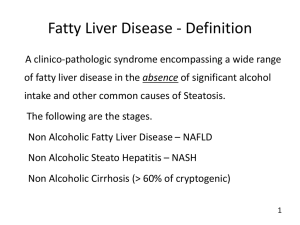

Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Presentation

advertisement

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and when to refer abnormal LFTs Dr Alexander Evans Consultant Hepatologist & Gastroenterologist Royal Berkshire Hospital NAFLD - The Problem! • Prevalence of abnormal LFTs in primary care is between 6 and 20%. • Abnormal LFTs may further represent a major burden to the NHS by way of investigations • The natural history of most liver diseases is many decades, and abnormal LFTs will not lead to serious liver disease in the short or medium term, and in many cases not even in the long term. BUT! • Mortality and Morbidity from liver disease is increasing • Prior to the development of end stage liver disease patients are usually asymptomatic • Primary care practitioners (PCPs) are thus commonly faced with the scenario of abnormal liver enzymes in patients in whom there are no clinical risks, signs or symptoms of liver disease. Current Practice – BSG commissioning report for jaundice and abnormal LFTs • “The decision of whom to refer to secondary care with abnormal liver enzymes and when is often arbitrary and has no relationship to the risk of serious disease being present.” • There is therefore a wide variation in thresholds for referral to secondary care • Advised development of local referral protocols • Commonest cause of asymptomatic abnormal LFTs is NAFLD Natural History and terminology of NAFLD ● Strongly associated with insulin resistance and considered the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH (2011). Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332(6037):1519-1523 NAFLD - Prevalence • Prevalence? – Biopsy diagnostic – Controversy of “normal ALT levels” – NAFLD spectrum of disease seen with normal LFTs from post-mortem studies. – Cryptogenic cirrhosis Prevalence studies for NAFLD Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM (2011). Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of NAFLD and NASH in adults. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 34:274-285 Prevalence studies for NAFLD Probably about 25% prevalence in the UK (and increasing reflecting increase in obesity and DM). Prevalence estimated to be at least 30% in USA 50% of obese children have NAFLD Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM (2011). Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of NAFLD and NASH in adults. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 34:274-285 Predisposing factors for progression of NAFLD 1) Obesity – Pt undergoing Bariatric surgery (90% steatosis, 30% NASH, 10% advanced fibrosis / cirrhosis) 2) Metabolic conditions – Type 2 DM – 66% will have US evidence of NAFLD – Polycystic ovarian syndrome – 50% 3) Age (may reflect longer standing undiagnosed NAFLD) 4) Gender M>F (?protective effect of oestrogen) 5) Ethnicity – Hispanics > Other white > African Americans 6) Genetics – PNPLA3 gene (Others include NCAN, GCKR, LYPLAL1) 7) Other (HCV/HIV) Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM (2011). Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of NAFLD and NASH in adults. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 34:274-285 NAFLD - Prognosis • Increased overall mortality compared to matched control populations. • Commonest cause of death in patients with NAFLD, NAFL and NASH is cardiovascular disease. • Increased liver-related mortality rate – increasingly common indication for liver transplantation (15-20%). Kawamura Y et al (2011). Large scale long term follow up study of Japanese patients with NAFLD for the onset of HCC. American Journal of Gastroenterology doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.327 Management of NAFLD in Primary Care ● History: Usually diagnosed on random blood tests performed on patients with unrelated symptoms. Higher threshold for screening at risk populations (e.g. Obesity / PCOS / Diabetics). Consider other risk factors for abnormal LFTs – Alcohol / viral hepatitis etc ● Examination: ?signs of chronic liver disease / BMI ● Investigations: FBC,U&E, LFTs, GGT, Fasting Cholesterol & Glucose, INR. • Consider performing liver screen if in doubt about diagnosis: HBV,HCV serology, Immunoglobulins, AI liver screen (ANA, AMA, Anti-LKM, Anti-SmA, Ferritin, αFP) - US abdomen: usually described as showing “diffuse increase in echogenicity of liver suggestive of fatty infiltration” Who to refer? Calculate NAFLD fibrosis score or fatty liver index! (Age, BMI, hyperglycaemia, plts, albumin, AST/ALT ratio). – AUROC 0.85 for advanced fibrosis. (There’s an app!!) www.nafldscore.com Dowman JK, Tomlinson JW, Newsome PN (2011). Systematic review: the diagnosis and staging of NAFLD and NASH. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 33: 525-540 Management of NAFLD in Primary Care • 1) Lifestyle changes – WEIGHT LOSS – – – – Explain diagnosis and set realistic target weight Nutritional counselling – refer to dietician Exercise – 3-4 times per week, expend 400 kcal per session Promrat et al 2010: Intensive lifestyle intervention (diet, exercise, behaviour modification) vs structured education alone. • Weight loss 9.3% vs 0.2% (p = 0.003) • Decrease in NAS 72% vs 30% (p=0.03) Younossi ZM (2008). Review article: current management of NAFLD and NASH. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 28: 2-12 Dowman JK, Armstrong MJ, Tomlinsomn JW, Newsome PN (2011). Current therapeutic strategies in NAFLD. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 13: 692-702 Medication for NAFLD • 1) Metformin • 2) Lipid-lowering agents (statins) – commonest cause of death is cardiovascular. – Reduced rate of HCC and improvement in LFTs – Statins are safe in liver disease!! (RCTs) • 3) Vitamin E • PIVENS trial 2010 – Improvement in NASH: 43% vs 19%, p=0.001 • Considered 1st line for pharmacotherapy of NASH (not in diabetic patients!) • 4) Thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone) – Improvement in liver histology whilst on drug but may relapse on stopping. Causes weight gain • 5) ?role for Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), DPP-4 inhibitors. • 6) Small proof of concept studies in Angiotensin receptor blockers / pentoxyfilline. Sanyal AJ et al (2010). Pioglitazone, Vitamin E or placebo for NASH. New England Journal of Medicine 362: 1675-85 Weight loss Interventions for NAFLD? 1) Orlistat • Zelber-Sagi et al 2006: Orlistat vs no orlistat – 6/12 treatment resulted in improved transaminases, steatosis on USS, and weight loss • Hussein et al 2007: Orlistat in NASH – 6/12 treatment improves histological steatosis, fibrosis and inflammation – 2) Gastric Band/Bypass • Mathurin et al.Gastroenterology 2009;137:532-540 – Prospective study – clinical, metabolic and liver histology at baseline, Yr 1 and Yr 5 after bariatric surgery. (56% Gastric Band, 21% Gastric bypass, Bilio-intestinal bypass 23%) • Significant Improvement in steatosis and hepatocyte ballooning, but equivocal as to whether fibrosis improves. • Cost neutral at 18 months When to refer abnormal LFTs • Refer? – Any patient with clinical, biochemical or radiological signs of liver cirrhosis. – Any patient in whom there is any doubt about the diagnosis of NAFLD. – Any patient whose LFTs fail to normalise with weight loss. – Any patient who despite above management options fails to lose weight, in whom a liver biopsy / Fibroscan is indicated (NAFLD fibrosis score / F.L.I.)