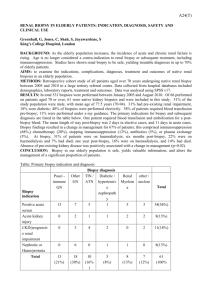

Renal Lab 2: Tubules, Interstitium and Vessels (March 25 or 26)

C604 Renal Lab 1: Tubules, Interstitium, Vessels

Case 1: (Answer: Acute tubular necrosis following severe intravascular volume depletion)

A 54-year-old man (82kg) presents to the E.R. with malaise, fatigue and oliguria two days after serving on a pit-cr ew during the Indianapolis 500 race. Despite sunny skies and temperatures that hovered in the 90’s, he wore a full-body, fire-proof insulated suit and helmet so the he could change tires for a car that placed 28th out of 33 cars. He drank three 24-ounce bottles of purified water (2.1 liters) over eight or nine hours that day. He appears pale and his heart rate is 90/min, BP 108/60 mmHg, temperature 99.8

F but he has no other physical findings. A stat serum creatinine = 5.8mg/dL, BUN = 70 mg/dL and hematocrit = 49%. You admit the patient and observe that over the next eight hours he has made only 60cc of urine and his serum creatinine is now 6.3 mg/dL.

Questions:

A) What is the most likely reason for decreased urine output? Ischemia from intravascular volume depletion and subsequent decreased renal blood flow and tubular damage. Renal tubules are damaged as a consequence of ischemia leading to depleted ATP.

B) What problems is this patient having because of poor urine output?

Hyperkalemia, acidosis, volume overload including pulmonary edema.

C) What other laboratory values would you want to know?

Urinalysis and urine microscopy for blood, protein, glucose, WBCs, etc.

Draw blood from vein to measure levels of:

1. potassium for possible hyperkalemia, which may cause cardiac arrhythmias.

2. bicarbonate (HCO

3

) as an indicator for acidosis. Kidneys and lungs balance levels of carbon dioxide (CO

2

), bicarbonate (HCO

3

), and carbonic acid (H

2

CO

3

) so that blood does not become acidic (acidosis) or basic (alkalosis). More than 90% of CO

2

in blood exists in the form of HCO

3

, which may also be measured in an arterial blood gas (ABG) test.

D) What therapy might be necessary? renal replacement therapy (dialysis)

E) Would you perform a renal biopsy on this patient and how might that change clinical management?

Biopsy may not be indicated if clinical history and lab testing fit ATN. If multiple etiologies are possible (e.g., glomerulonephritis or drug reaction), then tissue examination may be needed.

1. Whole, intact cells may separate from tubular basement membranes (TBM) and float into urine.

Highly susceptible cells are in the straight portion of the proximal tubule and the thick ascending limb (TAL). TAL secrets Tamm-Horsfall protein (hyaline).

2. Parts of the cell may detach, such as the apical brush borders or “blebs” of cytoplasm, which may appear like granular debris in tubule lumina.

3. Intact cells or pieces of cells aggregate downstream with Tamm-Horsfall protein to form cellular casts that can occlude the tubule lumina. These casts have a muddy brown color when urine is examined with a microscope. TammHorsfall casts that lack cells are sometimes called “hyaline casts”.

4. Mitotic figures and flattened/squamoid cytoplasm indicate regeneration of epithelial carpet that covers TBM. Irreversible damage may follow TBM rupture (tubulorrhexis).

5. Interstitium may contain inflammatory cells as a reaction to ATN. Glomeruli are normal.

G) Why is radiocontrast a bad idea in this patient? Contrast is not a good idea in a patient with ATN

(exacerbates pre-existing acute injury).

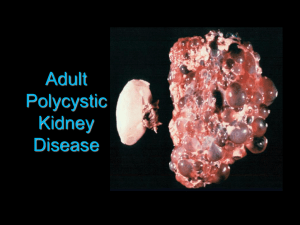

Case 2: (Answer: Acute cellular rejection in transplant recipient)

A 48-year-old postal worker (60 kg female) presents to you three months after receiving a living-related renal allograft for chronic kidney disease secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The patient's last serum creatinine two weeks ago was 1.2 mg/dl. Laboratory results from this visit reveal a serum creatinine of 1.9 mg/dl and a cyclosporine level of 400 ug/l by monoclonal RIA (elevated). On the exam the patient has a blood pressure of 160/95 mmHg and she is slightly tender over her graft sight. She started back to work this week.

Questions:

A) What is the differential diagnosis associated with this acute clinical presentation?

List differential diagnoses under categories of pre-renal, renal and post-renal.

B) How can you clinically distinguish between the categories of pre-renal, renal and post-renal??

1. Pre-renal: history consistent with orthostasis, newly prescribed diuretics, GI loss or decreased fluid intake, fever, etc.; exam findings for intravascular volume depletion/hypovolemia, e.g. orthostasis, poor skin turgor

2. Renal: history of transplant; new meds; systemic or multisystem illness; negative exam.

3. Post-renal: history - symptoms of prostatism; abdom surgeries, etc; exam: suprapubic tenderness/bladder distension

C) If you suspect that cyclosporine A is the cause of acute renal failure, how is the diagnosis made? How would you treat the patient?

Either clinically by history or changing dosage and/or levels, or by biopsy. Treat by decreasing the dosage.

D) Would you perform a renal biopsy on this patient and how might that change clinical management?

Diagnosis: Acute cellular rejection: normal glomeruli and vessels, but tubulitis is present (T cells or T lymphocytes in tubule wall). Tubulitis is scored according to Banff criteria [Kidney Int. 1999

Feb;55(2):713-23; Am J Transplant. 2012 Mar;12(3):563-70; Am J Transplant. 2014 Feb;14(2):272-83.].

Compare to cyclosporine toxicity or Prograf toxicity (a more commonly used calcineurin-class drug) with isometric vacuolization of proximal tubule cell cytoplasm and transmural hyaline deposition

(glassy pink material) in walls of arterioles. IF and EM are not needed for scoring acute cellular rejection.

Case 3: (Answer: Interstitial nephritis secondary to antibiotics)

An 18-year-old female presents with complaints of a diffuse rash. Ten days ago the patient was prescribed cephalexin for a lower extremity cellulitis that developed after scratching a mosquito bite. She states the cellulitis improved but yesterday when a rash appeared on her chest and legs she started taking ibuprofen. On exam the patient has a temperature of 101.5

F and a diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash. Her serum creatinine is 2.5 mg/dl and differential white blood cell count reveals 10% eosinophils (absolute count 1000).

Questions:

A) What would you expect to see on urinalysis?

WBC's individually or in casts (mostly lymphocytes and some neutrophils and eosinophils but these are hard to differentiate in the urine). Eosinophils may be detected by their bright pink-red cytoplasm using Hansel stain or Wright stain, but these tests have low sensitivity and specificity, and thus are considered by some labs to have low yield. Also may detect low-grade proteinuria on urine reagent dipstick. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Nov;8(11):1857-62; Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989 Nov;113(11):1256-8.

B) What other laboratory tests would you order?

This is a classic presentation of acute intersitial nephritis (AIN) secondary to a drug reaction

(antibiotic). No other tests are necessary unless multiple etiologies are suspected or the patient’s renal function does not improve over time.

C) How would you manage the patient? Is a renal biopsy necessary?

Stop the antibiotic. Would expect patient to start to recover renal function within about one week.

Creatinine might continue to rise until then and patient might be oliguric. If renal function is not improving by 1 week, consider performing a renal biopsy procedure. If diagnosis confirmed, consider steroids as a possible therapy. Kidney Int. 2010 Jun;77(11):956-61; Nephrology (Carlton). 2012

Nov;17(8):748-53.

D) What would the renal biopsy show?

1. Light microscopy: Glomeruli and vessels are usually normal. The interstitium contains infiltrates of

T lymphocytes (major cell component) with eosinophils. Also present but in less numbers are macrophages, plasma cells, and neutrophils. In mild cases of AIN, the tubules appear normal.

Interstitial cells and edema push the tubules apart such that they are no longer be ‘back-to-back’, which increases the distance between tubules and peritubular capillaries. Tubulitis may occur if lymphocytes leave the interstitium and enter the tubules. Secondary ATN may occur from inflammation.

Differential diagnosis:

1. Neutrophil count is relatively low in the interstitum of patients with AIN, but if excessive they may indicate an alternative diagnosis such as acute pyelonephritis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013

Jun;18(6):463-7

2. Malignant lymphoma or plasma cell dyscrasia may involve the kidney and imitate AIN.

2. IF and EM are not required to diagnose AIN (other than to exclude glomerulonephritis, as glomeruli should be negative/normal by IF and EM).

Case 4: (Answer: Thrombotic microangiopathy c/w malignant hypertension)

A 40-year-old man (70 kg) presents with complaints of headache that has increased in severity over the last several days and has been associated with blurred vision over the last 12 hours. Blood pressure is 230/135 mmHg. He has S4 gallop on auscultation of the heart. Urine dipstick detected blood and protein.

Questions:

A) You refer the patient to the ER where your fellow intern sees this patient. What would be important signs to elicit on physical exam?

Fundoscopic exam (retinal hemmorhages, exudates, papilledema), abdominal bruit, multiple ectopy or tachycardia, crackles or tachypnea (pulmonary edema), asymmetric pulses suggesting dissection of aorta.

B) What laboratory tests would you order?

BUN & creatinine for renal function.

Urine microscopy to check for RBCs and RBC casts (casts confirming glomerulus as origin of hematuria).

C) What treatment would you immediately begin?

Lower BP with intravenous drugs slowly to 160/90 mmHg range. Monitor for signs of organ ischemia

(mental status changes, angina, decreasing urine output).

D) The next morning, with excellent management, the BP is 156/92 mmHg and serum creatinine is 2.9 mg/dL.

What would you do next?

Put patient on oral meds and wean the intravenous drugs keeping blood pressure in the 140-160/90-

100 mmHg range and slowly bringing BP down to <130/80 mmHg over several days.

E) When is a kidney biopsy indicated? Biopsy only if proteinuria and hematuria persist (i.e., other underlying causes of glomerular disease) or if serum creatinine continues to climb over the next few days. What would the biopsy show?

1. Light Microscopy:

A. Vessels show features of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA): a. fibrinoid necrosis (eosinophilic, smudged material, may react with anti-fibrin antibody), b. onionskinning or hyperplastic arteriolitis: concentric layers of proliferating intimal smooth muscle cells and collagen, c. mucinous (myxoid) degeneration: loose, blue material in the vessel wall, d. fragmented RBCs in lumina of arteries, arterioles, and glomerular capillaries

B. Glomerular lesions are characterized by ischemic alterations (wrinkled GBM), hemorrhage, thrombosis and fibrinoid necrosis.

If the patient’s malignant hypertension is superimposed on pre-existing benign hypertension, then vessels may contain hyaline deposits (chronic) along with f ibrin (acute). “Hyaline” in a vessel refers to

PAS-positive material (glassy-pink on H&E) and is defined as nonspecific accumulation of plasma proteins and lipids along the endothelium.

2. IF: +/- detect fibrin (antibodies to IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C4, C1q usu. negative/noncontributory).

3. EM of glomeruli would show widened subendothelium with granular, flocculent material along inner aspect of GBM. Electron dense (immune-type) deposits are usually absent.

TMA may occur from malignant hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis, antiphopholipid antibody syndrome, drug toxicity (e.g., Prograf), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) associated with shiga toxin or invasive pneumococcal infection, atypical HUS (aHUS), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Nephrol Dial

Transplant. 2012 Jul;27(7):2673-85. Correlation of clinical and laboratory data is required to identify etiology.

F) The patient is scheduled for follow-up with his primary care physician in one week. What other studies would be appropriate as an outpatient? If patient does not have history of longstanding hypertension or a family history, then work up for secondary causes of hypertension, such as renal artery stenosis, would be appropriate. Rimoldi et al: Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur

Heart J. 2013 Dec 23.