- Sierra Club

advertisement

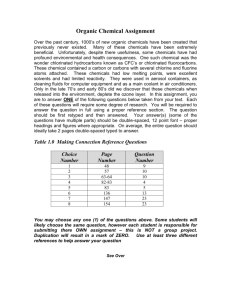

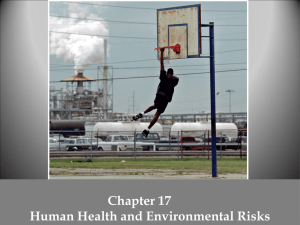

Section I: Introduction Purpose of this Handbook How this Handbook was produced Selecting Case Studies Summary of Key Lessons Percy, a member of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade is taking an air sample near a polluting factory. Section II: About Community Monitoring Why community monitoring? What is community monitoring? Health effects of selected chemicals An Interview with Dr. David Carpenter Section III: Community Monitoring Case Studies Alaska Community Action on Toxics (ACAT), St. Lawrence Island Community against Pollution (CAP) of Anniston, Alabama, PCB Contamination from Monsanto Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) Bucket Brigades, Contra Costa County, California Pesticide Exposure and Childhood Development in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico Phthalates: Body Burden and Product Testing San Diego Environmental Health Coalition Health Surveys in San Diego Communities State University of New York and the Akwesasne Community, PCBs in Breast Milk in the Akwesasne Mohawk West Oakland Neighborhood Groups and The Pacific Institute, West Oakland Indicators Project Appendix A: Survey Purpose of this Handbook This handbook is intended as a resource for communities interested in conducting or already engaged in monitoring projects. The handbook showcases the energy and ingenuity displayed by community groups across the country incorporating monitoring into their campaigns. The handbook is designed to help communities determine which monitoring method is best for a particular campaign, and where to find more information. By explaining how various types of monitoring have been effectively used to support a range of campaigns and community-based efforts, the handbook will help other communities build on these experiences and choose the right monitoring tools. How this Handbook was produced This handbook was produced through the generous support of Coming Clean. Coming Clean is a network of groups and individuals whose common goal is to work together on chemical policies and campaigns to protect public health and the environmental from exposures to harmful and unstudied chemicals. Information about Coming Clean can be found on the web at (http://www.comeclean.org/homecc.htm). Coming Clean serves as an incubator for these campaigns and strategies. Coming Clean was formed in early January 2001 to take advantage of the tremendous public education opportunity provided by the PBS broadcast of Trade Secrets: A Moyers Report. Bill Moyers' groundbreaking 90 minute documentary reported on how the chemical industry has produced thousands of man-made chemicals that have not been tested for their effect on the public's health and safety. The campaign involved reaching out to and assisting health and environmental groups around the country to organize events around the Trade Secrets broadcast. The campaign's efforts led to over 120 public viewing events and more than 650 news articles around the country on Trade Secrets and associated local activities. Trade Secrets provided a tremendous opportunity to focus national attention on the chemical industry and the myriad ways that it works to keep its products on the market and safe from public scrutiny of possible health effects. Why Community Monitoring? Communities across the United States and around the world are documenting chemicals and their impacts on the health and environment of the community. This community monitoring, which is often done in the context of specific local campaigns, can be time and resource intensive. Why go to this trouble? An ominous combination: a playground with a chemical or petroleum facility in the background in Norco, Louisiana Unfortunately, millions of people in this country and hundreds of millions around the world live in environments severely damaged by historical and ongoing contamination of the soil, air, and water. These contaminants adversely impact our health and accumulate in our bodies, homes and workplaces, shortening the lives of community members, and impairing childrenâs health and development. Many products sold in our stores pose a substantial risk to those who use them, and there are inadequate safeguards to protect consumers. There are literally thousands of lakes and rivers where the fish are not safe to eat, and even fish caught in the open ocean are contaminated by the deposition of pollutants like mercury transported long distances from their source. In the face of these problems, communities have refused to remain passive and wait for outsiders to assess and fix the problems. They demand change and have mobilized to collect the information necessary to convince decision-makers, manufacturers, and the courts that change must occur now. What is Community Monitoring? Community monitoring is a locally-based process of documenting chemicals or their effects in a given community. There are a variety of approaches to monitoring, each with strengths and weaknesses that need to be assessed by community members considering a monitoring project. This handbook presents case studies representing six types of community monitoring, with some projects including elements of more than one type. The six types of monitoring are: Monitoring Chemicals in the Environment - Direct measurement of releases or ambient of concentrations of chemicals or pollutants in the environment. Monitoring Chemicals Contained in Products or Food - Documentation of known or suspected toxic chemical substances contained in commercial products or of hazards associated with the use of commercial products. Monitoring Body Burden - Measurement of chemicals or pollutants in people's bodies. Monitoring Human Health - Measurement of human health indicators or patterns of disease. Monitoring Regulatory Performance - Monitoring the performance of both public and private organizations responsible for enforcing regulation designed to protect health or the environment. Monitoring Ecological/Biological Health and Effects - Documenting the impacts of chemical pollutants on living organisms. Monitoring of Hazardous Incidents - An acutely hazardous incident poses an immediate threat to human or ecological health. Selecting Case Studies Working with partner groups around the country, we identified several examples of the six types of community monitoring described above. In selecting case studies, we attempted to geographically cover the United States and demonstrate the diversity of methods employed. Only a few of the hundreds of effective community projects are profiled here. We primarily feature projects that are designed and driven by local communities. A few of the highlighted projects have a low level of community involvement, but were included because they employ unique or interesting methods that may be useful to other communities. After gathering readily available information about each project, we interviewed contacts to collect additional and more in-depth information. We attempted to collect the same information for each case study, using the survey in Appendix A. Each case study is presented in a similar format to make it easier to compare and contrast different cases. Each case study begins with a brief overview of the project to help guide the reader to areas of most interest. Summary of Key Lessons Monitoring tools employed in the case studies range from fairly simple and low-cost methods to those that are expensive or require a significant investment in training and capacity-building. Creating community maps illustrating the scope and patterns of health problems in a community is a low-cost tool that doesnât require much training. It is also relatively inexpensive to administer a community health survey to provide data for a mapping project, but this can be very time consuming and may require training as survey and questionnaire design can be a complicated task. Other tools, such as monitoring toxins in breast milk, are both expensive and highly technical, and require either contracting or partnering with a scientific laboratory. Collecting environmental samples with simple tools such as those used by the "bucket brigades" does not require much technical training or expertise, but does depend on highly effective community organizing and coordination. Some of the monitoring methods discussed in this book are so powerful that they require additional consideration and sensitivity. Testing humans for toxic chemicals (in blood, urine, breastmilk, etc.) can provide the ultimate proof of chemical exposure, and can be an extremely valuable tool for a community to use. However, knowing one's own chemical body burden can be an emotionally experience. Some participants in such monitoring studies have felt disempowered or deeply disturbed when they learn about their own chemical body burden, especially when that part of their body burden made up of those chemicals known to take up long term residence in the fatty substances in oneâs body, because there is very little known about how to remove such chemicals. Counseling before and after testing helps participants cope with the knowledge of these chemicals in their bodies. Confidentiality in such cases is also important to avoid the results influencing health insurance of participants or inappropriate use of the data in legal battles. There will be disadvantages to any type of monitoring. Government agencies and/or industry may seek to discredit community monitoring data or try to contradict it with their own information. Researchers or research institutions involved in a project may have goals that differ from the community's goals. The challenges are many but with proper planning, good partnerships, and a motivated community, monitoring can be a powerful tool. Networking with other communities that have overcome the many challenges involved will greatly strengthen any monitoring effort. We strongly encourage communities that are considering monitoring to learn directly from groups who have performed similar studies in the past. In compiling this handbook we have drawn on the experience of activists, community organizers, researchers, and policy advocates around the country. Two recurring themes emerged as fundamental lessons for community monitoring. First, that the most successful and long-lived projects are those that have the greatest degree of community involvement through all phases of the project. Second, the most successful campaigns included monitoring as a part of a broader strategy, including components like community mobilization, education and capacity building, technical information and research, legal strategies or media campaigns. Newspaper Ad produced by Environmental Working group in the campaign to get arsenic out of pressure-treated wood products. Appendix A: Survey The following survey was used by participants in each of the projects profiled. Case Study Name ___________________ BASIC DATA 1. What geographical area was the focus of your monitoring project? 2. What kind of monitoring tools or techniques did you use? 3. What kinds of chemicals did you look for? a. Did you carry out any preliminary research but consulting Centers for Disease Control or other government agency information? b. Are there particulat population(s) at risk (age-stratified, racial / ethnic groups, class / income?) c. Has there been government testing? d. What is the generally accepted exposure route for this chemical: e. What are the health or environmental effects / risks from exposure 4. Who conducted the monitoring? (community groups, independent research labs, policy institutes, universities?) 5. What is the goal of monitoring effort/campaign (immediate, long term)? (Are there corporate or government targets?) THE SPECIFIC EFFORT / PROJECT 6. Background context of monitoring effort: a. How did community become aware of problem? b. How and where this movement began? c. What are the concerns of the community ? How did community become mobilized? Any particular triggers? 7. Methods employed (be as detailed as possible) 8. Research Process: a. How did community design research / monitoring effort / what part did community play in formulating research questions? Research design? Data gathering? Analysis? Interpretation? Dissemination? b. How did partner agency / organization (if any) design research / monitoring effort / what part did agency / organization play in formulating research questions? Research design? Data gathering? Analysis? Interpretation? Dissemination? 9. What are the Data / Results / Findings of study? FOLLOW-UP: 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Is the resulting monitoring data available to public? How have local residents responded? How have local businesses responded? Have there been legal / policy changes? Is the community still mobilized, do community organizations still exist, is there local activism? Is the specific monitoring effort still ongoing? What are the other outcomes? (of study, of mobilization, of legal suit or policy campaign) INTERNAL PROJECT EVALUATION 17. If another community organization wanted to replicate this project, how easy or hard is it? What sorts of commitments? a. How much work was required to get data in terms of hours? b. What kinds of factors affected data collection? Example: environmental / outside factors that affect data collection like precipitation, seasonality, fish migrations, traffic congestion and rush hour commutes) c. What kind of technical expertise did you need to to design your project? To carry out data gathering? To carry out data analysis? To interpret data? d. How much did the project cost in terms of equipment or testing samples? e. What sorts of community knowledge contributed to the monitoring effort? 18. In hindsight, what would have done differently? What do you think were your keys to success? What advice to other communities who want to do a similar study? 19. How difficult was it to translate technical knowledge into lay language and concepts? What steps were involved? 20. How difficult was it to translate study results into health recommendations? What kinds of policy recommendations emerged from your project? How was it done? Who made the decisions? 21. Are there next steps or follow up work? 22. Contact information or web links.