Reviewer 1 report (DE Jarbol) Responses to reviewer New or

advertisement

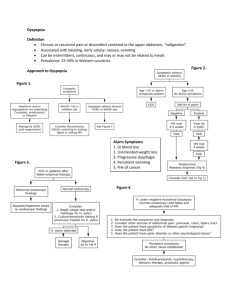

Reviewer 1 report (DE Jarbol) 1. Some key baseline assumptions were included in the model. It is hard to understand the rationale behind all the assumptions. Assumption no. 4: If there is no relief of symptoms after initial management, or if symptoms recur, an endoscopy will be offered; However, relief of symptoms will not be expected in all patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia, treated for H pylori infection. Further, the fluctuation of dyspepsia symptoms is well-known and severity as well as symptoms may vary in the same patient over time. The evidence to support the assumption concerning endoscopy to all people < 55 years with recurrence of symptoms or no relief of symptoms after initial management is not fully reliable. The assumption needs further explanation. 2. Assumption no. 5: The rationale for long-term PPI therapy here is not understandable and needs further explanation. 3. Probabilities employed in the model were based on published literature where available and where necessary, the numbers were supplemented with expert opinion based on experience treating dyspepsia patients. Limitations of this approach Responses to reviewer We agree that there is not evidence to support the practice of endoscopy for all patients in the setting of non-relief or recurrent symptoms. Yet this reflects the common gastroenterology practice in our own community, and we believe it is likely to be common across much of the U.S. Our decision model was designed to assess costeffectiveness of initial diagnostic tests, not costeffectiveness of the full algorithm, but the only way to determine this is by modeling the full care process. Thus, we started with what we believe to be a common practice pattern, rather than with an idealized practice pattern. And then we determined the impact of the choice of diagnostic test given that practice pattern. Same Agree that this is an important limitation, and may not have been clearly enough acknowledged in the Discussion section. New or changed text in the manuscript Changed title to include the phrase “Assuming a High Resource Intensity Practice Pattern”. Also, at the beginning of the Methods section, added "In order to calculate the impact (both cost and benefit) of the choice of diagnostic test we had to first create a model of the expected care process for these patients. We intentionally did not use an idealized care process, but rather modeled it to reflect typical local practice for managing dyspepsia (Figure 1). We also believe it to be a reasonable representation of practice patterns for dyspepsia across much of the US." Under Assumption 4, added "This assumption was followed not in an attempt to reflect evidence-based practice, but rather in an attempt to reflect a “typical” approach to dyspepsia management." Under Assumption 5, added "As above, this assumption was followed in an attempt to reflect typical practice patterns, rather than evidence-based practice per se." Modified paragraph in Limitations section to read "The primary limitation of our analysis was our set of clinical assumptions. These results should not be considered to have validity outside of those should be discussed. 4. The incremental costeffectiveness ratios for each strategy are presented in table 5. However, the results are not reflected in the discussion 5. The discussion and conclusion is not quit well balanced and supported by the data in the way that the authors conclude that ?in the initial choice of noninvasive testing strategy does not have a significant influence on the overall quality and cost for care for patients presenting with previously uninvestigated dyspepsia. The data does not support much about the quality of care for patients. assumptions. This includes both the assumed practice pattern (Figure 1) and the numbers (costs and probabilities). In clinical settings that do not fit these assumptions our results may not apply." On further reflection, the ICER numbers as originally presented here may confuse rather than enlighten readers. For one thing, we used as our denominator symptomfree years rather than QALYs, yet most published ICER analyses are presented as incremental cost per QALY. Second, our ICER analysis was based on the mean costeffectiveness results, but our discussion emphasizes the spread of the results, i.e. the high degree of overlap in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Finally, the results are described entirely by Table 3 and Figure 2. Accordingly, we deleted the ICER table. The discussion section was using "quality and cost of care" as being synonymous with the cost effectiveness measure used in our study, namely cost per symptom free year. This is potentially ambiguous, and the reviewer may have had a different definition of "quality of care" in mind. We adjusted our language accordingly. Deleted Table 5 and the references to Table 5. Changed "quality and cost of care" to "cost-effeciveness of care" 6. The authors are aware of the limitations of their analysis in the set of clinical assumptions but I am not convinced about the representatives of the results. Minor essential revisions: 1 Table. 2: Variable1: Prevalence. I guess it is the H pylori prevalence, but this should be clarified. Discretionary Revisions The authors prepare the ground for a debate of the issue of which non-invasive H pylori test strategy should be used in the management of uninvestigated dyspepsia, but also include empiric proton pump inhibitor trial in the model. The reason for this is not fully explained in the text. 2. The authors include serologic tests in the model, and argue that serology is more widely used than would be expected under the recommended approach. However, the serologic tests are not recommended due to inferior sensitivity and specificity, and are therefore not interesting from a clinical point of view. 3 The choice of cost per symptom free year rather than cost per correct diagnosis as primary outcome is discussed in the text. The aspect considering a correct diagnosis of H pylori, including confirmation of the eradication treatment effect, in the light of preventing future ulcer disease, ulcer complications and cancer disease is, however, not discussed. See our response and changes corresponding to item 3 above. Change made Changed to "H. pylori prevalence " We felt that empiric PPI therapy should be included for completeness, both because it is a legitimate management option and because in a sense it represents a type of noninvasive diagnostic strategy. Added to first paragraph of Methods: "The first step of strategies 1 through 5 was a different noninvasive test, and empiric PPI therapy was included for completeness as a sixth strategy" Agree that serology is not recommended, and this is stated in the introduction. We disagree that they are not clinically interesting, specifically because they are widely used (also as described in the introduction). Although HP eradication theoretically should reduce the risk of cancer as well as ulcer complications, we felt that there was insufficient evidence regarding the magnitude of this effect to attempt to model longterm benefits of HP eradication. The purpose of providing this information was clarified as "Some previously published costeffectiveness analyses have reported results in the form of mean cost per correct diagnosis; to allow easier comparison with these we provide cost per correct diagnosis in Table 4." 4 The cost perspective taken was social, however, the analysis considered only direct costs which mean that the indirect costs were not included, which could have been discussed. Currently recommended practice for costeffectiveness analysis is to include only direct medical costs, as opposed to indirect costs such as time off of work, etc. The term "societal perspective" is fairly standard in costeffectiveness analysis and is meant to reflect aggregate medical cost impact as opposed to the portion paid by the patient, the hospital, the insurance company, etc. No change. This overlaps with Reviewer 1's first item, addressed above. Again, our intent was to compare cost-effectiveness just of the diagnostic testing portion of care, not compare costeffectiveness of therapeutic approaches, and in order to do this we had to pick a "typical" model of care. With specific regard to eradication testing, we did not test this specifically but it probably would not have impacted the results signficantly given that in most of these patients, eradication does not result in dyspepsia relief -thus, most would receive endoscopy anyway under our assumptions. See changes made above in conjunction with response to Reviewer 1's first comment. Reviewer 2 report (Dr. Xavier Calvet) 1. Despite the study deals with a low-risk for cancer population (less than 55 y old, no alarm symptoms), the authors assumed that all patients whose symptoms relapsed either after triple therapy or a PPI trial will receive an expensive endoscopy. By contrast, as suggested by Spiegel et al. (Gastro 2002), it seems more reasonable to test for H. pylori and treat the infection in patients failing empirical PPI therapy before endoscopy. It would also be preferable to test patients who had received eradication treatment for cure of H. pylori infection with and UBT before endoscopy. Did these plausible different approaches change the study conclusions? 2. Prevalence of H. pylori infection is given for the US general population. However, this results are applicable neither to other countries (for example, Central and South-American, Mediterranean, African or Asian countries) nor to specific populations in the US (as Afro-American, Hispanic or Asian), that have an Hp prevalence around 60%. Are the conclusions of the study the same with such high prevalence? 3. The same applies for costs, which could markedly change from country to country. How did major differences in the cost of the tests influence the study conclusions? 4. Values of sensitivity and specificity are generous, especially for serology and stool tests. It should be remembered that the different kits show marked differences in sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity may be very low depending on the stool kit or even the methodology of the urea breath test ( Calvet et al., Clinical Infectious Diseases). In addition, as variability of serology accuracy is even larger, its use is not recommended We tested across prevalence ranging from 5-40%, which we agree would not be sufficient to extend these results to other countries. However, the main limitation in attempting to apply these results outside the US is more likely to be the practice pattern assumptions. Countries which are more resourcesensitive (e.g. UK) or resource-deprived (e.g. developing countries) would have very different practice patterns for diagnosing and managing dyspepsia, and our findings would likely not apply. Given that the underlying model of clinical practice for dyspepsia would likely not apply to most other countries, we did not attempt to model cost differences other than what would be expected in a typical US practice setting. We performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis across a range of sensitivity and specificity for each test that we considered reasonable given our literature review. Our ranges didn't go quite as low as 70%, nor did we separately analyze what the costeffectiveness would be at that low end of test performance. However, given our results, it is unlikely that this would See changes made above in conjunction with response to Reviewer 1's third comment. Same as above. Added the following sentence to the Discussion: "To use a more extreme illustration, a consequence of our underlying model is that the diagnostic test could be replaced with a random number generator without significantly impacting cost-effectiveness. " provided local validation was performed (Maastricht guidelines). What happens in the model when values of sensitivity and specificity for serology are decreased to, for example, 70%? 5. Obtaining the values for assumptions of different studies instead from direct comparative trials leads to bizarre results. Values coming from different studies heavily depend on the differences in the baseline characteristics of the populations evaluated instead of reflecting true differences of the efficacy of the treatments. So, for example, the study assumes that, after eradication, the probability of symptom relapse at one year is higher in patients with peptic ulcer than in those without. By contrast, in the few available randomized trials, the one-year probability of symptoms relapse in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia after a PPI trial is near 100% (Rabeneck, AJG, Marmo BMJ) whereas probability of relapse is far lower after eradication treatment in H pylori positive patients (Marmo BMJ). What happens in the model when these different values are incorporated? have made any difference. Stool antigen testing was modelled as being less expensive than serology and much more accurate, yet the model did not predict it to be significantly more costeffective. As pointed out in the Discussion, this appears to be a consequence of our underlying clinical practice pattern assumptions. Agree with the reviewer about the problematic nature of using assumptions derived from different comparative trials. For our study, we chose to heavily weight the findings of the following Cochrane review: Moayyedi P, Deeks J, Talley NJ, Delaney B, Forman D. An update of the Cochrane systematic review of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in nonulcer dyspepsia: resolving the discrepancy between systematic reviews. Am J Gastroenterol 2003 Dec;98(12):2621-6. This review found that for patients with nonulcer dyspepsia and confirmed HP infection, eradication therapy provided only a small average benefit. This review thus has quite different conclusions from the articles the reviewer cites here. Nonetheless, we added language in the limitations section to Added the following to the Limitations section: "Finally, our analysis relied heavily on the findings of a Cochrane systematic review in which H. pylori eradication was found to have only a very small clinical benefit for the average patient with nonulcer dyspepsia. Our findings may thus not apply to patient subsets for which eradication therapy could be shown to have a larger average benefit. " clarify that our findings would not apply to patient subsets where eradication therapy could be shown to have a large effect in reducing symptoms.