Child Labor Document Set

Warm-up: Photographs

Today we will start looking at impacts of industrialization. The following photographs get at one of the most striking impacts of the IR:

Child Labor

1) Watch as we scroll through the photographs. Some are from

England and some are from America

2) Choose one that stands out to you.

3) Make a title for it.

4) Write a couple sentences about why you chose it.

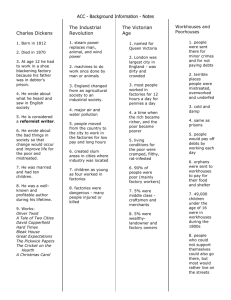

The political cartoon we just looked at addresses lots of problems created by the industrial revolution. Today we will talk about one:

Child Labor. As we look at these documents, think about how people might try to improve working and living conditions for children and for all factory workers.

When we study history, we can learn a lot from hearing the stories of people who have lived it. In this class before, you have been

“document detectives,” trying to understand the ideas and challenges in different time periods. The following documents are not by famous historical figures, but are the voices of ordinary people, many of them children – mostly younger than you. The responses below are about what you can learn from the document and why you think these documents were written or published.

Child Labor

Competition and demand led many factories to employ children. Many parents were unwilling to allow their children to work in the new new textile factories . To overcome this labor shortage factory owners had to find other ways of obtaining workers. One solution to the problem was to buy children from orphanages and workhouses. The children became known as pauper apprentices. This involved the children signing contracts that virtually made them the property of the factory owner.

In the following documents you will read about children working in textile mills and other new factories. Children also worked in other areas beyond heavy industry. Many children worked in mines. Four year olds were particularly good at fitting in small chimneys. Small children were sometimes used as scarecrows in farming fields, made to stand day and night to scare the crows.

Many children and young teenagers not attending school were rounded up on the street and forced to enlist in the British Navy, who in 1800 was busy fighting Napoleon.

There were many impacts of industrialization on workers. However, the IR changed the way we view both childhood and work.

Directions:

Read and discuss each document with your partner. Fill in the graphic organizer answering the response questions for each document.

The response questions are about what is in the document and why the document was written.

Big picture questions: What do these documents tell you about the working conditions in the Industrial Revolution?

Why might documents about children produce a public response?

Be ready to discuss as a class.

#1 Age of workers in cotton mills in Lancashire in 1833

Age Males Females under 11 246 155

11 - 16

17 - 21

22 - 26

27 - 31

32 - 36

1,169 1,123

736

612

355

215

1,240

780

295

100

37 - 41

42 - 46

47 - 51

52 - 56

57 - 61

168 81

98 38

88 23

41 4

28 3

RESPONSE 1: What does this chart tell you about who was working?

What does this chart tell you about who was NOT working? Possible effects of family life?

#2

Sarah Carpenter , interviewed in The Ashton Chronicle (23rd June, 1849)

My father was a glass blower. When I was eight years old my father died and our family had to go to the Bristol

Workhouse. My brother was sent from Bristol workhouse in the same way as many other children were - cart-loads at a time. My mother did not know where he was for two years. He was taken off in the dead of night without her knowledge, and the parish officers would never tell her where he was.

It was the mother of Joseph Russell who first found out where the children were, and told my mother. We set off together, my mother and I, we walked the whole way from Bristol to Cressbrook Mill in Derbyshire. We were many days on the road.

Mrs. Newton fondled over my mother when we arrived. My mother had brought her a present of little glass ornaments. She got these ornaments from some of the workmen, thinking they would be a very nice present to carry to the mistress at Cressbrook, for her kindness to my brother. My brother told me that Mrs. Newton's fondling was all a blind; but I was so young and foolish, and so glad to see him again; that I did not heed what he said, and could not be persuaded to leave him. They would not let me stay unless I would take the shilling binding money. I took the shilling and I was very proud of it.

They took me into the counting house and showed me a piece of paper with a red sealed horse on which they told me to touch, and then to make a cross, which I did. This meant I had to stay at Cressbrook Mill till I was twenty one.

Response #2:

What methods did factories use to find children and keep them working? Who do you think is the purpose of this interview in the Ashton Chronicle?

#3 Michael Armstrong, the Factory Boy (a novel written by Frances Trollope in 1840)

A little girl about seven years old, who job as scavenger, was to collect incessantly [non-stop] from the factory floor, the flying fragments of cotton that might impede [slow down] the work... while the hissing machinery passed over her, and when this is skillfully done, and the head, body, and the outstretched limbs carefully glued to the floor, the steady moving, but threatening mass, may pass and repass over the dizzy head and trembling body without touching it. But accidents frequently occur; and many are the flaxen locks, rudely torn from infant heads, in the process

David Rowland worked as a scavenger at a textile mill in Manchester. He was interviewed by Michael Sadler’s House of Commons

Committee on July 10, 1832.

Question: At what age did you commence [start] working in a cotton mill?

Answer: Just when I had turned six.

Question: What employment had you in a mill in the first instance?

Answer: That of a scavenger.

Question: Will you explain the nature of the work that a scavenger has to do?

Answer: The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught.

Elizabeth Bentley , interviewed by the Parliamentary Committee on 4th June, 1832.

I worked from five in the morning till nine at night. I lived two miles from the mill. We had no clock. If I had been too late at the mill, I would have been quartered. I mean that if I had been a quarter of an hour too late, a half an hour would have been taken off. I only got a penny an hour, and they would have taken a halfpenny.

Frank Forrest, Chapters in the Life of a Dundee Factory Boy (1850)

In reality there were no regular hours, masters and managers did with us as they liked. The clocks in the factories were often put forward in the morning and back at night. Though this was known amongst the hands, we were afraid to speak, and a workman then was afraid to carry a watch.

Response 3: What were the dangers of child labor? Be specific.

Why would Frances Trollope write a novel about a factory boy? Who is the intended audience of the novel?

#4

Primary Source : Sarah Carpenter was interviewed about her experiences in The Ashton Chronicle (23rd June,

1849)

There was an overlooker called William Hughes, who was put in his place whilst he was ill. He came up to me and asked me what my drawing frame was stopped for. I said I did not know because it was not me who had stopped it. A little boy that was on the other side had stopped it, but he was too frightened to say it was him. Hughes starting beating me with a stick, and when he had done I told him I would let my mother know. He then went out and fetched the master in to me. The master started beating me with a stick over the head till it was full of lumps and bled. My head was so bad that I could not sleep for a long time, and I never been a sound sleeper since.

We were always locked up out of mill hours, for fear any of us should run away. One day the door was left open.

Charlotte Smith, said she would be ringleader, if the rest would follow. She went out but no one followed her. The master found out about this and sent for her. There was a carving knife which he took and grasping her hair he cut if off close to the head. They were in the habit of cutting off the hair of all who were caught speaking to any of the lads. This head shaving was a dreadful punishment. We were more afraid of it than of any other, for girls are proud of their hair.

Response 4: What problems about child labor is this interview addressing?

What do you think the reaction might have been to this interview once it was published?

#5

Sir Samuel Smith worked as a doctor in Leeds. He was interviewed by Michael Sadler's House of Commons Committee on 16th July, 1832.

Question: Is not the labour in mills and factories "light and easy"?

Dr. Samuel Smith: It is often described as such, but I do not agree at all with that definition. The exertion required from them is considerable, and, in all the instances with which I am acquainted, the whole of their labour is performed in a standing position.

Question: What are the effects of this on the children?

Dr. Samuel Smith: Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way.

Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called "knock-knees" and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it.

Response #5:

What were lasting impacts of child labor? Why do you think Parliament would conduct interviews about child labor? Why would they interview a doctor?

#6

Response 6: What are these cartoons saying about child labor? Why might people protest child labor in cartoon form?

Reflection

Big picture questions: What do these documents tell you about how society viewed children during the industrial revolution? How is this different from today?

What are some specific ways people might demand changes in working conditions?