Dysphagia, GERD, H pylori - UNM Internal Medicine Resident Wiki

Upper GI potpourri

Anthony Worsham, MD

Division of Hospital Medicine

Department of Internal Medicine

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center

Thursday, October 9, 2014

Outline

● dyspepsia

● gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

● peptic ulcer disease

●

Barrett’s esophagus

●

Helicobacter pylori

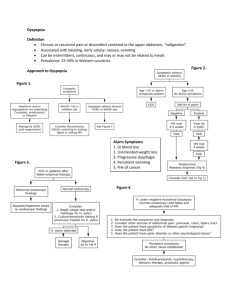

What is dyspepsia?

Functional dyspepsia

“presence of symptoms thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, in the absence of any organic, systemic, or metabolic disease”

Rome III diagnostic criteria (at least 1 of)

Bothersome postprandial fullness

Early satiation

Epigastric pain

Epigastric burning

No evidence of structural disease

Functional dyspepsia

Differential diagnosis

Functional (nonulcer) dyspepsia

Peptic ulcer disease

Reflux esophagitis

Gastric or esophageal cancer

Abdominal cancer, especially pancreatic cancer

Biliary tract disease

Carbohydrate malabsorption (lactose, sorbitol, fructose, mannitol)

Gastroparesis

Hepatoma

Infiltrative diseases of the stomach (Crohn disease, sarcoidosis)

Intestinal parasites (Giardia species, Strongyloides species)

Ischemic bowel disease

Medication effects (Table 3)

Metabolic disturbances (hypercalcemia, hyperkalemia)

Pancreatitis

Systemic disorders (diabetes mellitus, thyroid and parathyroid disorders, connective tissue disease) Rare

Loyd RA and McClellan DA. Update on the evaluation and management of functional dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician

2011; 83(5): 547-552

Up to 70 percent

15 to 25 percent

5 to 15 percent

< 2 percent

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

Rare

●

Upper gastrointestinal alarm symptoms

Age ≥55 years with new onset dyspepsia

●

Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding

●

Dysphagia

●

Progressive unintentional weight loss

●

Persistent vomiting

●

Iron deficiency anaemia

●

Epigastric mass

●

Suspicious barium meal result taken from National Institute for Health and Care (formerly Clinical) Excellence referral guidelines for suspected cancer

Functional dyspepsia treatment

Diet and lifestyle

–

–

– weight loss smoking and alcohol cessation

Avoid certain foods (e.g., fatty foods)

Medication

–

–

–

– acid suppression therapy (e.g., PPIs)

H. pylori eradication therapy prokinetic drugs (e.g., metoclopramide, cisapride, domperidone) antidepressants and psychologic therapies

Alternative therapies (e.g., accupuncture)

Ford AC. Dyspepsia. BMJ 2013;347:f5059

What is GERD?

Definition

“GERD should be defined as symptoms or complications resulting from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus or beyond, into the oral cavity (including larynx) or lung. GERD can be further classified as the presence of symptoms without erosions on endoscopic examination (nonerosive disease or NERD) or

GERD symptoms with erosions present (ERD).”

Katz et al, Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol

Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. Failure of reflux inhibitors in clinical trials: bad drugs or wrong patients? Gut 2012;61:1501 –1509.

Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. Failure of reflux inhibitors in clinical trials: bad drugs or wrong patients? Gut 2012;61:1501 –1509.

GERD treatments

● lifestyle modification

● medication

● surgery

Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. Failure of reflux inhibitors in clinical trials: bad drugs or wrong patients? Gut 2012;61:1501 –1509.

Top 100 Most Prescribed, Top Selling Drugs.

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/825053

PPI Complications

● community-acquired pneumonia

● hip fracture

● infectious gastroenteritis

●

C difficile

●

Vitamin B12 deficiency/malabsorption

● secondary hypergastrinemia

● hypochlorhydria

Kahrilas PJ, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, NEJM 2008;359:1700-7.

Katz et al, Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:308

Peptic ulcers can be deadly

Rudyard Kipling J. R. R. Tolkien James Joyce

Ulcer complications

● bleeding

● perforation

● penetration

Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer

Clinical status

●

At presentation

Assess hemodynamic status (pulse and blood pressure, including orthostatic

●

●

●

● changes).

Obtain complete blood count, levels of electrolytes (including blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), international normalized ratio, blood type, and cross-match.

Initiate resuscitation (crystalloids and blood products, if indicated) and use of supplemental oxygen.

Consider nasogastric-tube placement and aspiration; no role for occult-blood testing of aspirate.

Consider initiating treatment with an intravenous proton-pump inhibitor (80-mg bolus dose plus continuous infusion at 8 mg per hour) while awaiting early endoscopy; no role for H2 blocker.†

●

●

Perform early endoscopy (within 24 hours after presentation).

Consider giving a single 250-mg intravenous dose of erythromycin 30 to 60 minutes before endoscopy.

●

Perform risk stratification; consider the use of a scoring tool (e.g., Blatchford score16 or clinical Rockall score17) before endoscopy.

At early endoscopy

Perform risk stratification; consider the use of a validated scoring tool (e.g., complete

Rockall score17) after endoscopy.

Low-risk lesions

Gralnek IM, et al. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. NEJM 2008;359:928-37

Recommended treatment to prevent ulcer rebleeding

Laine L and Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:345

–360;

Peptic ulcer treatment

All NSAIDs are associated with GI bleed

Barrett’s esophagus

Spechler SJ and Souza RF. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2014;371:836-45.

Helicobacter pylori

H . pylori treatment regimens

Triple therapy (7-14 days)

– PPI, healing dose bid

– amoxicillin 1 gm bid

– clarithromycin 500 mg bid

Sequential therapy

– Days 1-5

–

●

●

PPI, healing dose bid amoxicillin 1 gm bid

Days 6-10

●

●

●

PPI, healing dose bid clarithromycin 500 mg bid tinidazole 500 mg bid

Quadruple therapy

– PPI, healing dose bid

– tripotassium dicitratobismuthate, 120 mg qid

– tetracycline 500 mg qid

– metronidazole 250 mg qid

Healing dose PPI (all bid)

– omeprazole 20 mg

– pantoprazole 40 mg

– lansoprazole 30 mg

– esomeprazole 20 mg

H. pylori testing

Testing criteria

●

Active gastric or duodenal ulcer

● history of active gastric or duodenal ulcer not previously treated for H. pylori infection

● gastric MALT lymphoma

● history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer

● uninvestigated dyspepsia

Test-and-treat criteria

● age <55 yr and no alarm symptoms