Nimrod v Keetmanshoop Municipality final

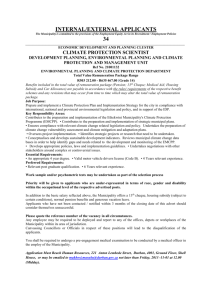

advertisement