FREC 424 -- Population and Development

advertisement

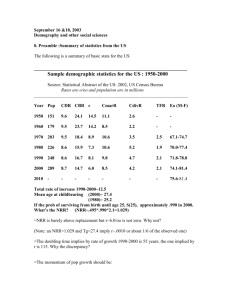

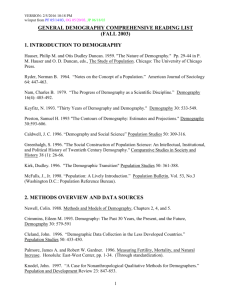

FREC 424 -- Population and Development Concerns over population growth date back to the 18th Century (Malthus). Population growth reflects food constraints, disease, income levels and distributions, cultural norms, parent incentives and preferences. Columbus's discovery of America had a huge impact on world populations: Europeans brought tuberculosis and small-pox to America which literally decimated Native American populations, while the introduction of the American potato to Europe increased food productivity and permitted rapid population growth in Europe, ultimately providing the labor resources for the Industrial Revolution. In general, higher-income nations have lower population growth rates. These nations have higher infant survival rates thanks to better medical care, but lower live birth rates. This reflects better availability of contraception, and preferences for later marriages and fewer children. Since birth-rates don't account for the age structure of the population, the US Census calculates a total fertility rate, which is the number of live births the average woman has in her lifetime. The total fertility rate yielding a stationary population is the replacement rate; in the US, this is 2.11 children per woman. The US has been below this rate since 1972. Population Growth and Economic Growth Population growth may increase or decrease economic growth. If the marginal productivity of people exceeds the marginal cost, more people increases total output, but unless marginal productivity is also above average productivity, more people reduces per capita output. Theory suggests that fixed factors such as land imply declining marginal productivity of labor. However, technologies enhance the marginal productivity of labor over time. Economies of scale may also be supported by population growth. A nation’s age structure defines the proportions of children, working-age adults and elderly in the population. Many developed nations have a large proportion of elderly citizens due to improved health care. The “elderly effect” of retired citizens no longer working or consuming much tends to slow economic growth. Many LDC’s exhibit an opposite "youth effect" resulting from high birth rates that create a disproportionate number of young children in the population. Children divert women from work-force participation. Both effects reduce the proportion of the population in the work-force. The youth effect probably slows economic growth more than the elderly effect, since older people save more than younger people and create a larger savings pool supporting capital formation that enhances labor productivity. Countries exhibiting youth effects will tend to have lower savings, less capital and lower productivity per worker. The economic theory of fertility (Gary Becker and others) views children as investment vehicles. It is instructive to compare costs of, and returns to, children across socioeconomic groups or nations. High-income families have fewer children on average, and they can afford to invest more nutrition, education, etc. in each child, than low-income families. Most children survive to adulthood, so parents don’t need extra children to offset high child mortality. Parents have ready access to birth control. The marginal return to additional children in high-income families declines rapidly, and economies in developed nations offer many alternative forms of investment besides children. Wealthy parents do not need to depend on their children for old-age security. In contrast, children in capital-poor LDC's are low-cost and the marginal return to additional children is more constant (even small children can herd animals), so parents in LDC's compensate by having more children but investing less in each child. High child mortality creates an incentive to have extra children. Poor families have less access to contraception or control over family size. Children (particularly females) in LDC’s tend to have much lower educational attainment and consequently lower economic productivity as adults. Lacking other forms of investment, parents in LDC’s will often view their surviving children as a primary source of oldage security. Rapid population growth worsens income inequality by depressing wage rates vis-à-vis profits. The three-phase demographic transition model indicates economic growth ultimately reduces population growth. In the pre-industrial phase, societies exhibit fairly stable populations because high mortality rates compensate for high birth rates. In the transitional or “take-off” phase, the early stages of development unleash rapid population growth as mortality rates fall relative to birth rates. In the later phase of development, societies recover population stability as birth rates decline to match low mortality rates. The graph below suggests the world is mostly in this latter stage of development, where many wealthy countries now have fertility rates below their replacement rates. It also proves that, globally, children are inferior goods. 8.00 Fertility vs. Per-Capita GDP, 228 countries (source: CIA World Factbook 2002) 7.00 Fertility Rate 6.00 5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 0.00 2.50 3.00 Regression Results: Multiple R R Square Adj R Square Standard Error Observations ANOVA Regression Residual Total Intercept Ln(GDP/cap) 3.50 4.00 Log of Per-Capita GDP Fertility vs. Ln(GDP/cap) 0.7614 0.5798 0.5779 1.0757 228 df 1 226 227 Coeffs 12.4107 -2.5259 SS 360.7687 261.5117 622.2804 Std Err 0.5299 0.1431 4.50 MS 360.7687 1.1571 F 311.7785 t Stat 23.4197 -17.6573 P-value 0.0000 0.0000 5.00 Economic development forces traditional cultures to confront various cultural impediments to growth (such as low social status of women), and this process can create social unrest or conflict. Are parents' child-bearing decisions economically efficient for society? There is ongoing debate about this. Children involve significant social benefits and costs beyond the private benefits and costs that accrue to parents and drive their child-bearing decisions. Policies such as food subsidies and free public education for children, tax breaks for parents, etc. reduce the costs of children to parents, and are justified as long as the children yield a net social benefit. But where children are perceived to have a net social cost, policies to reduce fertility may be adopted. In addition to promoting contraception, India and China both tried very unpopular policies restricting families to one or two children each. Modeling the "market" for children, demand is shifted downward by industrialization; availability of alternative family savings vehicles; and decreases in infant mortality. Supply (marginal cost) is shifted upward by better job opportunities for women that increase the opportunity cost of having children; increasing food, housing and education costs (education costs include foregone children's wages). Over the past 20 years economists have identified the economic status of women as a critical leverage point for spurring development in LDC’s and controlling population growth. Many development programs are now targeted to providing birth control, education and economic empowerment to women. This strategy offers a range of secondary benefits. Educated women increase the skilled workforce. They demand better nutrition and health care for themselves and their children, and they have better incomes to provide these. Discussion question: Should there be a market for children (subject to child protection laws)?