Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Using Light Emitting

advertisement

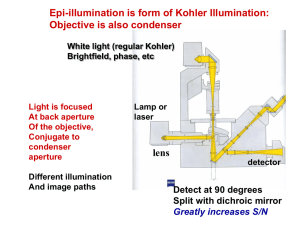

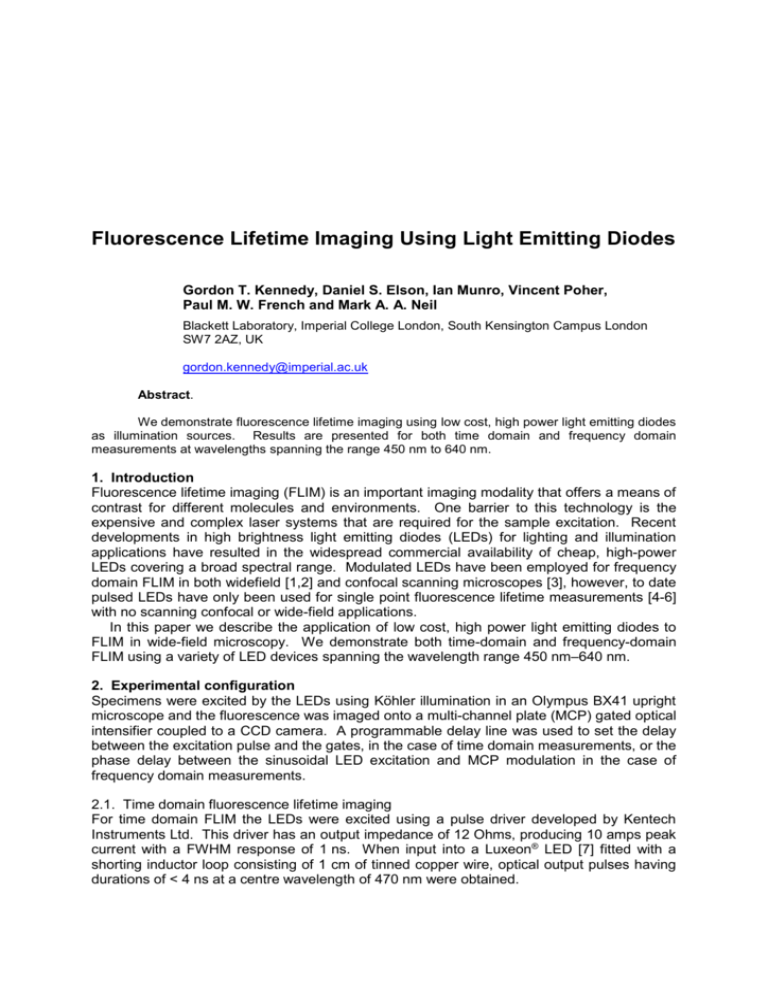

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Using Light Emitting Diodes Gordon T. Kennedy, Daniel S. Elson, Ian Munro, Vincent Poher, Paul M. W. French and Mark A. A. Neil Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus London SW7 2AZ, UK gordon.kennedy@imperial.ac.uk Abstract. We demonstrate fluorescence lifetime imaging using low cost, high power light emitting diodes as illumination sources. Results are presented for both time domain and frequency domain measurements at wavelengths spanning the range 450 nm to 640 nm. 1. Introduction Fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) is an important imaging modality that offers a means of contrast for different molecules and environments. One barrier to this technology is the expensive and complex laser systems that are required for the sample excitation. Recent developments in high brightness light emitting diodes (LEDs) for lighting and illumination applications have resulted in the widespread commercial availability of cheap, high-power LEDs covering a broad spectral range. Modulated LEDs have been employed for frequency domain FLIM in both widefield [1,2] and confocal scanning microscopes [3], however, to date pulsed LEDs have only been used for single point fluorescence lifetime measurements [4-6] with no scanning confocal or wide-field applications. In this paper we describe the application of low cost, high power light emitting diodes to FLIM in wide-field microscopy. We demonstrate both time-domain and frequency-domain FLIM using a variety of LED devices spanning the wavelength range 450 nm–640 nm. 2. Experimental configuration Specimens were excited by the LEDs using Köhler illumination in an Olympus BX41 upright microscope and the fluorescence was imaged onto a multi-channel plate (MCP) gated optical intensifier coupled to a CCD camera. A programmable delay line was used to set the delay between the excitation pulse and the gates, in the case of time domain measurements, or the phase delay between the sinusoidal LED excitation and MCP modulation in the case of frequency domain measurements. 2.1. Time domain fluorescence lifetime imaging For time domain FLIM the LEDs were excited using a pulse driver developed by Kentech Instruments Ltd. This driver has an output impedance of 12 Ohms, producing 10 amps peak current with a FWHM response of 1 ns. When input into a Luxeon® LED [7] fitted with a shorting inductor loop consisting of 1 cm of tinned copper wire, optical output pulses having durations of < 4 ns at a centre wavelength of 470 nm were obtained. A series 1 ns gate-width images were recorded and FLIM images were calculated by deconvolving the recorded instrumental response function (IRF) from the fluorescence profiles and using a non-linear least-squares fitting algorithm. Because the IRF was significantly longer using the LED than a pulsed laser source, we have characterised our fitting algorithm to assess its performance for different fluorescence lifetimes and fitting parameters. An ideal single exponential decay having Poissonian distributed noise was generated, and this was convolved with the recorded IRF. This was repeated for lifetimes ranging from 10 ps to 5 ns. The results of this fitting process indicate that even with such a large IRF, accurate (< 10 % standard deviation) lifetimes can be calculated down to 250 ps, although the error in the mean lifetime becomes significant at lifetimes of < 1 ns. FLIM images of stained convallaria and pollen grains are presented as Figure 1. The measured lifetimes are in agreement with previous results in the frequency domain, and time-domain FLIM with short pulsed laser excitation. Figure 1. FLIM images of (a) Stained convallaria, = 200-1200 ps (x40 magnification). (b) Stained pollen = 600-2000 ps (x20 magnification). 2.2. Multi-wavelength frequency domain fluorescence lifetime imaging It is possible to cheaply increase the available excitation wavelengths by using a number of different spectral outputs available from different LED devices. One novel device that has recently become available is the ACULEDTM from PerkinElmer [8]. Designed for lighting applications, these devices consist of four adjacent LED chips that emit in the red, green and blue spectral regions (centred at 634 nm, 518 nm and 456 nm respectively, with 2 identical green emitters). This chip was tested as an excitation source for frequency-domain FLIM by connecting dc and ac drive electronics through a bias tee, and the wavelength was selected through a manual switch. Each LED was driven at a low dc bias with 4 W of RF power superimposed at a frequency of 83.3 MHz (12 ns period). In order to efficiently couple the power into the LEDs at this frequency a simple tuned circuit comprising a series inductor and a parallel variable capacitor was employed. Standing wave ratios of <1.4 and modulation depths of greater than 50% were obtained for each diode. Standard Olympus filter cubes containing excitation, dichroic and emission filters were used (HQ:CY5 filter used for the red, HQ:CY3 for the green and a blue mercury filter for the blue). FLIM images were recorded with the gated optical intensifier using homodyne detection. Lifetimes were calculated from the demodulation of the fluorescence signal or the phase shift with respect to a reference sample (mirrored slide). Merged fluorescence lifetime and intensity images of triple-stained muntjac cells [9] taken using a x60 1.2 NA water immersion objective lens are presented as Figure 2 for the three excitation wavelengths. 3.5ns 0ns Figure 2. Merged frequency domain FLIM images for stained muntjac cells when excited with blue(left), green(centre) and red (right) LEDs. = 0 – 3.5 ns. Conclusion We have demonstrated fluorescence lifetime imaging using low cost light emitting diodes as the illumination source. Images were obtained in the time domain using pulsed illumination and in the frequency domain by direct modulation of the diode current. The low coherence of the LED sources combined with the even illumination field gives good image quality. Additionally, we demonstrate FLIM using three spatially multiplexed LEDs which, with the appropriate excitation and emission filter combinations, offers the possibility of rapid switching of excitation wavelengths during a single experiment. Acknowledgement This work was funded by the RCUK Basic Technology Research Programme, “A Thousand Micro-Emitters Per Square Millimetre: New Light on Organic Materials & Structures.” References [1] L. K. van Geest, and K. W. J. Stoop, FLIM a wide field fluorescence microscope, Lett. Pept. Sci. 10(5-6), 501-510 (2003). [2] C. Moser, T. Mayr, I. Klimant, Filter cubes with built-in ultrabright light-emitting diodes as exchangeable excitation light sources in fluorescence microscopy, J. Microsc. 222(2), 135-140 (2006). [3] P. Herman, B. P. Maliwal, H.-J. Lin, and J. R. Lakowicz, Frequency-domain fluorescence microscopy with the led as a light source, J. Microsc. 203(2), 176-181 (2001). [4] T. Araki, and H. Misawa, Light emitting diode-based nanosecond ultraviolet light source for fluorescence lifetime measurements, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 66(12), 5469-5472 (1995). [5] W. J. O'Hagen, M. McKenna, D. C. Sherrington, O. J. Rolinski, and D. J. S. Birch, MHz LED source for nanosecond fluorescence sensing, Meas. Sci. Technol. 13 84-91 (2002). [6] C. D. McGuinness, K. Sagoo, D. McLoskey, and D. J. S. Birch, A new sub-nanosecond led at 280 nm: Application to protein fluorescence, Meas. Sci. Technol. 15(11), L19-L22 (2004). [7] http://www.lumileds.com/ [8] http://optoelectronics.perkinelmer.com/content/datasheets/ACULED.pdf [9] FluoCells® #6, http://probes.invitrogen.com/media/pis/mp14780.pdf