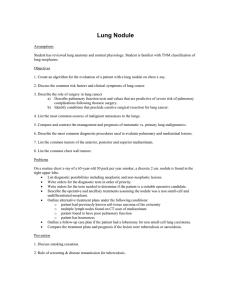

30 Lower Respiratory Problems Eugene E. Mondor http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lewis/medsurg/ CONCEPTUAL FOCUS Cellular Regulation Clotting Functional Ability Gas Exchange Infection LEARNING OUTCOMES 1.Compare and contrast the clinical manifestations and nursing and interprofessional management of patients with acute bronchitis and pertussis. 2.Distinguish among the types of pneumonia and their etiology. 3.Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, and interprofessional and nursing management of patients with pneumonia. 4.Explain the pathophysiology, classification, clinical manifestations, complications, diagnostic abnormalities, and interprofessional and nursing management of patients with tuberculosis. 5.Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and interprofessional management of a patient with a lung abscess. 6.Identify the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and interprofessional management of a patient with a pleural effusion. 7.Compare and contrast the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and interprofessional management of fractured ribs, flail chest, and pneumothorax. 8.Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and interprofessional management of pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale. 9.Identify the causative factors, clinical manifestations, and nursing and interprofessional management of patients with environmental lung diseases. 10.State lung disorders in which lung transplantation may be a treatment option, explaining the nursing and interprofessional management of the transplant patient. 11.Describe the etiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and interprofessional and nursing management of the patient with lung cancer. KEY TERMS acute bronchitis community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) cor pulmonale empyema flail chest hemothorax hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) lung abscess pertussis pleural effusion pleurisy (pleuritis) pneumoconiosis pneumonia pneumothorax pulmonary edema pulmonary embolism (PE) pulmonary hypertension tension pneumothorax tuberculosis (TB) A variety of problems affect the lower respiratory system. This chapter discusses lower respiratory tract diseases that influence gas exchange. We will focus on infectious, restrictive, traumatic, vascular, environmental, and oncologic problems that have the potential to impair gas exchange. Left untreated, many of these conditions will have profound consequences for the patient, as adequate oxygenation and ventilation are both essential for life. 596 CHAPTER 30 Lower Respiratory Problems 597 LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS PERTUSSIS Lower respiratory tract infection is a common and serious problem. It is the reason for thousands of clinic and emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions each year. In the United States, pneumonia and influenza cause around 50,000 deaths each year.1 Pertussis is a highly contagious respiratory tract infection. It is caused by the gram-negative bacillus Bordetella pertussis. The bacteria attach to the cilia of the respiratory tract and release toxins that damage the cilia, causing inflammation and swelling. Cases of pertussis have been steadily increasing in the United States since the 1980s.2 The largest increase is in teens and adults. We think that immunity from childhood tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine (Tdap) vaccination may decrease over time, allowing a milder (but still contagious) infection to occur. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends that all adolescents (11 years and older) and adults who have not received a dose of Tdap receive a onetime vaccination as soon as possible.3 Manifestations of pertussis occur in stages. The 1st stage, lasting 1 to 2 weeks, manifests as a mild upper respiratory tract infection (URI) with a low-grade or no fever, runny nose, watery eyes, malaise, and mild, nonproductive cough. The 2nd stage, from the 2nd to 10th weeks of infection, is characterized by paroxysms of cough. The last stage lasts 2 to 3 weeks. The cough is less severe. The patient may still be weak. The hallmark characteristic of pertussis is uncontrollable, violent coughing. Inspiration after each cough produces the typical “whooping” sound as the patient tries to breathe in air against an obstructed glottis. The “whoop” is often not present in teens and adults (especially those who are vaccinated). Coughing is more frequent at night. Vomiting may occur with coughing. Unlike acute bronchitis, the cough with pertussis may last from 6 to 10 weeks. In the community, diagnosis is mainly by history and assessment. In the acute care setting, the CDC recommends nasopharyngeal cultures, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of nasopharyngeal secretions, or serology testing.4 The treatment is macrolide (erythromycin, azithromycin) antibiotics to minimize symptoms and prevent disease spread (see Table 15.8). For the patient who cannot take macrolides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is used. The patient is infectious from the beginning of the 1st stage through the 3rd week after onset of symptoms or until 5 days after starting antibiotic therapy. Place hospitalized patients on droplet precautions. Patients should not use cough suppressants and antihistamines as they are ineffective and may cause coughing. Corticosteroids and bronchodilators are also not helpful. The CDC recommends antibiotic therapy for those who had close contact with the patient. ACUTE BRONCHITIS Acute bronchitis is a self-limiting inflammation of the bronchi in the lower respiratory tract. It is the reason for 2.7 million outpatient clinic visits and 4 million ED visits per year. Viruses cause most acute bronchial infections. Air pollution, dust, inhalation of chemicals, smoking, chronic sinusitis, and asthma are other triggers. Cough is the most common symptom. It may last for up to 3 weeks and is the main reason for seeking medical care. Coughing is more frequent at night. When present, sputum is often clear, although some patients have purulent sputum. Other symptoms may include headache, fever, malaise, hoarseness, myalgias, dyspnea, and chest pain. Diagnosis is based on the assessment. Assessment may reveal normal breath sounds or crackles or wheezes, usually on expiration and with exertion. Consolidation (when fluid accumulates in the lungs), suggestive of pneumonia, is absent with bronchitis. Chest x-rays are normal and not needed unless we suspect pneumonia or some other lung problem. The goal of treatment is to relieve symptoms and prevent pneumonia. Treatment is supportive. It includes cough suppressants (e.g., dextromethorphan), encouraging oral fluid intake, and using a humidifier. Throat lozenges, hot tea, and honey may help relieve cough. β2-agonist (bronchodilator) inhalers are useful for patients with wheezes or underlying lung problems. We do not prescribe antibiotics for viral infections because they are not effective against viruses and giving them promotes antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics may be given to patients with underlying chronic conditions who are at risk for or have a prolonged infection with systemic symptoms. Encourage patients to not smoke, avoid secondhand smoke, and wash their hands often (Box 30.1). If acute bronchitis is due to influenza, we may start treatment with antiviral drugs. If patients with acute bronchitis develop a fever, have trouble breathing, or have symptoms last longer than 4 weeks, they should see their HCP. BOX 30.1 HEALTH PROMOTING POPULATION Preventing Respiratory Diseases • Wash hands often to prevent and avoid spreading infections. • Get a Tdap, pneumococcal, COVID, and flu vaccines as directed by the HCP. • Avoid smoking and exposure to environmental smoke. • Wear proper personal protective equipment (PPE) when working in an occupation with prolonged exposure to dust, fumes, or gases. • Avoid exposure to allergens, indoor pollutants, and ambient air pollutants. PNEUMONIA Pneumonia is an acute infection of the lung parenchyma. Despite progress in antibiotic therapy to treat pneumonia, pneumonia still has significant morbidity and mortality. Pneumonia and lower respiratory tract infections were the 4th leading cause of death worldwide in 2019.5 Etiology Normally, various defense mechanisms protect the airway distal to the larynx from infection. Mechanisms that create a 598 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation mechanical barrier to microorganisms entering the tracheobronchial tree include air filtration, epiglottis closure over the trachea, cough reflex, mucociliary escalator mechanism, and reflex bronchoconstriction. Immune defense mechanisms include secretion of immunoglobulins A and G and alveolar macrophages. Pneumonia is more likely to occur when defense mechanisms become incompetent or are overwhelmed by the virulence or quantity of infectious agents. A weakened cough or epiglottal reflex may allow aspiration of oropharyngeal contents into the lungs. Tracheal intubation bypasses normal filtration processes and interferes with the cough reflex and mucociliary escalator mechanism. Air pollution, smoking, viral URIs, and normal changes that occur with aging can impair the mucociliary mechanism. Chronic diseases can suppress the immune system’s ability to inhibit bacterial growth. Risk factors for pneumonia are listed in Table 30.1. Pathogens that cause pneumonia reach the lung in 3 ways: 1.Aspiration of normal flora from the nasopharynx or oropharynx. Many organisms that cause pneumonia are normal inhabitants of the mouth and pharynx in healthy adults. 2.Inhalation of microbes present in the air. Examples include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal pneumonias. 3.Hematogenous spread from a primary infection elsewhere in the body. One example is Staphylococcus aureus from infective endocarditis. Classifications of Pneumonia There is no universally accepted classification system for pneumonia. Some classify pneumonia by the causative pathogens (e.g., bacterial, viral, fungal), disease characteristics, or appearance on chest x-ray. The most widely recognized and effective way to classify pneumonia is as either community-acquired or hospital-acquired pneumonia. This classification helps the HCP TABLE 30.1 Risk Factors for Pneumonia • Abdominal or chest surgery • Age >65 years • Air pollution • Altered level of consciousness (e.g., head injury, seizures, anesthesia, drug overdose, stroke) • Bed rest and prolonged immobility • Chronic diseases: chronic lung and liver disease, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease • Debilitating illness • Enteral feedings via naso- or orogastric or intestinal tubes • Exposure to bats, birds, rabbits, and farm animal feces • Immunosuppressive conditions and/or therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, cancer chemotherapy, HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplant) • Inhalation or aspiration of noxious substances • IV drug use • Malnutrition • Resident of a long-term care facility • Smoking • Tracheal intubation (endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy) • URI identify the most likely cause (Table 30.2) and the choice of antimicrobial therapy. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an acute lung infection that occurs in patients who have not been hospitalized or lived in a long-term care facility within 14 days of symptom onset. The decision to treat the patient at home or admit to a hospital is based on several factors. These include the patient’s age, vital signs, mental status, presence of co-morbid conditions, and condition. We can use various tools (Table 30.3) to support clinical judgment. Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), or nosocomial pneumonia, is pneumonia in a non-intubated patient that begins 48 hours or longer after admission to hospital and was not present when they were admitted. Ventilator-associated pneumonia TABLE 30.2 Organisms Causing Pneumonia Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) Typical • Escherichia coli • Haemophilus influenzaea • Klebsiella pneumoniaea • Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) • Moraxella catarrhalis • Pseudomonas • Staphylococcus aureusa • Streptococcus pneumoniaea Atypical • Chlamydophila pneumoniae • Coxiella burnettii • Influenza A and B • Legionella pneumophilia • Mycoplasma pneumoniae • Mycobacterium tuberculosis Respiratory Viruses • Parainfluenza virus • Respiratory syncytial virus • Rhinovirus Other Causes of CAP • Fungi • Oral anaerobes Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP) • Escherichia colib • Haemophilus influenzae • Klebsiella pneumoniaeb • Microaspiration of bacteria that colonize the mouth, oropharynx • Pseudomonas aeruginosab • Proteus species • Serratia marcescens • Staphylococcus aureus • Streptococcus pneumoniaea aMost common cause of CAP. bMost common causes of HAP. CHAPTER 30 TABLE 30.3 Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) The PSI can supplement clinical judgment to determine the severity of pneumonia and if patients need to be hospitalized. Factor Points Demographics Age in years Women Extended care resident – 10 +10 Other Conditions Stroke, kidney disease, heart failure Active cancer Liver disease +10 each +30 +20 Assessment Respiratory rate ≥30/min, BP < 90, altered mental status Pulse 125/min Temperature <95°F (35°C) or ≥104°F (4O°C) Pleural effusion +20 each +10 +15 +10 Laboratory Results pH < 7.35 BUN ≥30 mg/dL, Sodium <130 mEq/L Glucose 250 mg/dL, Hematocrit < 30%, pAO2 <60 mm Hg or O2 <90 percent Scoring: <70 points 71-90 points >91 points +30 +20 each +10 each Outpatient Outpatient vs. Observation Inpatient Source: Community-acquired pneumonia severity index (PSI) for adults. Retrieved from https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/tools/calculators/calculator/77-s2.0-99. (VAP), a type of HAP, refers to pneumonia that occurs more than 48 hours after endotracheal intubation.6 VAP is discussed in Chapter 28. Both HAP and VAP are associated with longer hospital stays, increased associated costs, sicker patients, and increased mortality. Once the diagnosis of CAP, HAP, or VAP is made, treatment is started based on risk factors, speed of onset, clinical presentation, underlying medical conditions, hemodynamic stability, and the most likely causative pathogen. Empiric antibiotic therapy, the initiation of treatment before a definitive diagnosis or causative agent is made, should be started as soon as pneumonia is suspected. Empiric antibiotic therapy is based on the drugs known to be effective for the most likely cause. Antibiotic therapy is adjusted once the results of sputum cultures identify the exact pathogen causing the infection. Types of Pneumonia There are several types of pneumonia. Viral pneumonia is the most common type. It occurs in one third of all pneumonia cases. It may be mild and self-limiting or cause potentially life-threatening problems, such as acute respiratory failure (ARF) in influenza. Patients with bacterial pneumonia may be extremely unwell and need hospital admission. Mycoplasma Lower Respiratory Problems 599 pneumonia, which has traits of both bacteria and viruses, is often called “atypical” pneumonia. It is mild and occurs in persons younger than 40 years of age. Aspiration Pneumonia Aspiration pneumonia results from the abnormal entry of material from the mouth or stomach into the trachea and lungs. Conditions that increase the risk for aspiration include decreased level of consciousness (e.g., seizure, anesthesia, head injury, stroke, alcohol use), swallowing problems, and having a nasogastric (NG) tube with or without enteral feeding. With loss of consciousness, the gag and cough reflexes are depressed, making aspiration more likely. The aspirated material (food, water, vomitus, oropharyngeal secretions) triggers an inflammatory response. The most common form of aspiration pneumonia is a primary bacterial infection. Typically, the sputum culture shows more than 1 organism, including aerobes and anaerobes, since they both make up the flora of the oropharynx. Until cultures are done and results obtained, initial antibiotic therapy is based on an assessment of probable cause, severity of illness, and patient factors (e.g., malnutrition, current use of antibiotic therapy). For patients who aspirate in hospitals, antibiotic coverage should include both gram-negative organisms and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Aspiration of acidic gastric contents can cause chemical (noninfectious) pneumonitis, which may not need antibiotic therapy. However, secondary bacterial infection can occur in these patients 48 to 72 hours later. Necrotizing Pneumonia Necrotizing pneumonia is a rare complication of bacterial lung infection. It causes the lung tissue to turn into a thick, liquid mass. Cavitation and lung abscesses can occur. This sometimes happens with CAP. We do not know the exact mechanisms involved. Common causative organisms include Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, and Streptococcus. Signs and symptoms include respiratory insufficiency and/or failure, leukocytosis, and abnormalities on chest imaging.7 Treatment includes long-term antibiotic therapy and possible surgery. Opportunistic Pneumonia Opportunistic pneumonia is inflammation and infection of the lower respiratory tract in immunocompromised patients. Persons at risk include those with altered immune responses. This can include people with severe protein-calorie malnutrition or immunodeficiencies (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection) and those receiving radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and any immunosuppressive therapy, including long-term corticosteroid therapy. In addition to the risk for bacterial and viral pneumonia, the immunocompromised person may develop an infection from organisms that do not normally cause disease, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP) or cytomegalovirus (CMV).8 PJP is occurring with greater frequency in HIV-negative, immunocompromised persons.8 The onset is slow and subtle. Symptoms include fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, dyspnea, 600 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Inflammatory response • Attraction of neutrophils • Release of inflammatory mediators • Accumulation of fibrinous exudates, red blood cells, and bacteria Alveoli fill with fluid and debris (consolidation) Increased production of mucus (airway obstruction) Decreased gas exchange A A A B Fig. 30.2 Atelectasis. Scanning electron micrograph of lung parenchyma. (A) Alveoli (A) and alveolar-capillary membrane (arrow). (B) Effects of atelectasis. Alveoli (A) are partially or totally collapsed. (A, From Dantzker DR, Bone RC, George RB, editors: Pulmonary and critical care medicine, vol 1, St Louis, 1993, Mosby. B, From Albertine KH, Williams MC, Hyde DM: Anatomy of the lungs. In RJ Mason, VC Broaddus, JF Murray, et al., editors: Murray and Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.) Resolution of infection • Macrophages in alveoli ingest and remove debris • Normal lung tissue restored • Gas exchange returns to normal Fig. 30.1 Pathophysiologic course of pneumonia. nonproductive cough, and hypoxemia. The chest x-ray usually shows diffuse bilateral infiltrates. In widespread disease, the lungs have massive consolidation. PJP can be life-threatening, causing ARF and death. Infection can spread to other organs, including the liver, bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, and thyroid. Bacterial and viral pneumonias first must be ruled out because of the vague presentation of PJP. Although the causative agent is fungal, PJP does not respond to antifungal agents. Treatment consists of IV or oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, depending on the severity of disease, overall clinical condition, and the patient’s response. CMV, a herpes virus, can cause viral pneumonia. Most CMV infections are asymptomatic or mild. Severe disease can occur in people with an impaired immune response. CMV is one of the most important life-threatening infectious complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.9 Antiviral medications (e.g., ganciclovir, cidofovir) and high-dose immunoglobulin are part of treatment. Pathophysiology Specific pathophysiologic changes related to pneumonia vary depending on the offending pathogen. Almost all pathogens trigger an inflammatory response in the lungs (Fig. 30.1). Inflammation, characterized by an increase in blood flow and vascular permeability, activates neutrophils to engulf and kill the offending pathogens. As a result, the inflammatory process attracts more neutrophils, airway edema occurs, and fluid leaks from the capillaries and tissues into alveoli. Normal O2 transport is affected, leading to manifestations of hypoxia (e.g., tachypnea, dyspnea, tachycardia). Atelectasis, the absence of gas or air in 1 or more areas of the lung, may occur with pneumonia (Fig. 30.2). Atelectasis may be asymptomatic. Some patients have extreme shortness of breath and severe chest pain. Consolidation, a feature typical of bacterial pneumonia, occurs when the normally air-filled Fig. 30.3 Chest x-ray of a patient with acute bacterial pneumonia. (© iStock.com/stockdevil.) alveoli become filled with water, fluid, and/or debris (Fig. 30.3). This can potentially obstruct airflow, impair gas exchange, and cause significant respiratory insufficiency. Over time and with appropriate antibiotic therapy, macrophages lyse and process the debris. This allows lung tissue to recover and gas exchange to return to normal. Clinical Manifestations The most common presenting symptoms of pneumonia are cough, fever, chills, dyspnea, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain. The cough may or may not be productive. Sputum may be green, yellow, or even rust colored (bloody). Viral pneumonia may initially be seen as influenza, with respiratory symptoms appearing and/or worsening 12 to 36 hours after onset. The older or debilitated patient may not have classic symptoms of pneumonia. Confusion or stupor (possibly related to hypoxia) may be the only finding. The older adult may have CHAPTER 30 hypothermia, rather than fever. Nonspecific manifestations include diaphoresis, anorexia, fatigue, myalgias, and headache. Fine or coarse crackles may be auscultated over the affected region. If consolidation is present, bronchial breath sounds, egophony (an increase in the sound of the patient’s voice), and increased fremitus (chest wall vibrations made by vocalization) may be present. Patients with pleural effusion may have dullness to percussion over the affected area. Complications A major problem today is pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Common culprits include MRSA and gram-negative bacilli. Risk factors for MDR pneumonia include advanced age, immunosuppression, history of antibiotic use, and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Antibiotic susceptibility tests can identify MDR pathogens. The virulence of these pathogens can severely limit the available and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. MDR pathogens increase mortality from pneumonia. Other complications from pneumonia develop more often in older adults and those with underlying chronic diseases. These include: • Pleurisy, inflammation of the pleura. • Pleural effusion, or fluid in the pleural space. In most cases, the effusion is sterile and reabsorbed in 1 to 2 weeks. Sometimes, effusions require aspiration by thoracentesis. • Bacteremia, bacterial infection in the blood, is more likely to occur in infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. • Pneumothorax can occur when air collects in the pleural space, causing the lungs to collapse. • ARF is a leading cause of death in patients with severe pneumonia. ARF occurs when pneumonia damages the lungs’ ability to exchange O2 and CO2 across the alveolar-capillary membrane. • Sepsis can occur when bacteria within alveoli enter the bloodstream. Severe sepsis can lead to shock and multisystem organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (see Chapter 42). Lung abscess is not a common complication of pneumonia. It may occur with pneumonia caused by S. aureus and gram-negative organisms. Empyema, the accumulation of purulent exudate in the pleural cavity, may occur in up to 20% of cases. It requires antibiotic therapy and drainage of the exudate by a chest tube or open surgical drainage. Pleurisy, pleural effusion, and lung abscess are discussed later in this chapter. Diagnostic Studies The common diagnostic procedures for pneumonia are outlined in Table 30.4. History, physical assessment, and chest x-ray often give enough information to make immediate decisions about early treatment. Chest x-ray often shows patterns characteristic of the infecting pathogen and is important in diagnosing pneumonia. X-ray may also show pleural effusions. Bronchoscopy with bronchial washings or thoracentesis may be done to obtain cell and fluid samples from patients not responding to initial therapy. Arterial blood gases (ABGs) may show hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidosis. Leukocytosis occurs in most patients with Lower Respiratory Problems TABLE 30.4 Pneumonia 601 Interprofessional Care Diagnostic Assessment • History and physical assessment • Chest x-ray • Sputum: Gram stain, culture and sensitivity test • Pulse oximetry and/or ABGs • CBC, white blood cell differential, and routine blood chemistries • Blood cultures (if indicated) Management • O2 therapy • Critical care management, with mechanical ventilation as needed • Increased fluid intake (at least 2–3 L/day), IV fluids • VTE prophylaxis • Physiotherapy, early mobility • Balance between activity and rest Drug Therapy • Appropriate antibiotic therapy (Table 30.6) • Antipyretics • Analgesics • NSAIDs (if no contraindications) bacterial pneumonia. The white blood cell (WBC) count is usually greater than 15,000/μL (15 × 109/L) with the presence of bands (immature neutrophils). Ideally, we should obtain a sputum specimen for culture and Gram stain to identify the organism before starting antibiotic therapy. However, we should not delay starting antibiotic therapy if we cannot obtain a specimen. Delays in antibiotic therapy can increase the risk for mortality. Blood cultures are done for patients who are seriously ill. C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and interleukin 6 (IL-6) are currently being explored as ways to help tell pneumonia from other types of heart and respiratory failure.10 Interprofessional Care Prompt treatment with the appropriate antibiotic is essential. Antibiotics are highly effective for both bacterial and mycoplasma pneumonia. In uncomplicated cases, the patient responds to drug therapy within 48 to 72 hours. Signs of improvement include decreased temperature, improved breathing, and less chest discomfort. Abnormal physical findings can last more than 7 days. Pneumococcal vaccine is used to prevent S. pneumoniae infection (Table 30.5). Although cough suppressants, mucolytics, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids are often prescribed as adjunctive therapy, the use of these drugs is debatable. However, they may be prescribed for patients with underlying chronic conditions. Currently, there is no definitive treatment for most viral pneumonias. Care is generally supportive. In most circumstances, viral pneumonia is self-limiting and will often resolve in 3 to 4 days. Antiviral therapy may be used to treat pneumonia caused by influenza (e.g., oseltamivir, zanamivir) or a few other viruses (e.g., acyclovir for herpes simplex virus). Drug Therapy The HCP selects empiric therapy based on the likely pathogen. Table 30.6 presents the drug therapy for bacterial CAP. 602 SECTION 6 TABLE 30.5 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Pneumococcal Vaccines Vaccinea Recommendations for Use Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13): Protect against 13 types of pneumococcal bacteria • Children <2 years • Adults ≥65 years • Anyone 2–64 years old with certain medical conditions (e.g., sickle cell disease, asplenia, immunodeficiencies, HIV infection, chronic kidney disease, leukemia, cancer, long-term immunosuppressive therapy) • Adults ≥50 years • Adults 19–64 years old who smoke • Anyone 2–64 years old who have high risk of pneumococcal disease (e.g., heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, alcohol use, cirrhosis, sickle cell disease, immunocompromised, cancer) Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Pneumovax 23): Protect against 23 types of pneumococcal bacteria aFor more details on scheduling of pneumococcal vaccinations, see https:www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/vaccination.html. TABLE 30.6 Drug Therapy Bacterial Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patient Variable Treatment Options Outpatient Healthy No comorbidities or risk factors for antibiotic-resistant infection Beta lactam OR Macrolide OR ­doxycycline Co-Morbidities COPD; diabetes; chronic liver, lung, heart, or renal disease; cancer; alcohol use; no spleen Inpatient Medical Unit ICU Special Considerations •Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) •Pseudomonas infection •Pseudomonas infection in patient with penicillin allergy Respiratory fluoroquinolone OR β-Lactam plus macrolide (doxycycline may be substituted for macrolide) OR Beta lactam plus doxycycline plus macrolide Respiratory fluoroquinolone OR β-Lactam plus macrolide (doxycycline may be substituted for macrolide) β-Lactam plus either azithromycin or respiratory fluoroquinolone Vancomycin or linezolid (Zyvox) Antipneumococcal and antipseudomonal β-lactam OR Antipneumococcal, antipseudomonal β-lactam plus either respiratory fluoroquinolone or ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin OR Antipneumococcal, antipseudomonal β-lactam plus aminoglycoside plus either ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin Substitute aztreonam for the above β-lactam Source: Community acquired pneumonia in adults. Retrieved from https:// www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/clinical_overview/67-s2.0-77188ebde5b9-49a1-88a0-0211995a4b85#treatment-options-heading-35. For all types of pneumonia, empiric antibiotic therapy is based on whether the patient has risk factors for MDR pathogens. The prevalence and resistance patterns of MDR pathogens vary among localities and agencies. Therefore, antibiotic therapy must be adapted to local patterns of antibiotic resistance. Multiple regimens exist. All treatment should initially include antibiotics that are effective against both resistant gram-negative and resistant gram-positive organisms. Clinical improvement usually occurs in 3 to 5 days. Patients who do not respond to therapy or deteriorate need aggressive re-evaluation to assess for noninfectious causes, complications, coexisting infectious processes, or pneumonia caused by an MDR pathogen. We switch the patient from IV to oral antibiotic therapy as soon as they are improving clinically and able to take oral medication. Stable patients can be discharged on oral antibiotics. Total treatment time for patients with CAP should be a minimum of 5 days. The patient should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours before stopping treatment. Stress the importance of completing the full course of antibiotic treatment. Longer treatment time may be needed if initial therapy was not active against the identified pathogen or complications occur. Nutrition Therapy Hydration is important to prevent dehydration and thin and loosen secretions. Carefully monitor fluid intake. If the patient is an older adult, has heart failure (HF), or has a known preexisting respiratory condition, administer IV fluids carefully to avoid fluid overload. Pay close attention to intake and output. Monitor and replace electrolytes as needed. Weight loss may occur in patients with pneumonia because of increased metabolic needs, difficulty eating due to dyspnea, nonspecific abdominal symptoms, and activity intolerance. Small, frequent meals are easier for dyspneic patients to tolerate. Offer foods high in calories and nutrients. A nutrition assessment by a dietitian may be done on admission to acute care. NURSING MANAGEMENT: PNEUMONIA Assessment Table 30.7 presents subjective and objective data to obtain from a patient with pneumonia. Clinical Problems Clinical problems for the patient with pneumonia may include: • Impaired respiratory function • Infection • Fluid imbalance • Activity intolerance • Altered body temperature Additional information on clinical problems and interventions for the patient with pneumonia is shown in eNursing Care Plan 30.1 on the website for this chapter. Planning The overall goals are that the patient with pneumonia will have (1) no signs of hypoxemia, (2) normal breathing patterns, (3) clear breath sounds, (4) normal chest x-ray, (5) normal WBC count, and (6) no complications. CHAPTER 30 Lower Respiratory Problems 603 TABLE 30.7 NURSING ASSESSMENT Pneumonia TABLE 30.8 NURSING MANAGEMENT Care of the Patient With Pneumonia Subjective Data Important Health Information Health history: Lung cancer, COPD, diabetes, chronic debilitating disease, malnutrition, immunosuppression, exposure to chemical toxins, dust, or allergens Medications: Antibiotics, corticosteroids, chemotherapy, or any immunosuppressants Surgery or other treatments: Recent abdominal or chest surgery, splenectomy, endotracheal intubation, enteral feedings, or any surgery with general anesthesia. • Monitor respiratory status: •Breath sounds, noting areas of decreased or absent ventilation, and presence of adventitious sounds. •Rate, rhythm, depth, and effort of respirations. •Characteristics of any secretions. •Ability to cough effectively and presence of fatigue. •Assess for signs of hypoxemia. •Administer antibiotic and IV fluid therapy as ordered. •Administer medications (e.g., bronchodilators and inhalers) to promote airway patency and gas exchange. •Keep the head of the bed elevated at least 30 degrees. •Turn and reposition the patient every 2 hrs to promote lung expansion and mobilize secretions. •Encourage the patient to cough, deep breathe, and use the incentive spirometer. •Implement measures to manage fever (see Table 12.5). •Administer analgesics as ordered to relieve pain. •Provide ordered VTE and GI prophylaxis. •Monitor intake and output. •Supervise AP: •Obtain vital signs and report to RN. •Provide personal hygiene, skin care, and oral care •Assist with frequent position changes, including early mobility •Report to RN any change in patient condition. Functional Health Patterns Health perception–health management: Smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, recent tract URI, malaise Nutritional-metabolic: Anorexia, nausea, vomiting Activity-exercise: Prolonged bed rest or immobility. Fatigue, weakness. Dyspnea, cough. Cognitive-perceptual: Pain with breathing, nasal congestion, chest pain, sore throat, headache, abdominal pain, muscle aches Objective Data Cardiovascular •Tachycardia General •Fever, restlessness, or lethargy. Splinting of thoracic cavity Neurologic •Changes in mental status, ranging from confusion to delirium Respiratory •Tachypnea, pharyngitis •Asymmetric chest movements or retraction, decreased excursion •Nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles (neck, abdomen) •Crackles, friction rub on auscultation, dullness on percussion over consolidated areas, ↑ tactile fremitus on palpation •Pink, rusty, purulent, green, yellow, or white sputum (amount may be scant to copious) Possible Diagnostic Findings •Leukocytosis, positive sputum on Gram stain and culture, Patchy or diffuse infiltrates, abscesses, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax on chest x-ray •leftAbnormal ABGs with ↓ or normal PaO2, ↓ or normal PaCO2, and ↑ or normal pH initially, and later ↓ PaO2, ↑ PaCO2, and ↓ pH Implementation Health Promotion To reduce the risk for pneumonia, teach patients to practice good health habits, such as frequent hand washing, good nutrition, adequate rest, regular exercise, and coughing or sneezing into the elbow rather than hands. Avoiding smoking is one of the most important health-promoting behaviors. If possible, avoid exposure to people with URIs. If a URI occurs, it requires prompt attention with supportive measures (e.g., rest, fluids). If symptoms persist for longer than 7 days, the person should seek medical care. Identifying patients at risk and taking measures to prevent pneumonia are important. Encourage those at risk for pneumonia (e.g., chronically ill, older adult) to obtain needed vaccines. Collaborate With Respiratory Therapist •Apply O2 therapy as ordered. •Perform chest physiotherapy (e.g., percussion, postural drainage). Collaborate With Dietitian •Assess and monitor nutrition status. •Recommend optimal diet. Collaborate With Physical and Occupational Therapist •Perform ROM exercises. •Assist with early and progressive ambulation. Acute Care Nursing care for the patient with pneumonia is outlined in Table 30.8. Although many patients with pneumonia are treated on an outpatient basis, the nursing care plan for a patient with pneumonia (see eNursing Care Plan 30.1) applies to both patients at home and hospitalized. Essential nursing care for hospitalized patients with pneumonia includes monitoring assessment findings and the response to therapy. We provide supportive measures according to the patient’s needs. These may include O2 therapy to treat hypoxemia and analgesics to relieve chest pain. Implement measures to reduce fever (see Table 12.5). Prompt collection of specimens and timely administration of antibiotics is critical. Hydration, nutrition support, and positioning are part of the care plan. Work with the respiratory therapist to monitor the patient’s condition and provide chest physiotherapy. Balance rest and activity to each patient’s tolerance. Benefits of early mobility include improved lung and chest expansion, mobilization of secretions, and prevention of venous stasis. 604 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Practice strict medical asepsis and adherence to infection control guidelines to reduce the incidence of possible transmission between staff and patients. Staff and visitors should wash their hands when entering and leaving the patient’s room. Staff must wash hands or use hand sanitizer before and after providing care and on removing gloves. Implement measures to reduce the incidence of pneumonia in patients at higher risk. To prevent aspiration in the patient who has problems swallowing, elevate the head-of-bed to at least 30 degrees. Assess for presence of a gag reflex before giving food or fluids. Patients who have an orogastric or NG tube are at risk for aspiration pneumonia. Although feeding tubes are small, any interruption in the integrity of the lower esophageal sphincter can allow reflux of gastric contents. Elevating the head of the bed can help prevent this complication. After surgery, treat pain to a comfort level that permits the patient to deep breathe and cough yet remain awake and alert and achieve optimum mobility. Twice-daily oral hygiene with chlorhexidine swabs reduces the risk of pneumonia in postoperative patients.11 In the ICU, strictly adhere to the ventilator bundle (see Table 28.10), a group of interventions aimed at reducing the risk for VAP. Maintain sterile aseptic technique when suctioning the patient’s trachea. Use caution when handling ventilator circuits, tracheostomy tubing, and nebulizer circuits that can become contaminated from patient secretions. Ambulatory Care Teach the patient about the importance of taking every dose of the prescribed antibiotic (see Table 15.9). Review any drug-drug and food-drug interactions. Explain the need for adequate rest to promote recovery. Tell the patient to drink plenty of liquids (at least 6 to 10 glasses/day, unless contraindicated) and avoid alcohol and smoking. A cool mist humidifier or warm bath may help the patient breathe easier. Tell them that it may be several weeks before their usual sense of well-being returns. Explain that a follow-up chest x-ray may be done in 6 to 8 weeks to evaluate resolution of pneumonia. The older adult or chronically ill patient may have a prolonged period of convalescence. Teaching should include information about available influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Patients can receive the pneumococcal vaccine and influenza vaccine at the same time but not in the exact same location. The vaccines cannot be mixed into 1 injection. Evaluation The expected outcomes are that the patient with pneumonia will have: • Effective respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth of respirations • Lungs clear to auscultation • No complications TUBERCULOSIS Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It usually involves the lungs, but can infect any organ, including the brain, kidneys, and bones. BOX 30.2 EQUITY PROMOTING HEALTH Tuberculosis • 88% of TB cases in the United States occur in racial and ethnic minorities. 71.4% of these persons were born outside of the United States. • Asians have the highest TB rate, followed by Hispanics (30%) and Blacks (20%). • American Indian/Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders have the lowest TB rates amongst all ethnic groups (1%). Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health disparities in TB. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/default. htm. About 25% of the world’s population is infected with TB.12 The incidence of TB worldwide declined until the mid-1980s. We are now seeing increasing rates of TB. This is attributed to HIV disease and the emergence of drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis. TB is the leading cause of mortality in patients with HIV infection. TB occurs disproportionately in the poor, underserved, and minorities (Box 30.2). People most at risk include the homeless, residents of inner-city neighborhoods, foreign-born people, those living or working in institutions (long-term care facilities, prisons, shelters, hospitals), IV drug users, overcrowded living conditions, less than optimal sanitation, and those with poor access to health care. Immunosuppression from any cause (e.g., HIV infection, cancer, long-term corticosteroid use) increases the risk for active TB infection. Etiology and Pathophysiology M. tuberculosis is a gram-positive, aerobic, acid-fast bacillus (AFB). It is usually spread from person to person by airborne droplets expectorated when breathing, talking, singing, sneezing, and coughing. A process of evaporation leaves small droplet nuclei, 1 to 5 μm in size, suspended in the air for minutes to hours. Another person then inhales the bacteria. Humans are the only known reservoir for TB. TB is not highly infectious. Transmission requires close contact and frequent or prolonged exposure. TB does not spread by touching, sharing food utensils, kissing, or any other physical contact. Factors that influence transmission include the (1) number of organisms expelled into the air, (2) concentration of organisms (small spaces with limited ventilation would mean higher concentration), (3) length of time of exposure, and (4) immune system of the exposed person. Once inhaled, these small droplets lodge in bronchioles and alveoli. A local inflammatory reaction occurs, and the infection is established. This is called the Ghon lesion or focus. It represents a calcified TB granuloma, the hallmark of a primary TB infection. The formation of a granuloma is a defense mechanism aimed at walling off the infection and preventing further spread. Bacillus replication is inhibited, stopping the infection. Most immunocompetent adults infected with TB can completely kill the mycobacteria. Some people have the mycobacteria in a non-replicating dormant state. Of these persons, 5% to 10% develop active TB infection when the bacteria begin to CHAPTER 30 TABLE 30.9 Classification of Tuberculosis Class Exposure or Infection 0 No TB exposure 1 TB exposure, no infection Latent TB infection, no disease 2 3 TB, clinically active 4 TB, but not clinically active 5 TB suspect Lower Respiratory Problems 605 Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) Compared to Tuberculosis Disease TABLE 30.10 Description LTBI TB Disease No TB exposure, not infected (no history of exposure, negative tuberculin skin test) TB exposure, no evidence of infection (history of exposure, negative tuberculin skin test) TB infection without disease (positive reaction to tuberculin skin test, negative bacteriologic studies, no x-ray findings compatible with TB, no clinical evidence of TB) TB infection with clinically active disease (positive bacteriologic studies or both a significant reaction to tuberculin skin test and clinical or x-ray evidence of current disease) No current disease (history of previous episode of TB or abnormal, stable x-ray findings in a person with a positive reaction to tuberculin skin test. Negative bacteriologic studies if done. No clinical or x-ray evidence of current disease) TB suspect (diagnosis pending). Person should not be in this classification for >3 months Has no symptoms Has symptoms that may include: • Bad cough that lasts ≥3 week • Pain in the chest • Coughing up blood or sputum • Weakness or fatigue • Weight loss, no appetite • Chills • Fever • Sweating at night Usually feels sick May spread TB bacteria to others Usually has a positive TST or blood test result showing TB infection May have an abnormal chest x-ray or positive sputum smear or culture Needs treatment for active TB disease multiply months or years later. While M. tuberculosis is aerophilic (O2 loving) and has an affinity for the lungs, the infection can spread through the lymphatic system and find good environments for growth in other organs. These include the cerebral cortex, spine, bone epiphyses, liver, kidneys, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands. Once a strain of M. tuberculosis develops resistance to the first-line drug therapy (isoniazid and rifampin), it is defined as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).13 Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) is a rare type of MDR-TB. XDR-TB is also resistant to any fluoroquinolone and at least 1 second-line drug.13 Resistance results from several problems, including incorrect prescribing, lack of case management, and nonadherence to the prescribed regimen. Classification We use several systems to classify TB. The American Thoracic Society classifies TB based on disease development (Table 30.9). We also classify TB by (1) its presentation (primary, latent, reactivated) and (2) whether it is pulmonary or extrapulmonary. Primary TB infection starts when the bacteria are inhaled and trigger an inflammatory reaction. Most people have effective immune responses that encapsulate the organisms for the rest of their lives, preventing the initial infection from progressing to disease. If the initial immune response is not adequate, the body cannot contain the organism. As a result, the bacteria replicate and active TB disease results. When active disease develops within the first 2 years of infection, it is called primary TB. People co-infected with HIV are at greatest risk for developing active TB. Post-primary TB, or reactivation TB, is defined as TB disease occurring 2 or more years after the initial infection. If the site of Does not feel sick Cannot spread TB bacteria to others Usually has a positive TST or blood test result showing TB infection Has a normal chest x-ray and a negative sputum smear Needs treatment for latent TB infection to prevent active TB disease Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis (TB) fact sheets: the difference between latent TB infection and TB disease. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/ general/ltbiandactivetb.htm. TB is pulmonary or laryngeal, the person is infectious and can transmit the disease to others. Latent TB infection (LTBI) occurs in a person who does not have active TB disease (Table 30.10). People with LTBI have a positive skin test but are asymptomatic. They cannot transmit the TB bacteria to others but can develop active TB disease later. Immunosuppression, diabetes, poor nutrition, HIV, glucocorticoid therapy, pregnancy, stress, and chronic disease can reactivate the disease. Treatment of LTBI is as important as primary TB. Clinical Manifestations Symptoms of pulmonary TB usually do not develop until 2 to 3 weeks after infection or reactivation. The primary manifestation is an initial dry cough. It often becomes productive with mucoid or mucopurulent sputum. Active TB disease may initially present with constitutional symptoms (e.g., fatigue, malaise, anorexia, unexplained weight loss, low-grade fevers, night sweats). Dyspnea is a late symptom that may signify considerable pulmonary disease or a pleural effusion. Hemoptysis is also a late symptom. Sometimes, TB has a more acute, sudden presentation. The patient may have a high fever, chills, flu-like symptoms, pleuritic pain, a productive cough, and ARF. Lung auscultation may be normal or reveal adventitious sounds, such as crackles. Hypotension and hypoxemia may be present. Immunosuppressed (e.g., HIV-infected) people and older adults are less likely to have fever and other signs of an infection. In patients with HIV, classic manifestations of TB, such as fever, cough, and weight loss, may be wrongly attributed to PJP or other HIV-associated opportunistic diseases. Respiratory problems in patients with HIV are assessed to determine the 606 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation cause. A change in cognitive function may be the only initial presenting sign of TB in an older person. The manifestations of extrapulmonary TB depend on the organs infected. For example, renal TB can cause dysuria and hematuria. Bone and joint TB may cause severe pain. Headaches, vomiting, and lymphadenopathy may be present with TB meningitis. Complications Properly treated, pulmonary TB typically heals without complications, except for scarring and residual cavitation within the lung. Significant lung damage, although rare, can occur in patients who are poorly treated or who do not respond to TB treatment. Miliary TB is widespread dissemination of the mycobacterium through the bloodstream to several distant organs. The infection is characterized by a large amount of TB bacilli and may be fatal if untreated. It can occur with primary disease or reactivation of LTBI. Manifestations slowly progress over a period of days, weeks, or even months. Symptoms vary depending on the organs that are affected. Fever, cough, and lymphadenopathy are present. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may occur. Pleural TB, a specific type of extrapulmonary TB, can result from either primary disease or reactivation of a latent infection. Chest pain, fever, cough, and a unilateral pleural effusion are common. A pleural effusion is caused by bacteria in the pleural space, which trigger an inflammatory reaction and a pleural exudate of protein-rich fluid. Empyema is less common than effusion but may occur from large numbers of TB organisms in the pleural space. Diagnosis is confirmed by AFB cultures and a pleural biopsy. Because TB can infect organs throughout the body, other acute and long-term complications can result. TB in the spine (Pott disease) can lead to destruction of the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebrae. Central nervous system (CNS) TB can cause bacterial meningitis. Abdominal TB can lead to peritonitis, especially in HIV-positive patients. The kidneys, adrenal glands, lymph nodes, and urogenital tract can be affected. Diagnostic Studies Tuberculin Skin Test The tuberculin skin test (TST) (Mantoux test) using purified protein derivative (PPD) is the standard method to screen people for M. tuberculosis. The test is given by injecting 0.1 mL of PPD intradermally on the ventral surface of the forearm. We read the test by inspection and palpation 48 to 72 hours later for the presence or absence of induration. Induration, a palpable, raised, hardened area or swelling (not redness) at the injection site means the person has been exposed to TB and has developed antibodies. Antibody formation occurs 2 to 12 weeks after initial exposure to the bacteria. Any indurated area present is measured and recorded in millimeters. Based on the size of the induration and risk factors, we make an interpretation based on CDC standards for determining a positive test (see Table 27.15). Two-step testing with the Mantoux test is recommended for baseline or initial screening for health care workers and those who have a decreased response to allergens. If the 1st test is positive, the person does not need the 2nd test. They do, however, need further evaluation for active disease. If the 1st test is negative, a 2nd test is done 1 to 3 weeks later. Some people with LTBI or who were previously infected with TB may have a falsenegative result with the 1st test. Repeating the test may stimulate (boost) the body’s ability to react in future tests.14 A positive reaction to a subsequent test could be a new infection or the result of the boosted reaction to an old infection. A previously negative 2 step test ensures that any future positive results can be accurately interpreted as being caused by a new infection. Interferon-γ Release Assays Interferon-γ (INF-γ) release assays (IGRAs) are another screening tool for TB. IGRAs are blood tests that detect INF-γ release from T cells in response to M. tuberculosis.15 Examples of IGRAs include QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT.TB test. Test results are available in a few hours. IGRAs have several advantages over the TST. IGRAs require only 1 patient visit, are not subject to reader bias, have no “booster” phenomenon, and are not affected by bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. The cost of an IGRA is much higher than the TST. Guidelines suggest that both tests are viable options. The choice should be based on context and reasons for testing. Neither IGRAs nor TST can tell between LTBI and active TB infection. LTBI can only be diagnosed by excluding active TB. Chest X-Ray Although the chest x-ray findings are important, it is not possible to make a diagnosis of TB based solely on chest x-ray findings. The chest x-ray may appear normal in a patient with TB. Findings suggestive of TB include upper lobe infiltrates, cavitary infiltrates, lymph node involvement, and pleural and/ or pericardial effusion. Other diseases, such as sarcoidosis, can mimic the appearance of TB. Bacteriologic Studies Sputum culture is the gold standard for diagnosing TB. We need 3 consecutive sputum specimens, each collected at 8- to 24-hour intervals, with at least 1 early morning specimen. The initial test involves microscopic examination of stained sputum smears for AFB. A definitive diagnosis of TB requires mycobacterial growth, which can take up to 6 weeks. For patients in whom suspicion of TB is high, treatment is started while waiting for culture results. Samples for other suspected TB sites can be collected from gastric washings, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or fluid from an effusion or abscess. Interprofessional Care Most patients with TB are treated on an outpatient basis (Table 30.11). Many people can continue to work and maintain their lifestyles with few changes. Patients with sputum smear–positive TB are considered infectious for the first 2 weeks after starting treatment. Advise these patients to restrict visitors, and avoid travel, public transportation, and trips to public places. Teach them the importance of good hand washing and oral CHAPTER 30 Lower Respiratory Problems TABLE 30.11 Interprofessional Care Pulmonary Tuberculosis TABLE 30.12 Tuberculosis Diagnostic Assessment • History and physical assessment • Tuberculin skin test (TST) • QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) or T-SPOT.TB test • Chest x-ray • Bacteriologic studies • Sputum smear for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) • Sputum culture Drug Management • Long-term treatment with antimicrobial drugs (Tables 30.12 and 30.13) • Follow-up AFB smears, cultures, and chest x-rays • Follow-up care, addressing needs and concerns of patient and close contacts, and involving community health care workers and social workers hygiene. Hospitalization may be needed for the severely ill or debilitated patient. Drug Therapy Active disease. The mainstay of TB treatment is drug therapy (Table 30.12). Because of the growing prevalence of MDR-TB, it is important to manage the patient with active TB aggressively. Drug therapy is divided into 2 phases: intensive and continuation (Table 30.13). In most circumstances the treatment regimen for patients with previously untreated TB consists of a plan with 4 drugs (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol). If drug susceptibility test results show that the bacteria are susceptible to all drugs, ethambutol may be stopped. If the patient develops a toxic reaction to the primary drugs, other drugs can be used, including rifabutin and rifapentine (Priftin). If pyrazinamide is not included in the initial phase (e.g., liver disease, pregnancy), the remaining 3 drugs are used for the initial phase. DRUG ALERT Drug Therapy For Active TB ethambutol (Myambutol) isoniazid pyrazinamide rifampin For Drug Resistant TB Fluoroquinolones •levofloxacin •moxifloxacin Injectable antibiotics Aminoglycosides •amikacin •capreomycin (Capastat) •kanamycin bedaquiline (Sirturo) pretomanid streptomycin 607 Common Side Effects Headache, blurred vision, ocular toxicity (decreased red-green color discrimination) Liver toxicity, asymptomatic elevation of aminotransferases (ALT, AST) Vomiting, confusion, headache Liver toxicity, joint pain, hyperuricemia Liver toxicity, thrombocytopenia Orange discoloration of bodily fluids (sputum, urine, sweat, tears) Anorexia, nausea, abdominal discomfort GI problems, neurologic effects (dizziness, headache), rash Hepatitis, GI toxicity Prolonged QT interval Ototoxicity, kidney toxicity Liver toxicity, nausea Joint and muscle pain Nausea, vomiting, liver problems Peripheral neuropathy Vision problems Nausea, vomiting, liver problems Ototoxicity, neurotoxicity, kidney toxicity Other Drugs Used in TB rifabutin (Mycobutin) (for Liver toxicity, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia TB and co-existing HIV Orange discoloration of bodily fluids (sputum, infection) urine, sweat, tears) Nausea, vomiting, anorexia rifapentine (Priftin) (as an Like those of rifampin alternate to rifampin) Isoniazid ALT, Alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase. • Alcohol may increase risk for liver toxicity. • Teach patient to avoid drinking alcohol during treatment. • Monitor for signs of hepatitis before and while taking drug. for nonadherence.16 DOT is an expensive but essential public health measure. In many areas, the public health nurse administers DOT at a clinic site. Fixed-dose combination drugs may enhance adherence. Combinations of isoniazid and rifampin and of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide are available to simplify therapy. The therapy for people with HIV uses the same medications as outlined in Table 30.13, but in a slightly different schedule. In the intensive phase, HIV patients take isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and a rifamycin for the 1st 2 months, then isoniazid and a rifamycin for the last 4 months.17 Teach patients about the adverse effects of drug therapy and when to seek medical care. The major side effect of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide is nonviral hepatitis. Baseline liver function tests (LFTs) are done at the start of treatment and monitored closely (e.g., every 2 to 4 weeks), especially if results are abnormal. Latent tuberculosis infection. In people with LTBI, drug therapy helps prevent a TB infection from developing into active Sensitivity testing guides the treatment for MDR-TB. MDR-TB therapy in the initial phase typically includes 5 drugs: 1 or 2 first-line agents, a fluoroquinolone, an injectable antibiotic, and 1 or more second-line agents, for at least 6 months after sputum culture is negative. This is followed by at least 4 drugs, minus the injectable antibiotic, for 18 to 24 months. Two newer drugs, bedaquiline (Sirturo) and Delamanid (Deltyba), are used in combination with other drugs to treat MDR-TB and XDR-TB. Many people do not adhere to the treatment program and complete the full course of therapy (Box 30.3). Nonadherence is a major factor in the emergence of MDR-TB and treatment failures. Directly observed therapy (DOT) involves providing the antitubercular drugs directly to patients and watching as they swallow the drugs. It is the preferred way to ensure adherence for all patients with TB, especially for those at risk 608 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation TABLE 30.13 Drug Therapy Tuberculosis Treatment Regimens BOX 30.3 ETHICAL/LEGAL DILEMMAS Patient Adherence Intensive TB Medication Phase (2 Months) Continuation TB Medication Phase (4 or 7 Months) Option #1: Preferred Method 4 drugs: Daily for 8 weeks isoniazid (40–56 doses) rifampin pyrazinamide ethambutola 2 drugs: isoniazid rifampin Daily for 18 weeks (90–126 doses) OR 3 times weekly for 18 weeks (54 doses)b Alternative TB Drug Dosing—Option #1 4 drugs: Daily for 2 weeks 2 drugs: 3 times weekly for isoniazid (14 doses), then isoni18 weeks (54 rifampin 3 times per azid doses)b pyrazinamide week for 6 rifamethambutola weeks (18 pin doses)b Alternative TB Drug Dosing—Option #2 4 drugs: 3 times weekly 2 drugs: 3 times weekly for isoniazid for 8 weeks (24 isoni18 weeks (54 rifampin doses)b azid doses)b pyrazinamide rifamethambutola pin aEthambutol may be stopped if drug tests confirm susceptibility to first line drugs bAny patient receiving TB medication less than 7 days/week must receive directly observed therapy (DOT). Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Tuberculosis (TB) fact sheet: general considerations for treatment of TB disease. Retrieved from https://www. cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/treatment/treatmenthivnegative.htm. TB disease. Because a person with LTBI has fewer bacteria, treatment is much easier. Usually only 1 drug is needed. Drug regimens for LTBI are outlined in Table 30.14. The standard treatment regimen for LTBI is 9 months of daily isoniazid. It is an effective and inexpensive drug that the patient can take orally. This plan is also recommended for patients with HIV and those with fibrotic lesions on chest x-ray. While the 9-month plan is more effective, adherence issues may make a 6-month plan preferable. An alternative 3-month regimen of isoniazid and rifapentine may be used for otherwise healthy patients who we presume are not infected with MDR bacilli. Patients who are resistant to isoniazid may receive 4-month therapy with rifampin. Because of severe liver injury and deaths, the CDC does not recommend the combination of rifampin and pyrazinamide for treatment of LTBI. Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine. Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is a live, attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis. The vaccine is given to infants in parts of the world with a high prevalence of TB. In the United States, it is t rarely used because of the low risk for infection, the vaccine’s variable effectiveness against adult pulmonary TB, and potential interference with TST reactivity. The BCG vaccination can result in a false-positive TST. IGRA results are not affected. The BCG Situation While working at a health clinic at a homeless shelter, you discover that F.C., a 64-year-old man with tuberculosis (TB), has not been taking his drug therapy. He tells you that it is hard for him to get to the clinic to obtain his medications, much less to keep on a schedule. You are concerned about F.C. and the risk he poses for the other people at the shelter, in the park, and at the meal sites where he often visits. Ethical/Legal Points for Consideration • Adherence is a complex issue involving a person’s culture, values, and beliefs, perceived risk for disease, access to treatment, availability of resources, and perceived consequences of failure to adhere to treatment. • State emergency detention laws provide public health officials with the legal authority to take action to apprehend and hold a person with TB who we believe to be a threat to public health. • The federal government and many states have provisions for quarantine, detention, and treatment of patients with TB who do not adhere to treatment. • Advocacy for both the patient and the community obliges you to involve other health care team members, such as social services, to aid in obtaining resources or support for the patient to complete a course of treatment. • With the threats of bioterrorism and the globalization of infectious disease, it seems unlikely that the government’s power to detain will change anytime soon. Discussion Questions 1. How would you begin your initial conversation with F.C. about your concerns? 2. What alternatives of care can we offer to F.C.? 3. Under what circumstances, if any, are HCPs justified in overriding a patient’s autonomy or decision making? Source: Kavanagh MM, Gostin LO, Stephens J: Tuberculosis, human rights, and law reform: addressing the lack of progress in the global tuberculosis response. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003324. TABLE 30.14 LTBI Regimens Drug isoniazid and rifapentine (preferred method) rifampin isoniazid and rifampin isoniazid isoniazid Drug Therapy Duration (Months/ Weeks) Interval Number of Doses (Minimum) 3 months (12 weeks) Once weeklya 12 4 months (16 weeks) 3 months (12 weeks) 6 months (24 weeks) 9 months (36 weeks) Daily 112 Daily 84 Daily 168 Daily 252 aUse directly observed therapy (DOT). Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis (TB): treatment regimens for latent tuberculosis infections (LTBI). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. CHAPTER 30 vaccine should be considered only for select persons who meet specific criteria (e.g., health care workers who are continually exposed to patients with MDR-TB and when infection control precautions are not successful). NURSING MANAGEMENT: TUBERCULOSIS Assessment Ask the patient about a previous history of TB, chronic illness, or any immunosuppressive disease or medications. Obtain a social and occupational history to determine risk factors for TB transmission. Assess the patient for productive cough, night sweats, fever, weight loss, pleuritic chest pain, and abnormal lung sounds. If the patient has a productive cough, early morning is the best time to collect sputum specimens for an AFB smear. Clinical Problems Clinical problems for the patient with TB may include: • Impaired respiratory function • Infection • Deficient knowledge • Lack of knowledge Planning The overall goals are that the patient with TB will (1) have normal lung function, (2) adhere to the treatment plan, (3) take measures to prevent the spread of TB, and (4) have no recurrence. Implementation Health Promotion The goal is to eradicate TB worldwide. Screening programs in known risk groups are valuable in detecting persons with TB. For example, the person with a positive TST should have a chest x-ray to assess for active TB disease. Report people diagnosed with TB to public health authorities for identification and assessment of contacts and risk to the community. Treatment of LTBI reduces the number of TB carriers in the community. Programs to address the social determinants of TB are needed to decrease TB transmission. Reducing HIV infection, poverty, overcrowded living conditions, malnutrition, smoking, and drug and alcohol use can help minimize TB infection rates. Improving access to health care and education are important. Acute Care Patients admitted to the ED or directly to the unit with respiratory symptoms should be assessed for the possibility of TB. Those strongly suspected of having TB should (1) be placed on airborne isolation; (2) receive a medical workup, including chest x-ray, sputum smear and culture; and (3) start appropriate drug therapy. Airborne infection isolation is needed for the patient with pulmonary or laryngeal TB until the patient is not infectious. Patients should be placed in a single-occupancy room with negative pressure and airflow of 6 to 12 exchanges per hour. Everyone entering the room should wear a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) or N95 mask. Teach patients to cover the nose and mouth with paper tissues every time they cough, sneeze, or produce sputum. The Lower Respiratory Problems 609 tissues should be thrown into a paper bag and disposed of with the trash or flushed down the toilet. Emphasize careful hand washing after handling sputum and soiled tissues. If patients need to be out of the negative-pressure room, they must wear a standard surgical mask to prevent exposure to others. Minimize prolonged visitation to other parts of the hospital. Identify and screen close contacts of the person with TB. Anyone testing positive for TB infection needs further evaluation and treatment for either LTBI or active TB disease. Ambulatory Care Patients who respond clinically are discharged home if their household contacts have already been exposed and the patient is not posing a risk to others. A sputum specimen for AFB smear and culture should be done monthly until 2 consecutive specimen cultures are negative. More frequent AFB smears may be done to assess the early response to treatment and determine infectiousness. Negative cultures are needed to declare the patient not infectious. Teach the patient how to minimize exposure to close contacts and household members. Homes should be well ventilated, especially the areas where the infected person spends a lot of time. While still infectious, the patient should sleep alone and spend as much time as possible outdoors. Teach them to minimize time in congregate settings and public transportation. Teach the patient and caregiver about adherence with the treatment plan. Most treatment failures occur because the patient does not take the drug, stops taking it too soon, or takes it irregularly. Strategies to improve adherence include teaching and counseling, reminder systems, incentives or rewards, contracts, and DOT. Notify the public health department. They are responsible for follow-up on household contacts and assessing the patient for adherence. If adherence is an issue, the public health department may be responsible for DOT (Box 30.4). Most patients are considered adequately treated when drug therapy has been completed, cultures are negative, there is improvement in their condition, and improvement on chest x-ray. Because about 5% of patients have relapses, teach the patient to recognize the symptoms that occur with recurrent TB. If these symptoms occur, the patient should seek immediate medical attention. Teach the patient about factors that could reactivate TB, such as immunosuppressive therapy, cancer, and prolonged debilitating illness. If the patient has any of these, we must notify the HCP so that the patient can be monitored for TB reactivation. In some situations, it is necessary to put the patient on anti-TB therapy. Because smoking is associated with poor outcomes, encourage patients who smoke to quit. Provide patients with teaching and resources to help them stop smoking. Evaluation The expected outcomes are that the patient with TB will have: • Resolution of the disease • Normal lung function • Absence of any complications • No further transmission of TB 610 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Fungal Lung Infections BOX 30.4 EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE Adherence to TB Treatment Program TABLE 30.15 You are a nurse working in an outpatient health clinic with C.J., a 42-year-old woman diagnosed 2 months ago with active TB. She is on directly observed therapy (DOT). You notice C.J. has started to miss and has been late for her appointments. She tells you it is hard to make her appointments as a new job requires long work hours. She asks if she needs to continue with her visits to get her drugs. She says she is “feeling better” and does not understand what all the fuss over the drugs is about. She adds that she is “perfectly capable of taking my own pills.” Endemic Fungal Infections Blastomycosis Blastomyces dermatitidis Coccidioidomycosis Coccidioides immitis Histoplasmosis Histoplasma capsulatum Making Clinical Decisions Best Available Evidence Guidelines for effective case management of patients with TB include education, home visits, patient reminders, and incentives. TB clinic attendance and treatment completion rates are higher when patients take part in DOT compared to self-administered therapy. When appointments are missed, phone calls, Web-based videos, or home visits will engage patients, resulting in improved attendance and treatment completion. Clinician Expertise You are aware that patient-centered care includes being responsive to patients’ changing needs. You know that patients may stop attending appointments and taking their drugs when feeling well again. This can lead to treatment failure, the need to restart therapy, and multidrug resistance. Patient Preferences and Values C.J. tells you she has a busy job and does not always remember her appointments. She stated that she would like to be responsible for taking her drugs. Implications for Nursing Practice 1. What information you want to obtain from C.J.? 2. What teaching would you provide to C.J. about taking her own medications? 3. How will you determine if C.J. is adhering to the drug treatment plan? Source: Pradipta IS, Houtsma D, van Boven JFM, et al.: Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled studies, NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 30:21, 2020. ATYPICAL MYCOBACTERIA There are more than 30 acid-fast mycobacteria that cause diseases other than TB. These include lung disease, lymphadenitis, skin or soft tissue disease, and disseminated disease. Atypical mycobacteria are not airborne or transmitted by droplets. They can be found in tap water, soil, bird feces, and house dust. People who are immunosuppressed (e.g., HIV/AIDS) or have chronic lung disease are most susceptible to infection. Pulmonary symptoms include cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, fatigue, and blood-tinged sputum. Diagnosis is challenging and differs based on the site of the infection. We cannot tell this type of lung disease from TB either clinically or radiologically. Diagnostic studies done include a chest x-ray and 3 sputum specimens tested for AFB. Treatment may include a prolonged course of antibiotics, depending on the organism cultured and patient’s condition. PULMONARY FUNGAL INFECTIONS Pulmonary fungal pneumonia is an infectious process in the lungs caused by endemic (native and common) or Infection Organism Opportunistic Fungal Infections Aspergillosis Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus fumigatus Candidiasis Candida albicans Cryptococcosis Cryptococcus neoformans opportunistic fungi (Table 30.15). Endemic fungal pathogens cause infection in healthy people and immunocompromised people in certain areas. For example, Coccidioides, which causes coccidioidomycosis, is a fungus found in the soil of dry, low-rainfall areas.18 It is endemic in many areas of the southwestern United States. Opportunistic fungal infections occur in immunocompromised patients (e.g., those receiving chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs) and in patients with HIV and cystic fibrosis. Pulmonary fungal infections can be life-threatening. Pulmonary fungal infections are acquired by inhaling spores. They are not transmitted from person to person. The patient does not have to be placed in isolation. The manifestations are like those of bacterial pneumonia. Skin testing, serology, and biopsy methods help identify the infecting organism. The choice of antifungal agent is based on the pathogen identified on culture or most likely suspected. Amphotericin B is the standard therapy for treating serious systemic fungal infections. It must be given IV to achieve adequate blood and tissue levels because the GI tract does not absorb it well. Less serious infections can be treated with oral antifungals, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole (Diflucan), voriconazole (Vfend), and itraconazole (Sporanox). We monitor therapy effectiveness with fungal serology titers. LUNG ABSCESS Etiology and Pathophysiology A lung abscess is necrosis of lung tissue. It typically results from bacteria aspirated from the oral cavity in patients with periodontal disease. Lung abscess can also result from IV drug use, cancer, pulmonary emboli, TB, and various parasitic and fungal diseases. The abscess usually develops slowly, beginning with an enlarging area of infection that becomes necrotic and eventually forms a cavity filled with purulent material. Abscesses usually contain more than 1 type of microbe, most often anaerobic flora of the mouth and pharynx. The lung area most often affected due to aspiration is the posterior segment of the upper lobes. The abscess may erode into the bronchial system, causing foul-smelling or sour-tasting sputum. It may grow toward the pleura and cause pleuritic pain. Multiple small abscesses, sometimes referred to as necrotizing pneumonia, can occur within the lung. CHAPTER 30 Clinical Manifestations and Complications Manifestations usually occur slowly over a period of weeks to months, especially if anaerobic organisms are the cause. Symptoms of abscess caused by aerobic bacteria develop more acutely and resemble bacterial pneumonia. The most common is cough-producing purulent sputum (often dark brown) that is foul smelling and foul tasting. Hemoptysis is common, especially when an abscess ruptures into a bronchus. Other manifestations include fever, chills, weakness, night sweats, pleuritic pain, dyspnea, anorexia, and weight loss. Assessment reveals decreased breath sounds on auscultation over the involved segment of lung. Bronchial breath sounds may be transmitted to the periphery if the communicating bronchus becomes patent, and the segment begins to drain. Crackles may be present in the later stages as the abscess drains. The infection can spread through the bloodstream and cause several possible complications. Pulmonary abscess, bronchopleural fistula, bronchiectasis, and empyema from perforation of the abscess into the pleural cavity can occur.19 Diagnostic Studies A chest x-ray is often the only test needed to diagnose a lung abscess. The presence of a single cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level and local infiltrate confirms the diagnosis. CT scanning may be helpful if the abscess is not clear on chest x-ray. If there is drainage via the bronchus, sputum will contain the microorganisms that are present in the abscess. However, expectorated sputum samples are often contaminated with oral flora, making it hard to determine the responsible organism(s). Bronchoscopy may be used to (1) avoid oropharyngeal contamination, (2) collect a specimen if drainage is delayed, or (3) assess for underlying cancer. Pleural fluid and blood cultures may be used to identify the offending organisms. Although nonspecific, an elevated neutrophil count may indicate an infection. Necrotic pulmonary lesions also can be caused by lung infarction, pulmonary embolism, and sarcoidosis. Interprofessional and Nursing Care Monitor the patient’s vital signs, LOC, and respiratory rate and rhythm. Note any signs and symptoms of respiratory distress. Observe for any signs of hypoxemia. Apply O2 as needed. Teach the patient how to cough effectively. Chest physiotherapy and postural drainage are not recommended because they may promote movement of microorganisms into adjacent bronchi and other lobes of the lungs, extending infection. Rest, optimal nutrition, and adequate fluid intake promote recovery. If dentition is poor or dental hygiene is not adequate, encourage the patient to obtain dental care. Collaborate with the social worker to evaluate options for dental care if the patient has limited resources. IV antibiotic therapy should be started immediately. Clindamycin is first-line therapy for its effectiveness against Staphylococcus and anaerobic organisms. IV antibiotics are switched to oral antibiotics once the patient shows clinical and chest x-ray signs of improvement. Because of the need for prolonged antibiotic therapy, teach the patient to take antibiotics as directed for the entire Lower Respiratory Problems 611 prescribed period (see Table 15.9). Sometimes the patient must return periodically during the course of antibiotic therapy for repeat cultures and sensitivity tests to ensure that the infecting organism is not becoming resistant to the antibiotic. When antibiotic therapy is complete, the patient is re-evaluated. If the patient does not adequately respond to antibiotic treatment, percutaneous drainage of the abscess may be done. A small catheter, guided by CT or ultrasound, may be placed to drain the abscess. Surgery is sometimes done when reinfection of a large cavitary lesion occurs, when an empyema develops, or to establish a diagnosis when there is evidence of an underlying problem, such as cancer. The usual procedure in such cases is a lobectomy. A pneumonectomy may be needed for multiple abscesses. RESTRICTIVE RESPIRATORY DISORDERS Disorders that impair the ability of the chest wall and diaphragm to move with respiration are called restrictive respiratory disorders. There are 2 categories: extrapulmonary conditions, in which the lung tissue is normal, and intrapulmonary conditions, in which the primary cause is the lung or pleura. Examples of extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary conditions are listed in Table 30.16. The hallmark characteristic of a restrictive lung disorder is a reduced total lung capacity (TLC). The hallmark characteristic of an obstructive disorder is reduced forced expiratory volume (FEV1). Mixed obstructive and restrictive disorders sometimes occur together. For example, a patient may have both asthma Common Causes of Restrictive Lung Disease TABLE 30.16 Intrapulmonary Causes Parenchymal Disorders • Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) • Atelectasis • Chronic empyema • Interstitial lung diseases • Pneumonia Pleural Disorders • Pleural effusion • Pleurisy (pleuritis) • Pneumothorax Extrapulmonary Causes Central Nervous System • Head injury, central nervous system lesion (e.g., tumor, stroke) • Opioid and barbiturate overdose Chest Wall • Kyphoscoliosis • Obesity-hypoventilation syndrome Neuromuscular System • Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis • Guillain-Barré syndrome • Muscular dystrophy • Myasthenia gravis 612 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation (an obstructive problem) and pulmonary fibrosis (a restrictive problem). Pulmonary function tests are the best way to distinguish between restrictive and obstructive respiratory disorders. ATELECTASIS Atelectasis is a lung condition characterized by collapsed, airless alveoli. There may be decreased or absent breath sounds and dullness to percussion over the affected area. The most common cause is obstruction of the small airways with secretions. This is common in patients on bedrest and in almost all postoperative surgery patients. Normally, the pores of Kohn provide collateral passage of air from one alveolus to another. Deep inspiration opens the pores effectively. For this reason, deep-breathing exercises, coughing, incentive spirometry, and early mobility are important to prevent atelectasis and treat the patient at risk (see Chapter 20). PLEURISY Pleurisy (pleuritis) is an inflammation of the pleura. It can be caused by infectious diseases, cancer, autoimmune disorders, chest trauma, GI disease, and some drugs. The inflammation usually subsides once we treat the cause. The pain of pleurisy is typically abrupt, sharp in onset, and worse with inspiration. The patient’s breathing is short, shallow, and rapid to avoid unnecessary pleura and chest wall movement. A pleural friction rub may occur. This is the sound heard over areas where inflamed visceral pleura and parietal pleura rub together during inspiration. This sound, like a squeaking door, is usually loudest at peak inspiration. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause and providing pain relief. Teach the patient to splint the rib cage when coughing. If the pain is severe, intercostal nerve blocks may be considered. PLEURAL EFFUSION A pleural effusion is an abnormal collection of fluid in the pleural space. It is not a disease, but a sign of another condition. A balance among hydrostatic pressure, oncotic pressure, and capillary membrane permeability governs movement of fluid in and out of the pleural space. Fluid accumulation can be due to increased pulmonary capillary pressure, decreased oncotic pressure, increased pleural membrane permeability, or obstruction of lymphatic flow. Types of Pleural Effusions We classify pleural effusions as transudative or exudative depending on the protein content. A transudate effusion occurs mainly in non-inflammatory conditions. It is an accumulation of protein-poor, cell-poor fluid. The fluid is usually clear, pale yellow. Causes include (1) increased hydrostatic pressure found in HF or (2) decreased oncotic pressure from hypoalbuminemia (e.g., with chronic liver or renal disease). An exudative effusion results from increased capillary permeability due to an inflammatory reaction. The fluid is rich in protein. They most often occur with an infection or cancer (called a malignant effusion). An empyema is a collection of purulent fluid in the pleural space. Common causes include pneumonia, TB, lung abscess, and infected surgical chest wounds. Clinical Manifestations Common manifestations are dyspnea, cough, and occasional sharp, non-radiating chest pain that may be worse on inhalation. Breath sounds may be decreased over the affected area. A chest x-ray may show decreased chest movement on the affected side. A chest x-ray and CT reveal the volume and location of the effusion. Additional manifestations seen with empyema include fever, night sweats, cough, and weight loss. Interprofessional and Nursing Care The management of pleural effusions is to treat the underlying cause. For example, adequate treatment of HF with diuretics and sodium restriction may result in a decreased incidence of pleural effusion. The treatment of malignant effusions is more difficult. These effusions often re-occur and re-accumulate quickly after thoracentesis. Treatment options for an empyema include antibiotic therapy (to eradicate the causative organism), percutaneous drainage, chest tube insertion, and intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy (instilled through the chest tube to dissolve fibrous adhesions). Some patients may need surgery. Surgical options include drainage, decortication, or an open window thoracostomy. Chemical pleurodesis is done to obliterate the pleural space and prevent re-accumulation of effusion fluid. This procedure first requires chest tube drainage of the effusion. Once the fluid is drained, a chemical slurry is instilled into the pleural space. Talc is the most effective agent used. Other agents we use include doxycycline and bleomycin. The chest tube is clamped for 8 hours while the patient is turned in different positions. This allows the chemical to contact the entire pleural space. After 8 hours, the chest tube is unclamped and attached to a drainage unit. Chest tubes are left in place until fluid drainage is less than 150 mL/day and no air leaks are noted. Fever and chest pain are common side effects after pleurodesis. We provide supportive nursing care according to the patient’s needs. This may include O2 therapy to treat hypoxemia and analgesics to relieve chest pain. Implement measures to manage fever (see Table 12.5). Hydration, nutrition support, and positioning are part of the care plan. Work with the respiratory therapist to monitor the patient’s condition and provide chest physiotherapy. Care of the patient with a chest tube is described in Chapter 28. INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES Interstitial lung disease (ILD), or diffuse parenchymal lung disease, refers to more than 200 lung disorders in which the tissue between the air sacs of the lungs (the interstitium) is affected by inflammation or scarring (fibrosis).20 Most ILDs are rare. Many times, the cause of an ILD is unknown. Known causes are inhalation of occupational and environmental toxins, certain drugs, radiation therapy, connective tissue disorders, infection, and cancer. Treatment is aimed at reducing exposure to CHAPTER 30 the causative agent or treating the underlying disease process. While scarring is not reversible, treatment with corticosteroids and immunosuppressant drugs can minimize progression. A lung transplant may be an option for some patients. IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive disorder characterized by chronic inflammation and formation of scar tissue in the connective tissue.21 Risk factors include smoking and exposure to wood and metal dust. IPF affects more men. It typically first appears between the ages of 50 and 70 years. We do not know the cause of IPF. Manifestations include exertional dyspnea, a dry, nonproductive cough, clubbing of the fingers, and inspiratory crackles. Fatigue, weakness, anorexia, and weight loss may occur as the disease progresses. Chest x-ray findings are generally nonspecific. Pulmonary function tests may be abnormal, with reduced vital capacity and impaired gas exchange. Open lung biopsy using video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) often helps to confirm the pathology. It is the gold standard for diagnosis. The course is variable, and the prognosis is poor. The median survival rate is 2.5 to 3.5 years after diagnosis. There is no known cure for IPF. Many people diagnosed with IPF are first treated with a corticosteroid, sometimes in combination with other drugs that suppress the immune system (e.g., methotrexate, cyclosporine). Kinase inhibitor drugs, which block multiple pathways that are involved with scarring, include nintedanib (Ofev) and pirfenidone (Esbriet). O2 therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation should be prescribed for all patients. A lung transplant may be an option for those who meet criteria. SARCOIDOSIS Sarcoidosis is a chronic, multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown cause that mainly affects the lungs. The disease may also involve the skin, eyes, liver, kidney, heart, and lymph nodes. Signs and symptoms vary depending on what organs are affected. Pulmonary symptoms include dyspnea, cough, and chest pain. Many patients do not have symptoms. Staging and treatment decisions are based on chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests, and severity of symptoms. Some patients have a spontaneous remission. Treatment is aimed at suppressing the inflammatory response. Patients are followed every 3 to 6 months with pulmonary function tests, chest x-ray, and CT scan to monitor disease progression. CHEST TRAUMA AND THORACIC INJURIES Traumatic injuries to the chest contribute to many deaths. Chest injuries range from simple rib fractures to cardiorespiratory arrest. We classify the primary mechanisms of injury as either blunt trauma or penetrating trauma. Blunt trauma occurs when the chest strikes or is struck by an object. The impact can cause shearing and compression of chest structures. The external injury may appear minor, but Lower Respiratory Problems 613 internally, organs may be severely damaged. Rib and sternal fractures can easily tear lung tissue. In a high-velocity impact, shearing forces can result in tearing of the aorta. Compression of the chest may result in heart or lung contusion, crush injury, and organ rupture. In penetrating trauma, a foreign object impales or passes through the body tissues, creating an open wound. Examples include knife wounds, gunshot wounds, and injuries with other sharp objects. Emergency care of the patient with a chest injury is outlined in Table 30.17. The most common chest emergencies and their management are described in Table 30.18. FRACTURED RIBS Rib fractures are the most common type of chest injury from blunt trauma. Ribs 5 through 9 are most often fractured because they are the least protected by chest muscles. A splintered or displaced fractured rib can damage the pleura, lungs, heart, and other internal organs. Manifestations include pain at the site of injury, especially during inspiration and with coughing. The patient splints the affected area. They take shallow breaths to try to decrease the discomfort. Atelectasis and pneumonia may develop because of pain, decreased chest wall movement, and retained secretions. The goal of treatment is to decrease pain so that the patient can breathe adequately and clear secretions. Strapping the chest with tape or using a thoracic binder is not recommended. These limit chest expansion and predispose the person to atelectasis and hypoxemia. NSAIDs, opioids, and thoracic nerve blocks can be used to reduce pain and assist with deep breathing and coughing. Surgical plating of fractured ribs may be done for those patients with extreme chest wall deformity. Teaching should emphasize deep breathing, coughing, incentive spirometry, appropriate use of pain medications, and when appropriate, early mobility. FLAIL CHEST Flail chest results from the fracture of 3 or more consecutive ribs, in 2 or more separate places, causing an unstable segment (Fig. 30.4). It also can be caused by fracture of the sternum and several consecutive ribs. The resulting chest wall instability causes paradoxical movement during breathing. During inspiration, the affected part is sucked in, and during expiration, it bulges out. In other words, the affected (flail) area moves in the opposite direction with respect to the intact part of the chest. This paradoxical chest movement may prevent adequate ventilation and increase the work of breathing. A flail chest is usually apparent on assessment. The patient has rapid, shallow respirations and tachycardia. Movement of the thorax is asymmetric and uncoordinated. The patient may ventilate poorly and try to splint the chest to assist with breathing. Abnormal chest cavity movement, crepitus near the rib fractures, and chest x-ray all assist in the diagnosis. Initial therapy consists of ensuring adequate ventilation and supplemental O2 therapy. The goal is to promote lung expansion and ensure adequate oxygenation. The underlying injured TABLE 30.17 EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT Chest Trauma Etiology Assessment Findings Interventions Blunt •Assault with blunt object •Crush injury •Explosion •Fall •Motor vehicle collision •Pedestrian accident •Sports injury Respiratory •Audible air escaping from chest wound •↓ Breath sounds on side of injury •Cough with or without hemoptysis •Cyanosis of mouth, face, nail beds, mucous membranes •Dyspnea, respiratory distress •Frothy secretions •↓ O2 saturation •Tracheal deviation Initial •If unresponsive, immediately assess circulation, airway, and breathing. •If responsive, monitor airway, breathing, and circulation. •Apply high-flow O2 to keep SpO2 >90%. •Establish IV access with 2 large-bore catheters. Begin IV fluid resuscitation as appropriate. •Remove clothing to assess injury. •Cover sucking chest wound with nonporous dressing taped on 3 sides (vent dressing). •Stabilize impaled objects with bulky dressings. Do not remove object. •Assess for life-threatening injuries and treat appropriately. •Place patient in a semi-Fowler’s position if breathing is easier after cervical spine injury has been ruled out. •Give small amounts of analgesia as needed for pain and to help with breathing. •Prepare for emergency needle decompression if tension pneumothorax or cardiac tamponade present. Penetrating •Arrow •Gunshot •Knife •Stick Cardiovascular •Asymmetric BP values in arms •↓ BP •Chest pain •Distended neck veins •Dysrhythmias •Muffled heart sounds •Narrowed pulse pressure •Rapid, thready pulse Surface Findings •Abrasions •Asymmetric chest movement •Bruising •Contusions •Lacerations •Open chest wound •Subcutaneous emphysema TABLE 30.18 Ongoing Monitoring •Monitor LOC, vital signs, O2 saturation, cardiac rhythm, respiratory rate and rhythm, urine output. •Anticipate intubation for respiratory distress. •Release vent dressing if tension pneumothorax develops after sucking chest wound is covered. EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT Chest Injuries Injury and Description Manifestations Intervention Cardiac Tamponade Blood rapidly collects in pericardial sac, compresses myocardium because pericardium does not stretch, and prevents ventricles from filling. Muffled, distant heart sounds, hypotension, neck vein distention, ↑ central venous pressure Medical emergency. Pericardiocentesis with surgical repair as appropriate. Paradoxical movement of chest wall, respiratory distress. May be associated hemothorax, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion O2 as needed to maintain O2 saturation, analgesia. Positive pressure mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress; will also help stabilize flail segment. Treat associated injuries. Possible surgical fixation for severe damage to chest wall. Dyspnea, decreased or absent breath sounds, dullness to percussion, ↓ Hgb, shock (depending on blood volume lost) Chest tube insertion with chest drainage system. Autotransfusion of collected blood, treatment of hypovolemia as needed with IV fluid, packed red blood cells. Dyspnea, ↓ movement of involved chest wall, decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side, hyperresonance to percussion Chest tube insertion with chest drainage system. Cyanosis, air hunger, extreme agitation, subcutaneous emphysema, neck vein distention, hyperresonance to percussion, tracheal deviation away from affected side (late sign) Medical emergency: needle decompression followed by chest tube insertion with chest drainage system. Flail Chest Fracture of 2 or more adjacent ribs in 2 or more places with loss of chest wall stability (see Fig. 30.4). Hemothorax Blood in the pleural space, may or may not occur in conjunction with pneumothorax. Pneumothorax Air in pleural space (see Fig. 30.5). Tension Pneumothorax Air in pleural space that does not escape. Increased air in the pleural space shifts organs and increases intrathoracic pressure (see Fig. 30.6). CHAPTER 30 Lower Respiratory Problems 615 Collapsed lung Air Inspiration Fig. 30.5 Open pneumothorax. Collapse of lung results from disruption of chest wall and outside air entering the thoracic cavity. respiratory distress may be present, including short, shallow, rapid respirations, dyspnea, and low O2 saturation. On auscultation, breath sounds are absent over the affected area. A chest x-ray will show air or fluid in the pleural space and reduced lung volume. Types of Pneumothoraxes Expiration Fig. 30.4 Flail chest causes paradoxical respiration. On inspiration, the flail section moves inward with mediastinal shift to the uninjured side. On expiration, the flail section bulges outward with mediastinal shift to the injured side. lung may be contused, worsening hypoxemia. Analgesia can help promote adequate respiration. Some patients may need mechanical ventilation. In cases of extreme deformity, surgical fixation of the flail segment may be done. The lung parenchyma and fractured ribs heal with time. Some patients continue to have intercostal pain several weeks after the flail chest has resolved. PNEUMOTHORAX A pneumothorax is caused by air entering the pleural cavity. Normally, negative (subatmospheric) pressure exists between the visceral pleura (surrounding the lung) and parietal pleura (lining the chest cavity), known as the pleural space. The pleural space has a few milliliters of lubricating fluid to reduce friction when the tissues move. When the volume of air that enters this normally subatmospheric space increases, lung volume decreases. As a result, the change to positive pressure causes a partial or complete lung collapse. We can describe a pneumothorax as open (air entering through an opening in the chest wall) or closed (no external wound). Penetrating trauma allows air to enter the pleural space through an opening in the chest wall (Fig. 30.5). A penetrating chest wound may be called a sucking chest wound, since air enters the pleural space through the chest wall during inspiration. A pneumothorax should be suspected after any trauma to the chest wall. If a pneumothorax is small, mild tachycardia and dyspnea may be the only manifestations. With a larger pneumothorax, Spontaneous Pneumothorax A spontaneous pneumothorax typically occurs due to the rupture of small blebs (air-filled sacs) on the surface of the lung. These blebs can occur in healthy, young people or from lung disease, such as COPD, asthma, cystic fibrosis, and pneumonia. Smoking increases the risk for bleb formation. Other risk factors include being tall and thin, male gender, family history, and previous spontaneous pneumothorax. Iatrogenic Pneumothorax Iatrogenic pneumothorax can occur due to laceration or puncture of the lung during medical procedures. For example, transthoracic needle aspiration, subclavian catheter insertion, pleural biopsy, and transbronchial lung biopsy all have the potential to injure the lung. Barotrauma from excessive ventilatory pressure during manual or mechanical ventilation can rupture alveoli, creating a pneumothorax. Esophageal procedures may result in a pneumothorax. For example, tearing of the esophageal wall during insertion of a gastric tube can allow air from the esophagus to enter the mediastinum and pleural space. Tension Pneumothorax Tension pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space but cannot escape. The continued accumulation of air in the pleural space causes increasingly elevated intrapleural pressures. This results in compression of the lung on the affected side and pressure on the heart and great vessels, pushing them away from the affected side (Fig. 30.6). The mediastinum shifts toward the unaffected side, compressing the “good” lung, which further compromises oxygenation and ventilation. As the pressure increases, venous return decreases and cardiac output falls. Tension pneumothorax may result from either an open or a closed pneumothorax. In an open chest wound, a flap may act as a one-way valve. Thus, air can enter on inspiration but cannot escape. Tension pneumothorax can occur with mechanical ventilation and resuscitative efforts. It can also occur if chest tubes are clamped or become blocked in a patient with a 616 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Midline Superior vena cava TABLE 30.19 Tracheal deviation Inferior vena cava Pneumothorax Mediastinal shift Fig. 30.6 Tension pneumothorax. As pleural pressure on the affected side increases, mediastinal displacement occurs, causing respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Tracheal deviation is an external (but late) sign of mediastinal shift. pneumothorax. Unclamping the tube or relieving the obstruction may correct this situation. Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency. It affects both the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Manifestations include severe dyspnea, marked tachycardia, neck vein distention, and profuse diaphoresis. Decreased or absent breath sounds will be present on the affected side. Tracheal deviation is a very late sign. If the problem is not quickly identified and tension in the pleural space is not relieved (needle compression), the patient is likely to die from inadequate cardiac output and severe hypoxemia. Hemothorax Hemothorax is an accumulation of blood in the pleural space from injury to the chest wall, diaphragm, lung, blood vessels, or mediastinum. When it occurs with pneumothorax, it is called a hemopneumothorax. The patient with a traumatic hemothorax needs immediate insertion of a chest tube for evacuation of the blood. Sometimes, blood drained from a chest tube can be reinfused back into the patient (autotransfusion) after the injury. However, this requires special equipment and set-up prior to chest tube insertion. Chylothorax Chylothorax is the presence of lymphatic fluid in the pleural space. The thoracic duct is disrupted either traumatically or from cancer, allowing lymphatic fluid to fill the pleural space. This milky white fluid is high in lipids. Normal lymphatic flow through the thoracic duct is 1500 to 2500 mL/day. This amount can increase up to 10-fold after ingesting fats. Some cases heal with conservative treatment (chest drainage, bowel rest, diet). Octreotide may reduce the flow of lymphatic fluid. Surgery (thoracic duct ligation) and pleurodesis (the artificial production of adhesions between the parietal and visceral pleura) are options for some persons. Interprofessional Care Treatment of a pneumothorax depends on its severity, underlying cause, and hemodynamic stability of the patient. If the Causes of Pulmonary Edema • Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) • Altered capillary permeability of lungs: aspiration, inhaled toxins, inflammation (e.g., pneumonia), severe hypoxia, near-drowning • Anaphylactic (allergic) reaction • Hypoalbuminemia: nephrotic syndrome, liver disease, nutritional disorders • Left ventricular (heart) failure • Lymph system cancer (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma) • Overhydration with IV fluids • O2 toxicity • Unknown causes: neurogenic condition, opioid overdose, reexpansion pulmonary edema, high altitude patient is stable and has minimal air and/or fluid accumulated in the intrapleural space, no treatment may be needed since the condition may resolve spontaneously. Pre-hospital emergency care consists of covering the wound with an occlusive dressing that is secured on 3 sides (vent dressing). During inspiration, as negative pressure is created in the chest, the dressing pulls against the wound, preventing air from entering the pleural space. During expiration, as the pressure rises in the pleural space, the dressing is pushed out and air escapes through the wound and from under the dressing. If the object that caused the open chest wound is still in place, pre-hospital care providers will not remove it. They will stabilize the impaled object with a bulky dressing and arrange transport to the nearest medical facility. In acute care, the most definitive and common treatment of pneumothorax and hemothorax is to insert a chest tube and connect it to water-seal drainage. Repeated spontaneous pneumothorax may need surgical treatment with a partial pleurectomy, stapling, or pleurodesis to promote adherence of the pleurae to one another. Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency, requiring urgent needle decompression followed by chest tube insertion to water-seal drainage. Care of the patient with chest tubes is described in Chapter 28. VASCULAR LUNG DISORDERS PULMONARY EDEMA Pulmonary edema is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the alveoli and interstitial spaces of the lungs. It is a complication of various heart and lung problems (Table 30.19). In severe cases, pulmonary edema can be a life-threatening medical emergency. The most common cause of pulmonary edema is left-sided HF. The patient often presents with varying degrees of dyspnea, diaphoresis, and wheezing, depending upon the severity of pulmonary edema and underlying medical condition. A 3rd heart sound may be present. Sputum may be blood-tinged and frothy sputum. A chest x-ray is the best option for confirming the diagnosis. Treatment is often directed towards finding the underlying cause of the edema and reducing the amount of fluid in the lungs. Goals include simultaneously improving oxygenation, ventilation, and cardiac output. CHAPTER 30 Place the patient in a semi or high Fowler’s position. Administer O2 to keep SpO2 greater than 90%. This may require low or high flow O2 delivery devices, non-invasive ventilation (e.g., Bi-PAP), or mechanical ventilation. Preload reduction may be accomplished by giving IV diuretics (e.g., furosemide) or nitroglycerine. Small amounts of IV morphine can reduce afterload. Cardiac output can be supported with IV Dobutamine. Monitor the patient’s vital signs, work of breathing, breath sounds, urinary output, electrolyte balance, and response to treatment. PULMONARY EMBOLISM Etiology and Pathophysiology Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the blockage of 1 or more pulmonary arteries by a thrombus, fat or air embolus, or tumor tissue. A PE consists of material that gains access to the venous system and then to the pulmonary circulation. The PE travels with blood flow through ever-smaller blood vessels until it lodges and obstructs perfusion of the alveoli. The lower lobes are most often affected. Most PEs arise from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the deep veins of the legs. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the preferred term to describe the spectrum from DVT to PE. Other sites of origin of PE include femoral or iliac veins, right side of the heart (atrial fibrillation), and pelvic veins (especially after surgery or childbirth). Upper extremity DVT sometimes occurs in the presence of central venous catheters or arterial lines. These cases may resolve with removal of the catheter. A saddle embolus refers to a large thrombus lodged at an arterial bifurcation (Fig. 30.7). Less common causes include fat emboli (from fractured long bones), air emboli (from improperly administered IV therapy), bacterial vegetation on heart valves, amniotic fluid, and cancer.22 Risk factors for PE include immobility or reduced mobility, surgery within the last 3 months (especially pelvic and lower extremity surgery), history of VTE, cancer, obesity, Lower Respiratory Problems 617 oral contraceptives, hormone therapy, smoking, prolonged air travel, HF, pregnancy, and clotting disorders. Clinical Manifestations The signs and symptoms of PE are varied and nonspecific, making diagnosis difficult. Manifestations depend on the type, size, and extent of emboli. Small emboli may go undetected or cause vague, transient symptoms. Symptoms may begin slowly or appear suddenly. Dyspnea is the most common presenting symptom in patients with PE. Mild to moderate hypoxemia may occur. Other manifestations include tachypnea, cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, crackles, wheezing, fever, accentuation of pulmonic heart sound, tachycardia, and syncope. Massive PE may cause a sudden change in mental status, hypotension, feelings of impending doom, and cardiorespiratory arrest. Complications About 10% of patients with massive PE die within the 1st hour. Identifying the patient “at-risk” for VTE is essential. Treatment with anticoagulants significantly reduces mortality. Complications include pulmonary infarction and pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary infarction (death of lung tissue) is most likely when there is (1) occlusion of a large or medium-sized pulmonary vessel (more than 2 mm in diameter), (2) insufficient collateral blood flow from the bronchial circulation, or (3) pre-existing lung disease. Infarction results in alveolar necrosis and hemorrhage. Sometimes the necrotic tissue becomes infected, and an abscess may develop. Pleural effusions are common. Pulmonary hypertension results from hypoxemia or from involvement of a large surface area of the pulmonary bed. As a single event, a PE rarely causes pulmonary hypertension. Recurrent PEs or PEs that do not completely resolve gradually reduce capillary bed blood flow over time. This may eventually cause chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.23 Dilation and hypertrophy of the right ventricle occurs. Depending on the severity of pulmonary hypertension and how Large coiled central clot extending into and obstructing both pulmonary arteries Peripheral emboli (multiple small formed clot fragments in peripheral arteries) Pulmonary trunk Fig. 30.7 Saddle pulmonary embolus. This embolus straddles the bifurcation of a major artery, with the clot extending down into both right and left branches of the major vessel. 618 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation quickly it develops, outcomes can vary. Some patients dying within months while and others live for decades. TABLE 30.20 Interprofessional Care Acute Pulmonary Embolism Diagnostic Studies Diagnostic Assessment • History and physical assessment • Chest x-ray • Continuous ECG monitoring • Pulse oximetry, ABGs • Spiral (helical) CT scan (gold standard for ventilated or non-ventilated patient); if unavailable, computed tomography angiography (CTA) or pulmonary angiography • Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) lung scan (best for non-ventilated patient) • Potentially useful lab tests (but not diagnostic); D-dimer level, troponin level, b-natriuretic peptide level • Ultrasound of upper or lower extremities (based on likely source) ABG analysis is important but does not diagnose a PE. The PaO2 may be low because of inadequate oxygenation from occluded pulmonary vessels preventing matching of perfusion to ventilation. The pH is often normal unless respiratory alkalosis develops because of prolonged hyperventilation or to compensate for lactic acidosis caused by shock. Abnormal findings may be seen on a chest x-ray (atelectasis, pleural effusion) and ECG (nonspecific ST segment and T wave changes), but they are not diagnostic for PE. Serum troponin levels and b-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels are often high. D-dimer is a laboratory test that measures the amount of cross-linked fibrin fragments. These fragments are the result of clot degradation. The disadvantage of D-dimer testing is that it is neither specific (many other conditions cause increases) nor sensitive, because up to 50% of patients with a small PE have normal results. Patients with suspected PE and an elevated D-dimer level but normal venous ultrasound may need a spiral CT or lung scan. A spiral (helical) CT scan (CT angiography or CTA) is the most common test to diagnose PE. An IV injection of contrast media is needed to view the pulmonary blood vessels. The scanner continuously rotates around the patient while obtaining views (slices) of the pulmonary vasculature. This allows us to see all anatomic regions of the lungs. Computer reconstruction gives a 3-D picture and assists in seeing PEs. If a patient cannot have contrast media, a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan is done. The V/Q scan has 2 parts. It is most accurate when both are done: 1.Perfusion scanning involves IV injection of a radioisotope. A scanning device images the pulmonary circulation. 2.Ventilation scanning involves inhalation of a radioactive gas, such as xenon. Scanning reflects the distribution of gas through the lung. The ventilation portion requires the patient’s cooperation. It may not be possible to perform in the critically ill patient, especially if the patient is intubated. Interprofessional Care To reduce mortality, we start treatment as soon as we suspect a PE (Table 30.20). The goals are to (1) facilitate optimal cardiorespiratory function, (2) ensure adequate blood flow, (3) prevent further growth or extension of thrombi, and (4) prevent and avoid further recurrence and any complications. Immediate assessment should focus on cardiorespiratory status, which varies by the size and location of the PE. O2 should be given by mask or cannula when hypoxemia is present. The FIO2 is titrated based on ABG analysis. In some situations, mechanical ventilation is needed to maintain adequate oxygenation. Respiratory measures—including turning, coughing, deep breathing, and incentive spirometry—are important to help prevent atelectasis. Pain from pleural irritation or reduced coronary blood flow is treated with opioids. If HF is present, diuretics are used. If manifestations of shock are present, IV fluids and vasopressor agents are given as needed to support circulation. Management • Supplemental O2, intubation if needed • Monitor hemoglobin, assess patient for bleeding • Monitor activated partial thromboplastin time and international normalized ratio levels • Balance activity and rest • Inferior vena cava filter • Pulmonary embolectomy in life-threatening situation Drug Therapy • Unfractionated heparin IV • Low-molecular-weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin [Lovenox]) • Factor Xa Inhibitors (e.g., apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban) • Thrombin Inhibitors (e.g., dabigatran [Pradaxa]) • Warfarin (Coumadin) for long-term therapy • Fibrinolytics (e.g., activase) for life-threatening situation • Analgesia Drug Therapy Immediate anticoagulation is required for patients with PE. Drug therapy for patients with acute PE occurs in 3 phases: initial (for the first 7 days), longer (up to 6 weeks), and extended (6 months and beyond). Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (e.g., enoxaparin, fragmin, fondaparinux) is the recommended treatment for patients with acute PE. LMWH is safer and more effective than unfractionated heparin. Monitoring the aPTT is not necessary or useful with LMWH. Unfractionated IV heparin is effective but hard to titrate to therapeutic levels. Warfarin (Coumadin), an oral anticoagulant, should be started at the time of diagnosis. Warfarin should be given for at least 3 to 6 months and then reevaluated. Alternatives to warfarin include apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), and edoxaban (Savaysa). Anticoagulant therapy may be contraindicated if the patient has complicating factors, such as liver problems (causing changes in the clotting), overt bleeding, a history of hemorrhagic stroke, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), or other blood dyscrasias. Some HCPs use direct thrombin inhibitors (see Table 41.10) in the treatment of PE. Similarly, fibrinolytic agents, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or alteplase (Activase), may help dissolve the PE and the source of the thrombus in the pelvis or deep leg veins, thus, decreasing the risk for recurrent emboli. Fibrinolytic therapy is discussed in Chapter 37. CHAPTER 30 Pulmonary embolism IVC filter with hook Blood clot caught in IVC filter Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) Fig. 30.8 Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter. This small device is placed in the inferior vena cava. It helps trap blood clots that may travel from the lower extremities up towards the brain and heart. Lower Respiratory Problems 619 Initially, keep the patient on bed rest in a semi-Fowler’s position to facilitate breathing. Assess cardiopulmonary status with careful monitoring of vital signs, cardiac rhythm, pulse oximetry, ABGs, and lung sounds. Apply O2 therapy as directed. Maintain a patent IV line for medications and fluid therapy. Monitor laboratory results to ensure therapeutic ranges of INR (for warfarin) and aPTT (for IV heparin). Monitor platelet counts for thrombocytopenia and the development of HIT. Observe the patient for complications of anticoagulant and fibrinolytic therapy (e.g., bleeding, bruising). Implement fall precautions once the patient can be out of bed. The patient may be anxious because of pain, inability to breathe, and fear of death. Provide emotional support and reassurance to help relieve the patient’s anxiety. Teaching about long-term anticoagulant therapy is essential. Anticoagulant therapy continues for at least 3 months. Patients with large or recurrent emboli may be treated indefinitely with anticoagulants. INR levels are drawn at intervals and warfarin dosage is adjusted. Some patients are monitored by nurses in an anticoagulation clinic. Long-term management of PE is similar to that for the patient with VTE (see more about VTE in Chapter 41). Discharge planning is aimed at preventing worsening of the current condition and avoiding complications and recurrence. Reinforce the need for the patient to return to the HCP for regular follow-up care. PULMONARY HYPERTENSION Surgical Therapy Hemodynamically unstable patients with massive PE in whom thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated may be candidates for pulmonary embolectomy. Embolectomy, the removal of emboli, can be achieved through a diagnostic imaging (vascular catheter) or surgical approach. It can help decrease right ventricular afterload. Surgical outcomes have improved in recent years, in part due to rapid diagnosis and enhanced surgical procedures. Percutaneous interventional techniques, surgical embolectomy, ultrasound-guided catheter thrombolysis, and aspiration thrombectomy are newer, moderately invasive procedures for PE. In patients who are at high risk and for whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter may be the treatment of choice (Fig. 30.8). This device, inserted through the femoral vein, is placed at the level of the renal veins in the inferior vena cava. Once inserted, the filter expands and prevents the movement of large clots upwards and into the pulmonary system. Complications are rare but include misplacement, migration, and perforation. In pulmonary hypertension there is an elevated pulmonary artery pressure (greater than 20 mm Hg) from an increase in resistance to blood flow through the pulmonary circulation. Normally, the pulmonary circulation is characterized by low resistance and low-pressure vessels. In pulmonary hypertension, the pulmonary pressures are high. There are 5 classes of pulmonary hypertension.24 Each class (group) is based on cause: Group 1: Attributed to medication, specific diseases, genetic (inherited) link, or idiopathic Group 2: Related to left-sided HF Group 3: Related to the lungs and hypoxia Group 4: Related to the cardiovascular system and thromboembolism Group 5: Multifactorial (and often unclear) origins (e.g., hematologic, metabolic, renal involvement) Pulmonary hypertension can occur as a primary disease (idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension) or as a secondary complication of a respiratory, heart, autoimmune, liver, or connective tissue problem (secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension). NURSING MANAGEMENT: PULMONARY EMBOLISM IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION Prevention of PE begins with prevention of DVT. Identifying the “at risk” patient is essential. Nursing measures aimed at prevention of PE are similar to those for prophylaxis of VTE. These include the use of intermittent pneumatic compression devices, early ambulation, and anticoagulant medications. Etiology and Pathophysiology Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) was previously known as primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH). The cause of IPAH is unknown. It is related to connective tissue diseases, cirrhosis, and HIV. The exact relationship between these 620 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation PATHOPHYSIOLOGY MAP Insult occurs (hormonal, mechanical, other) Pulmonary endothelial injury • Smooth muscle proliferation • Vascular scarring Sustained pulmonary hypertension Right ventricular hypertrophy Cor pulmonale Right-sided heart failure Although IPAH has no cure, treatment can relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and prolong life. If untreated, IPAH can rapidly progress, causing right-sided HF and death within a few years. New drug therapy has greatly improved survival. Drug therapy consists of agents that dilate the pulmonary blood vessels, reduce right ventricular overload, and reverse remodeling (Table 30.21). Diuretics are used to manage peripheral edema. Anticoagulants reduce the risk of thrombus formation. Because hypoxia is a potent pulmonary vasoconstrictor, low-flow O2 gives symptomatic relief. The goal is to keep O2 saturation 90% or greater. Surgical therapy includes pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), in which clots are removed from the pulmonary arteries. It is a technically demanding, high risk procedure, done only at certain centers. Atrial septostomy (AS) is a palliative procedure that involves the creation of an intra-atrial right-to-left shunt to decompress the right ventricle. It is used for some patients awaiting a lung transplant. A lung transplant is an option for patients who do not respond to drug therapy and progress to severe right-sided HF. Disease recurrence has not been reported in persons who had a lung transplant. Fig. 30.9 Pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale. disorders and IPAH is unclear. Similarly, the pathophysiology of IPAH is poorly understood. We believe that some type of insult (e.g., hormonal, mechanical) to the pulmonary endothelium may occur, causing a cascade of events leading to vascular scarring, endothelial dysfunction, and smooth muscle proliferation (Fig. 30.9). IPAH affects more females. Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Studies The classic symptoms are dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. Exertional chest pain, dizziness, and syncope may occur. These are related to the inability of cardiac output to increase in response to increased O2 demand. Abnormal heart sounds may be heard, including an S3. Eventually, as the disease progresses, dyspnea occurs at rest. Pulmonary hypertension increases the workload of the right ventricle and causes right ventricular hypertrophy (a condition called cor pulmonale) and, eventually, HF. Right-sided cardiac catheterization is the definitive test to diagnose any type of pulmonary hypertension. It gives an accurate measurement of pulmonary artery pressures, cardiac output, and pulmonary vascular resistance. Diagnostic evaluation often includes ECG, chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests, echocardiogram, and CT scan. Confirmation of IPAH requires a workup to exclude conditions that may cause secondary pulmonary hypertension. The mean time between onset of symptoms and the diagnosis is about 2 years. By the time patients become symptomatic, the disease is already in the advanced stages and the pulmonary artery pressure is 2 to 3 times normal values. Interprofessional and Nursing Care Early recognition is essential to interrupt the vicious cycle responsible for disease progression. Encourage patients to report unexplained shortness of breath, syncope, chest discomfort, and feet and ankle edema to their HCP. SECONDARY PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION Secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension (SPAH) occurs when another disease causes a chronic increase in pulmonary artery pressures. The primary disease can cause anatomic or vascular changes that result in the pulmonary hypertension. SPAH can develop due to parenchymal lung disease, left ventricular dysfunction, intracardiac shunts, chronic PE, or systemic connective tissue disease.25 The symptoms can reflect the underlying disease, but some are directly related to SPAH. These include dyspnea, fatigue, lethargy, and chest pain. Initial physical findings can include right ventricular hypertrophy and signs of right-sided HF (increased pulmonic heart sound, S4 heart sound, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly). Diagnosis of SPAH is like that of IPAH. With SPAH, we treat the underlying primary disorder. When irreversible pulmonary vascular damage has occurred, therapies for IPAH are started. A PTE may offer a cure for patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension caused by PE. COR PULMONALE Cor pulmonale is enlargement of the right ventricle caused by a primary respiratory disorder. Almost any disorder that affects the respiratory system can cause cor pulmonale. The most common cause is COPD. Pulmonary hypertension is usually a pre-existing condition in the person with cor pulmonale. Overt HF may be present. Fig. 30.9 outlines the cause and pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale. Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Studies Manifestations are subtle and often masked by symptoms of the lung problem. Common symptoms include exertional dyspnea, CHAPTER 30 Lower Respiratory Problems 621 TABLE 30.21 Drug Therapy Pulmonary Hypertension Drug Mechanism of Action Calcium Channel Blockers diltiazem (Cardizem, cardizem •↓ BP LA) •Act on vascular smooth muscle, causing dilation nifedipine (Procardia) •Lower pulmonary artery pressure Endothelin Receptor Antagonists ambrisentan (Letairis) •Binds to endothelin-1 receptors and blocks bosentan (Tracleer) the constriction of pulmonary arteries macitentan (Opsumit) •Promotes relaxation of pulmonary arteries •↓ Pulmonary artery pressure Phosphodiesterase (Type 5) Enzyme Inhibitors sildenafil (Revatio) •Promote smooth muscle relaxation in lung tadalafil (Adcirca) vasculature Vasodilators iloprost (Ventavis) treprostinil (Tyvaso) Vasodilators epoprostenol (Flolan, Veletri) treprostinil (Remodulin) Considerations •Successful in a very small number of patients •Only used in patients who do not have right-sided HF •Used at high doses in comparison to other uses of calcium channel blockers •Given orally •For patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to IV symptoms •Hepatotoxic •Monitor liver function tests monthly •Given orally •Contraindicated in patients taking nitroglycerin, since may cause refractory hypotension •Synthetic analogs of prostacyclin (PGI2) •Dilate systemic and pulmonary arterial vasculature •Help relieve dyspnea •Given by inhalation •For patients with NYHA class III or IV HF •Given 6–9 times a day using a disk inserted into a nebulizer •Can cause orthostatic hypotension. Do not give to patients with systolic BP <85 mm Hg. •Promote pulmonary vasodilation and reduce pulmonary vascular resistance •Relieves dyspnea and chest congestion •For patients who do not respond to calcium channel blockers or have NYHA class III or IV right-sided HF •Given by continuous IV (central line) or continuous subcutaneous route •Half-life of epoprostenol is short. Potential clinical deterioration from abrupt withdrawal if infusion disrupted tachypnea, cough, and fatigue. Physical signs include evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy on ECG and an increase in intensity of S2. Chronic hypoxemia leads to polycythemia and increased total blood volume and viscosity. Polycythemia is often present in cor pulmonale from COPD. If HF accompanies cor pulmonale, peripheral edema, weight gain, distended neck veins, full, bounding pulse, and enlarged liver may occur. Various laboratory tests and imaging studies are used to confirm the diagnosis of cor pulmonale (Table 30.22). Interprofessional and Nursing Care Early identification is essential before changes to the heart occur that may be irreversible. Management is directed at determining the cause and treating the underlying problem. Long-term O2 therapy, the mainstay of treatment to correct the hypoxemia, reduces vasoconstriction and pulmonary hypertension. All other interventions are tailored for each patient. If fluid, electrolyte, and/or acid-base imbalances are present, they must be corrected. Diuretics may help decrease plasma volume and reduce the workload on the heart but must be used with caution. In some cases, decreases in fluid volume from diuresis can worsen heart function. Bronchodilator therapy is needed if the underlying respiratory problem is due to an obstructive disorder. Other treatments may include vasodilator therapy, calcium channel blockers, anticoagulants, digitalis, and phlebotomy. All have varying degrees of success. Chronic management of cor pulmonale from COPD is like that described for COPD (see Chapter 31). ENVIRONMENTAL LUNG DISEASES Environmental or occupational lung diseases result from inhaled dust or chemicals. The extent of lung damage is influenced by the toxicity of the inhaled substance, amount and duration of exposure, and individual susceptibility. Environmentally induced lung disease includes pneumoconiosis, chemical pneumonitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Pneumoconiosis is a general term for a group of lung diseases caused by inhalation and retention of mineral or metal dust particles. The literal meaning of pneumoconiosis is “dust in the lungs.” We classify these diseases by the origin of the dust (e.g., silicosis, asbestosis, berylliosis). For example, silicosis occurs from inhaling silica from sand and rock. Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP), or black lung, is caused by inhaling large amounts of coal dust. It is a hazard for underground coal miners. The inhaled substance is ingested by macrophages, which releases substances that cause cell injury and death. 622 SECTION 6 TABLE 30.22 Cor Pulmonale Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Interprofessional Care Diagnostic Assessment • History and physical assessment • ABGs, SpO2 • Serum and urine electrolytes • b-Type natriuretic peptide (BNP) • ECG • Chest x-ray • Echocardiography • CT scan, MRI • Cardiac catheterization Management • Treat the cause (which may be difficult, often involves improving O2 delivery to the patient and right ventricular function) • O2 therapy • Low-sodium diet Drug Therapy (Depending on the Primary Cause) • Bronchodilators • Diuretics (use with caution) • Pulmonary vasodilators • Calcium channel blockers • Inotropic agents • Digitalis • Anticoagulation therapy Fibrosis occurs from tissue repair after inflammation. Breathing problems become evident after many years of repeated exposure, resulting in diffuse pulmonary fibrosis (excess connective tissue). Asbestos is a group of minerals composed of microscopic fibers. For many years, asbestos was used for insulation and to help fireproof buildings. When disturbed, asbestos releases tiny filament particles into the air. Once inhaled, the tiny fibers become deposited within the lung. Asbestosis causes chronic lung inflammation. People with repeated exposure are at a greater risk for disease. Lung cancer, either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, is the most frequent cancer from asbestos exposure. There is a lapse of at least 15 to 19 years between first exposure and development of lung cancer. Mesothelioma, both pleural and peritoneal, is associated with asbestos exposure.26 Chemical pneumonitis results from exposures to toxic chemical fumes. There are 2 types of chemical pneumonitis: acute and chronic. In the acute form, there is diffuse lung injury characterized by pulmonary edema. Chronically, the clinical picture is that of bronchiolitis obliterans (obstruction of the bronchioles due to inflammation and fibrosis). The chest x-ray is normal or shows hyperinflation. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a form of parenchymal lung disease seen when a person inhales an antigen to which they are allergic. There are acute, subacute, and chronic forms. Examples include bird fancier’s lung (exposure to particles in feathers and droppings of birds) and farmer’s lung (inhalation of hay dust particles). Clinical Manifestations Symptoms of many environmental lung diseases may not occur until at least 10 to 15 years after the initial exposure to the inhaled irritant. Manifestations common to all pneumoconiosis include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and weight loss. Pulmonary function studies often show reduced vital capacity. A chest x-ray often shows lung involvement specific to the primary problem. CT scans have been useful in detecting early lung involvement. COPD is the most common complication of environmental lung disease. Other associated problems include acute pulmonary edema, lung cancer, mesothelioma, and TB. Appearance of these symptoms and complications are often the reason the patient seeks medical care. Cor pulmonale is a late complication. It is more common in conditions where there is diffuse pulmonary fibrosis. Interprofessional and Nursing Care The best approach to managing environmental lung diseases is to prevent or decrease environmental and occupational exposure. Teach those at risk about the use of appropriate PPE. Wearing masks and ensuring well-designed, effective ventilation systems are in place are appropriate for some occupations. Smoke inhalation by nonsmokers has led to laws requiring a smoke-free workplace. Periodic inspections and monitoring of workplaces by agencies such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reinforce employers’ obligations to provide a safe work environment. NIOSH is responsible for workplace safety and health regulations in the United States. Encourage regular medical check-ups for those in high-risk occupations. Early diagnosis is essential to halting the disease process. Care is directed toward preventing disease progression and monitoring, improving, or controlling respiratory symptoms. Treatment depends on the cause and severity of the condition. Acute care may include O2 therapy, IV fluid, percussion therapy, inhaled bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and NSAIDs. Some patients need mechanical ventilation. Longer term care includes pulmonary rehabilitation. Patients should be immunized against pneumococcal pneumonia and influenza. Discontinuing exposure to the offending inhalant and smoking cessation may or may not be effective in stopping disease progression. LUNG TRANSPLANTATION Lung transplantation has become an important alternative option for patients with end-stage lung disease. Unfortunately, the limiting factor is the lack of donors. A variety of pulmonary problems are potentially treatable with a lung transplant (Table 30.23). Better patient selection criteria, improvements in surgical techniques, enhanced immunosuppression, and excellent postoperative care have resulted in improved survival rates. Preoperative Care Patients being considered for a lung transplant have an extensive evaluation. Absolute contraindications include cancer CHAPTER 30 TABLE 30.23 Lung Transplant Common Indications for a • Progressive lung disease and greater than 50% chance of death in the next 2 years without a lung transplant • Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) • Cystic fibrosis • Emphysema with α1-antitrypsin deficiency • Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis • Interstitial lung disease • Pulmonary arterial hypertension within the past 2 years (excluding some types of skin cancer), untreatable advanced dysfunction of another major organ system (e.g., heart, liver, renal failure), uncorrectable bleeding condition, mycobacterium tuberculosis, severe obesity (BMI >35kg/ m2), and significant psychosocial problems.27 The patient and family must be able to cope with complex postoperative care (e.g., adherence to immunosuppressive therapy, monitoring for infection). Many transplant centers require outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation before surgery to maximize physical conditioning. In the United States, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) designates recipients of donor lungs based on a lung allocation score (LAS). The LAS helps prioritize waiting list recipients based on the urgency of need and expected post-transplant survival expectations. Patients who are accepted as transplant candidates must always carry a pager in case a donor organ becomes available. They must be prepared to be at their transplant center at a moment’s notice. Patients may have to limit their travel in case they need to quickly return to the transplant center. Surgical Procedure Four types of lung transplant procedures are available: single-lung, bilateral lung, heart-lung, and transplantation of lobes from a living-related donor. A single-lung transplant involves a thoracotomy incision on the affected side of the chest. The opposite lung is ventilated while the diseased lung is excised, and the donor lung implanted. There are 3 anastomoses: bronchus, pulmonary artery, and pulmonary veins. In a bilateral lung transplant, the incision is made across the sternum and the donor lungs are implanted separately. A median sternotomy incision is used for a heartlung transplant procedure. Lobar transplantation from living donors is reserved for those who urgently need a transplant and are unlikely to survive until a donor becomes available. Most of these recipients are patients with cystic fibrosis. The donors are their parents or relatives. Once anastomosis is complete, the lung is gently reinflated, perfusion is re-established, chest tubes are inserted, and the surgical incision is closed. Postoperative Care Immediate postoperative care often includes mechanical ventilation and hemodynamic monitoring in the ICU. IV therapy, immunosuppression, nutrition support, detection of early rejection, and preventing or treating complications, including Lower Respiratory Problems 623 infection, are priorities. Once hemodynamic stability has been achieved and mechanical ventilation discontinued, the patient is transferred to a high-acuity observation or surgical unit. Lung transplant recipients are at high risk for multiple complications. Infections are the leading cause of death, especially within the 1st year after transplant.28 Bacterial bronchitis and pneumonia are the most common infections. CMV, fungi, viruses, and mycobacteria are also causative agents. Noninfectious issues may include VTE, diaphragmatic dysfunction, and cancer. Immunosuppressive therapy usually includes a 3 drug regimen of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), and prednisone. (The mechanisms of action of these drugs are discussed in Table 14.17.) Drug levels are monitored on a regular basis. Lung transplant recipients usually receive higher levels of immunosuppressive therapy than other organ recipients. Acute rejection is fairly common. Between 28% and 64% of patients will have 1 episode of acute rejection in the 1st year after their transplant.29 When acute rejection occurs, it typically occurs in the first 5 to 10 days after the transplant. Signs include low-grade fever, fatigue, dyspnea, dry cough, and O2 desaturation. Accurate diagnosis of rejection is by transbronchial biopsy completed via bronchoscopy. Treatment consists of high doses of IV corticosteroids for 3 days, followed by high doses of oral prednisone. In patients with persistent or recurrent acute rejection, antilymphocyte therapy may be useful. Bronchiolitis obliterans (BOS) is a manifestation of chronic rejection in lung transplant patients. BOS is characterized by airflow obstruction that progresses over time. The onset is often subacute, with gradual development of exertional dyspnea, nonproductive cough, wheezing, and/or low-grade fever. Airway obstruction is not responsive to bronchodilators and corticosteroid therapy. Additional immunosuppressive agents may be used to treat chronic rejection. Because acute rejection is a major risk factor for BOS, preventing acute rejection is key to decreasing chronic rejection. Before discharge, the patient needs to be able to perform self-care activities, including managing their medication plan, and know when to call the transplant team. Patients are taught pulmonary clearance measures, including chest physiotherapy and deep-breathing and coughing techniques to help minimize complications. Home spirometry is used to monitor trends in lung function. Teach patients to keep medication logs, laboratory results, and spirometry records. An outpatient rehabilitation program can improve physical endurance. After discharge, the transplant team follows the patient for transplant-related issues. Patients return to their HCP for health maintenance and routine illnesses. Care coordination among the transplant team, inpatient team, and primary care team is essential for ongoing successful management. Information about organ transplants, histocompatibility, rejection, and immunosuppressive therapy is found in Chapter 14. LUNG CANCER Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States.30 Lung cancer accounts for 25% of all cancer 624 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation deaths, more than those caused by breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined. In 2021, around 235,000 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed, and 131,000 Americans will die.30 Although lung cancer has a high mortality and low cure rate, advances in medical treatment are improving the response to treatment. Etiology Smoking causes 80% to 90% of all lung cancers.31 There is no safe form of tobacco or tobacco product. Using smokeless tobacco, pipes and cigars, hookah and waterpipe, bidis, and kreteks all pose significant risk for lung cancer. Tobacco smoke contains over 7000 chemicals, of which 250 are harmful. Of the harmful substances in tobacco smoke, 69 interfere with normal cell development and are linked to lung cancer. Exposure to tobacco smoke causes changes in the bronchial epithelium. These changes usually return to normal with smoking cessation. The risk for lung cancer gradually decreases with smoking cessation, reaching that of nonsmokers within 10 to 15 years of quitting. The risk for developing lung cancer is directly related to total exposure to tobacco smoke. Measures of exposure include the total number of cigarettes smoked in a lifetime, age of smoking onset, depth of inhalation, tar and nicotine content, and the use of unfiltered cigarettes. Nonsmokers can also develop lung cancer. Sidestream smoke (smoke from burning cigarettes, cigars) has the same carcinogens found in mainstream smoke (smoke inhaled and exhaled by the smoker). This exposure to secondhand smoke creates a health risk for nonsmoking adults and children. Other risk factors include exposure to high levels of pollution, radiation (especially radon exposure), and asbestos. Heavy or prolonged exposure to industrial agents, such as radon, coal dust, asbestos, chromium, silica, arsenic, and diesel exhaust, increases risk, especially in smokers.31 Marked variations exist in a person’s tendency to develop lung cancer. Differences in incidence, risk factors, and survival exist between men and women (Box 30.5). Genetic, hormonal, and molecular influences may contribute to these differences. At the same time, the incidence and survivability vary between racial and ethnic populations (Box 30.6). Pathophysiology We think most primary lung tumors arise from mutated epithelial cells. The growth of mutations, which are caused by carcinogens, is influenced by various genetic factors. Once underway, epidermal growth factor promotes tumor development. Tumor cells grow slowly, taking 8 to 10 years for a tumor to reach 1 cm in size, the smallest lesion detectable on x-ray. Lung cancers occur mainly in the segmental bronchi or beyond and usually occur in the upper lobes. There are 2 broad subtypes of primary lung cancer: non– small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (84%) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (13%) (Table 30.24).32 Lung cancers metastasize mainly by direct extension and through the blood and lymph system. The common sites for metastasis are the lymph nodes, liver, brain, bones, and adrenal glands. BOX 30.5 BIOLOGIC SEX CONSIDERATIONS Lung Cancer Men • Have a 1 in 15 chance of developing lung cancer (smokers and nonsmokers) • Diagnosed with lung cancer more than women • Die from lung cancer more than women • Male smokers are 10 times more likely to develop lung cancer than nonsmokers • Lung cancer incidence and deaths are decreasing in men Women • Have a 1 in 17 chance of developing lung cancer (smokers and nonsmokers) • Lung cancer incidence and deaths are increasing in women. • Develop lung cancer after fewer years of smoking than men • Develop lung cancer at a younger age than men • Nonsmoking women are at greater risk for developing lung cancer than nonsmoking men • Women with lung cancer live, on the average, 12 months longer than men BOX 30.6 EQUITY PROMOTING HEALTH Lung Cancer Blacks • Have the highest incidence of lung cancer • Are more likely to die from lung cancer than any other ethnic group • Have a higher rate of lung cancer among men than in other ethnic groups Whites • Have the 2nd highest death rate from lung cancer • Have a higher rate of lung cancer among women than in other ethnic groups Asians/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics • Have the lowest rates of lung cancer in both men and women Source: American Lung Association: Lung cancer fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www. lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/ lung-cancer/resource-library/lung-cancer-fact-sheet. Other Types of Lung Tumors SCLC and NSCLC account for 97% of lung tumors. The other 3% include: • Hamartomas, the most common benign tumor, is a slow-growing congenital tumor composed of fibrous tissue, fat, and blood vessels. • Mucous gland adenoma is a benign tumor arising in the bronchi. It consists of columnar cystic spaces. • Mesotheliomas are either malignant or benign. They start in the visceral pleura. Malignant mesotheliomas are related to asbestos exposure. Benign lesions are localized. Secondary metastases from other cancers can occur. Cancer cells from another part of the body reach the lungs through the pulmonary capillaries or lymphatic network. The main cancers that spread to the lungs often start in the breast, GI, or genitourinary tract. Paraneoplastic Syndrome Lung cancer can cause paraneoplastic syndrome. Paraneoplastic syndrome may be initiated by hormones, cytokines, enzymes (secreted by tumor cells), or antibodies (made by the body in CHAPTER 30 TABLE 30.24 Type Lower Respiratory Problems 625 Types of Primary Lung Cancer Growth Rate Characteristics Response to Therapy Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Adenocarcinoma Moderate • Accounts for 40% of lung cancers • Most common lung cancer in United States • Most common cancer in people who have not smoked • Found in peripheral areas of lung • Often has no manifestations until widespread metastasis is present Large cell Rapid • Accounts for 10% of lung cancers (undifferentiated) • Composed of large cells that are anaplastic cancer • Often arise in bronchi • Is highly metastatic via lymphatics and blood Squamous cell Slow • Accounts for 25%–30% of lung cancers cancer • Centrally located • Causes early symptoms of nonproductive cough and hemoptysis • Does not have a strong tendency to metastasize Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) Small cell cancer Very rapid • Accounts for about 10%–15% of lung cancers • Very aggressive form of lung cancer • Spreads early via lymphatics and bloodstream • Frequent metastasis to brain • Associated with endocrine problems • Surgical resection may be tried depending on staging • Does not respond well to chemotherapy • Surgery is not usually done because of high rate of metastases • Tumor may be radiosensitive but often recur • Surgical resection may be tried • Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation • Depending on the staging, life expectancy is better than for SCLC • Chemotherapy mainstay of treatment; more responsive to chemotherapy than NSCLC • Radiation used as adjuvant therapy and palliative measure • Overall poor prognosis response to the tumor) that destroy healthy cells. Sometimes, paraneoplastic syndrome manifests before the cancer is diagnosed. Examples of paraneoplastic syndrome include hypercalcemia, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), adrenal hypersecretion, polycythemia, and Cushing syndrome. SCLCs are most often associated with paraneoplastic syndrome. The conditions may stabilize with treatment of the underlying cancer. SIADH, adrenal hypersecretion, and Cushing syndrome are discussed in Chapter 54. Clinical Manifestations The manifestations of lung cancer are usually nonspecific. They may appear late in the disease process. Symptoms may be masked by a chronic cough attributed to smoking or smoking-related lung disease. Manifestations depend on the type of primary lung cancer, its location, and extent of metastatic spread. Lung cancer often presents as a lobar pneumonia that does not respond to treatment. The most common symptom and often the one that is reported first is a persistent cough. The patient may have dyspnea or wheezing. Blood-tinged sputum may be present because of bleeding caused by the cancer. Chest pain, if present, may be localized or unilateral, ranging from mild to severe. Later manifestations include nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and weight loss. Hoarseness may be present due to laryngeal nerve involvement. Dysphagia, unilateral paralysis of the diaphragm, and superior vena cava obstruction may occur because of intrathoracic spread of the cancer. Lymph nodes are often palpable in the neck or axillae. Mediastinal involvement may lead to pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and dysrhythmias. Diagnostic Studies A chest x-ray is the first diagnostic test done for patients with suspected lung cancer. The x-ray may be normal or identify a Fig. 30.10 Lung cancer lesion. (© iStock.com/Sutthaburawonk.) lung mass or infiltrate (Fig. 30.10). Evidence of metastasis to the ribs or vertebrae and a pleural effusion may be seen on chest x-ray. CT scanning is used to further evaluate the lung mass. CT scans can identify the location and extent of masses in the chest, any mediastinal involvement, and lymph node enlargement. Sputum cytology can identify cancer cells, but sputum samples are rarely used in diagnosing lung cancer because cancer cells are not always present in the sputum. A definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy. Cells for biopsy can be obtained by CT-guided needle aspiration, bronchoscopy, mediastinoscopy, or VATS. If a thoracentesis is done to relieve a pleural effusion, the fluid is analyzed for cancer cells. 626 SECTION 6 TABLE 30.25 Lung Cancer Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation Interprofessional Care Diagnostic Assessment • History and physical assessment • Chest x-ray • Bronchoscopy • Cytologic study of bronchial washings or pleural space fluid • Transbronchial or percutaneous fine-needle aspiration • CT scan, MRI, PET • Mediastinoscopy • Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) • Laboratory tests: CBC, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, WBC and differential, liver function tests, calcium chemistries Management • Surgery (segmental or wedge resection, lobectomy, pneumonectomy) • Radiation therapy • Chemotherapy • Targeted therapy and immunotherapy • Prophylactic cranial radiation • Bronchoscopic laser therapy • Photodynamic therapy • Airway stenting • Radiofrequency ablation Accurate assessment of lung cancer is critical for staging and determining appropriate treatment. Bone scans and CT scans of the brain, pelvis, and abdomen assess for metastases. A CBC with differential, electrolyte panel, and liver and renal function tests are done. Sometimes pulmonary function tests may be done. MRI and/or positron emission tomography (PET) may be used to evaluate and stage lung cancer. Table 30.25 outlines the diagnostic assessment and management of lung cancer. Staging Staging of NSCLC is done using the TNM staging system.33 Under the TNM system, cancer is grouped into 4 stages with A or B subtypes. A simplified version of staging of NSCLC is shown in Table 30.26. Patients with stages I, II, and IIIA disease may be surgical candidates. Stage IIIB or IV disease is usually inoperable and has a poor prognosis. Many NSCLCs are not resectable at the time of diagnosis. Staging of SCLC by TNM has not been useful because this cancer is aggressive and always considered systemic. The stages of SCLC are limited and extensive. Limited means that the tumor is only on 1 side of the chest and regional lymph nodes. Extensive SCLC means that the cancer extends beyond the limited stage. Unfortunately, most patients with SCLC have extensive disease at time of diagnosis. Screening for Lung Cancer Many medical groups recommend cancer screening for highrisk patients. Adults ages 50 to 80 with a history of smoking (20 pack-year smoking history or currently smoke) or who quit smoking but less than 15 years ago should have annual screening for lung cancer.34 Screening is done using low-dose CT. TABLE 30.26 Lung Cancer Staging of Non–Small Cell Stages Characteristics 0 I A B II A B III A B C IV A B Cancer cells found in first layer of cells in the respiratory airway or alveoli Tumor is small and localized to lung. No lymph node involvement Tumor <3 cm, minimally invasive Tumor 3–4 cm and invading main airway (but not into right or left bronchi), visceral pleura. Increased tumor size, some lymph node involvement Tumor 4–5 cm with invasion of main airway (but not right or left bronchi), visceral pleura Tumor 5–7 cm involving the bronchus and lymph nodes near bronchi on same side of chest; tumor 5–7 cm with visceral and parietal pleura, diaphragm, phrenic nerve involvement; 2 or more tumors in same lobe of lung Increased spread of tumor 1 or more tumors ≤5 cm or smaller spread to the nearby (same side) structures (chest wall, pleura, pericardium), or metastases into diaphragm, hear, bone, and regional lymph nodes below carina 1 or more tumors >5 cm in the same lung, involving heart, trachea, esophagus, mediastinum; lymph node involvement (same side or opposite side, or below carina), Tumor >5 cm and more than 1 tumor in a different lobe of the lung; lymph nodes on opposite side involved Distant metastasis (to the other lung) Metastases to the other lung, pleura, pericardium; 1 new tumor outside of chest Metastases widespread and 2 or more tumors outside of the chest Interprofessional Care Surgical Therapy Surgical resection is the treatment of choice in NSCLC stages I to IIIA without mediastinal involvement. Resection gives the best chance for a cure. Factors that affect survival include the size of the primary tumor and preexisting co-morbidities. For other NSCLC stages, patients may have surgery in conjunction with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. Surgical procedures include segmental or wedge resection procedures, lobectomy (removal of 1 or more lobes of the lung), or pneumonectomy (removal of 1 entire lung). VATS may be used to treat lung cancers near the outside of the lung. Surgery is generally not done for SCLC because of its rapid growth and dissemination at the time of diagnosis. When the tumor is operable, the patient’s cardiopulmonary status must be evaluated to determine the ability to have surgery. Pulmonary function studies, ABGs, and anesthesia and critical care consults are often done to assess the patient’s cardiopulmonary status and overall surgical risk. Radiation Therapy Radiation therapy may be used as treatment for both NSCLC and SCLC. Radiation therapy may be given as curative, palliative, or adjuvant therapy in combination with surgery, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy. Radiation therapy may be the primary therapy in the person who cannot undergo surgical resection because of co-morbidities. Radiation therapy relieves dyspnea and hemoptysis from CHAPTER 30 bronchial obstructive tumors and treats superior vena cava syndrome. It can treat pain from metastatic bone lesions or brain metastasis. Radiation before surgery can reduce the tumor mass before surgical resection. Complications of radiation therapy include esophagitis, skin irritation, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and radiation pneumonitis (see Chapter 16). Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), or stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), is a type of radiation therapy that uses high doses of radiation delivered to tumors outside the CNS. SBRT uses special positioning procedures and radiology techniques to deliver a higher dose of radiation to the tumor and expose only a small part of healthy lung. It does not destroy the tumor, but damages tumor DNA. Therapy is given over 1 to 3 days. SBRT is an option for patients with early-stage lung cancers who cannot have surgery. Chemotherapy Chemotherapy is the main treatment for SCLC. In NSCLC, chemotherapy may be used to treat nonresectable tumors or as adjuvant therapy to surgery. A variety of chemotherapy drugs and multidrug protocols are used. Chemotherapy for lung cancer typically consists of combinations of 2 of these drugs: etoposide, carboplatin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, vinorelbine, docetaxel, gemcitabine, and pemetrexed (Alimta). Targeted Therapy Targeted therapy uses drugs that block the growth of molecules involved in specific aspects of tumor growth (see Chapter 16). Because this therapy inhibits growth rather than directly killing cancer cells, targeted therapy may be less toxic than chemotherapy. One targeted therapy for NSCLC is tyrosine kinase inhibitors. They block signals for growth in the cancer cells. Agents include cetuximab (Erbitux), erlotinib (Tarceva), afatinib (Gilotrif), gefitinib (Iressa), osimertinib (Tagrisso), and necitumumab (Portrazza). Another type of kinase inhibitor is used to treat patients with NSCLC who have an abnormal anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene. Drugs in this class include crizotinib (Xalkori), brigatinib (Alunbrig), and ceritinib (Zykadia). These drugs directly inhibit the kinase protein made by the ALK gene that is responsible for cancer development and growth. Another targeted therapy used to treat lung cancer inhibits the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) by targeting vascular endothelial growth factor. Bevacizumab (Avastin) is an angiogenesis inhibitor. Immunotherapy Nivolumab (Opdivo), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) are drugs that target PD-1, a protein on T cells that normally helps keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against cancer cells. This can shrink some tumors or slow their growth. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab can be used in people with metastatic NSCLC whose cancer has progressed after other treatments and with tumors that express PD-1. Other Therapies Prophylactic cranial irradiation. Patients with SCLC have early metastases, especially to the CNS. Most chemotherapy Lower Respiratory Problems 627 does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier. As a result, after successful systemic treatment, the patient is at risk for brain metastases. Pro­phy­lactic radiation can decrease the incidence of brain metastases and may improve survival rates in patients with limited SCLC. Bronchoscopic laser therapy. Bronchoscopic laser therapy makes it possible to remove obstructing bronchial lesions. The laser’s thermal energy is transmitted to the target tissue. It is a safe and effective treatment of endobronchial obstructions from tumors. Symptoms of airway obstruction are relieved due to thermal necrosis and tumor shrinkage. The procedure may be repeated as needed. Photodynamic therapy. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a form of treatment for early-stage lung cancers that uses a combination of a drug and a specific type of light. Cancer cells are killed when the drug, known as a photosynthesizer, is exposed to a specific wavelength of light. Porfimer (Photofrin) is the most used photosynthesizer. After an IV injection, it selectively concentrates in tumor cells in the esophagus and outer layers of the airways. After a set time (usually 48 hours), the tumor is exposed to laser light via bronchoscopy, activating the drug and causing cell death. Necrotic tissue is removed with bronchoscopy a few days later. This process can be repeated as needed. PDT can affect nutrient delivery to cancer cells and stimulate the immune system to attack the cancer cells. Airway stenting. Stents are used alone or in combination with other techniques for relief of dyspnea, cough, or respiratory insufficiency. The stent is inserted during a bronchoscopy. The advantage of a stent is that it supports the airway wall against collapse or external compression and can delay extension of tumor into the airway lumen. At this time, we do not know which patients will benefit most from airway stents. Radiofrequency ablation. Radiofrequency ablation therapy is used to treat small NSCLC lung tumors that are near the outer edge of the lungs. This therapy is an alternative to surgery in patients who cannot or choose not to have surgery. A thin, needle-like probe is inserted through the skin into the tumor. CT scans are used to guide placement. An electric current is then passed through the probe, which heats and destroys cancer cells. Local anesthesia is used for this outpatient procedure. NURSING MANAGEMENT: LUNG CANCER Assessment It is important to determine the patient and caregiver’s understanding of the condition, diagnostic tests (those completed as well as those planned), treatment options, and prognosis. Assess the patient’s anxiety level and support available from family and significant others. Subjective and objective data that you should obtain are described in Table 30.27. Clinical Problems Clinical problems for the patient with lung cancer may include: • Impaired respiratory function • Difficulty coping • Pain • Deficient knowledge 628 SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation TABLE 30.27 NURSING ASSESSMENT Lung Cancer Subjective Data Important Health Information Health history: Exposure to secondhand smoke, airborne carcinogens (e.g., asbestos, radon, hydrocarbons), other pollutants. Urban living environment. Chronic lung disease (e.g., TB, COPD, bronchiectasis). History of cancer. Medications: Cough medicines, bronchodilators, expectorants, other respiratory medications Functional Health Patterns Health perception–health management: Smoking history, including what was smoked, amount per day, and number of years. Family history of lung cancer. Frequent respiratory tract infections Activity-exercise: Fatigue. Persistent cough (productive or nonproductive). Dyspnea at rest or with exertion, hemoptysis (late symptom) Cognitive-perceptual: Chest pain or tightness, shoulder and arm pain, headache, bone pain (late symptom) Objective Data Cardiovascular •Pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, dysrhythmias (late signs) General Fever, nose and/or throat infection, neck and axillary lymphadenopathy, paraneoplastic syndrome (e.g., syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion) GI •Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, dysphagia (late) Musculoskeletal •Pathologic fractures, muscle wasting (late) Neurologic •Confusion, disorientation, unsteady gait (brain metastasis) Respiratory •Wheezing, hoarseness, stridor, dyspnea on exertion (unilateral diaphragm paralysis), pleural effusions (late signs) Skin •Edema of neck and face (superior vena cava syndrome), digital clubbing. Jaundice (liver metastasis) Other Possible Diagnostic Findings •Lesions and any metastases found on chest x-ray, CT scan, MRI, PET scan •Positive sputum or bronchial washings for cytologic studies. •Positive fiberoptic bronchoscopy and biopsy findings Planning The overall goals are that the patient with lung cancer will have a (1) patent airway, (2) adequate tissue oxygenation, (3) minimal discomfort, and (4) understanding about the type of lung cancer, and (5) a realistic outlook about treatment and prognosis. Implementation Health Promotion The best way to halt the epidemic of lung cancer is to prevent people from smoking, help smokers stop smoking, and decrease exposure to environmental pollutants. Because most smokers start in the teenage years, prevention of teen smoking has the most significant role in reducing the incidence of lung cancer. A wealth of material is available to the smoker who is interested in smoking cessation. Modeling healthy behavior by not smoking, promoting smoking cessation programs, and actively supporting education and policy changes related to smoking are important nursing activities. Many changes have occurred because we know that secondhand smoke is a health hazard. Laws prohibit smoking in most public places and limit public smoking to designated areas. Acute Care Care of the patient with lung cancer initially involves support and reassurance during diagnostic evaluation. It is important to recognize the multiple stressors that occur when someone receives a lung cancer diagnosis. The stress response is a normal and adaptive response but can become detrimental when stress is overwhelming and intense. Patients have the stress of their symptoms, including dyspnea and cough. Diagnostic and therapeutic interventions provide more stress by placing patients in unfamiliar environments with unusual and perhaps painful procedures. Emotional stressors include waiting for test results and awareness of the high mortality rate from lung cancer. Worries about role performance and ability to care for their family while undergoing cancer treatment provide further stress. Assess every patient since each will have unique stressors. The insight gained will help the patient and caregiver cope with the stress of both illness and treatment. Patient-centered care depends on the diagnosis and plan for treatment. Teach signs and symptoms to report (e.g., hemoptysis, dysphagia, chest pain, hoarseness). Provide comfort, teach ways to reduce pain, and monitor for drug side effects. Teach the patient to recognize signs and symptoms that may indicate progression or recurrence of disease. Be available to listen to the patient and their families. Encourage them to share their thoughts, fears, and concerns. Foster appropriate coping strategies for both the patient and caregiver and help them access resources to deal with the illness. Care of the patient undergoing radiation therapy and chemotherapy is discussed in Chapter 16. CHECK YOUR PRACTICE You are completing discharge teaching with E.S., a 72- year-old patient who had a lobectomy for NSCLC. She tells you, “I’m not going to give up smoking my cigarettes because I am just going to die anyhow. I might as well enjoy smoking while I can.” • How would you respond? Ambulatory Care Counseling patients on smoking cessation and prevention is essential in decreasing mortality from lung cancer. Assess smoking cessation readiness. Some patients may not perceive value in quitting smoking once they have a diagnosis of lung cancer. As CHAPTER 30 nurses, however, we can encourage the patient to perhaps quit or decrease the number of cigarettes smoked per day. We might be able to gain support from family members who may wish to quit smoking with the patient. Explain the importance of maintaining a smoke-free environment in the home, particularly if O2 will be in use. If the treatment plan includes home O2, the teaching plan must include the safe use of O2. For many patients with lung cancer, little can be done to significantly prolong their lives. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy can provide palliative relief from distressing symptoms. Constant pain may become a major problem. Measures used to relieve pain are discussed in Chapter 9. Care of the patient with cancer is discussed in Chapter 16. The palliative care team should be involved as the patient and family move toward the Lower Respiratory Problems 629 end of life (see Chapter 10). Social workers and spiritual care advisors are invaluable in end-of-life situations. The team can provide information about disability, financial planning, and community resources for end-of-life care, such as hospice and home care. Evaluation The expected outcomes are that the patient with lung cancer will: • Have adequate breathing patterns • Maintain adequate oxygenation • Have minimal to no pain • Convey feelings openly and honestly, with a realistic attitude about prognosis Case Study Pneumonia and Lung Cancer Patient Profile J.H. is a 52-year-old male who comes to the ED with shortness of breath. He says it has really increased over the past several months. J.H. has not been to a doctor for many years, as he is often “too busy with work.” His wife told him to get his “cough checked out.” (© iStockphoto/ Subjective Data Thinkstock.) • 38 pack-year history of cigarette smoking • Has had 25-lb weight loss despite a normal appetite in the past few months • Admits to a “smoker’s cough” for the past 2 to 3 years • Recently started coughing up a small amount of blood-tinged sputum • Married and the father of 3 adult children Objective Data Physical Assessment • Thin, pale man who looks older than stated age • Height 6 ft (182.9 cm); weight 135 lb (61.2 kg) • Intermittently confused and anxious • Vital signs: temperature 102.6°F (39.2°C), heart rate 120, respiratory rate 36 (shallow, slightly labored), BP 98/54 • Lung auscultation: Coarse crackles (left upper and left lower lobes) that clear with cough; decreased breath sounds (right middle lobe and right lower lobe) • Chest wall has limited excursion on right side Diagnostic Studies • ABGs: pH 7.51, PaO2 62 mm Hg, PaCO2 30 mm Hg, HCO3− 22 mEq/L • SpO2 saturation 88% (room air) • Chest x-ray: Right lung (RML, RLL) consolidation, with visible mass around right bronchus; small pleural effusion (<150mL) on the right side • Bronchoscopy: Biopsy of mass reveals small cell lung cancer (SCLC) Interprofessional Care • Diagnosis: Pneumonia with SCLC • Follow-up and discuss with patient and family appropriate treatment options Discussion Questions 1. Recognize: How would you classify J.H.’s pneumonia? Why is this ­important? 2. Analyze: Which findings concern you? 3. Analyze: What is your analysis of J.H.’s ABG results? 4. Plan: How would you expect other health care team members to be involved in J.H.’s care? 5. Prioritize: Based on the assessment data presented, what are the priority clinical problems? 6. Prioritize: What are the priority nursing interventions for J.H.? 7. Act: Identify activities that you can delegate to assistive personnel (AP). 8. Act: You are planning a meeting with J.H. and his family at 1400 hours to discuss their needs. The morning of the meeting, the HCP informs you that J.H. is terminally ill. Who will you include in this meeting? 9. Act: J.H.’s children tell you that they are worried they will get lung cancer, since their father has it and they grew up around his secondhand smoke. They want to know what kind of screening is available for them. How will you respond? 10. Evaluate: How would radiation therapy help J.H.? Answers available at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lewis/medsurg. B R I D G E T O N C L E X E X A M I N A T I O N The number of the question corresponds to the same-numbered outcome at the beginning of the chapter. 1.When caring for a patient with acute bronchitis, the nurse will prioritize interventions by a. auscultating lung sounds. b. encouraging fluid restriction. c. administering antibiotic therapy. d. teaching the patient to avoid cough suppressants. 2.Which patient(s) have the greatest risk for aspiration pneumonia? (select all that apply) a. Patient who had thoracic surgery b. Patient with acute opioid overdose c. Patient who had a myocardial infarction d. Patient who is receiving nasogastric enteral feeding e. Patient who has a traumatic brain injury from blunt trauma SECTION 6 Problems of Oxygenation: Ventilation 3.An appropriate nursing intervention to help a patient with pneumonia manage thick, purulent secretions would be to a. perform postural drainage every hour. b. provide analgesics every 3 hours to promote comfort. c. administer O2 as prescribed to maintain optimal O2 levels. d. teach them how to cough effectively and expectorate secretions. 4.A patient with TB is admitted to the hospital and placed in a single patient room on airborne precautions. What should the nurse teach the patient? (select all that apply) a. No visitors will be allowed while in airborne isolation. b. Expect regular TB skin testing to evaluate for infection. c. Adherence to precautions includes coughing into a paper tissue. d. Take all medications for full length of time to prevent multidrug-resistant TB. e. Wear a standard isolation mask if leaving the airborne infection isolation room. 5.When caring for a patient with a lung abscess, what is the nurse’s priority intervention? a. Postural drainage b. Antibiotic administration c. Obtaining a sputum specimen d. Asking the patient about a family history of lung cancer 6.The patient with a right-side pleural effusion has stable vital signs and O2 at 6 L/min via nasal cannula. A right-side chest tube is attached to straight drainage. Which actions would the nurse include in the plan of care? (select all that apply) a. Placing the patient on NPO status b. Administering analgesia as ordered c. Maintaining high-Fowler’s position d. Encouraging deep breathing and coughing e. Monitoring color and amount of chest tube drainage 7.You are caring for a patient with several traumatic injuries after a multiple-vehicle accident. Which assessment finding would lead you to suspect a flail chest? a. Chest-tube is draining bright red blood b. Tracheal deviation to the unaffected side c. Paradoxical chest movement during respiration d. Little to no movement of the involved chest wall 8.When planning care for a patient at high risk for pulmonary embolism, the nurse prioritizes a. maintaining the patient on strict bed rest. b. using intermittent pneumatic compression devices. c. encouraging the patient to cough and deep breathe. d. encouraging a fluid intake of 2000 mL per 8-hour shift. REFERENCES 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics: Deaths and mortality. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. 2.CDC: Fast facts: pertussis. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ pertussis/fast-facts.html. 3.CDC: Vaccine information statement (VIS)-Tdap: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/tdap.html. 9.The nurse would closely monitor patients exposed to a chlorine leak from a local factory for a. pulmonary edema. b. anaphylactic shock. c. respiratory acidosis. d. acute tubular necrosis. 10.Management of a patient after a lung transplant includes which measures? (select all that apply) a. Mechanical ventilation in the early postoperative period b. Assisting with a lung biopsy if acute rejection is suspected c. IV fluid therapy accompanied by accurate intake and output d. Immunosuppressant therapy, which usually involves a 3 drug regimen e. Pulmonary clearance measures, including deep-breathing and coughing 11.Nursing care of a patient with Stage 4 lung cancer would include a. Coordinating a referral to palliative care b. Limiting visitors to decrease infection risk c. NPO status and starting parenteral nutrition d. Avoiding talking about the cancer diagnosis 1. a; 2. b, d, e; 3. d; 4. c, d, e; 5. b; 6. b, c, d, e; 7. c; 8. b; 9. a; 10. a, b, c, d, e; 11. a. 630 For rationales to these answers and even more NCLEX review questions, visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lewis/medsurg. EVOLVE WEBSITE/RESOURCES LIST http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lewis/medsurg Review Questions (Online Only) Key Points Answer Keys for Questions • Rationales for Bridge to NCLEX Examination Questions • Answer Guidelines for Case Study Student Case Studies • Patient With Lung Cancer • Patient With Pulmonary Embolism and Respiratory Failure Nursing Care Plans • eNursing Care Plan 30.1: Patient With Pneumonia Conceptual Care Map Creator Audio Glossary Content Updates 4.CDC: Pertussis (whooping cough): diagnosis confirmation. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/diagnostic-testing/diagnosis-confirmation.html. *5.World Health Organization (WHO): WHO reveals leading causes of death and disability worldwide: 2000-2019. Retrieved from https://www. www.who.int/news/item/09-12-2020-who-revealsleading-causes-of-death-and-disability-worldwide-2000-2019. *6.Modi AR, Kovacs CS: Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis, management, and prevention, Clev Clin J of Med 87:633, 2020. CHAPTER 30 7.Saha BK: Rapidly progressive necrotizing pneumonia: remember the streptococcus anginous group! Retrieved from https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7406454/. *8.Salzer HJF, Schafer G, Hoenigl M, et al: Clinical, diagnostic, and treatment disparities between HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected immunocompromised patients with pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Retrieved from https://www.karger.com/ Article/Pdf/487713. 9.Einsele H, Ljungman P, Boeckh M: How I treat CMV reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Blood 135:1619, 2020. *10.Karakioulaki M, Stolz D: Biomarkers in pneumonia-beyond procalcitonin, Int J Mol Sci 20:2019, 2004. *11.Warren C, Medei MK, Wood B, et al.: A nurse-driven oral care protocol to reduce hospital-acquired pneumonia, AJN 119:44, 2019. 12.WHO: Tuberculosis. Retrieved from https:// www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. 13.CDC: Fact sheet: Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/ drtb/mdrtb.htm. 14.Massachusetts Department of Public Health: Booster or recall effect and two-stage tuberculin skin testing. Retrieved from https://www.mass.gov/service-details/booster-or-recall-effectand-two-stage-tuberculin-skin-testing. *15.Zhou G, Luo Q, Luo S, et al.: Interferon-γ release assays or tuberculin skin test for detection and management of latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Lancet Infect Dis 20:1457, 2020. *16.Pradipta IS, Houtsma D, van Boven JFM, et al: Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41533-020-0179-x. 17.CDC: Tuberculosis fact sheet: special considerations for treatment of TB disease in persons infected with HIV. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/treatment/treatmenthivpositive.htm. 18.CDC: Fungal diseases: where valley fever comes from. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/ causes.html. 19.Kamangar N: Lung abscess clinical presentation. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/299425-clinical. 20.Wong AW, Ryerson CJ, Guler SA: Progression of fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Retrieved from https://respiratory-research. biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-020-1296-3. Lower Respiratory Problems 631 21.Lee J: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Retrieved from https://www. merckmanuals.com/en-ca/professional/pulmonary-disorders/ interstitial-lung-diseases/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis. 22.Duffett L, Castellucci LA, Forgie MA: Pulmonary embolism: update on management and controversies. Retrieved from https:// www.bmj.com/content/bmj/370/bmj.m2177.full.pdf 23.Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, et al: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Retrieved from https:// erj.ersjournals. com/content/53/1/1801915. 24.Yaghi S, Novikov A, Trandafirescu T: Clinical update on pulmonary hypertension, J Invest Med 68:821, 2020. 25.University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Retrieved from https://www.uwhealth.org/thoracic-surgery/primary-and-secondary-pulmonary-hypertension/11358#. 26.American Cancer Society: Risk factors for malignant mesothelioma. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/malignant-mesothelioma/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html. 27.Cheronis N, Rabold E, Singh A, et al.: Lung transplantation in COPD, Crit Care Nurs Q 44:61, 2021. 28.Bos S, Vos R, Van Raemdonck DE, et al.: Survival in adult lung transplantation: where are we in 2020? Curr Opin Organ Transplant 25:268, 2020. *29.Parulekar AD, Kao CC: Detection, classification, and management of rejection after lung transplantation, J Thorac Dis 11:S1732, 2019. 30.American Cancer Society: Key statistics for lung cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/ key-­statistics.html 31.CDC: Lung cancer: what are the risk factors for lung cancer? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/risk_factors.htm. 32.Bohnenkamp S, Lacovara J: Non-small cell lung cancer: Part 1, Med-Surg Nursing 29:411, 2020. 33.Lababede O, Meziane MA: The eighth edition of TNM staging of lung cancer: Reference chart and diagrams, Oncologist 23:844, 2018. *34.US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement, JAMA 325:962, 2021. *Evidence-based information for clinical practice.