Lecture 5-Foster Birds and Symbols

advertisement

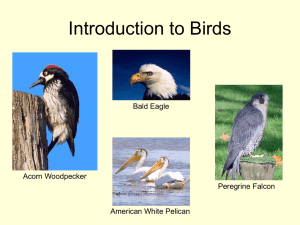

And Jungian Archetypes flight is freedom. Images of birds, feathers, and flying, all of which, while not referring to literal flight, evoke thoughts of metaphorical flight, of escape. Indeed, often in literature the freeing of the spirit is seen in terms of flight. Similarly, we speak of the soul as taking wing. The bird is an archetypal symbol of elevation, of the aspiration for rising to the absolute dimension of the sky, a constant and universal metaphor for the soul. In most archaic mythologies, migratory birds are incarnations of the soul of the dead person who departs for the afterworld. Birds have been considered “messengers of gods and all the manifestations of the spirits’ power assumed their wings.” Birds, wings and flight have all symbolized superior states of being. The connection between birds and the sky made the former be associated with angels and be attributed the angelic or solar language, which is nothing but poetry, a rhythmic language, meant to facilitate immersion into higher mental states. (Luc Benoist) The bird performs an initiating rite of passage, one of breaking through the space between the two worlds. The bird or the birds around the tree of life create an opening to the Garden of Eden; the connection with the afterworld allows the bird to foretell death. On the other hand, “birds symbolize thoughts and intuitions – between people and the soul there has always been a symbolic connection” (Aniela Jaffé). All characters who are as famous for their shape as for their behavior. Their shapes tell us something, and probably very different somethings, about them or other people in the story. Deformities project, hide, personal history, overcome Are deformities and scars therefore always significant? Perhaps not. Perhaps sometimes a scar is simply a scar, a short leg or a hunchback merely that. But more often than not physical markings by their very nature call attention to themselves and signify some psychological or thematic point the writer wants to make. After all, it’s easier to introduce characters without imperfections. You give a guy a limp in Chapter 2, he can’t go sprinting after the train in Chapter 24. So if a writer brings up a physical problem or handicap or deficiency, he probably means something by it. Here’s the problem with symbols: people expect them to mean something. Not just any something, but one something in particular. Exactly. Maximum. It doesn’t work like that. In general a symbol can’t be reduced to standing for only one thing. If it can, it’s not symbolism, it’s allegory. Allegories have one mission to accomplish – convey a certain message, George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) is popular among many readers precisely because it’s relatively easy to figure out what it all means. Orwell is desperate for us to get the point, not a point. Revolutions inevitably fail, he tells us, because those who come to power are corrupted by it and reject the values and principles they initially embraced. Symbols, though, generally don’t work so neatly. The more you exercise the symbolic imagination, the better and quicker it works. We tend to give writers all the credit, but reading is also an event of the imagination; our creativity, our inventiveness, encounters that of the writer, and in that meeting we puzzle out what she means, what we understand her to mean, what uses we can put her writing to. Imagination isn’t fantasy. That is to say, we can’t simply invent meaning without the writer, or if we can, we ought not to hold her to it. Rather, a reader’s imagination is the act of one creative intelligence engaging another. So engage that other creative intelligence. Listen to your instincts. Pay attention to what you feel about the text. It probably means something.