Statutory interpretation

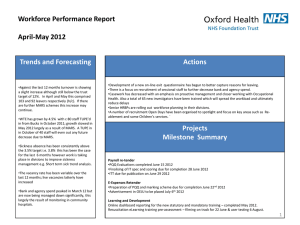

advertisement

Statutory interpretation Aims of the session To identify the issue(s) that surround judicial approaches to statutory interpretation II. To look at the principal ‘rules’ of SI III. Address the critique of these rules IV. To consider some examples of the rules in action I. Role of SI in the legal process No matter how careful the legislative draftsman tries to be – no provision can hope to cater for all circumstances. Lawyers will also argue for alternative ‘interpretations’ of legislation to support client’s case Judges are consequently called on to adjudicate on the meaning and application of legislation. Statutory interpretation arises in the majority of reported cases However… Process of SI is an inherently subjective and human process. Immediately raises a tension about the role of judges in the legal process – passive process of judicial ‘interpretation’ v the more active process of judicial ‘law-making’ Over decades a series of ‘rules of statutory interpretation’ have evolved The ‘rules’ of interpretation 1. 2. The ‘literal’ rule The ‘golden’ rule 3. 4. The ‘mischief’ rule The ‘purposive approach’ Are they really ‘rules’ or just a means of justifying the desired outcome by judges? The Literal Rule 1. When the words of a statute are plain & unambiguous, Parliament must be taken to have meant and intended what it has plainly expressed. 2. What is the justification for the rule – Lord Diplock in Duport Steel v Sirs [1980] 1 WLR 142, at 157 3. Criticisms of the rule The Golden Rule Court must give words their ordinary meaning unless this produces an absurdity – in which case the judge must try to give the words some other contextual meaning…. But is this consistent with the literal rule? The Mischief Rule I. Also known as the rule in Heydon’s case (1584) 3 Co Rep 7a, 7b) – look to the previous common law position and identify the mischief that the legislation sought to correct II. Early example of what is now referred to as the ‘purposive approach’ III. Limitations of the Mischief Rule Purposive Approach Largely supplanted other rules as the most appropriate method of ascertaining Parliament’s intention. R v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, ex p Spath Holme [2001] 2 AC 349, 397 – per Lord Nicholls, this approach bids judges “to identify and give effect to the purpose of the legislation”. Courts now asking ‘what was Parliament really getting at?’ – not just seeking to identify the mischief being remedied…. Why has it become the prevailing approach? Greater openness and acceptance of a proactive judiciary Influence of European Court of Justice, North American courts favour this approach and Human Rights Act 1998 requires judiciary to interpret UK legislation so as to ensure conformity What are the (potential) problems with the rule? Pepper v Hart [1992] 3 WLR 1032 Permits recourse to extraneous materials, i.e. Hansard provided 3 conditions satisfied. Problems in applying the conditions - see R v Secretary of State, ex p Spath Holme [2001] 1 All ER 195 Rule in Pepper v Hart also applies to other documents like Reports of Law Reform Commissions, Dept Scrutiny Committees etc. Role of ‘Presumptions’ in Statutory Interpretation 1. In addition to the rules of SI – judges may also rely on a range of ‘presumptions’ to assist in the process of SI 2. Presumptions are the “background of legal principles against which the Act must be viewed, and in the light of which Parliament is assumed to have legislated.” 3. Presumptions are ‘implicit’ to legislation Some Examples… 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Legislation adopted by UK Parl will only apply within the UK… Presumption against interference with personal liberty A person cannot profit from his own wrongdoing Presumption against the taking of property without compensation Legislation can authorise an activity expressly or “by reasonable implication” Take a break Aims of this part of the session I. II. To illustrate how different approaches to interpretation can lead to different results in practice Three cases: Re Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission [2001] NI 271 & [2002] NI 236; Robinson v Secretary of State for the Northern Ireland [2002] NI 207 & 390; and Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] 3 All ER 411 NIHRC – the issues The origins and purposes of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission (NIHRC) Wished to intervene in a Coroners Inquest Coroner considered that the NIHRC didn’t have an express statutory power to intervene NIHRC sought judicial review of that decision, arguing that the power was either express or implicit Commission’s Statutory Role Northern Ireland Act 1998, s 69: “keep under review the adequacy and effectiveness … of law and practice relating to the protection of human rights” (69(1)) make recommendations to the Secretary of State (69(2)) assist individuals involved in proceedings (69(5)(a)) “promote understanding and awareness of the importance of human rights” (69(6)) The contrasting approaches of Carswell LCJ and Kerr J Carswell LCJ said: “The Human Rights Commission has not been given any overall function such as advancing the observance of human rights. On the contrary, its functions set out in section 69 are specific and fairly precise and do not seem to me capable by reasonable implication of extending to making submissions to the coroner at an inquest” In contrast, Kerr LJ ruled… that it “unmistakable” that the NIHRC had been given an overall role. He thus found that the power to intervene was expressly provided for by section 69(6) Failing that, he considered that the power could be read as “incidental to or consequential upon its general duty to promote the observance of human rights” Majority of NICA agreed with Carswell LCJ; majority of the HL agreed with Kerr J Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza – the issues I. II. III. IV. Homosexual relationship, which was stable and monogamous Mr Wallwyn-James was a protected tenant; Mr Godin-Mendoza was his partner Mr Wallwyn-James died and the landlord sought possession of the flat Held that Mr Godin-Mendoza did not succeed to the tenancy as a surviving “spouse”, but was entitled to an assured tenancy by succession as a member of the original tenant’s “family” Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza – the legislation Para 2(1) of Schedule 1 of the Rent Act 1977: “The surviving spouse … shall after the death be the statutory tenant” Para 2(2): “ … a person living with the original tenant as his or her wife or husband shall be treated as the spouse of the original tenant” (unmarried heterosexual couples) Section 3 of the HRA: “So far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation … must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights” (Articles 8 & 14 ECHR) Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza – the decision It was possible to read the legislation in a way that “spouse” included the survivor of a same-sex partnership But see Lord Millett’s dissenting opinion: “These are questions of social policy which should be left to Parliament … it is in my view not open to the courts to (adopt) an interpretation of the existing legislation which it not only does not bear but which is manifestly inconsistent with it” And see now the Civil Partnerships Act 2004 Conclusions Important to remember that the rules of SI are not absolute Judicial personalities and perspectives play a major role in how rules of SI are applied Little doubt that the purposive approach to SI is on the rise …