Englishness, civil society and linguistic identity in Britain

advertisement

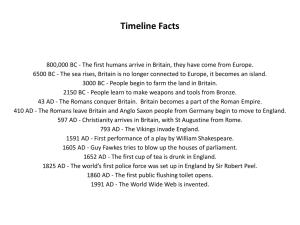

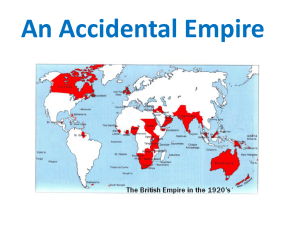

Englishness, civil society and linguistic identity in Britain In Paxman’s words: “The greatest legacy the English have bequeated the rest of humanity is their language.” Indeed, English has been the most expansive language during the past 500 years and its rise has triggered one of the most exciting debates on language policy of our days. The questions are basically: Why English? How did English develop externally and internally to become the leading world language? How did English jump from being one of the few powerful international, colonial languages, to the status of the hegemonic world language? The British Empire and the Rise of English The British Empire developed in three distinct periods with different results as regards the spread of the English language. During a 1st period throughout the Middle Ages, English spread over the British Isles, setting the stage for becoming the language of the British Empire. The 2nd period began at the end of the 16th century with settlements in North America and, later on, in Australia and New Zealand. The 3rd period came towards the end of the 18th century with the building of a vast colonial empire, mainly in Africa and Asia. The first period (Middle Ages) allowed English to emerge from a subordinate position in a Norman French vs. English diglossia to become the national language of one of the most powerful European empires. It represented a combination of nation building and internal colonialism in the periphery (Wales, Scotland and Ireland) as Britain never achieved total linguistic unification in its homeland. The historical influence of language in the British Isles can best be seen in place names and their derivations. Examples include: ac (as in Acton, Oakwood) which is Anglo-Saxon for “oak”; by (as in Whitby) is Old Norse for “farm” or “village”; pwll (as in Liverpool) is Welsh for “anchorage”. The second period (end of 16th century – 18th century) laid the ground for English world rule through the conquest, massive settlement, and future industrial development of North America, Australia and New Zealand. The first New World settlement was established in Jamestown in 1607. During the 17th century, British rule was established in the West Indian islands of Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago. Canada was won from the French in 1763. British rule in India was established in 1750, although the East India Company had existed since 1600. Australia and New Zealand were discovered during Captain Cook's voyages between 1768 and 1779. The third period (end 18th century) saw the British rule as being finally established in West Africa (Nigeria), East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania) and Southern Africa (Zimbabwe). The complex processes of exploration, colonization and overseas trade that characterized Britain’s external relations for several centuries led English to be imposed as the official language of the new colonies but also brought significant changes in English itself. Indeed, words from the local languages trickled into the English of the colonisers. This occurred most frequently where an equivalent word did not exist in English: barbecue and cannibal are words which have been borrowed from the Caribbean; bungalow, pyjamas, shampoo, pundit have come into the language from India; kangaroo and boomerang are native Australian Aborigine words. New words were also absorbed via the languages of other trading and imperial nations such as Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands. At the same time new varieties of English emerged, each with their own nuances of vocabulary and grammar and their own distinct pronunciations. The development of English from a colonial language to a global language, to a lingua franca regularly used and understood by many nations for whom English is not their first language has been framed by the linguist Kachru (1982, 1986), both in its external spread and in its internal variation. His model of three concentric circles is widely quoted The Inner Circle includes the six countries where English is the first language and has become the majority language through massive migration to the overseas colonies: Britain Ireland the USA anglophone Canada Australia New Zealand some of the Caribbean territories The Outer Circle includes countries where English is not the native tongue, but is important for historical reasons and plays a part in the nation’s institutions, either as an official language or otherwise. India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Tanzania, Pakistan, Singapore and Nigeria are considered typical countries of the Outer Circle where new varieties of English arose over time through contact with native languages. The Expanding Circle includes countries where English plays no historical or governmental role but is widely used as a foreign language or lingua franca; these countries were not colonized by any country of the Inner Circle, and English has no official status. This circle includes countries like China, Japan, Korea, Russia and most if not all European and Latin American countries. The Expanding Circle is growing fast and has already outnumbered the speakers in the two other circles. The linguistic development of English We said that the English language spread throughout the world thanks to the spread of the British Empire but it is necessary to point out that the English language we nowadays speak is the result of a series of linguistic internal changes that led to its present structure. Early Modern English (1500-1800) Since the 16th century, because of the contact that the British had with many peoples from around the world, many new words and phrases have entered the language either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, new words and phrases were created at an increasing rate and many of them that are now commonly used were coined or first recorded by Shakespeare: indeed, some 2,000 words and countless idioms are his. Newcomers to Shakespeare are often shocked at the number of cliches contained in his plays, until they realize that he coined them and they became cliches afterwards. "At one fell swoop," "vanish into thin air" and "flesh and blood" are all Shakespeare's. Words he bequeathed to the language include "critical", "majestic", "dwindle" and "pedant" Two other major factors influenced the English language and served to separate Middle English and Modern English. The first was the Great Vowel Shift. This was a sudden and distinct change in pronunciation that began around 1400 according to which vowels were pronounced shorter and shorter, with their sounds being made further to the front of the mouth and the letter "e" at the end of words becoming silent. Chaucer's Lyf (pronounced "leef") became the modern life. In Middle English name was pronounced "nam-a," five was pronounced "feef," and down was pronounced "doon." The shift is still not over, vowel sounds are still shortening although the change has become considerably more gradual. The last major factor in the development of Modern English was the advent of the printing press. William Caxton brought the printing press to England in 1476. Books became cheaper and as a result, literacy became more common. Publishing for the masses became a profitable enterprise, and works in English, as opposed to Latin, became more common. Furthermore, the printing press brought standardization to English. Indeed, the dialect of London, where most publishing houses were located, became the standard. As it began to be used more widely, especially in formal contexts and amongst the upper classes, the other regional varieties came to be stigmatized, as lacking social prestige and indicating a lack of education. As a result of this also spelling and grammar became fixed, and the first English dictionary was published in 1604. Late Modern English (1800-Present) The main distinction between Early and Late Modern English is vocabulary. Pronunciation, grammar, and spelling are largely the same, but Late Modern English has many more words which are the result of two historical factors The first is the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century and the rise of the technological society which created a need for neologisms to describe the new creations and discoveries. For this, English relied heavily on Latin and Greek. Words like oxygen, protein, nuclear did not exist in the classical languages, but they were created from Latin and Greek roots. However, these neologisms were not exclusively created from classical roots as English roots were also used for such terms as horsepower, airplane, and typewriter. Furthermore, new technical words were added to the vocabulary as inventors designed various products and machinery; these words were named after the inventor or given the name of their choice: trains, engine, combustion, electricity, telephone, telegraph, camera etc. In addition to this, the rise of the British Empire, its ruling – at its height – one quarter of the earth’s surface between the 18th and the 20th centuries and the growth of global trade served not only to introduce English to the world, but to introduce foreign words into English In this sense, it is also interesting to note that the British Empire was a maritime empire, and the influence of nautical terms on the English language has been great; phrases like three sheets to the wind have their origins onboard ships. Finally, the military influence on the language during the second half of the 20th century was significant. Before the Great War, military service for English-speaking persons was rare; both Britain and the United States maintained small, volunteer militaries. Military slang existed, but, with the exception of nautical terms, rarely influenced standard English. During the mid-20th century, however, a large number of British and American men served in the military. And consequently military slang entered the language like never before. Blockbuster, camouflage, radar, roadblock, spearhead and landing strip are all military terms that made their way into standard English. A brief chronology of English Middle English c1400 The Great Vowel Shift begins. 1476 William Caxton establishes the first English printing press. 1564 Shakespeare is born. 1604 Table Alphabeticall, the first English dictionary, is published. 1607 1702 The first permanent English settlement in the New World Early (Jamestown) is established. Modern English The first daily English-language newspaper, The Daily Courant, is published in London. 1755 Samuel Johnson publishes his English dictionary. 1782 Britain abandons its colonies in what is later to become the USA. 1828 Webster publishes his American English dictionary. 1922 The British Broadcasting Corporation is founded. 1928 The Oxford English Dictionary is published. Late Modern English The British attitude towards English We said that English is now a global language, a lingua franca, but to the British language is much more than a means of communication – it is a cultural heritage, something to be held up for display and treasured and admired for its own worth. The Complete Oxford Dictionary runs to 23 volumes and contains over 500.000 words; new words appear everyday, highlighting the growth of English as something the British exult in, as they consider verbal evolution as a mark of success. The British love of words From a sociolinguistic point of view, one of the distinguishing features of the British is their love of words, seen as their preferred medium – as well as, consequently, as their primary means of signalling and recognising social status. Jeremy Paxman calls the English “a people obsessed by words”, and cites the phenomenal output of their publishing industry (100.000 new books a year). Reading books ranks as even more popular than DIY and gardening in national surveys of leisure activity and it is worth noting that every one of the non-verbal hobbies and pastimes that occupy their leisure time – such as fishing, stamp collecting, pets, walking, sports etc. – has at least one if not many more specialist magazines devoted to it. Over 80% of the English regularly read a daily newspaper. In England, daily papers are also known as “broadsheets” because of their large format, something that leads them to be the favourite reading of the English as they are large enough for every reader to hide behind. In this sense, the English broadsheet is an example of what psychologists call a “barrier signal”. Indeed, not only can one conceal oneself completely behind its outsize, outstretched pages – effectively prohibiting any form of interaction with other humans, and successfully maintaining the comforting illusion that they do not exist – but one is enclosed, cocooned in a solid wall of words. This is typically British. Some sociolinguists assume that the English love of words, and their passion for word games and verbal puzzles is most perfectly demonstrated not by the wit of the broadsheet columnists, brilliant though they are, but by the journalists and subeditors who write the headlines in the tabloids. If you take a random selection of English tabloids and flip through them, you will soon notice that almost every other headline involves some kind of play on words: a pun a double meaning a deliberate jokey misspelling a clever neologism a cunning rhyme an amusing alitteration, and so on. The English attitude to play with words is also to be seen in place names. Let’s consider the Underground stations in London: their names nearly always sound sylvan and beckoning: Stamford Brook Turnham Green Maida Vale Drayton Park. We could say that there isn’t a city up there, it’s a Jane Austen novel. It’s easy to imagine that you are shuttling about under a semimythic city from some golden preindustrial age. Swiss Cottage ceases to be a busy road junction and becomes instead a gingerbread dwelling in the midts of the great oak forest known as St. John’s Wood. Chalk Farm (an area in north London) is an open space of fields where cheerful peasants in brown smocks cut and gather crops of chalk. Blackfriars is full of cowled and chanting monks Oxford Circus has its bigtop Barking is a dangerous place overrun with packs of wild dogs Holland Park is full of windmills. From a general point of view, there is almost no area of British life that isn’t touched with a kind of genius for names. Select any area of nomenclature at all prisons: Wormwood Scrubs, Strangeways pubs: The Cat and Fiddle, The Lamb and Flag soccer teams: Queen of the South and you are in for a spell of enchantment. Nowhere are the British more gifted than with place names. Of the 30.000 named places in Britain a good half are notable or arresting in some way. There are villages that seem to hide some ancient and possibly dark secret : Husbands Bosworth, Whiteladies Aston sound like characters from a bad 19th entury novel: Compton Valence sound like fertilizers: Hastigrow sound like breath fresheners: Minto sound like skin complaints: Whiterashes. All this is typically British. Linguistic political correctness There is another important aspect to point out with regard to how English is nowadays seen within the British society: indeed, political correctness now governs the worthiness of many English words. Hundreds of euphemisms have sprung up to cope with problematic issues and vocabulary the handicapped are now “mobilitychallenged” the blind “seeing impaired” the not so bright “knowledge-base nonpossessors” people don’t have pets, they have “companion animals” people are neither short nor fat, but “vertically challenged” or “persons of size”. All this is strictly related to the issue of politeness and can be clearly observed in greetings and, in particular, in the problems involved in first-time introductions. Nowadays, the most common solution in this regard is “Pleased to meet you” (or “Nice to meet you” or something similar). But in some social circles, mainly uppermiddle classes and above, the problem with this common response is that it is just that, ‘common’, meaning a lower-class thing to say. They will then assume that “Pleased to meet you” is ‘incorrect’, something that is confirmed also by some etiquette books, according to which one should not say “Pleased to meet you” as it is an obvious lie: one cannot possibly be sure at that point whether one is pleased to meet the person or not Even though the British courtesy is often just mere pretence, foreign visitors are usually impressed by it, which is defined by sociolinguists Brown and Levinson as “negative politeness”, meaning that it is concerned with other people’s need not to be intruded or imposed upon (as opposed to “positive politeness” which is concerned with their need for inclusion and social approval), as if the English judged others by themselves and assumed that everyone else shared their obsessive need for privacy. Politeness by definition involves a degree of artifice and hypocrisy, but English verbal courtesy seems to be almost entirely a matter of form, of obedience to a set of rules rather than expression of genuine concern. The English are not naturally socially skilled: they need all these rules to protect them from themselves. Key phrases therefore include “Sorry” “Please” “Thank you/Cheers/Ta/Thanks” “I’m afraid that…” “I’m sorry but…” “Would you mind…?” “Could you possibly…?” “Excuse me, sorry, but you couldn’t possibly pass the marmalade, could you?” “Excuse me, I’m terribly sorry but you seem to be standing on my foot”. Language and social class Such linguistic diplomacy also concerns the English acute class-consciousness, as the language is often used by the English as a disguise to their being intensely conscious of status differences their endless “pleases” disguise orders and instructions as requests their constant “thank-yous” maintains an illusion of friendly equality, which in reality doesn’t exist. This is also related to their national obsession to be able to “place” one another on the social scale: for them, it is vital to avoid making a mistake about someone’s social position. Accent Accent can instantly place an individual. A regional drawl is no longer considered the fatal flaw it once was, but what used to be called an “Oxford” accent or BBC pronunciation can still give advantage to someone with it. In particular, the first class indicator concerns which type of letter the English favour in their pronunciation, or rather which type they fail to pronounce. In particular, the lower classes fail to pronounce consonants whereas the upper classes drop their vowels. For example, if you ask them the time, the lower classes may tell you it is “alf past ten” but the upper classes will say “hpstn”. A handkerchief in working-class speech us “ankercheef” but in upper-class pronunciation becomes “hnkrchf”. Upper-class vowel-dropping may be frightfully smart, but it still sounds like a mobile-phone message, and unless you are used to this clipped, abbreviated way of talking, it is no more intelligible than lower-class consonant-dropping. The upper classes do at least pronounce their consonants correctly whereas the lower classes often pronounce “th” as “f” (“teeth” becomes “teef”, “thing” becomes “fing”) or sometimes as “v” (“that” becomes “vat”). Final ‘g’s can become ‘k’s, as in “somefink” (something) or “nuffink” (nothing). Pronunciation of vowels is also a helpful class indicator. Lower-class ‘a’s are often pronounced as long ‘i’s, as in Dive for Dave, Tricey for Tracey. Working class ‘i’s may be pronounced ‘oi’. But the upper classes don’t say ‘I’ at all if they can help it: one prefers to refer to oneself as ‘one’. In fact, they are not too keen on pronouns in general, omitting them, along with articles and conjunctions, wherever possible (as Fox states: “as though they were sending a frightfully expensive telegram”). British English and American English With regard to the spread of English in the American territory, the British colonization of North America resulted in the creation of a distinct American variety of English. Some English pronunciations and usages "froze" when they reached the American shore: this implies that, in some ways, American English is closer to the English of Shakespeare than modern Standard British English is Some expressions that the British call "Americanisms" are in fact original British expressions that were preserved in the colonies while lost for a time in Britain: trash for “rubbish” loan as a verb instead of “lend” fall for “autumn”. The American dialect also served as the route of introduction for many native American words into the English language. Most often, these were place names like Mississippi and Iowa but names for other things besides places were also common. Raccoon, tomato, canoe, barbecue, savanna, and hickory have native American roots, although in many cases the original Indian words were mangled almost beyond recognition. British attitude towards American English The English attitude toward Americanisms is often hostile and this xenophobia occasionally touches peaks of smugness. Recently, during a debate in the House of Lords, one of the members said: “If there is a more hideous language on the face of the earth than the American form of English, I should like to know what it is”. The British consider American Speech to be remarkably straightforward. Americans tell it as it is. Linguistic subtlety, innuendo, and irony that the British find delightful puzzle the Americans, who take most statements at face value, weigh them for accuracy, and reject anything they don’t understand. They call spades spades and have troubles with complex metaphors. British say that Americans particularly love new words and adopt them with alacrity. They also use them to death. They not only pick up useful words and phrases from every corner of the world, they readily move on to new words when the old words go out of fashion – a constant reinvention that results in enlarging the dictionary, a feature that is crucial also within British English, which is in a constant state of flux.