Source Sensibility

advertisement

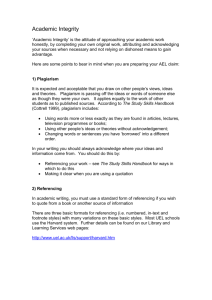

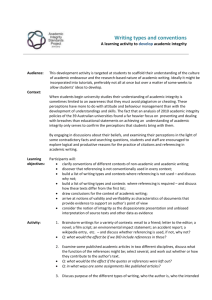

Getting at the Source: A Historical Look Source Sensibility By now, you have attained all but complete mastery in producing a solid 3-5 pager only hours before it’s due. However, with a more lengthy research assignment, the questions that you are expected to encounter and engage at this, the university level, are typically not questions easily answered on the first page of a Google search or in even a 5 page paper, and can often not be chalked up to common knowledge. In order to convince others of your argument, you will need to rely on the current pool of knowledge—in scholarly discourse, sources. Referencing? The practice of acknowledging your sources, the works of intellectual discourse that lend themselves in some way to the development of your own ideas, is termed referencing. But why reference? Reasons to reference Western academia recognizes 7 distinct reasons we engage in this practice: Roots of Referencing: 1-3 From the Classical Period until the advent of the printing industry, avoiding plagiarism was not the reason referencing occurred. In fact, classical academia relied on imitation of the works of others. What we now deem to be plagiarism was only a laughing matter until fairly recent in human history.i In the oral tradition, references were made to inform connection between ideas, to validate an argument or to pay attribute to another scholar. The Citation Culture is a more recent phenomenon. 1. Connecting ideas Knowledge knows no temporal boundaries. Using sources allows you to draw carefully crafted conclusions with differing connected groups of ideas supported by references. 2. Validating arguments Our academic tradition relies on arguments that are made through use of sound reasoning. This is done not only through selection of particular data, but also through use of reliable sources to back your claim. 3. Displaying an attitude of gratitude Referencing is a way to pay tribute to those who contributed to the pool of knowledge by offering up their work to be subjected to review. It is showing courtesy and respect to those who provided the materials for you to formulate your own ideas. Creation of a Citation Culture: 4-7 The commodification of culture more generally produced a changing political economy of documentation that continues to perpetuate itself. The Western system of documentation is not the ‘right’ way to produce scholarship. It was not initially intended to advance scholarly discourse or to produce better intellectuals. Considering that the imitation culture prevailed for so long in the Western world, and is still in existence Duke Writing Studio 2 in other cultures, citation culture is likely not inherent nor natural.ii However, it is the norm in Western academic writing, so it is important to continue the practice, at least for the present. 4. Mapping the origins of ideas A part of being able to engage in any intellectual discourse is understanding the context from which this knowledge arose. Referencing allows for the tracing of ideas throughout various moments in human history to their original contexts. A Brief History: When trying to trace the origins of ideas prior to the 1700s, it is nearly impossible.iii Even a phrase like “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” which we commonly attribute to Sir Isaac Newton, was commonly found in literature at the time in which he published it. Prior to the eighteenth century, hardly a single piece of work can be called the original. The predominant culture until this point was one of imitation.iv 5. Avoiding plagiarism Perhaps the most commonly citied reason for referencing, plagiarism, a form of academic dishonesty that can result in serious consequences, is a Western notion birthed from capitalism that lends itself entirely to the advent of the practice we recognize as referencing today. A Brief History: The term plagiary did not enter the lexicon of the English vernacular in the way we recognize it today until the nineteenth century. Prior to this point, the word referred to a person who kidnapped a child or slave. Plagiarism only came to connote a thief of words or ideas with the invention of the printing press and move away from a feudalistic economy in Western Europe.v 6. Instilling a sense of authorship References allow you the freedom to take a specific position using select evidence to advance your claim. You can also continue to write with your voice in your style, and maintain the freedom to choose your outlook, to choose what you specifically want to present, and to draw your own conclusions on a set of ideas. A Brief History: The idea that one could own words or ideas is a fairly recent phenomenon. It occurred at the end of Elizabethan England and coincided with the economic shift from feudalism to capitalism. The Statute of Anne, provided the first legislation that established the notion of intellectual property.vi 7. Passing along knowledge Referencing allows readers to actively engage in the work of the writer and to potentially pursue further study using evidence presented. The advent of bibliographies and citation indexes are useful for this purpose. A Brief History: In 1960, as scholarly journals increased in popularity, and intellectual property law was growing in the global consciousness, the first citation index was invented by the Eugene Garfield Institute for Scientific Information for articles produced in academic journals. This allowed for scholars to build credentials and attain tenure based on the number of references their publications produced, which many deem as the corruption of modern scholarship.vii Duke Writing Studio i Thomas Mallon. Stolen Words. (San Diego: Harcourt, 2001) 3. Colin Neville. The Complete Guide to Referencing and Avoiding Plagiarism. (Maidenhead: Open UP, 2007) 7. iii Anthony Grafton. Forgers and Critics: Creativity and Duplicity in Western Scholarship. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1990.) 36 iv Thomas Mallon. Stolen Words. (San Diego: Harcourt, 2001) 6. v Thomas Mallon. Stolen Words. (San Diego: Harcourt, 2001) 6. vi Adam Moore. “Intellectual Property”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)). vii Tim Parks. "The New York Review of Books." The Writer’s Job by Tim Parks. The New York Review of Books, 28 Feb. 2012. ii 3