ST file - Learn @ Coleg Gwent

advertisement

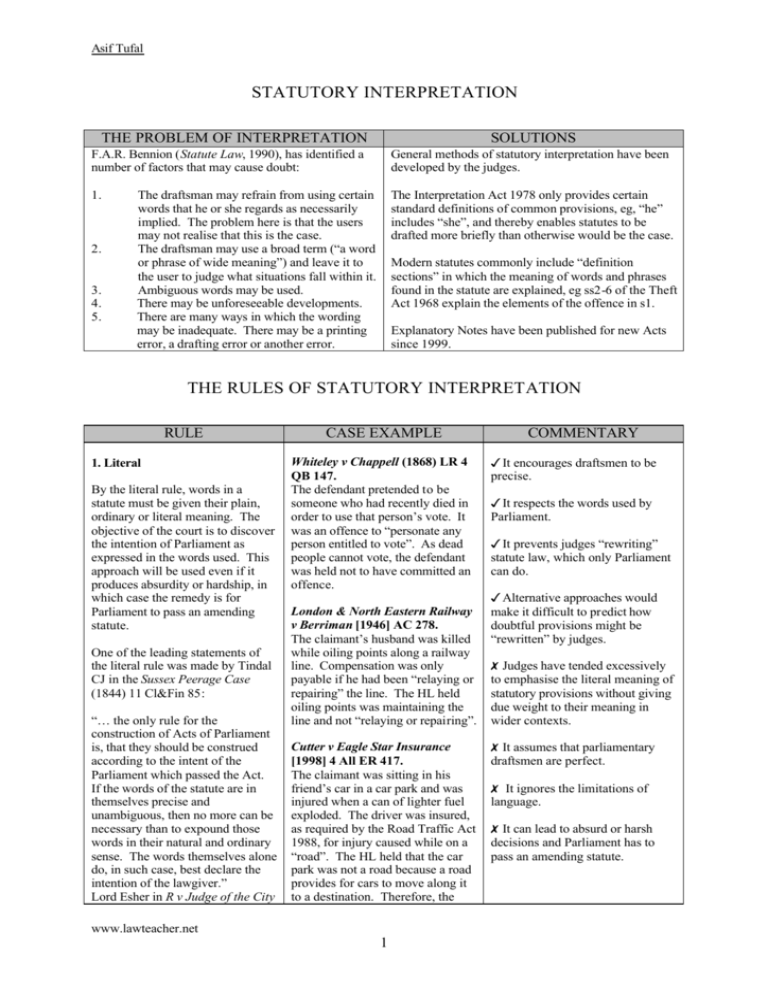

Asif Tufal STATUTORY INTERPRETATION THE PROBLEM OF INTERPRETATION SOLUTIONS F.A.R. Bennion (Statute Law, 1990), has identified a number of factors that may cause doubt: General methods of statutory interpretation have been developed by the judges. 1. The Interpretation Act 1978 only provides certain standard definitions of common provisions, eg, “he” includes “she”, and thereby enables statutes to be drafted more briefly than otherwise would be the case. 2. 3. 4. 5. The draftsman may refrain from using certain words that he or she regards as necessarily implied. The problem here is that the users may not realise that this is the case. The draftsman may use a broad term (“a word or phrase of wide meaning”) and leave it to the user to judge what situations fall within it. Ambiguous words may be used. There may be unforeseeable developments. There are many ways in which the wording may be inadequate. There may be a printing error, a drafting error or another error. Modern statutes commonly include “definition sections” in which the meaning of words and phrases found in the statute are explained, eg ss2-6 of the Theft Act 1968 explain the elements of the offence in s1. Explanatory Notes have been published for new Acts since 1999. THE RULES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION RULE 1. Literal By the literal rule, words in a statute must be given their plain, ordinary or literal meaning. The objective of the court is to discover the intention of Parliament as expressed in the words used. This approach will be used even if it produces absurdity or hardship, in which case the remedy is for Parliament to pass an amending statute. One of the leading statements of the literal rule was made by Tindal CJ in the Sussex Peerage Case (1844) 11 Cl&Fin 85: “… the only rule for the construction of Acts of Parliament is, that they should be construed according to the intent of the Parliament which passed the Act. If the words of the statute are in themselves precise and unambiguous, then no more can be necessary than to expound those words in their natural and ordinary sense. The words themselves alone do, in such case, best declare the intention of the lawgiver.” Lord Esher in R v Judge of the City CASE EXAMPLE Whiteley v Chappell (1868) LR 4 QB 147. The defendant pretended to be someone who had recently died in order to use that person’s vote. It was an offence to “personate any person entitled to vote”. As dead people cannot vote, the defendant was held not to have committed an offence. London & North Eastern Railway v Berriman [1946] AC 278. The claimant’s husband was killed while oiling points along a railway line. Compensation was only payable if he had been “relaying or repairing” the line. The HL held oiling points was maintaining the line and not “relaying or repairing”. Cutter v Eagle Star Insurance [1998] 4 All ER 417. The claimant was sitting in his friend’s car in a car park and was injured when a can of lighter fuel exploded. The driver was insured, as required by the Road Traffic Act 1988, for injury caused while on a “road”. The HL held that the car park was not a road because a road provides for cars to move along it to a destination. Therefore, the www.lawteacher.net 1 COMMENTARY 3It encourages draftsmen to be precise. 3It respects the words used by Parliament. 3It prevents judges “rewriting” statute law, which only Parliament can do. 3Alternative approaches would make it difficult to predict how doubtful provisions might be “rewritten” by judges. 7Judges have tended excessively to emphasise the literal meaning of statutory provisions without giving due weight to their meaning in wider contexts. 7It assumes that parliamentary draftsmen are perfect. 7 It ignores the limitations of language. 7It can lead to absurd or harsh decisions and Parliament has to pass an amending statute. Asif Tufal of London Court [1892] 1 QB 273 said: “If the words of an Act are clear then you must follow them even though they lead to a manifest absurdity. The court has nothing to do with the question whether the legislature has committed an absurdity.” 2. Golden The golden rule provides that if the words used are ambiguous the court should adopt an interpretation which avoids an absurd result. In Grey v Pearson (1857) 6 HL Cas 61, Lord Wensleydale said: “… the grammatical and ordinary sense of the words is to be adhered to, unless that would lead to some absurdity, or some repugnance or inconsistency with the rest of the instrument, in which case the grammatical and ordinary sense of the words may be modified, so as to avoid that absurdity and inconsistency, but no farther.” This became known as “Lord Wensleydale’s golden rule”. In its second, broader sense, the court may modify the reading of words in order to avoid a repugnant situation as in Re Sigsworth (1935). 3. Mischief The mischief rule is contained in Heydon's Case (1584) 3 Co Rep 7, and allows the court to look at the state of the former law in order to discover the mischief in it which the present statute was designed to remedy. The court stated that for the true interpretation of all statutes four things are to be considered: insurance company was not liable to pay out on the driver’s policy because the claimant had not been injured due to the use of the car on a “road”. R v Allen (1872) LR 1 CCR 367 The defendant was married and married again. It was an offence for a married person to “marry” again unless they were widowed or divorced. When caught the defendant argued that he did not commit this offence as the law regarded his second marriage as invalid. The court held that the word “marry” could also mean a person who “goes through a ceremony of marriage” and so the defendant was guilty. Re Sigsworth [1935] Ch 89. The defendant had murdered his mother. She did not have a will and he stood to inherit her estate as next of kin, by being her “issue”. The court applied the golden rule and held that “issue” would not be entitled to inherit where they had killed the deceased. 3It allows judges to avoid absurd or harsh results which would be produced by a literal reading. 3It allows judges to avoid repugnant situations, as in Re Sigsworth. 7There is clear way to test the existence of absurdity, inconsistency or inconvenience, or to measure their quality or extent. 7Judges can “rewrite” statute law, which only Parliament is allowed to do. Adler v George [1964] 2 QB 7. It was an offence to obstruct HM Forces “in the vicinity of ” a prohibited place. The defendants had obstructed HM Forces in a prohibited place (an army base) and argued that they were not liable. The court found them guilty as “in the vicinity of” meant near or in the place. Smith v Hughes (1960) 2 All ER 859. Six women had been charged with soliciting “in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution”. However, one woman had been on a balcony and others behind the windows of ground floor rooms. The court held they were guilty because the mischief aimed at was people being molested or solicited by prostitutes. www.lawteacher.net 2 4It allows judges to put into effect the remedy Parliament chose to cure a problem in the common law. 4It was developed at a time when: statutes were a minor source of law; drafting was not as precise as today and before Parliamentary supremacy was established. 7Judges can “rewrite” statute law, which only Parliament is allowed Asif Tufal 1st. What was the common law before the making of the Act. 2nd. What was the mischief and defect for which the common law did not provide. 3rd. What remedy Parliament resolved and appointed to c ure the disease. 4th. The true reason of the remedy; and then the function of the judge is to make such construction as shall supress the mischief and advance the remedy. Royal College of Nursing v DHSS [1981] 1 All ER 545. The Abortion Act 1967 allows abortions by “a registered medical practitioner”. Doctors carried out the first part of the procedure and the second was performed by nurses but without a doctor being present. The HL held (by 3-2) that this procedure was lawful because the mischief Parliament was trying to remedy was back street abortions performed by unqualified people. to do. 7It must be possible to discover the mischief in order for this rule to be used. Corkery v Carpenter [1951] 1 KB 102. A person could be arrested if found drunk in charge of a “carriage” on the highway. The defendant had been arrested for being drunk in charge of a bicycle on the highway. The court held that a bicycle was a “carriage” for the purposes of the Act because the mischief aimed at was drunken persons on the highway in charge of some form of transport, and so the defendant was properly arrested. DPP v Bull [1994] 4 All ER 411. A man had been charged with loitering or soliciting in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution. The court held that the term “prostitute” was limited to female prostitutes. The mischief the Street Offences Act 1959 was intended to remedy was a mischief created by women. 4. Purposive The purposive approach is one that will “promote the general legislative purpose underlying the provisions” (per Lord Denning MR in Notham v London Borough of Barnet [1978] 1 WLR 220). There will be a comparison of readings of the provision in question based on the literal or grammatical meaning of words with readings based on a purposive approach. In Pepper (Inspector of Taxes) v Hart [1993] AC 593, Lord BrowneWilkinson referred to “the purposive approach to construction now adopted by the courts in order to give effect to the true intentions Jones v Tower Boot Co Ltd [1997] 2 All ER 406. The complainant suffered racial abuse at work, which he claimed amounted to racial discrimination for which the employers were liable under s32 of the Race Relations Act 1976. The CA applied the purposive approach and held that the acts of discrimination were committed “in the course of employment”. Any other interpretation ran counter to the whole legislative scheme and underlying policy of s32. www.lawteacher.net 3 4It gives effect to the true intentions of Parliament. 7It can only be used if a judge can find Parliament’s intention in the statute or Parliamentary material. 7 Judges can “rewrite” statute law, which only Parliament is allowed to do. Asif Tufal of the legislature”. 5. Integrated Sir Rupert Cross, Statutory Interpretation (3rd ed, 1995), suggested that there was a unified approach to interpretation: (i) the judge begins by using the grammatical and ordinary or technical meaning of the context of the statute; (ii) if this produces an absurd result then the judge may apply any secondary meaning possible; (iii) the judge may imply words into the statute or alter or ignore words to prevent a provision from being unintelligible, unworkable or absurd; and (iv) in applying these rules the judge may resort to various aids and presumptions. THE RULES OF LANGUAGE RULE CASE EXAMPLE Powell v Kempton Park Racecourse [1899] AC 143. It was an offence to use a “house, office, room or other place for betting”. The defendant was operating from a place outdoors. The court held that “other place” had to refer to other indoor places because the words in the list were indoor places and so he was not guilty. 1. Ejusdem generis (of the same kind) General words f ollowing particular words will be interpreted in the light of the particular ones. Muir v Keay (1875) LR 10 QB 594. All houses kept open at night for “public refreshment, resort and entertainment” had to be licensed. The defendant argued that his café did not need a licence because he did not provide entertainment. The court held that “entertainment” did not mean musical entertainment but the reception and accommodation of people, so the defendant was guilty. 2. Noscitur a sociis (known from associates) A word will be interpreted in the context of surrounding words. Tempest v Kilner (1846) 3 CB 249. A statute required that contracts for the sale of “goods, wares and merchandise” of £10 or more had to be evidenced in writing. The court had to decide if this applied to a contract for the sale of stocks and shares. The court held that the statute did not apply because stocks and shares were not mentioned. 3. Expressio unius est exclusio alterius (the express mention of one thing is the exclusion of another) The express mention of things in a list excludes those things not mentioned. www.lawteacher.net 4 Asif Tufal INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL AIDS TO INTERPRETATION There is a wide range of material that may be considered by a judge when interpreting statutes. Some of these aids may be found within the statute in question, others are external to the statute. INTERNAL EXTERNAL 1. Other enacting words An examination of the whole of a statute, or relevant Parts, may indicate the overall purpose of the legislation. It may show that a particular interpretation of that provision will lead to absurdity when taken with another section. 1. Dictionaries and other literary sources Dictionaries are commonly consulted as a guide to the meaning of statutory words. Textbooks may also be consulted. 2. Practice The practice followed in the past may be a guide to interpretation. For example, the practice of eminent conveyancers where the technical meaning of a word or phrase used in conveyancing is in issue. 2. Long Title The long title should be read as part of the context, “as the plainest of all the guides to the general objectives of a statute” (per Lord Simon in The Black-Clawson Case [1975]). 3. Other Statutes in Pari Materia Related statutes dealing with the same subject matter as the provision in question may be considered both as part of the context and to resolve ambiguities. A statute may provide expressly that it should be read as one with an earlier statute(s). 3. Preamble When there is a preamble it is will generally state the mischief to be remedied and the scope of the Act. It is therefore clearly permissible to use it as an aid to construing the enacting provisions. 4. Official Reports Legislation may be preceded by a report of a Royal Commission, the Law Commissions or some other official advisory committee. These reports may be considered as evidence of the pre-existing state of the law and the “mischief” with which the legislation was intended to deal. However, it has been held that the recommendations contained in them may not be regarded as evidence of Parliamentary intention as Parliament may not have accepted the recommendations and acted upon them (The BlackClawson Case [1975] AC 591). 4. Short Title There is some question whether the short title should be used to resolve doubt. 5. Headings, side -notes and punctuation Headings, side-notes and punctuation may be considered as part of the context. 5. Treaties and International Conventions There is a presumption that Parliament does not legislate in such a way that the UK would be in breach of its international obligations. 6. Parliamentary Materials/Hansard In Pepper (Inspector of Taxes) v Hart [1993] AC 593, the House of Lords relaxed the general prohibition (in Davis v Johnson [1979] AC 264) that a court may not refer to Parliamentary materials, such as reports of debates in the House and in committee (Hansard) and the explanatory memoranda attached to Bills, when interpreting statutes. They may now be used where: (a) legislation is ambiguous or obscure, or leads to an absurdity; (b) the material relied on consists of one or more statements by a minister or other promoter of the Bill together if necessary with such other parliamentary material as is necessary to understand such statements and their effect; and (c) the statements relied on are clear. www.lawteacher.net 5 Asif Tufal PRESUMPTIONS PRESUMPTION CASE EXAMPLE 1. Presumption against changes in the common law 2. Presumption against ousting the jurisdiction of the courts 3. Presumption against interference with vested rights 4. Strict construction of penal laws in favour of the citizen 5. Presumption against retrospective operation 6. Presumption that statutes do no affect the Crown 7. Others www.lawteacher.net 6