jdelgadillo_dcp_slides_dec12_faculty_of_addictions_0

advertisement

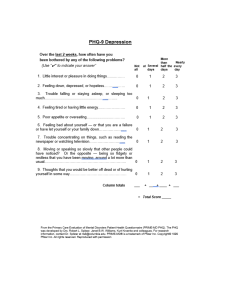

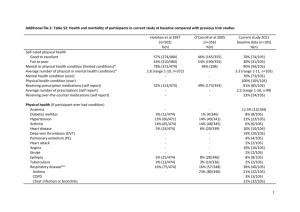

Mental health screening and outcome measurement in alcohol & drug users Jaime Delgadillo, PhD Leeds Primary Care Mental Health Service Presentation outline: 1. Overview of methodological challenges 2. CCAS study: validity and reliability of brief outcome measures 3. Implications for clinical practice Detecting and monitoring mental health problems: Methodological challenges Dual Diagnosis: epidemiology Depression & anxiety disorders commonly co-exist with addictions (Kessler et al, 1997; Merikangas et al, 1998; Farrell et al, 2001; Schifano et al, 2002) CMD in primary care = 5 - 20% (Katon & Schulberg, 1992; Kroenke et al, 2007) CMD in addictions treatment = 70 - 90% (Strathdee et al, 2002; Weaver et al, 2003) Adverse health & social consequences: Greater risk of suicide, more frequent and riskier substance use, cycle of relapse, homelessness, recurrent hospital admissions, treatment dropout, etc. (Harris & Barraclough, 1997; Havard et al, 2006; Bergman & Harris, 1985; Jeremy et al, 1992; Drake, 2007; Ford et al, 1991) Screening as usual? Observational studies in routine addiction treatment tend to use brief measures (BDI, HAM-D, BSI) and conventional cut-off scores, mostly reporting symptom improvement at 6 – 12 months (De Leon et al., 1973; Dorus and Senay, 1980; Kosten et al., 1990; Gossop et al., 2006) Two reviews describe over 20 mental health measures (SCL-90, GHQ, BDI, BAI, STAI, BPRS, K10, IES-R, etc) and recommend using these in addictions research (Dawe et al, 2002; Deady, 2009) Little or no consideration for validity / reliability of these questionnaires in addictions treatment Methodological challenges Several validation studies since the 70’s consistently report adequate sensitivity but poor specificity (Rounsaville et al, 1979; Hesselbrock et al, 1983; Willenbring, 1986; Weiss et al, 1989; Kush & Sowers, 1996; Coffey et al, 1998; Boothby & Durham, 1999; Hodgins et al, 2000; Buckley et al, 2001; Franken & Hendriks, 2001; Zimmerman et al, 2004; Luty & O’Gara, 2006; Rissmiller et al, 2006; Swartz & Lurigio, 2006; Dum et al, 2008; Lykke et al, 2008; Seignourel et al, 2008; Hepner et al, 2009; Holtzheimer et al, 2010; Lee & Jenner, 2010) Consequently, using brief measures and conventional cut-offs in alcohol & drug users may overestimate the prevalence of disorders (Keeler et al, 1979; Hesselbrock et al, 1983) Summary of key challenges 1. Using structured diagnostic interviews is seldom feasible due to cost, training, time, constraints. 2. Common symptoms associated with substance use interfere with the specificity of brief screening tools. This results in false positives. 3. Extreme measures of CMD symptoms (outliers) are likely to fluctuate. This means that observed symptom changes may be influenced by regression to the mean. 4. Observed changes in symptom scores may be due to measurement error. CCAS study: validity and reliability of brief outcome measures CCAS study: design Design Diagnostic validation study. Recruitment period: 1 year. Prospective cohort design, follow-up: 4-6 weeks. Participants 103 clients in routine methadone maintenance treatment in Leeds, excluding people with severe mental disorders. Measures CIS-R (Gold-standard diagnostic interview) PHQ-9 (Depression) GAD-7 (Anxiety disorders) TOP (Patterns of alcohol & drug use and self-rated mental health) Procedure Complete brief measures diagnostic interview re-test after 4 weeks CCAS study: sample CCAS study: results Table 1. Psychometric properties of brief screening tools for common mental disorders +PV – PV ICC 75 0.84 0.71 0.78 80 83 0.90 0.69 0.85 83 71 0.87 0.65 0.78 Cronbach’s Cut Sensitivity Specificity alpha off % % PHQ-9 0.84 ≥12 80 GAD-7 0.91 ≥8 ≤12 TOP (Delgadillo et al, 2011, 2012) CCAS study: results How stable are depression & anxiety symptoms after 4-6 weeks watchful wait? GAD-7 PHQ-9 Cut-off Cut-off ≥≥12 9 RCI ≥ 5 7 Implications for clinical practice Conclusions 1. Using cut-offs calibrated in clinical samples enhances specificity of brief screening tools. 2. Using RCI results in more conservative and reliable assessment of symptom change. 3. Approximately 25% of patients with a CMD reliably improve during a watchful wait period in routine MMT (ES = .30). Watchful wait can help to ‘screen out’ false positives and identify those who naturally improve. 4. Given the reliability of TOP, a step-wise screening / monitoring method may be feasible to implement in routine practice COBID trial: recruitment strategy Routine case-finding If: TOP <= 12 Then: PHQ-9 + GAD-7 If: PHQ-9 >= 12 Suitability screening interview & informed consent Random allocation BA in primary care Usual drugs treatment + guided self-help Thank you for listening Contact details: jaime.delgadillo@nhs.net