Analysis and critique of the responsibility to protect

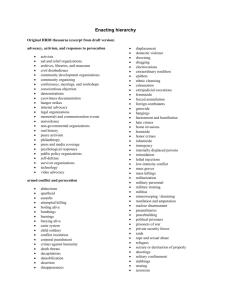

advertisement

Critique and Alternatives to the Responsibility to Protect by RICHARD JACKSON The National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies What is R2P? • The RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT ("R2P") is a new international security and human rights norm aimed at addressing the international community’s failure to prevent and stop genocides, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity • The norm was first suggested by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in 2001 • R2P was officially adopted by the UN in 2005 • It is supported by the INTERNATIONAL COALITION FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT (ICRtoP) which brings together NGOs from all regions of the world to strengthen normative consensus for RtoP, further the understanding of the norm, push for strengthened capacities to prevent and halt genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and mobilize NGOs to push for action to save lives in RtoP country-specific situations. The Responsibility to Protect stipulates: • The state bears the primary responsibility to protect its populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. This responsibility entails the prevention of such crimes and violations, including their incitement; • The international community has a responsibility to assist and encourage the state in fulfilling its protection obligations; • The international community has a responsibility to take appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian and other peaceful means to help protect populations from these crimes. • The international community must also be prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, in accordance with the UN Charter, on a case-by-case basis and in cooperation with relevant regional organizations, if a state fails to protect its populations or is in fact the perpetrator of crimes. • Such action may entail coercive measures, including the collective use of force, where appropriate, through the UN Security Council Proposed precautionary principles to be considered before authorizing military force: • • • • • • • Right intention Last resort Proportional means Reasonable prospects of success The “right authority” (UN Security Council) Just cause NOTE: States rejected including these principles in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document What’s wrong with R2P? • Its continuing unclear status in world politics – neither a law nor fully a norm; an aspiration? • It lacks clear triggers and thresholds for action • It is internally inconsistent – the preventive measures (such as arms control) undermine the reactive measures (the military capacity of states to intervene) • Its lack of widespread support – the Great Powers are suspicious of its obligations, while small states fear its use as justification for intervention and regime change • The danger (and record) of selectivity and vulnerability to Great Power manipulation – P5 self-interest and the veto • It is primarily reactive to crises – the preventive elements have remained largely inactive; the reaction paradigm is an obstacle to prevention (a logic and practice trap) • Existing (and stronger) international norms conflict with the R2P norm – for example, state sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs, the right of national self-defence What’s wrong with R2P? • It is state centric – the responsibility for protection lies with states and coalitions of states; the free-rider problem; in this formulation, states are both the problem and the solution • Ultimate reliance on violence – paradoxically, it reinforces the norm of employing violence to resolve crises; it implies continued military capabilities for states and the legitimacy of resort to force • It creates and maintains problematic distinctions between greater and lesser violence, good and bad violence, and worthy and unworthy victims • Status quo oriented – it leaves the global structures which create violence (including states) untouched; it balances too strongly towards state sovereignty • It’s dismal empirical record of failure and record of abuse • R2P is not the solution to the failures of the international community – it’s a Band-Aid on a fatally wounded system; R2P is a recognition that existing IHL has failed Questioning the paradigm of just war and humanitarian intervention • Just war theory is morally inconsistent in its separation of justice of war (jus ad bellum) and justice in war (jus in bello) • Just war elevates the political community (the nation state) to the highest good over the rights and survival of individuals • Just war creates two separate moral spheres (war versus peace) in which different moral standards apply • Just war raises intentions to a higher moral status than actions • Just war reinforces the very conditions which make war likely in the first place – separate nation-states who possess the right of self-defence Questioning the paradigm of just war and humanitarian intervention • Just war makes it easier for states to engage in wars – in practice, war is rarely the “last resort”; there are effective alternatives to violent resistance or enforcement • Just war has empirically failed to regulate the conduct of war • Just war is no longer relevant to modern warfare and insecurity, and there is no objective agreement on what constitutes “war” • There is no agreement on “right authority” for war • Empirically, modern weapons have made discrimination, proportionality and protection of civilians impossible • The implicit view that violence can be used as a morally neutral, and rational and predictable tool of policy (like a surgical scalpel) is theoretically and empirically incorrect Alternatives to R2P? • New thinking beyond the confines of the paradigm – long-term versus short-term; optimism for change; multiple levels of action and struggle for change rather than silver bullets; thinking preventively – breaking the cycle of reaction; thinking beyond the Weberian state • The success of nonviolence and nonviolent alternatives to use of force – preventive deployment; unarmed peacekeepers; policing; nonviolent accompaniment • Diplomacy, dialogue and mediation – the need for resources and investment to comparable levels of defence spending • Looking beyond track I to citizen-based diplomacy and initiatives • Research and training on nonviolent alternatives • Early warning and prevention rather than reaction – arms control, demilitarisation of politics, social justice • Justice and a global legal-normative human rights order – the ICC, regional justice mechanisms • Building resilience in local contexts