Statutory Interpretation - Teaching With Crump!

advertisement

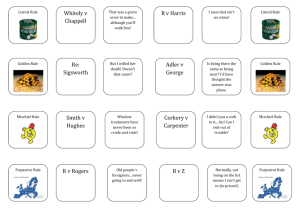

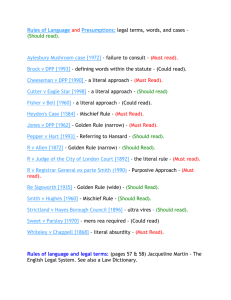

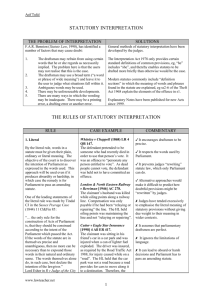

Statutory Interpretation Approaches to statutory interpretation Lesson Objectives • I will be able to explain the 4 approaches to statutory interpretation • I will be able to use cases to illustrate the rules of statutory interpretation A broad term: “type known as the pit bull terrier” in Dangerous Dogs Act 1991. What does this word mean? The need for Statutory Interpretation A drafting error made by the parliamentary Changes in the use of counsel who language: the meaning of drafted the a word might change, e.g. original bill, e.g. the meaning of as a bill is “passenger” in amended on its Cheeseman v DPP 1990 way through Parliament Ambiguity: if a word has two or more meanings which is the one that should be used? New developments: e.g. in technology. In Royal College of Nursing v DHSS 1981 “medical practitioner” now includes nurses for the purposes of abortion Introduction to statutory interpretation Statutory interpretation concerns the role of judges when trying to apply an Act of Parliament to an actual case. The wording of the Act may seem to be clear when it is drafted and checked by Parliament, but it may become problematic in the future. 75% of cases heard by the house of lords are concerned with statutory interpretation. 1. Presumption against a change in the common law 2. Presumption that mens rea is required in criminal cases Main presumptions of the court 3. Presumption that the Crown is not bound by any statute unless the statute expressly says so 4. Presumption that legislation does not apply retrospectively Presumptions are beyond the scope of this specification. The rules of interpretation There are two approaches to statutory interpretation: the literal approach and the purposive approach. There are also three main rules of statutory interpretation that judges use to decide a case: • the literal rule • the golden rule • the mischief rule 1. Literal rule – 2. Golden rule – the best interpretation of 3. Mischief rule words are ambiguous words can be chosen to – looks at the given their avoid an absurd result. The golden gap in law ordinary rule provides a kind of “escape route” prior to the grammatical when there is a problem with the literal Act and meaning. rule. interprets words to Whiteley v Allen: “Marry” = “go through a “suppress the Chappell: D ceremony of marriage”. Narrow mischief”. was found not version. guilty of Smith v Hughes: Re Sigsworth: Son not allowed to inherit “impersonating Prostitutes from mother because he murdered her. [someone] calling from a Wider version. entitled to house to men vote” when he in the streets impersonated a were dead man, as a soliciting “in dead person is a street”. not “entitled to vote”. Three rules of interpretation NB these three rules are all part of the literal approach: by using them judges are still trying to find/understand the meaning of the actual words in the statute. Even when using the mischief rule it is primarily the words of the statute that the judge is most concerned with. Literal rule The literal rule respects parliamentary sovereignty. The judges take the ordinary and natural meaning of the word and apply it, even if doing so creates an absurd result. Lord Esher said in 1892: ‘The court has nothing to do with the question of whether the legislature has committed an absurdity.’ Literal Approach The Literal Approach gives words their ordinary grammatical meaning R v Judge of the City of London Court: “If the words of an act are clear then you must follow them even though they lead to a manifest absurdity. The court has nothing to do with the question whether the legislature has committed an absurdity” LNER v Berriman: Not “relaying or repairing” track but oiling points (maintenance) • Leaves law-making to Parliament / respects democracy BUT assumes every Act will be perfectly drafted – Fisher v Bell • Makes law more certain BUT can lead to “unfair” decisions or absurd results – LNER v Berriman Pinner v Everett (1969) Lord Reid – “in determining the meaning of any words or phrase in statute, the first question to ask is always what is the natural and ordinary meaning of that word or phrase in its context of the statute.” Whiteley v Chappell (1868) Defendant voted in the name of a deceased person when the law stated that ‘any person is entitled to vote at an election’. Fisher v Bell (1961) This case concerned a flick knife displayed in a shop window. Lord Parker acquitted Bell under the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959, even though it was obvious that this was exactly the sort of behaviour that Parliament intended to stop. He justified his decision because the draftsmen knew the legal term ‘invitation to treat’ (which would have been applicable in this case) but failed to include it.To respect Parliament’s sovereignty he had to infer that they had left it out on purpose. Golden rule The golden rule is an extension of the literal rule. If the literal rule gives an absurd result, which is obviously not what Parliament intended, the judge should alter the words in the statute in order to produce a satisfactory result. Judges may used the narrow approach or the broad approach. R v Allen (1872) R v Allen is an example of the narrow approach of the golden rule. The wording of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 had to be given a different interpretation for the crime of bigamy, because the way it was written meant that the crime could never be committed. The court used the golden rule and held that ‘marry’ meant ‘to go through a marriage ceremony’. Adler v George (1964) Where there is only one literal meaning of a word or phrase, but to apply it would cause an absurdity, then under the broad approach the court will modify this meaning to avoid absurdity. Defendant charged under the Official Secrets Act 1920 which made it an offence to obstruct a member of the armed forces in the vicinity of a prohibited place. Defendant claimed he was ‘in’ not ‘in the vicinity of’. Court applied broad approach and applied the word ‘in’ to mean in the vicinity of and changed the meaning of the word. Mischief rule The mischief rule (or purposive approach) gives judges the most flexibility when deciding what ‘mischief’ Parliament intended to stop. It was established in Heydon’s Case (1584). When using this rule, a judge should consider what the common law was before the Act was passed, what the problem was with that law, and what the remedy was that Parliament was trying to provide. Fill in the gaps left by the Act. 1. What was the common law before the making of the Act? 2. What was the mischief and defect for which the common law did not provide? The mischief rule: Heydon’s case 1584 3. What was the remedy the Parliament hath resolved to cure the disease of the commonwealth? 4. The true reason of the remedy The court then interprets the Act in such a way as to cure the “mischief” Smith v Hughes (1960) The defendants were charged with ‘soliciting in a street or public place for the purposes of prostitution’ contrary to the Street Offences Act 1959. They were soliciting from upstairs windows. Lord Parker used the mischief rule to convict, as he believed that the ‘mischief’ that Parliament had intended to stop was people in the street being bothered by prostitutes. The Purposive Approach The mischief rule involves the court looking back to the common law position before the Act was passed to find the gap in the law that Parliament was trying to fill. The purposive approach focuses on what Parliament intended when passing the new law. It is a modern version of the mischief approach. The purposive approach has been used in: Pepper (Inspector of Taxes) v Hart (1993) – taxable benefits at private school Jones v Tower Boot Co. (1997) – racial abuse at work Purposive Approach The Purposive Approach looks for the purpose of Parliament and interprets words accordingly. Jones v Tower Boot Co: “In the course of employment” included racial harassment that happened at work even though it was not part of the work • Leads to justice in individual cases BUT makes law less certain • Fills in the gaps in the law BUT leads to judicial law-making as opposed to democratic law-making • Broad approach covers more situations BUT it is difficult to discover the intention of Parliament Trends towards the purposive approach • The literal approach is easily the more usual approach used by English courts • But use of the purposive approach is increasing: Most European countries use it The ECJ uses it in interpreting European Law (Marleasing), and therefore so must English courts The Human Rights Act 1998 says that legislation must be interpreted as far as possible to be compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. This will involve “inserting words” in effect into Acts to comply with this purpose: Offen; Mendoza v Ghiadan Bulmer Ltd v J Bollinger SA (1974) Lord Denning compared the different approaches of UK and EU law. When UK was bound by EU law, it is necessary to use the purposive approach. Denning stated “No longer must they examine the words in meticulous detail. No longer must they argue about the precise grammatical sense. They must look to the purpose or intent.” Page 42 Activities