Stat Interp PPT - Learn @ Coleg Gwent

advertisement

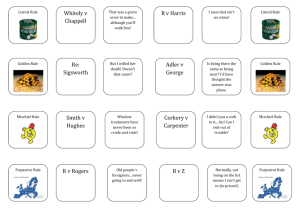

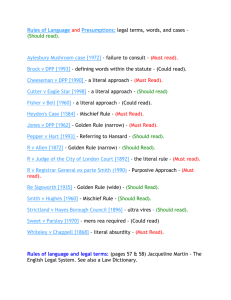

SOURCES OF LAW Statutory Interpretation involves the judges applying an Act of Parliament to an actual case. The wording of the Act may seem clear when it is drafted and checked by Parliament, but it may become problematic in the future. To know the difference between an intrinsic aid and an extrinsic aid Understand the purposive approach and how it relates to the three rules Understand the use of Hansard and when it can be used S.1 of the Act states that people with blonde and red hair should sit on the left side of the room. S.2 of the Act states that people with brown and black hair should sit on the right side of the room. In pairs discuss and list at least two problems of interpretation regarding this Act. There are two approaches: The literal approach and The purposive approach There are three rules of statutory interpretation: Literal rule Golden rule Mischief rule The judges take the plain, ordinary everyday meaning of the word or phrase and apply it to the case. The words are taken as read. The dictionary defines the meaning of literal as: taking words in their usual or most basic sense without metaphor or exaggeration. Parliament wanted to ban the use of flick knives. Under the Offensive Weapons Act (1959) it was an offence to “sell of offer for sale any flick knife”. In pairs read the case and apply the literal rule to this case. Remember using the literal rule the judge will take the plain, ordinary everyday meaning of the word or phrase. This rule is an extension of the literal rule. The judge will alter the words or interpretation in a statute so that it avoids an ‘absurd or repugnant result’. Judges may use the narrow approach or the broad approach. The narrow approach: Under this approach judges may choose between the possible meanings of a word or phrase. If there is only one meaning then this meaning must be followed. The broad approach: The words have one clear meaning, but following that meaning would lead to ‘a repugnant or absurd result’. Under s.57 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 bigamy is an offence, namely ‘anyone who marries another while still married’. Sigworth murdered his mum and under the Administration of Estates Act 1925 was due to inherit all her money. This was challenged by the rest of the family. The mischief rule was established in Heydon’s Case (1584). What was the law before the statute? What mischief was not adequately dealt with before the Act? What was the reason and remedy Parliament was hoping to obtain? Quite simply we ask ourselves what was the intention of Parliament when passing the law. The defendants were charged with ‘soliciting in a street or public place for the purposes of prostitution’ contrary to the Street Offences Act 1959. However, they were soliciting from an upstairs windows. Very similar to the mischief rule It goes beyond ‘filling the gaps’ in a statute It looks at what Parliament meant to achieve It looks for the purpose of the Act Literal Approach Literal Rule Purposive Approach Golden Rule Narrow Mischief Rule Broad Intrinsic Aids Extrinsic Aids Presumptions Latin Rules of Language These are sources within the Act (internal aids). To determine the meaning of a section of an Act of Parliament, the judge may wish to look at other sections in the Act: the definition section, preamble, and the long and short title. These are sources outside the Act (external aids): Dictionary Hansard Previous Acts of Parliament on the same topic Case law Interpretation Act 1978 Judges also make presumptions about the wording of a statute: the common law has not been changed unless the Act clearly states it a criminal offence usually requires a mens rea (guilty mind) and the law should not act retrospectively. Ejusdem Generis – of the same kind e.g. ‘motorbikes, cars and other vehicles’ Powell v Kempton Park Racecourse (1899) Expressio Unius Exclusio Alterius – the express mention of one thing excludes all others Tempest v Kilner (1846) makes a word draw others around it e.g. Noscitur a Sociis - meaning from ‘motorbike, care and fuel’. We can assume that the fuel is motor fuel. Beswick v Beswick (1968)