labor, what it means for one’s body and talents to be owned and dispense by another. [...] Through the history and experience of baseball stadiums he thought about architecture, light, wind, topography, meteorology, the dynamics of public space” (Pg. 485). The examples Pratt includes in her story about her son shows that his literacy evolved from his desire to learn more about baseball cards and that literacy is a part of every day life and is significant to pursuing things we enjoy. As her son expanded his knowledge from literacy, he was able to gain knowledge in many other things. While this was positive to Pratt, she states in her lecture that she “was delighted to see the schooling give Sam the tools with which to find and open all these doors. At the same time I found it unforgiveable that schooling itself gave him nothing remotely as meaningful to do” (Pg. 486). With this statement, Pratt introduces her purpose of the lecture, which is based on the fact that she believes multicultural learning in schools is not significant enough. As Pratt finishes the story regarding her son, she eases into another example, which happens to be a historical story and continues by laying down the foundation for the discussion of literacy between cultures. Mary Louise Pratt begins her historical story by telling the audience about the manuscript found in Copenhagen that was written by an Andean man named Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala. It is written in Quechua as well as “ungrammatical and expressive” Spanish and was a letter addressed by an Andean to King Phillip III who resided in Spain. The manuscript had never been read from a society that was considered to be literate and consisted of twelve hundred pages long. It was titled The First New Chronicle and Good Government and included eight hundred pages of written text while the remaining four hundred pages included “captioned line” drawings. While the letter was substantial, it took an abundance of years to bring light to the manuscript that Guaman Poma wrote and many more years after that for it to be interpreted and appreciated for what it really was. By Pratt using this story, she allowed the audience to see that people were slow to appreciate how powerful literacy is and the importance of something such as a manuscript written by an Andean man. This historical story Pratt uses not only gives way to her upcoming topic concerning the “contact zone,” but also allows Pratt to continue to establish relationships with the academic audience, such as professors, instructors, students or even historians. Throughout Pratt’s historical example, she introduces the term the “contact zone” and continues to define what it is. As her historical story progresses, it is clear that Guaman Poma’s manuscript is an impeccable example of the “contact zone,” and as Pratt states in her lecture: “In sum, Guman Poma’s text is truly a product of the contact zone. If one thinks of cultures, or literatures as discrete, coherently structured, monolingual edifices, Guaman Poma’s text, and indeed any autoethnographic work, appears anomalous or chaotic…” (Pg. 492). It shows the audience that everyone will decipher the letter differently, based on their position within the contact zone. As Pratt wraps up her historical example, she connects the “contact zone” with literacy and includes some of the “literate arts of the contact zone” such as “autoethnography, transculturation, critique, collaboration, bilingualism, mediation, parody, denunciation, imaginary dialogue, vernacular expression” (Pg. 492). While she includes the positive aspects to the “contact zone,” Pratt also includes the negative aspects to the “contact zone” which include “miscomprehension, incomprehension, dead letters, unread masterpieces, absolute heterogeneity of meaning” (Pg. 492). By showing the pros and cons to the “contact zone,” Pratt allows the audience to see how these relate to present day. Continuing on the topic of the “contact zone,” Mary Louise Pratt begins her next section by explaining how “contact zones” compare with the concept of community that takes place in the academic field. “The idea of the contact zone is intended in part to contrast with ideas of community that underlie much of the thinking about language, communication, and culture that gets done in the academy” (Pg. 493). She uses an author and professor by the name of Benedict Anderson in this section and explains Anderson’s ideas about “imagined communities” (Pg. 493), which is based on a book he has written. As she exposes Anderson’s ideas as well as her own, she uses his name and examples as a credibility source in her lecture. It allows the audience to see that she is knowledgeable in what she is sharing with them as well as explaining that everyone in our society is different, leaving no one the same as the other. No two individuals have the same writing or the same way of communicating, therefore making every connection that you have a “contact zone.” While Mary Louise Pratt’s lecture and essay Arts of the Contact Zone could be considered a “difficult” read or listen to some, her main point and argument of her lecture was represented in a clear and efficient way. She expressed her opinions and beliefs in a skillful manner by ensuring that she connected to her audience or reader. By using personal experiences, such as a lighthearted story about her son, she was able to connect to her audience on a personal level as well as an academic level by using Guaman Poma’s story as well. The audience could hold many of the values Pratt does, such as: family, literacy or overall academic studies. She gives many examples and arguments as to why multicultural education will not only broaden, but also ensures a better learning experience to students in their academic studies.