Ethos, Pathos, & Kairos

advertisement

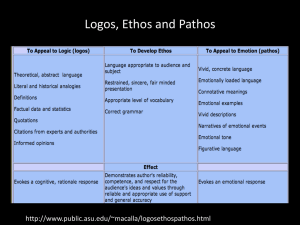

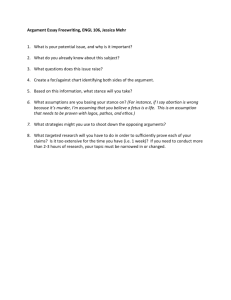

Mr. Baskin • We’ve already discussed the logical structure of arguments-the LOGOS. • We need to check out the other considerations as well. • It might be easy to think of these elements as some kind of recipe—a series of ingredients that, if added, will “make” your argument. • But, a more appropriate metaphor might be lights on a stage. • In theater, stage lighting is used to create varying effects—blue lights cast the stage in a sad pall, red lights reflect passion or rage, etc. • This is achieved through specific FILTERS that are placed over the lights. • If you slide in a PATHOS filter, and use concrete, vivid details and specific language, the resulting image will grab your audience’s sympathy and pull at their emotions. • If you use an ETHOS filter, you might alter your tone towards the audience, presenting yourself as a reasoned, intelligent, trustworthy person, changing your perceived image and strengthening your argument because your audience will want to believe what you say. • Yes, Allstate man. I believe in you! • And of course, if you point out facts or data—hard evidence, you will bring more LOGOS to bear in your lighting scheme. • The cool part is that this isn’t an ALL or NOTHING proposition. Most light filters are used partially, or overlapped, or changed out on the fly. • YOU decide how to “light” your stage. What appeals will work best? How can best motivate my readership to see things the way I do? Typically, it is a blend of all these elements that create compelling arguments. • You’re the director here. It’s up to you. • People should adopt a vegetarian diet because doing so will help prevent the cruelty to animals caused by factory farming. What type of argument is this? • If you are planning to eat chicken tonight, please consider how much that chicken suffered so that you could have a tender and juicy meal. Commercial growers cram the chickens so tightly together into cages that they never walk on their own legs, see sunshine, or flap their wings. In fact, their beaks must be cut off to keep them from pecking each other’s eyes out. One way to prevent such suffering is for more and more people to become vegetarians. And this? • People who eat meat are no better than sadists who torture other sentient creatures to enhance their own pleasure. Unless you enjoy sadistic tyranny over others, you have only one choice: become a vegetarian. And this one? • People committed to justice might consider the extent to which our love of eating meat requires the agony of animals. A visit to a modern chicken factory where chickens live their entire lives in tiny, darkened coops without room to spread their wings might raise doubts about our right to inflict such suffering on sentient creatures. Indeed, such a visit might persuade us that vegetarianism is a more just alternative. This one? • Each argument, while different, would probably suit a specific situation. • The only TRULY problematic one is #3. • Why? • Regardless, ETHOS, PATHOS, and LOGOS are different aspects of the same whole—each choice you make affects the appeals you make. Every word, every sentence, EVERYTHING. • While it may seem logical that previous experience could damage ETHOS (and it can), the Greeks felt that ETHOS came about through the speech itself. • Manner, delivery, tone, word choice, and arrangement of reasons create this effect. • How the writer handles alternative views (sympathetic, dismissive, hostile, etc.) also affect the audience and should be handled carefully. • So let us look at some tips for building ETHOS. • • • • First and best way to build credibility? BE CREDIBLE. Know what you are talking about. Argue from a strong base of understanding—have examples personal experiences, stats, data and more to make your case. • Doing your homework will command attention! • Demonstrating fairness and courtesy to alternative views is key. • Remember, REAL arguments only occur when people reasonably disagree with each other. • One caveat—there may be times when open scorn of an opposing view is effective and useful. HOWEVER, this is generally only when your audience is already on your side. • The BEST approach is to handle opposing views empathetically. • We’ve already covered this when we discussed Audience-Based reasons, but it’s worth restating— • By grounding your argument in shared values and assumptions, you demonstrate goodwill and enhance your image as a trustworthy person who respects their audience’s views. • Typically, this is a LOGOS concern—the better way to build a logical argument. • But, this is one place where the different aspects start to blend—where ETHOS and LOGOS start working together. • Who here HATES telemarketers? Those annoying jerks who call incessantly during our private, special time (when we aren’t doing anything except watching TV while texting and picking our noses in delightful anonymity)? • We all do, right? Right? • The next time an annoying sales call interrupts your dinner, think of my 71-year-old mother, LaVerne, who works as a part-time telemarketer to supplement her social security income. To those Americans who have signed up for the new national do-not-call list, my mother is a pest, a nuisance, an invader of privacy. To others, she s just another anonymous voice on the other end of the line. But to those who know her, she s someone struggling to make a buck, to feed herself and pay her utilities someone who personifies the great American way. What does this small story serve to do in the context of a larger argument about telemarketing? • This excerpt was from a New York Times op-ed piece titled “Don’t Hang Up, That’s My Mom Calling.” • Bobbi Buchanan—the writer—is trying to change our image of the telemarketer by connecting with our emotions about hardworking ‘Mericans just trying to make a buck to survive. • And it is SUPER-EFFECTIVE. • She continues: [LaVerne is] “hardworking, first generation American; the daughter of a Pittsburgh steelworker; survivor of the Great Depression; the widow of a World War II veteran; a mother of seven, grandmother of eight, greatgrandmother of three. . . .” • Arguers make pathetic appeals when they connect their claims to readers’ values, triggering their positive or negative emotions. • Examples: • When a pro-life proponent describes the process of abortion in graphic detail. • Proponents of women’s health in Africa may describe the horrific rape of a woman who was infected with HIV as a result. • Opponents of oil exploration in the arctic refuge might describe the beauty of the caribou calving grounds that would be destroyed by doing so. • Yes— • IF they intensify and deepen our response to an issue, not DIVERT attention from it. • Understanding isn’t JUST about reason and logic. • We’re emotional creatures, and using PATHOS can create nonlogical (but not nonrational) ways of knowing. • It can help us see the REAL STAKES at play in the issues, and pull them from the abstract to the actual. • The only time PATHOS becomes a problem is when it DIVERTS from the issue at hand. • Example: • A student argues that Professor Whosawhatsit should change their grade from a D to C so that they don’t lose their scholarship and return home in shame, causing their poor, disabled grandmother to weep uncontrollably for months and possibly die. • This appeal to PATHOS changes the focus from rationality to irrationality. • A weeping, nearly dead grandmother is a great reason for a student to study harder, but not for a professor to change a grade after the fact. • SEE HANDOUT! • KAIROS, as we have discussed, comes from the greek. • It differs from the Greek work for time—CHRONOS—the root of our words chronology and chronometer (watch). Chronos is a measure of time. • KAIROS—is all about sensing the opportune time for something through your psychological attentiveness. • To think KAIROTICALLY is to be attuned to the context of a situation in order to act in the right way at the right moment. • It’s the base runner who knows the moment to steal second, a person good at picking the right moment to speak rather than listen. • If you write a letter to the editor of a newspaper, you usually have a one- or two-day window before a current event becomes old news and is no longer interesting. An out-of-date letter will be rejected, not because it is poorly written or argued, but because it misses its kairotic moment. (Similar instances of lost timeliness occur in-class discussions: On how many occasions have you wanted to contribute an idea to class discussion, but the professor doesn’t acknowledge your raised hand? When you finally are called on, the kairotic moment has passed.) • A sociology major is writing a senior capstone paper for graduation. The due date for the paper is fixed, so the timing of the paper isn’t at issue. But kairos is still relevant. It urges the student to consider what is appropriate for such a paper. What is the right way to produce a sociology paper at this moment in the history of the discipline? Currently, what are leading-edge versus trailing-edge questions in sociology? What theorists are now in vogue? What research methods would most impress a judging committee? How would a good capstone paper written in 2010 differ from one written a decade earlier? • We’ll do this next week!