Statutory Construction

advertisement

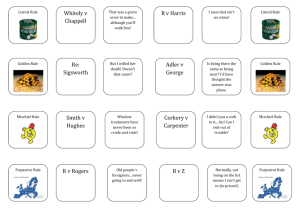

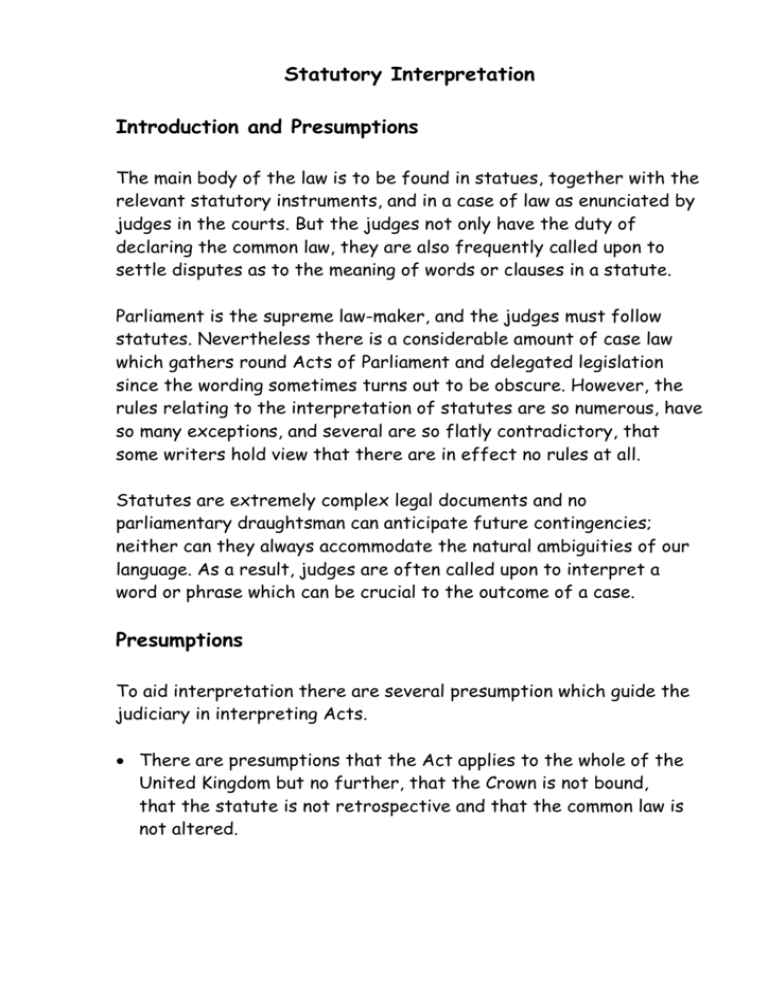

Statutory Interpretation Introduction and Presumptions The main body of the law is to be found in statues, together with the relevant statutory instruments, and in a case of law as enunciated by judges in the courts. But the judges not only have the duty of declaring the common law, they are also frequently called upon to settle disputes as to the meaning of words or clauses in a statute. Parliament is the supreme law-maker, and the judges must follow statutes. Nevertheless there is a considerable amount of case law which gathers round Acts of Parliament and delegated legislation since the wording sometimes turns out to be obscure. However, the rules relating to the interpretation of statutes are so numerous, have so many exceptions, and several are so flatly contradictory, that some writers hold view that there are in effect no rules at all. Statutes are extremely complex legal documents and no parliamentary draughtsman can anticipate future contingencies; neither can they always accommodate the natural ambiguities of our language. As a result, judges are often called upon to interpret a word or phrase which can be crucial to the outcome of a case. Presumptions To aid interpretation there are several presumption which guide the judiciary in interpreting Acts. There are presumptions that the Act applies to the whole of the United Kingdom but no further, that the Crown is not bound, that the statute is not retrospective and that the common law is not altered. A statute is resumed not to alter the existing law unless it expressly states that it does. When a statute deprives a person of property, there is a presumption that compensation will be paid. Unless so stated it is presumed that an Act does not interfere with rights over private property. Canons of Construction The rules, also known as canons of construction, are used to interpret statutes. Examples include: Literal Rule Golden Rule Mischief Rule Literal Rule This rule gives all the words in a statute their ordinary and natural meaning. Under this rule the literal meaning must be followed, even if the result is absurd. See: London & North Eastern Railway Co v Berriman 1946 Fisher v Bell 1961 Commentary The Literal rule has been the dominant rule, whereby the ordinary, plain, literal meaning of the word is adopted. Lord Esher stated in 1892 that “… if the words of an act are clear, you must follow them, even though they lead to manifest absurdity…” There are, however, a number of disadvantages in using this rule. It is often called the ‘dictionary rule’, but dictionary definitions can attribute several meanings to one word. It also restricts judicial creativity and holds back development of the law in keeping with changing social conditions. With the literal rule- it must be remembered that in extreme cases the statute may be carelessly drafted where certain words in isolation can have several meanings. The Law Commission 1969 was very critical of the literal rule as it assumed that Acts of Parliament were perfectly worded. The Law Commission in an instructive and provocative report on the subject of statutory interpretation said of this rule that ‘to place undue emphasis on the literal meaning of the words of a provision is to assume an unattainable perfection in draftsmanship’. The rule, when in operation, does not always achieve the obvious object and purpose of the statue. A classic example is Whiteley v Chappell (1868-9). In that case a statute concerned with electoral malpractices made it an offence to personate ‘any person entitled to vote’ at an election. The defendant was accused of personating a deceased voter and the court, using the literal rule, found that there was no offence. A dead person was not entitled to vote or do anything else for that matter. A deceased person did not exist and could therefore have no rights. It will be seen, however, that the literal rule produced in that case a result which was clearly contrary to the object of Parliament. Golden Rule The Golden Rule is an improvement on the above, as some attempt is made to put a word into its proper context. It is basically reverting to the literal rule but if a manifest absurdity results, judges can consider contextual alternatives, i.e. it is an extension or ‘offshoot’ of the literal rule. It is used by the courts where a statutory provision is capable of more than one literal meaning and leads the judge to select the one which avoids absurdity, or where a study of the statute as a whole reveals that the conclusion reached by applying the literal rule is contrary to the intensions of Parliament. Example: In Sigsworth (1935) the court decided that the Administration of Estates Act 1925, which provides for the distribution of the property of an intestate amongst his next of kin, did not confer a benefit upon the person (a son) who had murdered the intestate (his mother), even though the murderer was the intestate’s next of kin, for it is a general principle of law that no one profit from his own wrong. Lord Wensleydale commented on the use of the Golden rule in the following way: “The grammatical and ordinary sense of the words is to be adhered to unless that would lead to an absurdity or repugnancy or inconsistency with the rest of the instrument, in which case the grammatical or ordinary sense of the words may be modified so as to avoid such absurdity, repugnancy or inconsistency and no further’ - Lord Wensleydale in Grey v Pearson (1875). In Sweet v Parsley (1970), a schoolteacher was convicted for a strict liability offence because she had permitted her house to be used for cannabis smoking, even though she herself was abroad at the time and had no knowledge of the activity. The House of Lords held that the mens rea element should be read into the case, as Parliament would never have intended that an innocent person should ever be convicted. This illustrates how flexible the law can be by putting the alleged commission of an offence into its proper context. The Law Commission submitted a report in 1979, entitled ‘The Interpretation of Statutes’ , and supported the use of the Golden Rule, although it also recommended the use of an explanatory memorandum to clarify parliamentary intention. Mischief Rule Here the judge should interpret the statute in such a way as to put a stop to the problem that Parliament was addressing. This rule was laid down in Heydon’s Case in the 16th century and provides that judges should consider three factors: 1. What the law was before the statute was passed 2. What problem/ mischief the statute was trying to remedy 3. What remedy parliament was trying to provide. See Smith v Hughes (1960), Elliot v Grey (1960) and Royal College of Nursing v DHSS (1981). The mischief rule/mischief approach implies an ability and willingness on the part of the judge to look beyond the words of the statute itself. The Laws Commission in 1969 suggested that the ‘rules’ be relaxed and that greater focus should be placed on the Mischief Rule approach The European/Purposive approach EC law takes precedence over UK domestic law. If there is a conflict between EC and UK law, then EC law prevails; see Factortame (1990), Tachographs (1979) and Van Duyn v Home Office 1974. During his judicial career, Lord Denning was in the forefront of moves to establish a more purposive approach, aiming to produce decisions that put into practice the ‘spirit of the law’ even if that meant paying less that usual regard to the ‘letter of the law’. Denning stated his view in Factortame (1990): “We do not sit here to pull the language of Parliament apart to pieces and make nonsense of it ………… We sit here to find out the intention of Parliament and carry it out, and we do this better by filling in the gaps and making sense of the enactment than by opening it up to destructive analysis” Denning’s view contributed to the growth of a more purposive approach which gained ground in the last 20 years. Commentary: Blackstone also believed that the mischief/purposive approaches should prevail as, in his opinion, the ‘fairest and most rational method to interpret the will of the legislator is by exploring his intention at the time the law was made...’ Possibly the way forward is to again draw on the experience of continental law, where the judiciary are given much more freedom to interpret the law and often have training in the Parliamentary field to call upon. Denning and Lord Simon long campaigned for a more ‘open’ approach and favour the European model of statutory interpretation. Intrinsic Aids: The literacy rule and the golden rule both direct the judge to internal aids, Acts passed since the beginning of 1999 are provided with explanatory notes, published at the same time as the act Headings and subheadings used in an act can be a useful intrinsic aid External Aids: Dictionaries Law reports EU directives Treaties Since Pepper v Hart 1993 Hansard, which is a daily report of parliamentary debates. Using Hansard: Lord Denning’s argument, advanced in Davis V Johnson (1978), was that to ignore it was to “grope in the dark for the meaning of an act without switching on the light”. When such an obvious source of enlightenment was available, it was ridiculous to ignore it – in fact Lord Denning said after the case that he intended to continue to consult Hansard, but simply not say he was doing so! Using Hansard can be time consuming, because lawyers may spend too much time and attention to ministerial statements and so on at the expense of considering the language used in the act itself. Parliamentary intention is difficult if not impossible to pin down. Parliamentary debates usually reveal the views of only a few Members of Parliament and even then those words may need interpretation too. Rules of Language: Rules of language developed by lawyers are really little more than common sense although they are not always precisely applied. Examples include: Ejusdem generis: general words which follow specific ones are taken to include only things of the same kind. For example ‘dogs, cats and other animals’ the other animals would probably include other domestic animals. Noscitur a socis: a word draws meaning/ context from the other words around it. For example, if a statute included ‘cats, toys and food’ it would be reasonable to assume that the food is cat food.