Popular Culture and Expressions of Australian

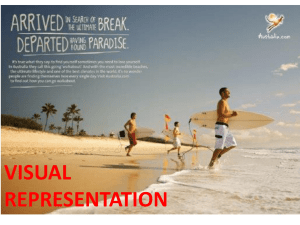

advertisement

Popular Culture and Expressions of Australian National Identity Dr Sarah Baker Lecturer, Cultural Sociology School of Humanities, Griffith University Friday 1 October, 10am-12pm Volda University College Australasian Study Tour Defining Culture • “the whole way of life of a people, their customs and rituals, their pastimes and pleasures, including not only the arts but also practices such as sport and going to the beach” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: viii) • “Culture in this sense is the result of the multifarious processes of making meanings for a society.” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: x) • “Culture is a producer and re-producer of value systems and power relations, performing crucial ideological functions within Australia.” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: x) Reading “Texts” (Semiotics) • “The study of the social production of meaning from sign systems” (O’Sullivan et al 1994: 281) • Sign – “anything that has an accepted meaning for a person or group of people”. – Signifier – “the carrier of meaning” – Signified – “the mental concept to which the sign refers” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: xi) Union Jack: Heritage? Tradition? Dependence? Loyalty to the British Empire? Commonwealth star: Belonging to the West? Part of something bigger? Blue: Girt by sea? Colours of the empire? Southern Cross: Visible in the Southern hemisphere – morale virtues of Dante? Myth • Myth - “a systematic organisation of signifiers around a set of connotations and meanings” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: xi) • “has an important role within ideas of nation, where it is an essential part of cultural meaning and maintenance. Foundations of national ideas and values are established through myth and highlight what is considered natural and accepted or alien and excluded within a culture. These continuous narratives are embedded with various rituals and symbols leading to a collective discourse.” (Price 2010: 453) The ‘Myth’ of Australia Example: GANGgajang – Sounds of Then (This is Australia) Activity: List all of the symbols in the GANGgajang music video that help construct our understanding of ‘Australia’. The Beach and Australian Identity • “so much of Australia seems to be about pleasure – made for it. Especially the South East coastline along which the majority of Australians choose to live. The beach has become an integral part of our life and our identity” – Robert Hughes, art critic. (cited in Bonner, McKay and McKee 2001: 270) • “The voice-over tells us about Australian national identity as Webster lays down her beach towel and prepares to … ‘dream, as we all do, of wide blue skies, the sand and the sea’.” (p. 269) • “Surf lifesavers ran into the arena at the end … They were pulling Kylie Minogue on a giant thong, and she stood up and surfed on it as she entered the arena.” (p. 273) (Bonner, McKay and McKee 2001) • “The interplay of culture and nature is an important myth-generating mechanism to address the plight of contemporary Australian existence. Fiske and colleagues (1987) connect the rising importance of the beach in Australian culture to the rise of urbanization, which made redundant older myths of the bush, the bush ranger (symbolized by Ned Kelly) and an isolated hideaway. Instead, suburban-dwelling Australians brought nature into culture and vice versa, by means of the beach”. (Hartley and Green 2006: 348) From the Bush to the Beach The Beach and the City • “So, as the bushman became less relevant to modern Australia, the ideology which once mythologised him, valuing his harmony with the natural environment and his tough physicality, now supports the beach. Consequently the central image of the Australian beach is not that of the tropical hideaway. That does exist, but is reserved for holidays, preferably outside Australia. The beach that contributes to everyday existence must be metropolitan, therefore urban.” (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: xi) • “the values traditionally associated with the Aussie Digger [were] reinvested in the lifesaver. Through the lifesaver, humanitariansim, mateship, ablebodiedness, racial purity, heroic sacrifice, and public service/duty continued from the rhetoric of war to public safety”. The Lifesaver (Evers 2008: 418) • “…he fights the elements to preserve the lives of citizens at innocent play... Like the Anzac he represents discipline and sacrifice … The representation embodies the best of the old images and reworks them into a new modern form”. (Saunders, cited in Price 2010: 454) • “Central to the format are the lifeguards’ characters as mythic heroes … This portrayal is consistent with the national type identified with the ‘sun-bronzed physique, the masculinity, the cult of mateship, the military associations, the hedonism and wholesomeness of the beach’ … The lifeguards are referred to … as … ‘cast from a vintage Australian mould’ … as a reflection of their mythic qualities ...” (Price 2010: 455) Streets Beach, South Bank • Activity: site observation of Streets Beach. • Questions: How is the ‘myth’ played out at this beach? In what ways does Streets Beach confirm and/or challenge what you have learned in the lecture so far? The Surfer • “…while lifesavers give up their time to ‘patrol’ the beach, surfers are seen to be indulging themselves on the beach all day whilst living on the dole. If the lifesavers are the heroes of this myth, then the surfers are its anti-heroes”. (Fiske, Hodge and Turner 1987: 65) • “Cronulla … can be a dangerous place to go surfing. Shark Island is the premier wave of the area ... The waves at this surf break rise, warp, peel, and mutate over a shallow slab of rock. The men who ride the island are respected by other surfers and are considered brave and tough. … These men know how to negotiate the dangers of Shark Island. They paddle out to the waves through currents hidden below the surface of the water, which help them avoid the harm of the exploding swells. The men can tell at a glance what waves will peel evenly and allow a safe ride”. (Evers 2008: 418) Surfer as underdog • “The ‘battler’ figures within Australian cultural history as the embodiment of national values of hard-work, egalitarianism and perseverance. … the battler is closely related to the pioneer myth … In essence, the battler is an underdog figure, someone who struggles to succeed against-the-odds”. (Butler 2009: 392) The white, bronzed Aussie • “the battler is the key actor in the drama of white Australian history; the key exponent of the ‘Australian’ values of egalitarianism and mateship. The whiteness of the battler is amplified by the historical resonance of the term – it’s very mustiness harks back to an earlier time when inequalities of income were not strongly associated with ethnicity, and when nonwhites did not struggle economically (because they were politically invisible).” (Scalmer, cited in Butler 2009: 399) Cronulla Riots • “On Sunday December 4, two teenage volunteer lifesavers were attacked by two males, apparently Lebanese. The attack provoked a very hostile reaction in and around the beach. Lifesavers get respect from the Australian community, particularly in beachside areas. People know that lifesavers do literally save lives. The weekend volunteers are not paid for what they do. For someone to attack lifesavers was to commit a very provocative act which was likely to cause an angry reaction”. (Barclay and West 2006: 77) This is Australia? • “In contrast [to confrontations based on competition for land or labour], as the use of the Australian flag, the national anthem, and rioters’ appeals to other national icons and the Australian way of life indicate, the contemporary challenge involves ownership and access to membership in the nation and its culture.” (Inglis cited in Hartley and Green 2006: 352) References • • • • • • • • Barclay, Ryan and West, Peter 2006, ‘Racism or patriotism? An eyewitness account of the Cronulla demonstration of 11 December 2005’, People and Place, 14(1): 75-85. Bonner, Frances, McKay, Susan and McKee, Alan 2001, ‘On the beach’, Continuum, 15(3): 269-274. Butler, Kelly Jean 2009, ‘‘Their culture has survived’: Witnessing to (dis)possession in Bra Boys (2007)’, Journal of Australian Studies, 33(4): 391-404. Evers, Clifton 2008, ‘The Cronulla race riots: Safety maps on an Australian beach’, South Atlantic Quarterly, 107(2): 411-429. Fiske, John, Hodge, Bob and Turner, Graeme 1987, Myths of Oz: Reading Australian Popular Culture, Allen & Unwin, Sydney. Hartley, John and Green, Joshua 2006, ‘The public sphere on the beach’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(3): 342-362. O’Sullivan, Tim, Hartley, John, Saunders, Danny, Montgomery, Martin and Fiske, John 1994, Key Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies, 2nd edition, Routledge, London. Price, Emma 2010, ‘Reinforcing the myth: Constructing Australian identity in ‘reality TV’’, Continuum, 24(3): 451-459.

![PERSONAL COMPUTERS CMPE 3 [Class # 20524]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005319327_1-bc28b45eaf5c481cf19c91f412881c12-300x300.png)