The relationship between work characteristics, wellbeing

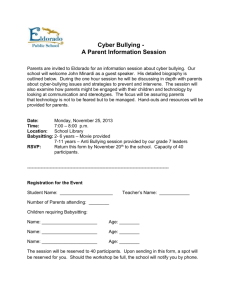

advertisement