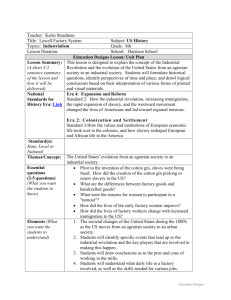

Chapter 8 Section 4 The Changing Workplace

advertisement

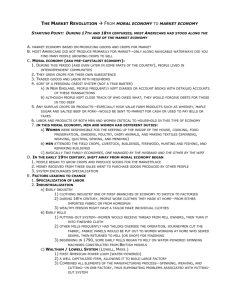

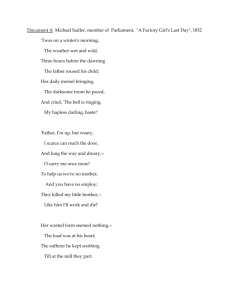

CHAPTER 8 SECTION 4 THE CHANGING WORKPLACE By Robbie Tanner INDUSTRY CHANGES WORK Rural Manufacturing Many Americans worked in a “cottage industry” system before the 1820’s in which people would get raw materials from factories and produce a final product at home in exchange for money and a new load of raw materials. This was the first step in the production of clothes and other textile goods until manufacturing and mass production came into play. INDUSTRY CHANGES WORK Early Factories Power looms replaced the cottage industry when entrepreneurs such as Francis Cabot Lowell, Patrick Johnson and Nathan Appleton began opening their weaving factories in Waltham, and later Lowell, MA. Having the entire process almost completely mechanized and all under one roof greatly reduced production time and cut prices of textile products drastically. By the 1830’s the Lowell and his partners owned eight factories across Massachusetts with over 6,000 employees total. INDUSTRY CHANGES WORK Early Factories At first it was only textiles, but other industries began to shift to factory production. Jobs that before had required skilled artisans to perform, as families could do for themselves, such as crafting furniture had shifted to mass production in factories. Skilled masters of craft then could not compete with the cheap prices of factory made goods, so were forced to move to urban areas and work in factories. The new factory machines allowed unskilled workers to perform tasks that used to require skilled masters to perform. FARM WORKER TO FACTORY WORKER The Lowell Mill The New England mill and factory workforce consisted almost entirely of young unmarried farm girls. Women were preferred over men to work in mills because factory owners would pay women less than men who performed similar jobs. By 1828 nine tenths of the New England factory workforce consisted of women, four out of five of these women were below the age of thirty. FARM WORKER TO FACTORY WORKER Conditions at Lowell Mill workers often worked twelve or more hours a day in poor conditions. Cotton dust made it difficult to breathe, and overseers sometimes nailed the windows shut to trap in humidity which they believed prevented the threads from snapping. Conditions at the mills continued to get worse as supervisors demanded a faster pace from their workers, between 1836 and 1850 Lowell owners tripled the number of spindles and looms but hired only 50 percent more workers to operate them. FARM WORKER TO FACTORY WORKER Strikes at Lowell In 1834 mill owners announced a 15% pay cut, in response over eight hundred mill workers went on strike demanding that their pay return to normal. Mill workers eventually prevailed and the workers returned to the mills accepting their 15% cut. In 1836 mill owners again announced a 12.5% pay cut, this time nearly twice as many workers went on strike. Once again the mill owners prevailed threatening to hire local women to replace the strikers. WORKERS SEEK BETTER CONDITIONS Immigration Increases European immigrations drastically rose in the 1830’s-1860’s. Over 3 million immigrants flocked to the U.S. which at the time had a population of only 20 million. The majority of these immigrants were German and Irish. Most of these immigrants strayed from the south as slavery limited their economic opportunity. WORKERS SEEK BETTER CONDITIONS A Second Wave Irish immigration soared in 1845-1854 when The Great Potato Famine wiped out their staple crop, and they were forced to relocate. Irish immigrants faced severe prejudice because of their religion, and because they were poor. Their willingness to work for any amount of money made them easy prey for mill employers looking for cheap labor. WORKERS SEEK BETTER CONDITIONS The National Trade’s Union During the 1830’s specific trade unions began to come together to form federations. In 1834, the largest of these unions, The National Trades Union, formed but lasted only until 1837. The movement of trades union faced challenges when bankers and mill owners formed unions of their own, and took a severe blow when the workers efforts to strike were ruled illegal. WORKERS SEEK BETTER CONDITIONS Court Backs Strikers In the case of Commonwealth v. Hunt, the court ruled the workers strikes legal, in that Boston’s journeymen shoemakers would act "in such a manner as best to sub serve their own interests.“ By 1860 although only 5,000 workers were participating in labor unions, upwards of 20,000 workers had participated in strikes.