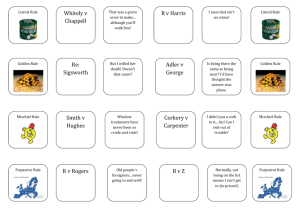

Statutory Interpretation: Rules & Cases

advertisement

Rules of Language and Presumptions: legal terms, words, and cases (Should read).

Aylesbury Mushroom case [1972] - failure to consult - (Must read).

Brock v DPP [1993] - defining words within the statute - (Could read).

Cheeseman v DPP [1990] - a literal approach - (Must Read).

Cutter v Eagle Star [1998] - a literal approach - (Should read)

Fisher v Bell [1960] - a literal approach - (Could read).

Heydon's Case [1584] - Mischief Rule - (Must Read).

Jones v DPP [1962] - Golden Rule (narrow) - (Must Read).

Pepper v Hart [1993] - Referring to Hansard - (Should read).

R v Allen [1872] - Golden Rule (narrow) - (Should Read).

R v Judge of the City of London Court [1892] - the literal rule - (Must read).

R v Registrar General ex parte Smith (1990) - Purposive Approach - (Must

read).

Re Sigsworth [1935] - Golden Rule (wide) - (Should Read).

Smith v Hughes [1960] - Mischief Rule - {Should Read).

Strictland v Hayes Borough Council [1896] - ultra vires - (Should read).

Sweet v Parsley [1970] - mens rea required - (Could read)

Whiteley v Chappell [1868] - literal absurdity - (Must Read).

Rules of language and legal terms: (pages 57 & 58) Jacqueline Martin - The

English Legal System. See also a Law Dictionary.

Ejusdem generis - General words that follow a list are limited to the same

kind - Powell v Kempton Park. In this case, the words 'other place' were held

to mean 'other indoor place', because the list referred to 'house, office,

room or other place' and these terms are all indoors.

Expressio Unis - The express mention of one thing that excludes others Tempest v Kilner.

Noscitur a sociis - A word is known by the company it keeps - IRC v Frere.

Presumptions:

No change to common law - Leach v R

Crown is not bound by any stature unless it expressly says so.

Mens rea required unless statute expressly says otherwise - Sweet v Parsley

(1970)

Legislation is not retrospective.

Aylesbury Mushroom case [1972]. In this case, delegated legislation

required the Minister of Labour to consult 'any organisation... appearing to

him to be representative of substantial numbers of employers engaging in

the activity concerned'. His failure to consult the Mushroom Growers

Association, which represented about 85% of all mushroom growers, meant

that his order establishing a training board was invalid as against mushroom

growers - though it was valid in relation to others affected by the order,

such as farmers, since the Minister had consulted the National Farmers'

Union.

Strictland v Hayes Borough Council [1896] a bylaw that prohibited the

singing or reciting of any obscene song or ballad and the use of obscene

language generally was held to be unreasonable and ultra vires (i.e. it goes

beyond the powers that parliament granted in the enabling Act), because it

was too widely drawn in that it covered acts done in private as well as those

in public.

Brock v DPP [1993]. The Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 used a phrase 'any dog of

the type known as the pit bull terrier' which seems simple but led to

problems. What is meant by type? In Brock v DPP the Queen's Bench

Divisional Court decided that 'type' had a wider meaning than 'breed'. It

could cover dogs who were not pedigree pit bull terriers, but had a

substantial number of the characteristics of such a dog.

Cheeseman v DPP [1990]. Section 28 of the Town & Country Planning Act

1847 provided an offence of 'wilfully and indecently exposing his person in a

street to the annoyance of passengers'.

Police Officers were stationed in a public lavatory in order to apprehend

persons who were committing acts which had given rise to earlier

complaints. The police officers were not resorting to that place of public

resort in the ordinary way but for a special purpose and thus they were not

passengers. Hence the Queen's Bench Divisional - after using the Oxford

English Dictionary to establish what passengers means - allowed the appeal by way of case stated - of Cheeseman against the finding of guilt by the

Leicester Magistrate Court. This is an example of the literal rule to statutory

interpretation.

R v Judge of the City of London Court [1892]. In this case Lord Esher said

(in applying a literal approach):

"If the words of an Act are clear then you must follow them even if they lead

to a manifest absurdity. The court has nothing to do with the question

whether the legislature has committed an absurdity."

The literal rule - developed in the early nineteenth century - has been the

main rule applied ever since then. However, there are variations on this (the

golden rule and mischief rule). More recently, following the development of

European Law, the Courts have been required to take a purposive approach.

Whiteley v Chappell [1868]. In this case the defendant was charged under

a section that made it an offence to impersonate 'any person entitled to

vote'. D had pretended to be a person whose name was on the voter's list,

but had died.

The Court held that he was not guilty since a dead person is not, in the

literal meaning of the words, 'entitled to vote'.

Jones v DPP [1962] - In this case, Lord Reid argues for a narrow application

of the golden rule.

Lord Reid said:

"It is a cardinal principle applicable to all kinds of statutes that you may not

for any reason attach to a statutory provision a meaning which the words of

that statute cannot reasonably bear. If they are capable of more than one

meaning, then you can choose between those meanings, but beyond that

you cannot go."

This means, if there is only one meaning then that must apply (see R v Allen

[1872] for an example of this narrow approach). For a wider application of

the Golden Rule see: Re Sigsworth [1935]).

R v Allen [1872] - Section 57 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861

made it an offence to 'marry' whilst one's original spouse was still alive (and

there had been no divorce). The word 'marry' can mean to become legally

married or to 'go through a ceremony of marriage'. The Court decided that in

the Offences against the Persons Act the word had the second meaning. To

do otherwise would have produced an absurd result.

Re Sigsworth (1935). A son had murdered his mother. The mother had not

made a will, but in accord with rules set out in the Administration of Justice

Act 1925 her next of kin would inherit (who was the son). There was no

ambiguity in the wording of the Act, but the court was not prepared to let a

murderer benefit from his crime. So it was held that the literal rule should

not apply, the golden rule being used to prevent a repugnant situation.

Heydon's Case (1584). This established the Mischief Rule (for an example of

the Mischief Rule see Smith v Hughes) and gives a Judge more discretion

than the Literal or Golden Rule.

In Heydon's Case it was said there were four points a court should consider

(these are paraphrased).

(1) What was the common law before the making of the Act?

(2) What was the mischief and defect for which the common law did not

provide?

(3) What is the remedy Parliament hath resolved?

(4) The true reason of the remedy.

Then the Judges should suppress the mischief and advance the remedy.

Smith v Hughes [1960]. Section 1(1) of the Street Offences Act 1959 said "it

shall be an offence for a common prostitute to loiter or solicit in a street or

public place for the purposes of prostitution."

The court considered appeals by six different women who had been on a

balcony or at the windows of ground floor rooms. In each case, the women

were attracting men by calling to them or tapping on a window. They

argued they were not guilty since they were not in the street.

The court decided they were guilty:

Lord Parker saying:

"For my part I approach the matter by considering what is the mischief

aimed at by this Act. Everybody knows this was an Act to clean up the

streets, to enable people to walk along the streets without being molested

or solicited by common prostitutes. Viewed in this way it can matter little

whether the prostitute is standing in the street or in the doorway or on the

balcony, or at a window, or whether the window is shut or open or half

open."

Sweet v Parsley [1970] - D was charged with being concerned with the use

of premises for the smoking of cannabis. However, she had leased out the

premises and the tenants had smoked the cannabis without her knowledge

(thus, she had no mens rea).

The key issue in the case was whether mens rea was required, given that the

Act did not say whether there was any need for knowledge of events. The

House of Lords held that she was not guilty as the presumption that mens

rea was required had not been rebutted.

Pepper v Hart [1993]. House of Lords accepted that the courts can refer to

Hansard where legislation is (a) ambiguous - (b) statements are made by a

minister or promoter of the Bill - (c) the statements relied on are clear.

R v Registrar General ex parte Smith (1990). Concerned s.51 of the

Adoption Act 1976 which enables a person to obtain details of his birth

certificate when reaching 18 years of age.

There were certain conditions to be undertaken, but the applicant had

undertaken all of these. On a literal view of the law the Registrar-General

had to comply and supply the information. However, in doing so he would

put at risk the life of the applicants natural mother because the applicant

was in Broadmoor Mental Hospital having murdered twice (a psychiatrist

confirmed the danger to the natural mother).

The Court - despite the plain language of the Act - applied a purposive

approach saying: "Parliament could not have intended to promote serious

crime".

[Note: When introducing the Adoption Act 1976 there was no such mischief

to be resolved - thus the mischief rule could not possibly apply].

A purposive approach is now often applicable as a result of European

Law.

Cutter v Eagle Star (1998).

However, as Eagle Star demonstrates, caution must be given when

applying a purposive approach.

The defendant insurance company would be liable to pay damages to Cutter

if the car in which he was injured was on a road when he was injured. The

car was in a car park.

The Court of Appeal decided that a car park was a 'road' for the purposes of

the Road Traffic Act [1988] because it has been Parliament's intention to

provide compensation for those injured in car accidents.

The House of Lords revered this decision. Lord Clyde saying:

"It may be perfectly proper to adopt a stained construction to enable the

object and purpose of legislation to be fulfilled. But it cannot be taken to

applying unnatural meanings to familiar words or to stretch the language

that its former shape is transformed into something which is not only

significantly different but has a name of its own. This must be

particularly so where the language has no evident ambiguity or

uncertainty about it."

Fisher v Bell [1960] A shopkeeper displayed a flick-knife in his window. The

Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959 made it an offence to offer such

a knife for sale. The defendant argued that a display of anything in a show

window is simply an offer to treat and this means that, under contract law,

it is the customer who makes the offer to buy the knife.

Here the court considered that Parliament knew the technical law, at

Common Law, of the term 'offer'.