What to Expect When Your Employee's Expecting

advertisement

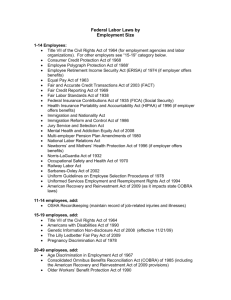

VIRGINIA CLE August 1, 2007 WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOUR EMPLOYEE IS EXPECTING Proving and Defending Pregnancy, Childbirth and Parental Leave Claims Employee Perspective Harris D. Butler, III Butler, Williams & Skilling, P.C. 100 Shockoe Slip, Fourth Floor Richmond, Virginia 23219 www.butlerwilliams.com hbutler@butlerwilliams.com Overview Since women entered the workforce in significant numbers they have faced subtle forms of differential treatment with the underlying premise that women were less productive or valuable employees than men. This was reflected in pay rates, assignments and promotional opportunities (reserving the key positions for the male ‘bread winners’). Female workers have been expected to endure not only lesser pay and benefits, but sexual harassment as a term or condition of simply receiving a pay check for a day’s work. Stereotypes regarding female workers’ abilities and limitations have persisted - none, perhaps, more universal than when the employee requires a temporary leave from work due to pregnancy or attempts to return to work after childbirth with an infant in the home. The federal constitution and some state constitutions’ equivalents to the U.S. CONST. Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments’ due process/equal protection clauses have long provided state and federal employees gender based job protections. Title VII to the 1964 Civil Rights Act first provided private sector employees protection against gender-based employment discrimination. The protections were specifically extended to pregnancy in the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. 1990 brought us the Americans with Disabilities Act which prohibits discrimination against both employees with disabilities and disabilities of those with whom the employee has a relationship or association, such as a parent, child or spouse. In 1993 the Family and Medical Leave Act provided an overlay of job protection upon return from periods of family or medical leave entitlements.1 Leave issues surrounding pregnancy and parental care remain in the forefront. EEOC filings on parental leave and family care issues are on the rise. Low wage earner caregivers face particular problems associated with stereotyping that deny them needed jobs. EEOC has noted that this form of discrimination falls 1 See EEOC Fact Sheet, The Family and Medical Leave Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (1995), http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/fmalada.html. 1 particularly hard on women of color, who often serve as not only the primary breadwinner, but the primary caregiver, for young and old family members. In May, 2007, the EEOC published its Guidance on Work/Family Balance issues entitled Unlawful Disparate Treatment of Workers with Caregiving Responsibilities2. This Guidance does not create new protections, but explains the existing protections for mothers and parents dealing with family leave issues provided by the intersections of various federal laws. EEOC Commissioner Stuart J. Ishimaru issued a statement regarding EEOC’s recent effort: “This guidance recognizes the connection between parenthood, especially motherhood, and employment discrimination. An employer may violate Title VII when it takes actions or limits opportunities for employees because of beliefs that the employer has about mothers and caregivers that are linked to sex.” Our culture has also changed. Colleges are graduating qualified women in greater quantities than their male peers. The stereotypical 1950’s image of the ‘perfect employee’ – the workaholic white male - has changed. Companies realize the value of work and personal life balance. According to the US Census Bureau, more women are returning to work after childbirth. Dads are now more involved with child rearing and family life. It is not a rarity for mom to return to work while dad stays home. As the internet and e-commerce explode, the ‘9 to 5’ format is becoming a thing of the past. E-commuting, home offices and ‘24/7’ access by PDA’s, laptops, wifi connections, and electronic advancements allow work to occur outside the four corners of the office. Logically and rationally, an employee who is committed to getting the job done can do so in far more ways than before. Women (and men) struggle to have it all – work time, family time and free time. Attitudes are difficult to change, however, and Congress has seen fit to provide certain statutory restrictions on an employer’s ability to use ‘at-will’ employment to penalize women or caregivers for their protected status. The new battleground involves how work in the 21st Century can get beyond the stereotypes of the past and balance an employer’s legitimate job needs against an employee’s rights to a tend to medical issues, raise a family and balance life outside the office. I. Pregnancy and Parental Leave Issues and Employment Protections A. Issues Range Run the Gamut From Application/Hire through Discharge and include: • Screening at application/hire for pregnancy/child-bearing years; • Selective treatment based on stereotyping; 2 www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/caregiving.html; see also the question and answer fact sheet at http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/qanda_caregiving.html. 2 • Selective application of leave policies/practices; • Forcing leave through fetal protection policies; • ‘Sex-plus’ discrimination – treatment of unwed moms, morality/appearance issues; • Maternity leave; • Seniority and job/work credit issues during periods of leave; • ‘Mommy-track’ treatment/practices; • When may pregnancy/family care issues legitimately support termination? • What are so closely related to pregnancy and childbirth to be protected – what about elective procedures related to infertility/fertility or abortion? • Creative uses of the blend of the FMLA, ADA and Title VII; • And practically speaking, how do you demonstrate employer knowledge of pregnancy based medically related conditions? B. The EEOC’s recent Guidance outlines an intersection of Title VII, ADA and FMLA and identified the following issues: • Treating male caregivers more favorably than female caregivers:: denying women with young children an employment opportunity that is available to men with young children. • Sex-based stereotyping of working women: • Reassigning a woman to less desirable projects based on the assumption that, as a new mother, she will be less committed to her job. • Reducing a female employee’s workload after she assumes full-time care of her niece and nephew based on the assumption that, as a female caregiver, she will not want to work overtime. • Subjective decisionmaking: Lowering subjective evaluations of a female employee’s work performance after she becomes the primary caregiver of her grandchildren, despite the absence of an actual decline in work performance. 3 • Assumptions about pregnant workers: Limiting a pregnant worker’s job duties based on pregnancy-related stereotypes. • Discrimination against working fathers: Denying a male caregiver leave to care for an infant under circumstances where such leave would be granted to a female caregiver. • Discrimination against women of color: Reassigning a Latina worker to a lower-paying position after she becomes pregnant. • Stereotyping based on association with an individual with a disability: Refusing to hire a worker who is a single parent of a child with a disability based on the assumption that caregiving responsibilities will make the worker unreliable. • Hostile work environment affecting caregivers: • Subjecting a female worker to severe or pervasive harassment because she is a mother of young children; • Subjecting a female worker to severe or pervasive harassment because she is pregnant or has taken maternity leave; and • Subjecting a worker to severe or pervasive harassment because his wife has a disability. C. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“Title VII”) 1. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e is the primary anti-discrimination statute prohibiting discrimination against employees or applicants due to race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It was dramatically revised by the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which amended the Act to allow for jury trials. Compensatory and punitive damages relief were also added. Selective or disparate treatment issues involving less favorable treatment of women are actionable under Title VII. 2. This includes sex-based stereotyping of females3; sex based stereotyping of female caregivers, assumptions of availability based on gender and caregiving; less favorable treatment as compared to other male employees generally, and less favorable treatment as compared to male caregivers. It may also include 3 See also stereotypes rejected by EEOC as a bona fide occupational qualifications (“BFOQ”) at 29 C.F.R. § 1604.2(a)(1)(ii): men are less capable than women of assembling intricate equipment; women are less capable of aggressive salesmanship. 4 the creation of a hostile environment based on one’s gender or race – and, as set out in the new EEOC Guidance, may be result from sex or race based hostility linked to caregiving responsibilities in violation of Title VII. 2. In addition to prohibiting the most common form of discrimination, known as disparate treatment, Title VII also prohibits discrimination due to facially neutral job requirements or regulations that have a disproportionate impact upon a protected group of employees. If a job requirement or regulation is determined to have a disproportionate impact on a protected group, it is unlawful unless the employer can demonstrate that the challenged practice is job-related for the specific position in question and is consistent with business necessity. See Scherr v. Woodland Sch. Community Consol. Dist. No. 50, 867 F.2d 974 (7th Cir. 1988), reh. denied (leave policies had disparate impact on women, rejecting argument that PDA did not allow disparate impact theory). 3. EEOC interpreted this to mean protection for pregnancy related disabilities. 29 C.F.R. § 1604.10(b) (1972) states: (b) Disabilities caused or contributed to by pregnancy, miscarriage, abortion, childbirth, and recovery therefrom are, for all job-related purposes, temporary disabilities and should be treated as such under any health or temporary disability insurance or sick leave plan available in connection with employment. Written and unwritten employment policies and practices involving matters such as commencement and duration of leave, the availability of extensions, the accrual of seniority and other benefits and privileges, reinstatement, and payment under any health or temporary or disability insurance or sick leave plan, formal or informal, shall be applied to disability due to pregnancy or childbirth on the same terms and conditions as they are applied to other temporary disabilities. 4. However, in a 1976 ruling involving a class based challenge to an employer’s disability plan excluding pregnancy from nonoccupational sickness coverage, the Supreme Court determined that pregnancy was distinguishable from Title VII’s gender protections. General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976), reh’g denied, 429 U.S. 1079 (1977). The Pregnancy 5 Discrimination Act legislatively corrected this to include such protection within Title VII. D. 5. EEOC charges must be filed within 300 days of the discriminatory event. Each discrete act of disparate treatment discrimination (pay, promotion, leave denial, selective treatment, demotion, termination or other terms or conditions of employment) should be included in a charge, or included in an amended charge, to avoid defenses that claims have not been properly preserved. See Amtrack v. Morgan, 536 U.S. 101 (2002) (each discrete act of discrimination must be supported by a timely charge of discrimination); Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 2007 U.S. Lexis 6295 (May 29, 2007) (Title VII gender compensation claim which merely challenged the present effects of past discrimination denied as not timely filed because EEOC charge was not filed at time of discriminatory act). Suit must be filed within 90 days of EEOC’s issuance of a Right to Sue letter. 6. Retaliation may include any action a reasonable employee would find materially adverse or that might have “dissuaded a reasonable worker from making or supporting a charge of discrimination.” Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White, 126 S. Ct. 2405, 2415 (2006). 7. Damage awards are subject to damage caps based on the size of the employer, to a maximum of $300,000 for compensatory and punitive damages (exclusive of front and back pay and benefits and attorneys fees/costs) for employers of over 500 employees (the applicable cap for employers of 15-100 employees is $50,000). The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 (“PDA”)4. 1. In reaction to the 1976 Gilbert ruling, Congress enacted an amendment to Title VII. The passage of the 1978 Pregnancy Discrimination Act, 42 U.S.C. 2000e(k) effectively overruled Gilbert. The PDA prohibits discrimination in treatment in regard to benefits and any differential treatment in all aspects of employment based on the condition of pregnancy. 2. Pregnancy, childbirth and related medical conditions may not be used to exclude women from the work force or to unreasonably 4 EEOC enacted Guidelines related to pregnancy and childbirth at 29 C.F.R. § 1604.10 with 37 Questions and Answers to provide further interpretation, attached. See “Questions and Answers on the Pregnancy Discrimination Act” 29 C.F.R. Part 1604 Appendix (1978). 6 restrict the terms or conditions of their employment in compensation, retention, advancement or benefits. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k) states: (k) The terms “because of sex” or “on the basis of sex” include, but are not limited to, because or on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions; and women affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions shall be treated the same for all employment-related purposes, including receipt of benefits under fringe benefit programs, as other persons not so affected but similar in their ability or inability to work, and nothing in section 703(h) of this title shall be interpreted to permit otherwise. (note- the text later excepts out health insurance benefits for abortion absent life endangerment to the mother or medical complications arising from abortion.) E. 3. Employers may not treat women differently because they are, or may become, pregnant. Disability related to pregnancy must be treated the same as non-pregnancy related temporary disabilities. 3. Benefit plans cannot deny contraceptive coverage if similar prescriptions are covered. Commission Decision on Coverage of Contraception (December 14, 2000).5 4. In that the Act is an amendment to Title VII, Title VII timelines for filing EEOC charges and damage caps apply to the PDA. The Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 (“ADA”)6 1. The ADA, 42 U.S.C. § 12201, et seq., provides protections to qualified individuals with disabilities as well as those who have relationships with disabled persons. This includes spouses, children and parents and the caregiving responsibilities associated with such situations. 2. In addition to the rare pregnancy related disability, disparate treatment based on stereotypical assumptions of an employee’s ability to satisfactorily perform job duties while also providing 5 See http://www.eeoc.gov/docs/decision-contraception.html See EEOC’s Questions and Answers About the Association Provision of the ADA at http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/association_ada.html. 6 7 care to a disabled spouse or child would fall within this protection. F. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (“FMLA”)7 1. The FMLA, 29 U.S.C. § 2601 et seq. provides employees with one year’s service (or at least 1250 hours during the previous 12 months) of employers with 50 or more employees of up to 12 weeks unpaid leave during a one-year period for: birth or adoption of a child; care of a son, daughter, spouse or parent of employee who has a serious medical condition; or a serious health condition that renders the employee incapable of performing the functions of his or her position. 2. An employee returning from FMLA leave is entitled to be placed in the same job or equivalent position, with the same pay, benefits, and working conditions (including privileges, prerequisites, and status). It must involve the same or substantially similar duties and responsibilities. 3. Certain “key” or “highly compensated” employees can be denied job restoration if the employer can demonstrate that it would cause “substantial and grievous economic injury” to operations. 4. The FMLA is similar to the statutory platform used for the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”) and Age Discrimination in Employment Act (:ADEA”). Relief is based on back pay and benefits and an equal liquidated damages amount upon a willful showing. A two year statute of limitations applies; three years for willful acts. EEOC does not have jurisdiction over FMLA claims. 5. Retaliation is expressly prohibited for any conduct taken in response to an employee’s exercise of FMLA rights or opposition to unlawful acts under the FMLA. 29 U.S.C. § 2615; Cline v Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 144 F.3d 294, 301 (4th Cir. 1998) (construing the anti-retaliation provisions of the FMLA, 29 U.S.C. § 2615(a)(2), as governed by Title VII standards). 6. In Nevada Dept. of Human Resources v. Hibbs, 528 U.S. 721 (2003), the Supreme Court held that Congress effectively abrogated states’ Eleventh Amendment immunity to monetary 7 See “Compliance Assistance – Family and Medical Leave Act” at http://www.dol.gov/esa/whd/fmla/ (U. S. Dept. of Labor web site). 8 damage awards in enacting the FMLA by making the statute’s family-leave provision specifically applicable to state employers. G. Constitutional Protections to Public Employees: Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment 1. The Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits government from treating one differently based on gender – the equal protection of the law. 2. Gender-based harassment violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Davis v. Passman, 442 U.S. 228, 234-35 (1979) the Court declared that individuals have a constitutional right under the Equal Protection Clause to be free from sex discrimination in public employment; See also Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 114 S. Ct. 367, 371 (1993) (Title VII application as to sexually hostile environment); Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., 523 U.S. 75, 81 (1998) (same sex harassment). 3. The Fourth Circuit has adopted Title VII standards for genderbased discrimination Equal Protection analyses. Beardsley v. Webb, 30 F.3d 524 (4th Cir. 1994). 4. 42 U.S.C. § 1983 is the statutory vehicle for damages claims and other relief against government and individual government officials acting unconstitutionally (Section 1983 claims). For governmental employers, this is a second level of exposure for gender based conduct which violates Title VII. EEOC does not have jurisdiction over these claims so there is no charge filing requirement. The Eleventh Amendment bars damages claims against the state itself but suit may be brought directly against either the official or municipality or other political subdivision. 5. Section 1983 allows for unlimited compensatory damages, and punitive damages are available (except from local governmental entities), as well as back pay, front pay, interest, attorneys’ fees, and other equitable relief, such as reinstatement, and the right to a jury trial. 6. The limitations period is borrowed from the most analogous state limitations period. Virginia Section 1983 claims have a two year 9 limitation period, which is much longer than the 300 day period applicable to filing EEOC charges on Title VII claims. 7. H. II. Municipalities and local governmental units cannot be sued on a respondeat superior theory for unconstitutional acts of their employees, but may be held liable for constitutional deprivations visited pursuant to a custom, pattern, practice or policy. Monell v. Dept. of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658 (1978). The Virginia Human Rights Act 1. The little used Virginia Human Rights Act, Va. Code §§ 2.1-714 to 2.1-725, prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, or disability. 2. The statute only applies to employers of 6-14 employees and has a limited private right of action to enforce its provisions. Claims must be filed within 180 days of the alleged discriminatory act. The Virginia Act coordinates and generally defers to federal antidiscrimination laws for larger employers. Special Pregnancy and Parental Leave Issues A. Can the Employer Force Leave or Terminate Due to Pregnancy? 1. Generally, the pregnant employee is free to continue working unless there is some demonstrable inability to perform “major functions” of the position. She should not be treated any differently than similarly situated non-pregnant employees regarding hire, employment status, leave or benefits. 29 C.F.R. Part 1604 App. 2. Such disparate treatment may not be justified under “benevolent” employer practices designed to protect the pregnant employee. Id. Employer attempts to dictate that pregnant employees may not work during the pregnancy, or forfeit employment opportunities due to the pregnancy, have not fared well in the courts. 3. Forced Leave Impermissible: Mandatory maternity leave unrelated to actual ability to work is impermissible. See Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. LaFleur; Cohen v. Chesterfield County Sch. Bd., 414 U.S. 632 (1974) (companion cases decided under Due Process Clause of Fourteenth Amendment). 10 4. Termination and Rehire Not Permitted. An employer policy requiring termination of pregnant employees, but allowing for their rehire after childbirth without loss of seniority, still violated the PDA. Even though the employer actually rehired most of the terminated women after childbirth, this was not a supportable ‘no-harm, no-foul’ application. EEOC v. Hacienda Hotel, 881 F. 2d 1504 (9th Cir. 1989). 5. “Fetal protection” policies – Employer policies affecting the working conditions of pregnant employees based on "fetal protection" considerations may also violate Title VII. In United Auto Workers International Union, UAW v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991), the Court held that a gender-based fetal protection policy excluding fertile women from all jobs involving exposure to lead (including exclusion from jobs which had the potential for promotion to higher risk positions) violated Title VII and were not defensible under either business necessity or BFOQ defenses; see EEOC Policy Statement on Reproductive and Fetal Hazards Under Title VII (Oct. 3, 1998); EEOC Policy Guide on UAW v. Johnson Controls (issued June 29, 1991). 6. Stereotyping as to perceived abilities of the pregnant employee: EEOC v. Old Dominion Sec. Corp., 41 FEP 612 (E.D. Va. 1986), aff’d in part and remanded in part, 816 F.2d 671 (4th Cir. 1987) held that an employee’s discharge from security duties during her 9th month of pregnancy violated the PDA. The employer’s asserted defense that she could no longer perform job due to pregnancy had no medical support. 7. Employer or Customer Perceptions: See EEOC .v. Red Baron Steak Houses, 47 FEP 49 (N.D. Cal. 1988) in which the Court held that a violation of the PDA where an employee was fired because it “did not look right for a pregnant woman to be waiting on tables.” 8. “Sex-plus” discrimination is involved where the employer imposes neutral criteria on members of one sex but not on members of the other sex. Philips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 592, 91 S. Ct. 496, 27 L.Ed.2d 613 (1971) (employer who refused to hire women with preschool children while hiring men with preschool children violated Title VII). a. ‘Sex plus’ analysis has also been applied in the unwed mother scenario (‘sex plus’ unmarried status). Ponton v. 11 Newport News Sch. Bd., 632 F. Supp. 1056 (E.D. Va. 1986) (district violated single pregnant teacher’s Title VII rights and constitutional right to privacy by giving her 3 options: (1) get married, (2) take a leave of absence, or (3) resign). b. B. See also Andrews v. Drew Mun. Separate Sch. Dist., 507 F.d 611 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. dismissed, 425 U.S. 559 (1976) (school district policy of firing unwed mothers violated Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of Fourteenth Amendment; noting impossibility of applying such a standard to unwed fathers). 9. Return to Work: EEOC Guidelines require employers to hold jobs open for women on pregnancy disability leave if it does so for other short-term disabilities. EEOC Q & A #9: “Q. Must an employer hold open the job of an employee who is absent on leave because she is temporarily disabled by pregnancy-related conditions? A: Unless the employee on leave has informed the employer that she does not intend to return to work, her job must be held open for her return on the same basis as jobs are held open for employees on sick or disability leave for other reasons.” 29 C.F.R. Part 1604 Appendix. 10. Failure to Hire/Rehire: An employer may not discriminate on the basis of the likelihood that an employee may become pregnant. Kocak v. Community Health Partners, 400 F.3d 466 (6th Cir. 2005) (employer violated Title VII by denying employment to employee who had quit because of a prior pregnancy; the fact that employee was not pregnant at time of application for rehire did not bar claim.) Can an Employer Alter Employment Terms, Conditions or Benefits to Pregnant Employees? 1. Selective Light Duty Denial. In Carrington v. Frank, 58 FEP 1796 (D. Neb. 1989) a pregnant female employee denied light duty established a prima facie PDA violation by comparison to similarly situated male injured in an off duty occurrence who requested and received light duty; but see Daugherty v. Genesis Health Ventures of Salisbury, Inc., 316 F.Supp. 2d 262 (D. Md. 2004) (employer not obligated to provide pregnant employee with light-duty when it did not provide light-duty to employees with physical restrictions except for work related injuries.) 12 2. Arbitrary Time Limits: An employer may not set fixed time limits for maternity leave that are not placed on other disability leaves. Maddox v. Grandview Care Center, 780 F.2d 987 (11th Cir. 1986, aff’g 607 F. Supp 1404 (M.D. Ga. 1985) (3 month limit on maternity leave not imposed on other disability leaves on a doctor’s recommendation violates Title VII on its face). 3. Marital Status: Benefits may not be based on marital status: See EEOC Guidelines, Question 13 “Q: May an employer limit disability benefits for pregnancy-related conditions to married employees? A. No”. 4. Seniority Accrual: Seniority for employees on maternity leave runs from the date of hire, not from date of return to work post pregnancy. EEOC Dec. No. 71-413, 3 FEP 233 (Nov. 5, 1970); Nashville Ga Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136 (1977) (policy denying accumulated seniority credit to employees for period of maternity leave had disparate impact on women in violation of Title VII). 5. Medically Related Conditions – Pregnancy related medical conditions are protected. These include infertility procedures and abortion related complications. Byrd v. Lakeshore Hosp., 30 F.3d 1380 (11th Cir. 1994) (pregnant employee terminated after took time off for pregnancy related medical condition, including physician prescribed bedrest after two near miscarriages, need not show comparator where sick leave benefits were made available through sick leave policy but pregnancy related medical leaves were excluded. “[I]t is a violation of the PDA for an employer to deny a pregnant employee the benefits commonly afforded temporarily disabled workers in similar positions, or to discharge a pregnant employee for using those benefits.” 30 F.3d at 1383-84. 6. Abortion - Most cases and the regulations support Title VII protection. See Turic v. Holland Hospitality, Inc., 842 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Mich. 1994), aff’d in pertinent part, 85 F. 3d 1211 (6th Cir. 1996), reh’g en banc denied (July 24, 1996) (citing Johnson Controls, the legislative history of the PDA and EEOC Guidelines as clearly indicating that a woman’s right to have an abortion is protected under Title VII). 13 C. Can the Employer discriminate against the Father? 1. 2. III. Daddy discrimination and “reverse” pregnancy claims –Title VII is violated when an employer terminates a husband for his wife’s pregnancy. a. In Nicol v. Imagematrix, Inc., 773 F. Supp. 802 (E.D. Va. 1991) a husband and wife, both Vice Presidents employed by the same employer, were terminated on the same day they told the President they were expecting a child. The husband alleged discrimination based on his wife’s pregnancy and on the basis of his sex. Finding Title VII standing for the husband, the court likened the situation to the termination of a white spouse discriminated against for marriage to a black spouse – the fact that the act was directed to a white employee did not change the fact that the discrimination was still based on the plaintiff’s race - even though the ‘root animus’ was an anti-black bias. The Court held that the PDA protected the father in this situation. b. The PDA also protects discrimination against males in the provision of pregnancy related benefits. See Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. v. EEOC, 462 U.S. 669 (1983) (PDA prevents against discrimination in the benefits provided to male employees’ dependents). Paternity leave – the FMLA protects parental leave whether the father or mother makes the leave request. While Title VII does not require employers to provide child care leave to fathers (no protected classification is involved), if offered it must be equally offered to men and women. The May, 2007 EEOC Enforcement Guidance: Unlawful Disparate Treatment of Workers with Caregiving Responsibilities A. Weaving Work/Family Issues and Caregiving Responsibilities into Existing Discrimination Law 1. Recognition of Title VII, PDA, FMLA and ADA applications to working mothers, single mothers, and caregivers for young and elderly family members. 2. Socio-economic realities that pregnant women and women of color often bear the brunt of stereotyped thinking as to how the woman can both perform job functions and care for others such 14 that Title VII race/gender, disability or pregnancy protections may reach to the non-protected ‘caregiver’ status. B. 3. In an extensively footnoted Enforcement Guidance supported by literature, research studies and case law, EEOC provides examples of how female caregivers can suffer unlawful Title VII disparate treatment when compared to male caregivers, when suffering unlawful gender based stereotyping and assumptions about future caregiving responsibilities and regarding pregnancy discrimination. 4. The Guidance also discusses discrimination against males, discrimination against women of color, stereotyping of employee caregivers for disabled persons with whom the employee has a relationship in violation of the ADA, hostile work environment liability for those targeted for protected status (race/gender/ADA) related to caregiving responsibilities and retaliation protections. 5. Mixed motive analysis applies to gender ‘caregiver’ claims. a. Under mixed motive analysis, a violation is shown even where a challenged employment decision was motivated both by a protected characteristic (such as sex) and a legitimate business reason. b. Where an employer can demonstrate that it would have reached the same decision in the absence of the illegal factor, the remedy for the violation may not include reinstatement, back pay or damages. Declaratory relief, non-reinstatement/ back pay injunctive relief and attorneys fees are available. Obviously, this would be a pyrrhic victory for the employee. Gender based Caregiver Liability 1. Employers may not deny opportunities based on assumptions that caregiving responsibilities will limit or interfere with job responsibilities. a. Employers may not rely on stereotypes of traditional gender roles for married women, new mothers or assumptions regarding future caregiving, childcare responsibilities, or the likelihood that an employee will become pregnant in considering employment opportunities. 15 b. It would violate Title VII and/or the PDA to assume that new mothers were less committed to their job or would work fewer hours. It would violate Title VII to deny part time or flexible work schedules to women based on sex stereotyped speculation as to how a “homemaker” would approach the job rather than based on specific work performance. 2. Discrimination against only a sub-group of the protected class, it is still actionable. Discrimination against working mothers violates Title VII even if the employer does not discriminate against childless women. 3. Even ‘benevolent’ stereotyping, believed to be in the employee’s best interest, is improper. Denial of a promotional opportunity based on the assumption that a working mother would not relocate to another city is illegal. 4. Caregiving does not provide a heightened status or protection – it is not a protected classification itself. Actual declines in work performance, even where due to caregiving responsibilities, are not protected against employer action. 5. Subjective Assessments of Work Performance May Not Legally Be Influenced by Stereotyping • Stereotyped perceptions that part time workers or caregiver employees are less dedicated may find their way to evaluations of performance. 6. • Such employees may be both thought of ‘bad mothers’ for committing time to work away from family and ‘bad workers’ for devoting time away from work to families. • Danger signs include abrupt changes in assessment that correlate to pregnancy or assumption of caregiver responsibilities, subjective assessments unaccompanied by objective criteria and changes in duties/assignments not readily explained by nondiscriminatory reasons. EEOC’s examples of sex-based Title VII violations include: • Interview questions to female (but not to male) caregivers about whether they were married, had young children, childcare and other caregiving responsibilities; • Derogatory remarks by decisionmakers regarding pregnancy, working mothers or female caregivers; 16 • • • • • • • C. D. Selectively negative treatment toward women soon after learning of their pregnancies; Selectively less favorable treatment, in the absence of declining work performance, toward women after assuming caregiving responsibilities; Steering of women with caregiver responsibilities to less pretigious or lower-paying jobs; Selectively favorable treatment given males with caregiver responsibilities as compared to women; Statistical disparities against pregnant workers or female caregivers; Employer deviations from policy in application to caregivers; and Pretextual, incredible reasons given for challenged actions. Pregnancy Specific Issues 1. Like Title VII, stereotyped assumptions about an employee’s commitment to work or ability to perform job functions are impermissible, even where the employer believes it is acting in the employee’s best interest. 2. Inquiries regarding pregnancy, followed by adverse job action, are presumed violative of the PDA. 3. Pregnancy testing may violate the medical testing prohibitions of the ADA. 4. Pregnant workers should be treated the same as similarly situated non-pregnant workers whose job performance is restricted because of conditions other than pregnancy. Discrimination Against Male Caregivers 1. Just as traditional female gender roles may be used to deny women employment opportunities, traditional male roles may be discriminatorily applied to men. 2. Gender stereotyping can result in disparate treatment against male employees. Men viewed a ‘bread winners’ and not caregivers may receive different treatment, harassment or less favorable leave or benefits than offered to female employees in violation of Title VII. Fathers working part time may be viewed 17 as ‘bad fathers’ by not providing for his family through full time work or ‘bad workers’ for lack of commitment to the job. 3. E. F. Granting childcare leave to females, but not to males would violate Title VII. (This is to be distinguished from pregnancy and childbirth related medical leave – which may be provided only to the pregnant woman.) Discrimination Against Women of Color 1. Recognizing that race or national origin undercurrents may be reflected in how stereotypes are applied, the Guidance discusses how women of color may face caregiver based discrimination. 2. An African American or Latino working mother or female caregiver may be provided less favorable treatment than her White counterpart. 3. The combination of race, gender and/or national origin bias and caregiver stereotyping assumptions can lead to Title VII, PDA, ADA and/or FMLA violations. Caregiver Stereotyping Discrimination in Violation of the ADA 1. An individual employee may have disabilities qualifying for ADA protection, although the normal pregnancy would not qualify. 2. However, caregivers may suffer discrimination for their association with one who is disabled. The ADA prohibits discrimination based on disability of one with whom the worker has a relationship or association, such as a child, spouse or parent. 3. Stereotyping based on assumptions of an employee’s ability to satisfactorily while also providing care to a relative or other individual with a disability could violate the ADA. Conclusion The recent EEOC Guidance only reaffirms that creative use of the intersection of the various employment discrimination laws may, though not formally, approach a sub-protected class for those providing care to family members. While the culture has changed, old stereotypes are hard to break. In advising employees, be alert to subtle forms of selective stereotyping violating gender, race, disability or family/medical leave protections. 18