Historical Overview

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act

As with the subject of race, the authors stress in Chapter 8,

Section A, that historical attitudes about women still

influence attitudes toward pregnant workers and working

mothers, and thus historical attitudes remain relevant in

the current legal analysis of discrimination based on

pregnancy and family responsibilities.

Taking a brief snapshot of the changing demographics from

1960 – 2008, i.e., that 71% of women with children under

age 18 worked outside the home, the authors emphasize

that this increase in the number of working women has not

diminished the perception of employment discrimination

based on pregnancy: That between 1997 and 2008 the

number of EEOC complaints rose 33%.

In Section B, the authors explain that, despite EEOC Guidelines, and the view of federal

circuit courts that discrimination based on pregnancy was a form of disparate treatment based

on sex, in violation of Title VII, the Supreme Court, in General Electric v. Gilbert, upheld an

employer’s right to exclude pregnancy from its short-term disability plan, because not all

women become pregnant. Revealing the gap in the Court’s view of discrimination, the

dissenters argued that the point of reference is whether the employer’s plan was as equally

comprehensive for women as men, and that since only women can become pregnant, the

employer’s exclusion of pregnancy from coverage constituted sex discrimination.

Congress responded to Gilbert by passing the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, 42 U.S.C.

Sec.2000e(k), which was interpreted by the Supreme Court in Newport News Shipbuilding &

Dry Dock Co. v. EEOC, to treat married male and female employees equally with regard to

health insurance coverage.

However, the authors note, despite the passage of the PDA and the Court’s interpretation of

the Act in Newport News, the Court continues to evolve its view of equality, and has held in

AT & T Corp. v. Hulteen (2009) that female employees and retirees whose post-PDA pensions

were lower than they would have been, as a consequence of pre-PDA calculations that gave

less credit to pregnancy leave than other disability leave (pregnancy being treated as personal

leave), were not the victims of pregnancy discrimination under Title VII. The authors note

that the Court’s rationale was based on its view of Title VII’s protection of bona fide seniority

systems to the extent that their disparate provisions were not intentionally discriminatory,

relying, over the dissent of Justice Ginsburg, on its decision in Gilbert, which Justice Ginsburg

would have expressly overruled.

Pregnancy is no different than other traits in revealing the continued judicial

struggle with the definition of “discrimination” to a degree not anticipated when

Title VII was enacted.

In Troupe v. May Department Stores, following a McDonnell Douglas-BurdineHicks analysis, the Seventh Circuit noted that Newport News overruled Gilbert,

but did not prevent an employer from subjecting pregnant employees to

termination for excessive absences for illness, so long as pregnant employees are

not treated differently from employees who are absent from work for other health

reasons. Judge Posner reasons that nothing in the PDA should be read to require

the employer’s tardiness or absent-from-work policies to treat pregnant employees

who suffer pregnancy-related illness more favorably than employees with other

health related absences from work. He explains that, to prove a violation of the

PDA, following the single motive-pretext analysis, Troupe would be required to

show ultimately that but for the fact of her pregnancy, she would not have been

terminated for excessive tardiness or absences. Although Troupe was terminated

one day prior to the beginning of her scheduled maternity leave, the court

required a showing of circumstances that would permit a factual inference that

the reason was related to her pregnancy. The Troupe rationale and other cases

(see Note 5) suggest that a PDA plaintiff may rely on traditional evidence, e.g., the

more favorable treatment of non-similar employees, comments of persons in the

decision-making process, and temporal proximity, but, even then, a causal

connection with the adverse action must be shown.

Consider the Supreme Court’s majority decision in California Federal Savings & Loan v.

Guerra (1987) that the PDA establishes minimal requires for nondiscrimination, and that a

California state law requiring employers to grant unpaid maternity leave and reinstatement

to pregnant workers is not pre-empted by the second clause of the PDA (requiring that women

workers affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions “shall be treated the

same for all employment-related purposes….as persons not so affected but similar in their

ability or inability to work”).

Three Justices dissented, arguing that the state law singled out pregnancy for “preferential

treatment,” in direct conflict with the PDA. Note the continued tension between equal

treatment and equal opportunity theory in the Court’s jurisprudence, and the view of some

Justices that nondiscrimination which requires any affirmative accommodation peculiar to an

otherwise protected trait violates Title VII. Consider how this view is applied in race and

gender cases, compared with the inherent nondiscrimination issues raised by religion cases

under Title VII and disability cases under the ADAAA.

On the subject of The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (a federal-state program mandating

minimal state standards), note the Supreme Court’s decision in Wimberly v. Labor &

Industrial Relations Commission (also 1987) that, while the PDA prohibited a state from

treating pregnancy unfavorably in the awarding of unemployment benefits, it does not require

a state to provide benefits to a pregnant worker who leaves work voluntarily and without good

cause “attributable to [her] work or to [her] employer.” To exempt pregnant employees from

this limitation on unemployment benefits would provide preferential treatment beyond the

parameters of the PDA.

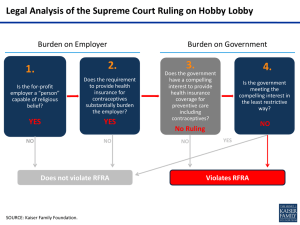

Focusing again on the principles of statutory construction or

interpretation, and administrative law, the authors note the

statutory language: That, under the PDA (42 U.S.C. Sec.

2000e(k), discrimination based on sex explicitly includes

pregnancy, childbirth, or “related medical conditions” – but the

statute does not define “related medical conditions.”

As a consequence the EEOC and the courts are left to define the

scope of rights under the PDA, and the authors present the

politically debated example of prescription contraceptives, as

discussed in Erickson v. Bartell Drug Company, a 2001 District

Court decision, in which plaintiff employees claimed that the

employer’s exclusion of prescription contraceptives under its

prescription benefit plan violated the PDA.

In Erickson, the District Court reaffirmed that Congress enacted the PDA to expand the scope of Title

VII’s protections beyond the limits imposed by the Supreme Court’s decision in Gilbert, and to

recognize the sex-based differences between men and women which require an employer to provide

“women-only” benefits or to incur additional expenses on behalf of women employees “in order to

treat the sexes the same.” The District Court emphasizes this legislative reversal of Gilbert.

The court noted that the employer’s plan was “facially neutral” as to included benefits, but violated

Title VII because it excluded a benefit which was uniquely designed for women. Citing Newport

News, the District Court explained that the Supreme Court’s concern is with the “relative

comprehensiveness” of coverage offered to men and women.

In broader interpretive terms, the court noted that discrimination based on any “sex-based

characteristic” (even if it is consistent regarding women employees and female spouses of male

employees) is sex discrimination under Title VII (citing the BFOQ defense as explained in Dothard v

Rawlinson and Johnson Controls): “The special or increased health care needs associated with a

woman’s unique sex-based characteristics must be met to the same extent, and on the same terms, as

other health care needs.” Thus, while an employer need not offer a prescription drug plan to its

employees, if it does offer such a plan, it must not exclude certain specific drugs or devices which are

used only by women.

The court rejected the employer’s argument that a woman’s control of her fertility is voluntary, and, in

any event, is not “pregnancy, childbirth or[a] related medical[ condition]” under the PDA and that the

issue in the case is thus one for the legislature.

The court’s reasoning in Erickson is relevant not only to the law of the case, but to

the ongoing political debate about an employer’s view of prescription

contraceptives:

The court explained that “the availability of affordable and effective

contraceptives [to prevent unwanted pregnancies] is of great importance to

the health of women and children because it can help to prevent a litany of

physical, emotional, economic, and social consequences … which carry

enormous costs for the mother, the child, and society as a whole” [Note the

politically charged debate over this observation in the ongoing debate about

affordable health care; note also the court’s reliance on legal scholarship, The

Office of Technology Assessment, empirical research, and the Supreme Court’s

observation in Stanton v. Stanton (1975) that the adverse consequences of

unwanted pregnancies interfere with a woman’s choice to “participate fully

and equally in the marketplace and the world of ideas”].

The court suggests explicitly that the employer’s attempt to distinguish

prescription contraceptives as uniquely “preventative” both begs the question,

and ignores the fact that other covered drugs are preventative.

In a significant observation about the role of the court when the plaintiffs’ rights

are based on statutory enactments, the District Court emphasized that (where the

statute is not explicit regarding the meaning of “related medical conditions”) the

overarching intent of the PDA was to overcome discrimination against women in

all aspects of employment, based on the flawed assumption that they would “get

pregnant and leave the workforce.” This perception, the court explained,

“relegated women to the role of marginal, temporary workers who had no hope of

promotion or equal opportunity regarding other terms and conditions of

employment.

The court also held that the traditional employer “cost” argument may not be

asserted to defend the exclusion of benefits that apply specifically to women

employees [Cf. the employer “cost” argument under the ADAAA].

Finally, the court notes that some deference should be given to EEOC guidance in

(even late-coming) cases of first impression which require a federal court to

interpret Title VII.

The authors note EEOC v. UPS (D. Minn. 2001), holding that the employer’s

exclusion of prescription contraceptives could also be challenged under disparate

impact theory, where the employer’s health plan covered the treatment of male

hormonal disorders, given the fact that prescription contraceptives are a form of

treatment of female hormonal disorders.

The 8th Circuit has disagreed with Erickson, holding in 2007 that contraception is not a

medical treatment that occurs when a woman becomes pregnant, and is thus not a medical

condition related to pregnancy. The dissenting judge challenged the majority’s restrictive

reading of the PDA, and reasoned that the issue under the operative clause of the PDA is

whether preventative health care coverage is offered equally to each gender.

Other courts have considered the operative cause of the PDA in cases raising the employer’s

exclusion of infertility treatments, and have held that such treatments are not “related to”

pregnancy or childbirth, the same rationale employed by the 8th Circuit case, supra, or that

reproductive capacity is common to both men and women and is not to be read into the PDA

as a new classification. See the cases cited in Chapter 8, Note 3, p. 430. Cf. Johnson Controls,

Chapter 7.

The authors note that state laws may explicitly require employers to provide coverage for

prescription contraceptives, citing New York’s Women’s Health and Wellness Act §3221(1)(16),

and noting that New York’s statute is intended to both protect women’s health and provide for

the equal treatment of women. Such laws may also extend protections such as the

accommodation for unpaid time and facilities for breastfeeding or the expression of breast

milk at the workplace. Note the proposal of a federal Breastfeeding Promotion Act in 2009.

Finally, note that while the PDA does not require an employer to pay for abortions (except

under certain conditions related to the mother’s or infant’s health), it does prohibit an

employer from refusing to hire a woman, or discharging a woman because she has had an

abortion. See 29 C.F.R. pt. 1604 (2009) and Doe v. C.A.R.S. (3rd Cir. 2008).

Citing empirical research and EEOC enforcement guidance the authors introduce the public

policy concern for the responsibilities associated with caregiving, and how this work-related

issue influences the need for expanded legislation and the protections afforded by Title VII,

the ADAAA and the FMLA.

The theory of Family Responsibilities Discrimination litigation is introduced in Chadwick v.

Wellpoint, Inc. (1st Cir. 2009), holding that an employer’s statements during the interview of a

candidate for internal promotion revealed stereotyping associated with the presumption that

women have a disproportionate responsibility for childcare that makes them less likely to

fulfill the responsibilities of their job.

The employer’s bias was specifically revealed in the explicit comments of interviewers

that it was not the quality of the candidate’s performance in her current position, but the

fact that she had childcare obligations (e.g., an 11 year-old son and triplets age 6) that the

female interviewers themselves felt were overwhelming, which caused the interviewers to

recommend another female candidate who had only two older children.

The appellate court cited the Supreme Court’s decision in Nevada Dep’t of Human Res. V.

Hibbs (2003) and other circuit court decisions recognizing stereotyping theory as

actionable when associated with caregiving responsibilities of working women, especially

when such concerns are explicitly mentioned to the employee by persons in the decisionmaking process.

Citing legal scholars, federal cases, and EEOC guidance, the authors note that this theory

does not create any new category of protection, but rather merely defines additional

circumstances under which Title VII is violated.

FMLA is emphasized in courses on Employment Law but is mentioned in

Employment Discrimination Law courses because it influences the interpretation

and application of Title VII and the ADAAA, and also facilitates the

understanding of the biases that inhibit equal employment opportunity based on

sex. FMLA subsumes only large employers and approximately 50% of workers do

not receive FMLA protections.

Under FMLA, covered employers are required to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid

leave to employees who have worked for at least one year, and to protect the

employee’s job re-entry into the same or similar job, under the following

circumstances:

The birth of the employee’s child and the need for immediate attendant child

care;

The placement of a child with the employee for adoption or foster care;

A serious health condition of the employee’s spouse, son, daughter, or parent

requiring the employee’s care; or

A serious health condition that makes the employee unable to perform the

requirements of her or his job.

Employers who already grant family leave may specify that FMLA leave is concurrent, and

may also provide that paid leave offered to the employee will be substituted for all or part of

FMLA leave.

Spouses employed by the same employer are entitled to a combined 12 weeks of FMLA leave.

The notes indicate that the scholarship related to FMLA is specific to the application of the

statute, and there continues to be a dialogue about the larger question of redefining the

relationship between work and family, and the issue of discrimination against males who

assume a primary child care role (noting that stereotypes about women’s domestic roles

reinforce parallel stereotypes presuming a lack of domestic responsibilities for men, and that

generally the U.S. lags behind other industrialized nations in providing family leave, e.g., paid

maternity and paternity leave).

Some Supreme Court justices see FMLA as “a social benefits or entitlements scheme” and not

an anti-discrimination statute, and circuit courts have compared it to the NLRA, FLSA and

ERISA. Moreover, the primary beneficiaries of FMLA are persons who can depend upon a

spouse wage earner; in this respect, FMLA offers little protection for many working class

women who are single-parents and work in the millions of American low-wage jobs, as well as

part-time or temporary jobs. Finally, as the Chapter notes indicate, in discrete circumstances,

the EEOC and courts may see FMLA, Title VII, and the ADAAA as creating possible

overlapping or conflicting issues that require unique statutory construction or judicial

deference, e.g., that EEOC regulations interpreting the ADA do not treat pregnancy,

unrelated to a physiological disorder, as an impairment.