Social skills group free play.

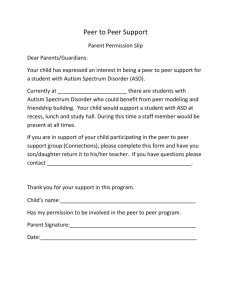

advertisement