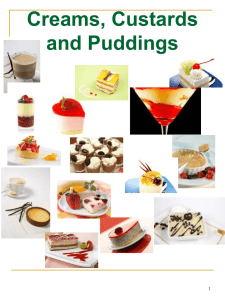

CUSTARDS

advertisement

BASICS FOR ONE OF THE PROFESSIONAL KITCHEN’S STAPLES What is a Custard? Custards are a mixture, generally cream based, that is thickened, gelled or set by the heat coagulation of egg proteins. They have both sweet and savory applications and the flavor profiles are limited only by the imagination, once we know how the ingredients interact. Is it a Crème Brulee for dessert or a Roasted Pepper flan as a dinner side? The choice is up to you. Stuff You Should Know! The Two Basic Custard types. STIRRED and BAKED STIRRED: Crème Anglaise, Pastry Cream, Sabayon, Lemon Curd, Various puddings and creams BAKED: Crème Caramel, Crème Brulee, Quiche, Pumpkin pie, Cheesecake, Bread Pudding Temperatures An undiluted egg will properly coagulate at 160 degrees. Diluted with milk, sugar or water , most custard sauces coagulate between 170 and 180 degrees. Stirred custards will generally curdle above 195 degrees. (many before 185 degrees) Baked custards usually set between 160 and 175 degrees. How do I test baked custards for doneness? Temperature Tips If Crème Anglaise curdles, can it be saved? Yes if not too excessive. Add 1 ounce of cold milk and process immediately with a stich blender, blender or processor, strain through a Chinoise. There will be some differences. The excess heat will cause a more egg flavor and a deeper yellow color. The saved sauce is typically thicker, not always a negative! Why do we use a water bath for baked custards? This allows for a steady temperature as water baths will rarely exceed a simmer 180-190 degrees. It prevents the outer edges from over baking before the center is set. Tempering Tempering is an important technique where we add two ingredients of different temperatures together. The goal is to combine without damage to either ingredient. If we were to add eggs directly to hot milk, they would instantly coagulate, leaving bits of cooked egg throughout. To avoid this, we add a small amount of the hot liquid to our eggs. Many think tempering is to raise the egg temperature, but it is really to dilute the egg without significantly raising the temperature. Once diluted, the eggs are less likely to be damaged as we add the remaining milk. The addition of sugar, or other room temperature ingredients also aides in this. “Cooked” Eggs When egg yolks and sugar set together in a bowl, and not immediately mixed, they will “cook”. This is a term used to describe the look of the yolks as they gel, appearing to cook. Sugars being hygroscopic, pull moisture from the yolk (yolks are only 50% water) drying them out. Without moisture, the proteins quickly aggregate, as if heat were applied, thus “cooked”. Avoid this by mixing the two immediately. The yolks will thicken but will not solidify. Factors Affecting Coagulation Proportion of egg: Dilution raises the coagulation temperature, thus slowing it down. Use of milk, sugar and creams further slows the coagulation. Rate of Cooking: The faster the rate of cooking, the less time for coagulation but when this takes place too quickly, the egg proteins don’t unfold properly and fail to gel or thicken as well. A lower, gentle heat will produce better products. Part of Egg used: Egg yolks coagulate at a higher temperature (150-160) than whites ( 140-150), making them less likely to weep and curdle. Remember that egg yolks are also emulsifiers and bond to fats. Also impacts taste and texture of finished products Sugar: Sugar helps prevent curdling by slowing protein coagulation and formation of egg structure. Excess sugar can cause coagulation to stop, and the baked good appears undercooked. Factors Affecting Coagulation Lipids: Fats, oils and emulsifiers interfere with coagulation of egg proteins, thus tenderizing custards, like they do baked goods. Acids: Acid speeds up egg coagulation, lowering the temperature of coagulation. This can come from lemon juice, or other fruit juice, raisins or other fruit or cultured dairy products. When using acidic ingredients, carefully monitor baking times. Starch: Increases the temperature of egg coagulation by interfering with the process. The starch protects the egg proteins, thus raising the temperature and as with pastry cream, allows, in fact it is a must to bring to a boil. Use of Starches Tip Be certain to fully cook your starch based custards. If they are not baked or brought to the boil the proper length of time, the starches will not properly gelatinize and Amylase that is present in egg yolks will not be inactivated, thus starches will be broken down into sugar and can liquefy pastry cream or a cream pie overnight. Crème Caramel 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Temperature: 325 Time: 50-60 minutes Ingredients Measure Water Sugar, granulated 2 fl. ozs. 5.75 ozs Milk Sugar Vanilla Extract Eggs, lightly beaten Egg Yolks 23 fl. ozs. 6 ozs. 2 tsp. 4 ea. 3 ea. Yield: 10 Ea. 4 oz. servings Procedure: Prepare the caramel: add the water and a small amount of first amount of sugar to a pan set over medium heat. Allow the sugar to melt. Add the remaining sugar in small increments, allowing it to melt before each new addition. Continue this process until all the sugar has been added. Cook the caramel to the desired color, remembering it will continue to cook off the heat a bit. Divide the caramel equally between ten 4 fl. oz. ramekins and swirl to coat bottoms. Place the ramekins into a deep baking dish and reserve. To prepare the custard, combine the milk and half of the second measure of sugar in a saucepan and bring to a simmer over medium heat, stirring gently with a wooden spoon. Remove from the heat and add vanilla. Return to the heat and bring milk to a boil. Blend the eggs and egg yolks, combine with the rest of the sugar, and temper the mixture into the hot milk. Strain the custard and ladle it into the prepared ramekins, filling them ¾ full. Bake the ramekins in a water bath at 325 until fully set, about an hour. Remove the custards from the water bath and wipe dry. Allow them to cool. Wrap each custard individually and refrigerate at least 24 hours before un-molding to serve. To unmold the custards, run a sharp knife around the rim with the blade towards the ramekin. Invert onto a plate and tap lightly to release. Crème Brulee Temperature: 325 Time: 20-25 minutes Ingredients Measure Heavy Cream Sugar, granulated Salt pinch 32 fl. ozs. 4 ozs Vanilla Bean Sugar 2 ozs. Egg yolks, beaten 1 ea. Yield: 10 ea. Standard Brulee 5.5 ozs. Procedure: Combine the cream, 4 ozs. of the sugar, and the salt and bring to a simmer over medium heat, stirring gently with a wooden spoon. Remove from heat. Split the vanilla bean, scrape the seeds from the pod, add both the pod and the scrapings to the pan, cover and let steep for 15 minutes. Return to the heat and bring to a boil. Combine the egg yolks and the rest of the sugar and temper the mixture into the hot cream. Strain the custard and ladle into 6- fl. oz. Crème Brulee ramekins, filling them ¾ full. Bake in a water bath at 325 until just set, 20-25 minutes. Remove the custards from the water bath and wipe the ramekins dry. Refrigerate until well chilled. To finish the crème Brulee, evenly coat the custard’s surface with a thin layer of sugar. Use a propane torch to caramelize the sugar. Lightly dust the surface with confectioner’s sugar and serve.