Developing a Measure of Interest-Related Pursuits

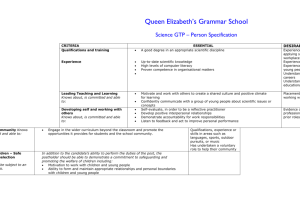

advertisement