The Changing Workplace

advertisement

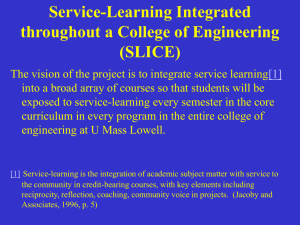

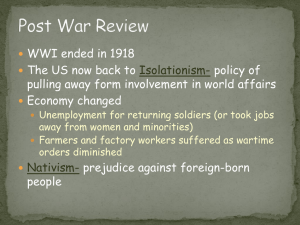

The Changing Workplace Chapter 8 Section 4 Industry Changes Work In the early 19th century almost all clothing was produced at home The move from home-based production to factory based production changed traditional families, communities, and employer/employee relationships Maggie Swietkowski Rural Manufacturing Until the 1820s, only the spinning of cotton into thread was mechanized widely The work was finished in a system called a cottage industry Manufacturers would give women the materials to finish the articles, when they finished making them they would send it back to the manufacturers, getting paid per piece https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dSjcHS_UZA (MS) Weaving factories opened in Waltham and Lowell, Massachusetts which replaced the cottage industry By mechanizing the entire process, production times and costs were reduced for producing textiles People like Patrick Jackson, Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell invested into the weaving factories, and by the 1830s they owned 8 factories with over 6,000 employees and a $6 million investment Early Factories Aside from textile factories, other areas of manufacture transitioned from few people to factories Artisans were skilled at creating items such as furniture and tools, different titles for the amount of experience one had A master was the most experienced, who was assisted by a skilled, hired journeyman, and an apprentice who was learning the trade • Artisans crafted their products until the 1820s when manufactures were able to produce interchangeable parts, which made their jobs unnecessary • As a result, the machines were able to do the work of highly trained artisans, employing many untrained workers MS Workers Seek Better Conditions The first general strike in Unites States was in 1835 , when Philadelphia coal workers struck for a 10-hour day and a wage increase. Although only 1 or 2 percent of U.S. workers were organized, there were dozens of strikes between 1830s and 1840s – many for higher wages and some for a shorter workday. Employers won most of the strikes because they could easily replace unskilled workers with strikebreakers who would work long hours with low wages Many strikebreakers were immigrants who fled poverty in Europe. SuAh Kim Immigration Increases Number of European immigrants increased dramatically in the United States between 1830 and 1860. 1845 – 1854 about 3 million immigrants were added to U.S. population, majority were German and Irish. Most immigrants avoided the South because slavery limited their economic opportunity. German immigrants gathered in the upper Mississippi Valley and in the Ohio Valley, where most of them became farmers and some became professionals, artisans, and shopkeepers in the Unites States. A Second Wave Between 1815 and 1844, nearly 1 million Irish immigrants settled in U.S. There was a blight that destroyed the peasants’ staple crop, potatoes, and led to a famine in Ireland. The Great Potato Famine killed as many as 1 million Irish people and pushed more people to immigrate to U.S. SK National Trades’ Union Journeymen formed trade unions specific to each trade. During 1830s, trade unions from different towns joined together to establish unions for trades like carpentry, shoemaking, weaving, printing, and comb making. In few cities, the trade cities united to form federations. In 1834, journeymen’s organizations from six industries formed the largest union called the National Trades’ Union, which lasted until 1837. The trade union movement was threatened by the unions formed by bankers and owners. Workers’ efforts to organized were interfered with court declaring strikes illegal. Court Backs Strikers In 1842, the Massachusetts Supreme Court supported workers’ right to strike in the case of Commonwealth v. Hunt. Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw declared that Boston’s journeymen boot makers could act “in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests.” By 1860, about 5000 workers were members of labor unions and 20,000 or more workers participated in strikes for improved working conditions and wages. SK Farm Worker to Factory Worker • By 1828, women made up nine-tenths of the work force in the New England mills, and four out of five of the women were not yet 30 years old. Armand Charkhutian The Lowell Mill Mill owners hired females because they could pay them lower wages than men who did similar jobs. Most female workers only stayed at Lowell for a couple of years and would eventually leave to pursue other work. AC Conditions at Lowell The work day started at 5a.m., at 12:30pm they would have dinner, and stay until 7:30. Heat, darkness, and poor ventilation were prominent in the mills. Overseers would nail windows shut to seal in the humidity that they believed would keep the threads from breaking. Between 1836 and 1850, Lowell owners tripled the numbers of spindles and looms but only hired 50% more workers and made a 15% wage cut. Strikes at Lowell Under the heading, “Union is power,” ordered a proclamation declaring that they would not return to work until their wages returned to what they previously were. Mill owners fired the strike leaders but the workers returned to their stations. In 1836, the workers went on strike again over a 12.5% pay cut and twice as many women participated as had two years earlier. Strikes at Lowell cont. In 1845, Sarah Bagley founded the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to petition the Massachusetts state legislature for a ten-hour work day. This proposal failed however the Lowell Association was able to help defeat a local legislature who opposed the bill AC