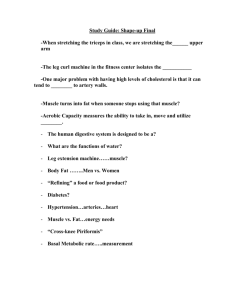

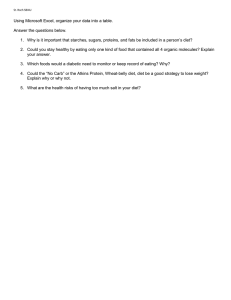

Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific Eating Renaissance Woman D r. J e n n i f e r C a s e , D r. M e l i s s a D a v i s & D r. M i k e I s r a e t e l Renaissance Woman Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific Eating D r. J e n n i f e r C a s e , D r. M e l i s s a D a v i s & D r. M i k e I s r a e t e l Table Of Contents About The Authors 4 01. The Five Basic Principles 15 02. Dieting Procedures For Fat Loss50 03. Dieting Procedures for Muscle Gain80 04. Performance Dieting Strategies 104 05. The Psychology of Dieting 137 06. Female Health Issues Across the Lifespan 191 07. Female Challenges & Expectations 217 08. Fads & Fallacies In the Female Diet World 234 P. 0 4 About The Authors Renaissance Periodization is a diet and training consultation company. RP’s consultants (including the authors of this book) write diets and training programs for every kind of client. RP works with athletes trying to reach peak performances, businesspeople that need more energy at work, and people from all walks of life who want to look and feel better. Jennifer Case Dr. Jennifer Case holds a PhD in Sports Nutrition and is a Registered Dietitian (RD). She was formerly a professor of Exercise Science at the University of Central Missouri, where she taught exercise prescription, functional anatomy, and other Kinesiology courses. A former MMA Fatal Femmes World Champion, Jen is the 2014 IBJJF Master World Champion in the Purple Belt division, both for her weight class and absolute, and the Brown Belt Absolute Pan Am champion. She is currently a brown belt under Jason Bircher at KCBJJ in Kansas City. When Jen is not working with her diet clients at Renaissance Periodization, training or competing, she likes to spend time with her friends and beloved pets (2 cats, 2 dogs), and has been described as “the most world’s most bad-ass butterfly enthusiast” for her perennial attendance to many of the nation’s top butterfly exhibits. P 5 Melissa Davis Dr. Melissa Davis holds a PhD in Neurobiology and Behavior. She is currently a neuroscience researcher at UC Irvine where she studies plasticity and cortical development. Her research has been featured in Scientific American (2013, 2015); published in a host of high impact, peer reviewed journals; and recognized by faculty of 1000. Melissa is the 2015 IBJJF Master World Champion in the Purple Belt division, both for her weight class and absolute and represented the United States for her division in the prestigious Abu Dhabi World Pro Competition in 2015. She is currently a brown belt under Giva Santana at One Jiu Jitsu in Orange County. She has taught neuroscience in an academic setting and coached women in submission grappling and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu in a sports setting. Melissa also helps Renaissance Periodization clients as a personal diet coach. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 6 Michael Israetel Dr. Michael Israetel holds a PhD in Sport Physiology and is currently is a professor of Exercise and Sport Science at Temple University in Philadelphia, where he teaches Nutrition for Public Health, Personal Training, Advanced Strength and Conditioning, Advanced Sports Nutrition, and Exercise, Nutrition, and Behavior. He has worked as a consultant on sports nutrition to the U.S. Olympic Training Site in Johnson City, TN. Mike has coached numerous powerlifters, weightlifters, bodybuilders, and other individuals in both diet and weight training. Originally from Moscow, Russia, Mike is a competitive powerlifter, bodybuilder, and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu grappler. P 7 About Renaissance Periodization Renaissance Periodization is a diet and training consultation company. RP’s consultants (including the authors of this book) write diets and training programs for every kind of client. RP works with athletes trying to reach peak performances, businesspeople that need more energy at work, and people from all walks of life who want to look and feel better. When he founded RP, CEO Nick Shaw had a vision for a company that delivered the absolute best quality of diet and training to its clientele. By hiring almost exclusively competitive athletes that are also PhDs in the sport, nutrition, and biological sciences, Nick has assembled a team of consultants that is unrivaled in the fitness industry. In addition to training and diet coaching, the RP team also writes numerous articles and produces instructional videos on diet, training, periodization science, and all matters involving body composition and sport. Visit us at renaissanceperiodization.com, email at nick@renaissanceperiodization.com. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 8 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Lori Shaw for her thorough text editing and James Hoffmann for literature research and populating the references. We would also like to thank all of our wonderful clients who sent us their pictures. All of the photographs in this book are of actual Renaissance Periodization clients and consultants and not fitness models. We believe your progress using our scientific principles speaks for itself and we wanted to represent the diverse women and athletes that make up our amazing clientele. We particularly appreciate Jennifer Pope of Jennifer Pope photography in the Bay Area, CA who sent us a heap of amazing high quality photos. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 9 Preface W hy a b o o k fo r wo me n? When sports competition first became popular for the general public around the turn of the last century, it was an activity reserved almost exclusively for men. It may seem strange to us now – in the current age of iconic female MMA fighters, weightlifters, and CrossFit athletes – but the idea that women were too fragile for sports prevailed in popular understanding for a long time. As late as 1967, Katherine Switzer, the first female to officially complete a marathon, was nearly run off the course by men protesting her participation on the basis that ‘women could not run that far’. We have come a long way since. Female participation in sports has increased at a nearly exponential rate. Now, a little past the turn of the current century, almost all major sports have a large female participation. The mode of female participation in sports has evolved as well. It used to be that cardio was the domain of the female athlete or enthusiast, with heavy lifting and strength sports left to the boys. Women began venturing into the world of muscle building and competitive sports not too long ago, and have never looked back. Today, a huge fraction of those seeking to lose fat, build muscle and enhance their performance in a variety of sports, are women (slowly putting to rest the stereotypically feminine and ill defined “get toned” goals of women of yesteryear). Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 10 While the participation of women in fitness has skyrocketed, the majority of fitness information purveyed is still geared towards a male audience. In much of the fitness industry today, fitness articles and books are written for men, by men. Those marketed to females are often the equivalent of a t-shirt cut for a man and made with pink fabric – retooled to appeal to her, but unchanged. That’s not the end of the world though - male and female physiology is very similar and most of the guidelines written for men will apply just as easily to women. There are, however, some challenges and circumstances that are unique to the female fitness experience, and, until now, a comprehensive and scientifically backed guide to these issues has been sorely lacking. To date, many of the articles written by women and for women focus on just getting women into training and dieting. What is missing is a resource to address technicalities that concern women who have already been thoroughly inducted, women who are now looking for diet and training to optimize physique, improve performance, and give them a competitive edge. “Lifting won’t make you manly” is a fine article topic, and has an important role in shifting public understanding, but how about some info on how to best go about fine-tuning your training or diet as an experienced female athlete? In addition to being rather general and introductory in nature, a large portion of female fitness writing is authored by female competitors or enthusiasts and not by academics in the field. In fact, a huge subset of popular female-fitness writing is produced by beginners and describes their experiences from a novice point of view. There is absolutely nothing wrong with those perspectives, but there is also a need for a more advanced take. If you are already training and already dieting, there are female authors who have both the years of experience as women in athletics and the multiple advanced degrees to help guide you to the next level of body composition and performance. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 11 This book is just such a guide; it was written by women with the female perspective in mind and its intended purpose is to help you get the most out of your sports nutrition. Specifically, it was written for intelligent women who would like to further their education in nutrition, for the sports and fitness activities to which they give so much of their time, energy, and passion. If you have had your fill of opinion articles by self-appointed Instagram “models” and are ready for a deeper look into scientific dieting, this book is for you. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 12 What scientific dieting can do for you This book is about the scientific approach to dieting and how it applies specifically to female athletes and women on the fitness journey. This book is grounded in science for one simple but important reason; science is the surest path to the truth. Now, science is not the only path to the truth, but because science controls investigations rigorously, its conclusions are much more likely to be an accurate representation of the way things actually work than any other method of observation or intuition. Knowledge obtained through traditions, experience, and educated guesses can work sometimes, but are just not as reliable and informative as knowledge gleaned from controlled scientific study. Here is an example. Sally moves to a new town and decides its time for a new start. She reads online that eating beets at night reduces belly fat and figures it can’t hurt to give it a shot (after all, it was discovered by a mom and Dr.’s don’t want you to know about it – it must be good). Sally sets about religiously eating beets every night and after a couple months, her belly fat is visibly reduced. She concludes that beets are the answer, writes a blog, and encourages everyone to do the same with her stunning before and after photos. Here is the problem – this is an anecdote or a single case in which other variables (changes that could affect outcome) were not assessed or controlled for. What you do not see in the blog is that, when Sally moved, she went from a suburb where she drove everywhere to an urban area where she walked to work every day, and to the store on the weekend. All of that extra walking increased her daily caloric burn, causing her to lose fat all over (she just focused on belly fat changes because that was her expectation or bias). So, the actual truth is that had she moved and not eaten beets every night, the same and possibly greater results (she would have been less the beet calories) would have occurred. In a scientific study of whether eating beets at night reduces belly fat, a large group of women would have been sampled and asked about their exercise habits before and after to check for changes. Other eating habits and any variables that could affect outcome would Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 13 have been checked before and after the start, so that the independent effect of beet eating could be measured. In a controlled study like this, the majority of the women would not have had belly fat reduction and the correct conclusion would have been revealed – eating beets at night does not reduce body fat. In fact – the scientific study might have even shown that women eating beets at night gain body fat (since they were adding calories to their normal diet), though where on their bodies (belly or otherwise) has everything to do with genetics and nothing to do with food type. Recommendations derived from anecdotes (one person’s personal account) and intuition may work for you one time, but fail to produce the same results the next time. Non-scientific advice might have worked for your friend, but have no effect when you try to apply it to your own diet. On the other hand, the knowledge about dieting derived from multiple, replicated scientific studies provides a set of dependable principles. Putting these principles to use will result in effective and fairly predictable changes for every woman on earth who does not violate the laws of thermodynamics (I have yet to meet a woman, or man for that matter, who does this). These dietary principles are a set of basic rules, about the way the body responds to dieting, that form an incredibly effective and superbly reliable guide to eating for fat loss, muscle gain and performance. It is these rules that the majority of this book is based upon, and because these rules are derived from the process of scientific investigation, they are going to work in nearly every conceivable situation to produce real and meaningful results. In the first chapter, we will take a look at what these principles are (there are five of them) and we will derive straightforward dietary recommendations from them, recommendations that can be put right to work to design and refine high performance diets. Preface F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 14 P. 1 5 01 The Five Basic Principles The construction of a maximally effective diet for fat loss, muscle gain, weight maintenance and performance is based on five principles. These principles instruct the ways in which diets need to be designed in order to produce the best results, as well as the ways in which they need to be altered to keep the results coming when stagnation is encountered. We will go over these principles in detail in this chapter. Chapter One The construction of maximally effective diets for fat loss, muscle gain, weight maintenance and performance is based on five principles. These principles instruct the ways in which diets need to be designed in order to produce the best results, as well as the ways in which they need to be altered to keep the results coming when stagnation is encountered. THESE PRINCIPLES ARE 1. Calorie Balance 2. Macronutrient Amounts 3. Nutrient Timing 4. Food Composition (Including Micronutrient Content) 5. Supplements While all five of these principles are important, they are not all equally important with regard to results. That is, some of them are critical to follow when designing even a moderately effective diet, some are just small details and won’t change the big picture of results much, and others fall somewhere on the spectrum in between critical and minor. Another way of looking at these principles is as priorities; When you have a limited ability to focus on diet planning and execution, the most effective diet principles form the top priorities, the least effective form the lowest priorities, and so on. When we compute the actual effects each principle has on the results of a diet, we get the following ratio of effects: Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 16 Diet i n g Fo r Pe r fo r ma n ce & A p p e a ra nce Figure 1. The Diet Principles as Priorities As you can tell from Figure 1, calorie balance accounts for roughly 50% of the effect of any diet, macronutrient amounts account for around 30%, and nutrient timing for 10% or so, with composition and supplements coming in as 5% details to focus on only when the top principles have already been put in place. Ok, so calories are super important and the other stuff matters too, but what is it about calorie balance that makes it so important? Let’s take a look at the basics of calorie balance next, after which we will dive into the details of the other four principles. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 17 Calorie Balance Calorie balance is the amount of calories you consume versus expend every day. If you are hypocaloric for the day, it means you expended more calories than you took in. In every single studied instance (and in accordance with the 3 laws of thermodynamics), a hypocaloric diet leads to tissue loss, which is usually a loss of fat tissue, but can be muscle tissue loss as well. You may not notice a day’s worth of hypocaloric weight loss, but if you consistently run a caloric deficit for days and weeks on end, the weight loss will become detectable on the scale and visible on your body. If you eat just as many calories as you expend, then you are eating an isocaloric diet. In this case, you will neither gain nor lose net tissue weight. When your weight stays the same for weeks on end, not every day is truly isocaloric, as some days will have more or less eating or activity, but on the net balance, the average for the week is isocaloric, thus the result is a maintained body weight. Lastly, you are hypercaloric when you take in more calories than you expend. In this case, you will gain weight, and such gains will become clearly evident over the course of days and weeks of consistently hypercaloric dieting. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 18 We already stated this, but it’s worth emphasizing; Calorie balance accounts for about 50% of the success rate of any diet. That’s a HUGE chunk, and there is a very good reason for this. The single biggest factor in fat loss is whether or not you have a calorie deficit. If you don’t eat enough food to meet all of your body’s needs, it uses body fat to meet the shortfall in supply. That’s actually probably why body fat has developed evolutionarily as a standard part of physiology, a backup energy store during hypocaloric conditions is great for survival in non-modern conditions. You do not generally lose fat on an iso or hypercaloric diet, there is simply not much demand by the body’s tissues for the extra calories from body fat, so it remains (or increases). Yes, you can gain muscle and lose fat at the same time on an isocaloric diet by training so hard and eating so well that most of the food you eat goes to your muscles, and your fat tissue is still starved and has to be used up for energy. However, this almost never happens in any meaningful way for people who have already been training for longer than several years and who already follow a decent diet (and by “decent” we mean, not Twinkies for most meals of the day). In addition, this process is incredibly slow and inefficient for both muscle gain and fat loss. Thus, if fat loss is your goal, a hypocaloric diet is absolutely your best weapon; conversely, if you want to gain muscle, a hypercaloric diet is by far the most effective means of doing so. Trying to do both at once makes both results needlessly more difficult (if not nearly impossible) to attain. Just as with fat loss, calorie balance is the single biggest factor in successfully accomplishing muscle gain with your diet. Only when you eat more food than you need does your body have the excess calories it needs to build a bit of muscle. In our ancestral environment, starvation was always a risk and extra food was not always around. Body fat is an efficient way to save up calories for later periods of deprivation (much better than muscle), so your body doesn’t like to let this reserve go easily and it also doesn’t like to spend energy building muscle - the less efficient and more metabolically costly storage system. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 19 Thus, in order for your body to relax enough and be ok with giving some calories towards muscle growth, a situation of excess calories is needed. Only if the body has extra calories around does it really get muscle growth going, because having more muscle than you need for survival is metabolically expensive - extra muscle burns extra calories - and to the logic of your evolutionarily developed body, this is a dangerous waste and not something it is programmed to do by default. As mentioned, you can gain muscle while in an isocaloric and possibly even hypocaloric environment, but the rates at which this occurs are incomparably smaller than in a hypercaloric environment, and pretty close to impossible for more experienced trainers and dieters. If you want to lose fat, your best weapon is a hypocaloric diet. If you want to gain muscle, your best weapon is a hypercaloric diet. A very simple implication of this is that you cannot do both at the same time, and thus you should have distinct phases of fat loss and distinct phases of muscle gain. If you try to do both at once, you end up in an isocaloric diet and then you get neither advantage! In later chapters on fat loss and muscle gain strategies, we will take a very close look at calorie levels – including, what isocaloric means for different people, and by how much we have to cut or add calories in order to lose fat and gain muscle at the best rates. For now, on to the second most important principle: macronutrients. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 20 Macronutrients By accounting for roughly 30% of diet success, macronutrient amounts are a very large piece of the body composition and performance puzzle. When we say ‘macronutrients,’ we are referring to the three main energy sources required in large amounts by the body: proteins, carbs, and fats. The term ‘Macronutrient amounts’ refers to the separate amounts of each that contribute to the overall sum of calories in a diet. Let’s go through each nutrient and describe its importance and role in the body as well as its recommended intake. For a much more indepth discussion of roles and recommendations, including intricate discussions of minimum and excessive macronutrient intakes, please check out the original Renaissance Diet book. P ro t e i n Protein molecules are specific arrangements of amino acids. Because of their specific arrangements, different proteins are capable of doing different tasks, and proteins in the form of enzymes facilitate some aspect of nearly all important functions in the body. While these functions include cellular transport, forming body structures and constructing most of the nervous system, for our purposes, the most important function of proteins is their role in muscle tissue. That last sentence is perhaps one of the biggest understatements of this book. Protein does not just have “an important role” in muscle building… it literally IS the building block of muscle. The fibers and components of muscle that produce movement and force are themselves protein (actin and myosin, to be specific). Thus, if having, maintaining, or building muscle is your goal, protein is of primary importance; something like the importance of steel and concrete to the function of a skyscraper. Because protein literally constructs muscle, along with all of the enzymes (molecular machines) that help to build and repair muscle, the athlete interested in Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 21 body composition and performance needs plenty of it. In general, hard-training female athletes and fitness enthusiasts need just under 1g of protein per pound of lean body mass per day. Much less than this will reduce muscle growth, and impair muscle maintenance and recovery. Much more than this recommended amount just contributes to excess calories that could be better spent on other macronutrients. What does “per pound of lean body mass” mean, exactly? Well, lean body mass is the amount of non-fat mass (muscle, organs, bone, blood and so on) that an individual carries. Thus, if we have a 150lb female that carries 20% fat (a rather lean and athletic physique), then she’s going to have roughly 30lb of fat tissue (20% of 150 is 30: 150 x 0.20 = 30). When we subtract this fat tissue away from her total mass, that gives us her lean body mass (LBM): 120lbs. Thus, for her to get near-optimal protein intake per day, her daily total protein intake should sum up to around 120g of protein (120lbs x1g). For all of the fat loss and muscle gain diets we will look at designing later, 1g / lb body weight will be our base standard for protein intake. Ca r b o hyd ra t e s While protein is the single most important building block of muscle tissue, carbohydrate is the single most important source of energy. In particular, carbs are the best source of energy for athletic and high intensity activities. Whereas fat is a perfectly fine fuel source for keeping the body functioning while sitting, standing, or in leisurely activity, carbohydrates are by far the body’s preferred fuel source for more intense activities such as running, biking, swimming, lifting, gymnastics, and most other sport and training tasks. Low carb diets are notorious for decreasing athletic performance and training productivity for this very reason. Not only do carbs provide energy for the activity you’re going to do next, they are the primary refueling source for recovery from activities you just did, so that Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 22 you can have plenty of energy the next time you are active. The most dominant source of carbs for high intensity work is in a stored form in the muscle (and a bit in the liver) called glycogen. Glycogen is a giant molecule of glucoses packed together, and glucose molecules (the most fundamental component of all carbs) are broken off of it to be used for energy. The glycogen stored in muscle is the single most important source of glucose, thus it depletes the most after hard training. Taking in carbs after hard training repletes stores of glycogen and allows you to recover and train hard again, whether that be later that day or a few days down the road. Because carbs allow you to keep training hard, they offer several advantages for performance and body composition: • They provide the best energy source for high performance activities • They recover you so that you can perform day in and day out • The resulting ability to train hard increases the adaptive potential of the exercise, facilitating muscle growth • The resulting ability to train hard prevents muscle loss when fat loss is occurring • The very presence of high glycogen levels in the muscle cell turns up musclebuilding machinery in that cell, while a lack of glycogen turns that machinery down As you can see, carbs are of very high importance to performance and body composition - not quite as important to body composition as protein, but at least as important to performance, if not more so. How much carbohydrate does a female athlete and fitness enthusiast need? Unlike with protein, just LBM is not enough for this calculation. Carb intake varies based on LBM, but also on the amount of daily activity that the individual is undertaking, including both formal training and day-to-day tasks. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 23 As you can see from the table below in Figure 2, how much carbohydrate you take in per day can vary greatly in accordance with your daily training and activity level. This means that women of a similar size may be consuming very different amounts of carbs based on their different training and activity levels, and that the same woman can be consuming very different amounts of carbs on the different days of the same week, depending on when she is more or less active. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 24 The more activity a woman performs per day, the more carbohydrate intake she can benefit from. The following is a general guide to carb intake in relationship to activity levels: ACTIVITY LEVEL S edentar y (wor k from ho me, office wor k, a relax ing day off ) R E C O M M E N D E D DA I LY CARB INTAKE 0-0.5g per lb LBM Light Activi ty (u p to 45 minu tes of hard training per day, cou pled wi th a sedentar y or lightly- active wor k/home 0.5-1.0g per lb LBM environment) Modera te Activi ty (u p to 1.5 hour s of hard training per day, wi th u p to a fair ly active wor k/home environment 1.0-1.5g per lb LBM w here you’re on your feet a good par t of the day) Hard Activi ty (1.5-2.5 hour s of hard training per day, cou pled wi th u p to a fu lly active wor k/home environment w here you’re on your feet and doing physica l wor k mos t 1.5-2.0g per lb LBM of the day) Ver y Hard Activi ty (2.5+ hour s of hard training per day, of ten including endurance spor t training and/or a ver y physica l job w hich necessi ta tes being u p and a bou t through the major i ty of the day, including hard physica l 2.0-3.0g per lb LBM tasks such as factor y wor k, cons tr uction, in-per son coaching and fi tness class ins tr uction, etc.) Figure 2. Recommended daily carb intake by activity level Fa t s While proteins and carbs definitely steal the show in terms of their importance towards body composition and performance results, fats are our last, but still important macronutrient to consider in building a diet for body composition Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 25 and performance. Fats are utilized by the body to form important hormones, to construct important parts of all cells (especially those of the nervous system), and to insulate and cushion our joints from the constant pounding they receive during training and competition. Fats do not benefit us in any additional ways just by themselves so long as we meet a minimum standard of intake per day. That is, there is no actual recommended amount for fats. One simply calculates fat needs by summing up the calories taken in from protein and carbs, and then eating the remainder in fats. Thus if you need 2000 calories a day and your proteins and carbs sum up to 1500 calories, then you need 500 calories from fat. Because fats have about 9 calories per gram, this means that for that day you will be consuming about 55g of fat (500/9). The minimum intake of fats for regular, sustained maintenance dieting is likely around 30% in grams per pound of your LBM in most cases. Thus, our 150lb woman with 20% body fat needs around 36g (120 x 0.3) of fat per day. For short periods (up to 2 months), 10% in grams per pound of LBM are acceptable, but much lower than that will have negative effects on training volume and intensity, as well as muscle retention, metabolism speed, and fat loss. Now that we have our calorie balance and macronutrients figured out, we have 80% of the daily nutrition puzzle pieces in place! Let’s move on to our most important smaller detail of dieting; nutrient timing. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 26 Nutrient Timing While nutrient timing is categorized under one topic, it actually consists of three distinct considerations: • How far apart should meals be spread? • How many meals should be consumed per day? • Should we be eating in any special way in relation to times of activity or inactivity? Let’s go through each consideration separately and come up with recommendations from the scientific literature and practical application. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 27 1 ) MEAL SP REA D No matter how many meals you eat throughout the day, the first question we must answer in the design of meal timing is with respect to meal spread. The two ends of the spectrum of options are: • Meals spread evenly throughout the day with relatively even spacing between them • Meals eaten mostly during the morning, afternoon, or evening with less focus on intake at other times of the day Muscle growth and the prevention of breakdown are continuous processes. Put another way, muscle growth after a workout happens over days of constant amino acid influx into the muscle; Muscle breakdown, if it happens, does so over long stretches of time, in most cases, as well. In order to supply the amino acids needed to promote growth and prevent loss, a relatively constant amount of them must be available in the bloodstream at any given time so the muscle cells have ready access. This means that the best likely recommendation for meal spread is to have meals relatively evenly throughout the 24 hour feeding cycle. For example, if you wake at 8am and go to sleep at 12am, 4 meals, each at 8am, 1:30pm, 7pm and 12am is s reasonable timing split, as opposed to 12pm, 4pm, 8pm, and 11pm, which leaves a 17 hour fasting window each night and morning. Simple implication: whatever number of meals you have during a day, try to spread them fairly evenly. 2 ) MEAL N UMB ER If we’re looking to spread amino acid titration out of the GI tract fairly evenly, we must also be concerned with how many meals we are consuming across the day. No matter how big a single meal is, the contents of that meal will take no more than 12 hours to digest completely in most cases. Thus if you eat ALL of your Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 28 daily intake in one sitting at 8am (which would be both impressive and scary), your muscles will still be lacking in amino acids from 8pm until your next snakelike meal at 8am the next day. If you eat two meals a day, the spread gets better, but because the meals are smaller by half, their digestion time also speeds up, so that now maybe instead of 12 hour gap, you have an 8 hour gap in amino acid availability. As we add more meals in, we lessen the gap in amino acid availability until it gets fairly ideal - somewhere around 4-6 meals per day. At this point, the gap is so small that muscle loss is minimal, and in fact, a small amount of exposure to an amino acid-free environment fires up muscle building machinery during the next meal - so much so that if any small amount of muscle was lost between meals, it is gained back. At around 7 meals per day, amino acids essentially titrate around the clock with no interruptions. Thus eating more than 7 times per day without an extenuating circumstance is not needed and would be pretty inconvenient. What does all of this mean? From the perspective of body composition, anywhere between 4 and 7 meals per day is a very good place to start for meal frequency. Anything much less than 4 will start to cost muscle, and anything much more than 7 offers no additional advantages and just makes life less convenient. 3 ) T IMIN G IN REL AT IO N TO AC TI VI T Y The research on timing in respect to physical activity tells us several important things • Protein timing does not affect performance and recovery, so long as protein intake is spread evenly through the day • For training longer than 1 hour, carbs and protein consumed during training improves performance and saves muscle tissue from being broken down • Carbs eaten in the several meals after training are much more likely to be assembled into muscle glycogen and to improve the next workout’s performance than they are to be stored as fat, especially compared to eating the same amount of carbs at other times of the day Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 29 • Carbs in the meal before training reliably improve performance • Fat intake slows, by a considerable magnitude, the digestion and absorption of all other nutrients eaten in that meal Ok, so from the information above, we don’t need to worry about timing protein intake in any special way – we just spread that consumption out over the day. What we absolutely do need to focus on, is on structuring carb timing. Based on these concepts, we can recommend that having some carbs in the meal before training (1-3 hours before in most cases) is a good idea to optimize workout energy and productivity. Something like 15% of the daily carb total is likely a good idea here. We can also recommend that during and post workout (up to about 6 hours after the conclusion of the workout) is where most of our carbs should be consumed, with about 70% of total daily carbs being taken in here if body composition and performance is the goal. The remaining 15% or so of carbs allotted for that day can be spread among the meals that are far outside of the workout window. Since fat intake slows the digestion of other nutrients, having too much fat in the meal just before training can delay digestion until during training, which produces two undesired outcomes: first, we don’t get those pre-workout carbs when we need them, and secondly, we risk some GI discomfort as blood flow is directed away from the stomach and to the working muscles, leading to an increased chance of nausea as the digestion rate slows and the food just ends up sitting there. In much the same way, fat during and right after training delays the appearance of carbs in the blood and thus the muscles, interfering with glycogen repletion and ultimately, recovery. For these reasons, we can recommend that fat intake needs to be lower pre, during, and post-training, with most fats for the day being consumed outside of the workout window. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 30 TO RECAP TIMING, JUST FOLLOW THESE SIMPLE RECOMMENDATIONS • Eat your meals spread evenly through the day • Eat between 4 and 7 meals per day when you can • Have most of your carbs pre, during and post-workout • Have most of your fats in the meals of the day furthest away from your workouts By following these guidelines, you can get a bit more out of your diet, perhaps around 10% more effect for body composition and performance. Not a huge deal, but an important detail. Now that we have timing pretty well squared away, it’s time to follow those rules with just soy protein shakes, Oreos, and bacon! Yay! Wait, does the KIND of food we consume to get our proteins, carbs and fats matter? Let’s find out in the next section on food composition! Food Composition How much we eat (calories) is by far the most important factor we can control. What we eat (macronutrients) matters a lot, and when we eat (timing) is a small but important detail. Much less important but still impactful is the question of where our eaten macronutrients come from. Coming in at roughly 5% of the total effect of the diet on body composition and strength, food compositions tells us where we are getting our proteins, carbs, and fats and how that matters for results. Let’s take a look at each nutrient separately: 1 ) P R OT EIN Protein composition, otherwise known as protein quality, determines to what Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 31 extent eaten proteins are fully digested, absorbed and used to make and preserve muscle tissue. Proteins with the highest quality have the best effects on muscle mass; proteins with the lowest quality have a good, but measurably smaller effect. Here is a list of some common protein sources in descending order of their quality: • Whey Protein • Egg Protein • Chicken Breast • Soy Protein • Peanut Protein • Brown Rice Protein Generally speaking, milk proteins are the highest quality, followed by egg and animal proteins. Complete plant proteins like soy are lower in quality, and incomplete plant proteins like brown rice proteins are the lowest quality. Getting Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 32 most of your protein from higher quality sources likely has a very small, but significant, effect on muscle size gain and retention. When you stray from the recommended quality protein sources like those at the top of the list above, and instead, find yourself reaching for a protein bar on the go, or if you decide you want to mix it up by buying some protein pancake mix, you might want to take a minute to assess protein quality. When reading food labels and determining the amount of protein in something you are considering as your protein source, also check out the ingredient list to see where the protein comes from. An occasional meal with wheat protein as its sole protein source is not the end of the world, but you want to consume mainly quality complete protein from sources like those at the top of the list. 2 ) CARB S Carbohydrates vary along two basic dimensions; the glycemic index and micronutrient density. Higher glycemic index carbs digest more rapidly and spike insulin higher, while low glycemic index carbs digest slowly and spike insulin much less. Potential effects of carb consumption are revealed in body composition and performance. Performance is better enhanced by higher glycemic carbs, especially when they are consumed during and post workout to provide energy, anti-catabolic drive (prevention of muscle loss), and faster glycogen repletion (replacement of energy stores in muscle). Although the data on this subject is less clear, low glycemic carbs usually have high vitamin, mineral, and fiber density, which may have a small benefit to body composition. Thus, our recommendation is to consume higher GI carbs (like sugary cereal and Gatorade) during and post-training, but stick to high micronutrient density lower GI carbs (like sweet potatoes and whole grain bread) for most other meal times. If you are unsure, there are online resources for looking up glycemic indices. Use sugar as your reference for high GI and whole wheat bread or brown rice as your reference for lower GI carbohydrate sources. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 33 3 ) FAT S Fats come in several varieties important to body composition and health. • Monounsaturated Fats tend to have a large positive impact on body composition • Polyunsaturated Fats have a pretty neutral effect on body composition • Conventional Saturated Fats can have a negative effect on body composition if over-eaten, but need to be consumed in minimum quantities to provide important hormonal and cell machinery support for body composition and performance adaptations • Healthy Saturated Fats (grass fed animal fats and coconut oils, for example) may be a healthy fat, but the research is still unclear at this time • Trans-Saturated Fats are generally unhealthy and have a negative effect on body composition In Figure 3 below, we’ve given a rough recommendation table for various forms of fat consumption. FA T T Y P E RECOMMENDED INTAKE Monounsa tura ted 60% Polyunsa tura ted 15% Hea lthy S a tura ted 15% Conventiona l S a tura ted 10% Trans 0% EXAMPLE FOOD Avocado, nu ts and their bu tter s , olive oi l Vegeta ble oi ls Coconu t/macadamia nu t oi ls , grass fed anima l fa ts Fa ts from conventiona lly far med bacon, eggs , cheeses , bu tter s S tore -bought ba ked goods , mos t fas t food Figure 3. Fat Composition Intake Recommendations Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 34 In summary, eating mostly animal protein products, mostly low GI and micronutrient-dense carbs (except maybe during and right after workouts) and a diet rich in monounsaturated fats may slightly help to promote body composition and performance. Percentages in the above table are listed in terms of percent of your total fat intake, not of total calorie intake…in case you got excited about a diet of 60% avocados and almond butter. Next, we will take a look at which supplements might work to give us our last 5% boost to physical appearance and performance enhancement. Supplements The bad news on supplements is that most of them have no measurable effect on either body composition or performance. That’s right, when you walk into a supplement store, most of the supplements you see on the shelves contain extracts and compounds that are quite simply a waste of money. The good news is that there are a few supplements which, over the course of many years of research, have been shown to have a positive effect on performance and body composition, and we have a quick summary of them right here: 1 ) W H EY P R OT EIN Whey protein is a protein fraction of milk (the other component of milk protein is casein). It digests and absorbs faster than any other known protein and is of the highest quality, making it ideal for consumption when the GI tract can’t work very hard (due to blood being away, in the working muscles) and when amino acids are rapidly needed, exactly the kind of environment seen during and right after training. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 35 2 ) CASEIN P R OT EIN The other fraction of milk protein, Casein, is incredibly slow digesting, capable of releasing a steady stream of amino acids into the blood for up to 7 hours after consumption. For this reason it’s a poor post-workout choice, but a great meal replacement for long durations without food and the most commonly occurring example of such a situation; the pre-bedtime meal. 3 ) C REAT IN E Creatine increases the ability of the phosphagen system to provide high-intensity energy for exercise. Essentially, it gives you several seconds worth of high-rate ATP with which to smash through each set during workouts. Not only this, but creatine also builds muscle over the long term. 5g of creatine for 2 months on and then one month off will do the trick for most people, but expect a 5lb temporary water weight gain within a week of starting the supplement. Don’t worry, at the end of the 2 months that weight comes right back off, but you keep the muscle. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 36 The creatine type with the most research behind it is Creatine Monohydrate, so that’s the one we can best recommend. As a bonus, in simple powder form, it also tends to be the cheapest option available. 4 ) GLYC EMIC CARB P OW D E R S By spiking insulin and taking very little digestion time to appear in the blood, glycemic carb powders such as Gatorade, Powerade, and Tang are a great combo for post-workout glycogen repletion, especially when training twice per day. The expensive stuff is probably not any better than plain old store-bought Gatorade powder, and if it is, it’s just by the tiniest bit. 5 ) ST IMUL A N T S Stimulants, the most common of which is caffeine, offer several distinct advantages to the athlete • Stimulants reduce appetite and thus make hypocaloric dieting easier • Stimulants increase workout energy, pain tolerance, and endurance, even in hypocaloric conditions • Stimulants can enhance your focus and attention span, which can help you both at work and in training, especially when calories are low By using stimulants responsibly (starting with low doses, ramping up the doses slowly, taking several weeks out of every several months to reduce or cease stimulant intake to re-establish a sensitivity), your regular training and especially your training on a hypocaloric fat loss diet can be impressively enhanced. Do these 5 supplements work? Almost certainly. Do they have a big impact on results? Almost certainly not. Even if we combine the effects of all of these supplements at the same time, the total improvement to body composition and health sums up to just around 5% of the total effect that diet can bring. In a word; focus on your food intake way before you spend time concerned about which supplements to take. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 37 Micronutrients Before we round out the chapter on basic nutrition, we must briefly discuss an aspect of nutrition that not only has pertinence in terms of performance (especially if very badly approached), but on general health as well. While macronutrients get much of the attention, micronutrients are actually of critical importance. While micronutrients do not really boost performance directly, they support it at a deep level by promoting general health. Let’s zoom in and talk specifics about the four micronutrients: water, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. 1 ) WAT ER Proper hydration results in part from eating moist foods (such as fruit), but also from drinking water and other beverages. Generally speaking, for a high likelihood of health and performance maximization, 5 ounces of fluid for every 100 calories of food consumed seems to be a good starting value. So if you are consuming around 2000 calories per day, you should be shooting for around 100oz of water intake per day, not including food. This value might seem intimidating, but it’s really just over three 32oz Gatorade bottles of water for the whole day. Not too crazy if you think about it. While this amount of water is a baseline, some populations may need more water, including women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, exercising or eating a high protein diet. Some readers will be in several of these categories at once, so please take note! How do you know you are hydrated? If you urinate four or more times per day and your urine is either off-yellow or clear consistently, you are likely sufficiently hydrated. If you notice less frequent urination or darker urine for a day or two on end, upping your fluid intake is a good first step. It also turns out that there can be ‘too much of a good thing’. If you overdo it Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 38 with the water, an unlikely but possible result can be a dangerous condition called hyponatremia. As its Latin name implies, hyponatremia is a condition of abnormally low sodium in the bloodstream and body fluids, usually resulting from over dilution caused by too much water being taken in without adequate sodium or too much sodium being lost and not replaced. Because sodium is a critically important ion for nearly all forms of muscle contraction and nerve signal transduction, dangerously low levels of it are very serious. Acute bouts of hyponatremia can result in the death of brain tissue and may (and have in rare cases) result in brain damage, coma, or death. Post-menopausal women are one of the highest risk groups for brain damage as a result of acute hyponatremia. The two predominant causes of hyponatremia are rapid and excessive water intake without any electrolytes or food added (such as in water-drinking challenges as a part of hazing rituals) and rapid water-only rehydration after intense dehydration that lead to lots of sodium loss in the sweat. Weight cutting and hard training in hot environments are typical causes of hyponatremia in the fitness world. The great news is that preventing hyponatremia is not terribly difficult. Consuming electrolytes (Powerade Zero or electrolyte mini-squirt bottles added to water) along with water, during and after intense exercise is a great start. While basically any sports drink would also work, many sports drinks add extra calories you may or may not want to consume in your diet at the moment. Additionally, rehydrating more slowly always helps, with 7-10 ounces being consumed every 10-20 minutes instead of gallons at a time. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 39 On the opposite end of the spectrum is dehydration. Transient dehydration can occur during exercise; the GI tract can only absorb around a quart (32oz) of water per hour, and some very tough or hot exercise can exceed those uptakes, sometimes by double. In fact, one of the reasons behind the fatigue of hard exercise is the dehydration itself. Light dehydration during exercise can lead to a 1-2% temporary loss in body weight, a small thirst response, and decline in mental focus and physical output via mild fatigue. Moderate dehydration can cause bodyweight losses of 2-4% at the end of exercise, dry mouth with a powerful thirst response, headache and dizziness or lightheadedness. On the higher end of moderate dehydration (around 5%), cramping will become a noticeable symptom for many people and athletic ability will be greatly reduced. Severe dehydration occurs at 7-10% bodyweight loss, a situation which, in the fitness world, almost exclusively happens during intentional weight cutting to make a low weight class. Symptoms may include hallucinations, extreme thirst, low blood pressure and rapid heartbeat and breathing. Possible risks include heat stroke, shock, coma and death. To say that we do not recommend cutting this much for a meet is an understatement. While hydrating for activity varies greatly with the activity intensity and duration and the temperature (both outdoor and related to how much clothing you are wearing), some general recommendations are helpful. Consuming 2 cups of fluid 2-3 hours before exercise, a cup right before exercise, and a cup for every 2030 minutes of activity can be a great start. After activity, consume fluids slowly but steadily until voluminous and clear urination returns, which often means consuming around 1.5x the water weight you lost during the activity. And remember, if you’ve been dehydrated to a moderate or greater extent, rehydrate with electrolytes added, not just plain water. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 40 2 ) V ITAMIN S Vitamins are important for both health and athletic performance and come in two basic types; water soluble and fat soluble. Water soluble vitamins are readily absorbed from the GI tract and are not stored long term in the body, with excess intakes being excreted in urine or fecal matter. Fat soluble vitamins must be bound to fat to be absorbed from the GI tract, and thus often have to be consumed with a food source. Fat soluble vitamins can be stored for longer periods of time in the body’s adipose tissues, and prolonged very low fat diets may cause fat soluble vitamin deficiencies. Vitamins A, D, E and K are fat soluble and the rest are water soluble. Vitamin A, most B vitamins, vitamin C and vitamin K are found largely in fruits and vegetables, which is part of the reason why consuming fruits and veggies is so important. In addition, fruits and vegetables contain phytochemicals, which unlike vitamins, are not essential for life, but have small positive effects on health. The trick with most phytochemicals is that you can only get them by eating real fruits and veggies, not through most supplements. Vitamins B12, D, and A are available most abundantly in animal sources such as meat, fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy. In fact, vitamin B12 is only found in animal based sources, so vegan and vegetarian fitness enthusiasts likely need to supplement with B12. Vitamin E is most abundant in seeds and oils, such as many of the monounsaturated fat sources recommended earlier. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 41 Still other vitamins, such as K and D, are made in the human body, by gut bacteria and by the skin, respectively. Is vitamin supplementation a must? Surely, a multivitamin tab once a day is a good “just in case” policy to round out intake, but nothing beats a healthy diet. 6-8 servings of fruits and veggies per day, especially varied ones of different colors can go a long way in ensuring needed vitamin intake. In addition to consuming whole grains, enriched cereals, lean meats and healthy fats, vitamin supplementation is likely not needed. In the case of dieting for weight loss, vitamin supplementation however is likely a good idea, just in case your hypocaloric diet results in too big a reduction in vitamin intake. 3 ) MIN ERAL S Minerals come in many varieties, an important one of which is electrolytes. Sodium, chloride, magnesium, potassium, and calcium are important to the fluid balance of the body and to the proper functioning of all muscles and nerves. Most people get enough sodium and chloride by a long shot from table salt intake, and magnesium deficiency is rare, but potassium and calcium are often underconsumed, especially by women. While potassium can be found in most fruits and vegetables, and especially in potatoes, dairy products are the best source of calcium, with Vitamin D being critical to the latter’s absorption and thus utilization in bone growth and repair. Adequate calcium, vitamin D, phosphorous and protein are required in order to slow the inevitable loss of bone mineral density after age 30. 1200mg of calcium and 600mg of Vitamin D per day is the goal for most women, with supplementation being helpful in many cases. While iron is not an electrolyte, it is the central and critical atom of hemoglobin, the molecule in red blood cells that transports oxygen to the cells and carbon dioxide back out through the lungs. If insufficient intakes of iron occur, a lack of functioning red blood cells can result, which is termed Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA). IDA impairs oxygen transport to working muscles and will thus greatly interfere with both training and recovery. In order to prevent or reverse such Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 42 anemia, iron should be taken in from mostly animal protein sources, with plant sources containing an inferiorly absorbed form of iron. Interestingly, the presence of Vitamin C in a meal enhances iron absorption, which supports the practice of eating fruits and/or veggies with meat-containing meals. Due to menstruation and the iron loss of that process, women of childbearing age may need an iron supplement in some cases. 4 ) F IB ER Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that usually provides no calories or trace calories for humans because our digestive enzymes cannot break the bonds that connect the sugar molecules of fiber together. However, beneficial bacteria in the gut can ferment fiber and use it for energy, which can help promote healthy bowel function for their human symbionts. Fiber comes in two general varieties; soluble and insoluble. Soluble fibers retain water and form gels when in water. They are easily digested by bacteria in the colon and they can bind to cholesterol and glucose in the small intestine, lowering the absorption of both. Their inclusion in food usually adds a pleasing consistency to the food. Insoluble fibers are the molecules that used to form the supporting structure of plants before they became a part of your next meal. They largely do not dissolve in water and are not easily fermented by gut bacteria. Included in this category are fibers that retain much of their tough structure after cooking, including bran, strings of celery, and skins of corn kernels. Because such fiber draws fluid into the bowels and because it acts as a kind of scrubber brush to the GI tract as it passes through, insoluble fiber is helpful in aiding digestive system health and effectiveness as well. Fiber has numerous health benefits. It lowers blood cholesterol levels by binding to the cholesterol of bile in the GI tract and passing it along for excretion. It can help control diabetes by slowing the release of glucose from the small intestine Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 43 into the blood, and it has even been shown to reduce heart disease risk. By softening stool and drawing fluid into the GI tract, fiber can decrease the risk of GI conditions including diverticulitis, constipation, and hemorrhoids. By pulling along the contents of the GI tract faster, fiber intake can reduce exposure to carcinogens and may reduce the risk of certain cancers, including those of the colon. Another big benefit of fiber is its role in weight management. In a process that will be greatly detailed in a later chapter, fiber can add a significant volume to food. In addition to drawing even more fluid into the GI tract for even more volume, this effect can stretch the walls of the GI tract and lead to enhanced feelings of fullness. Because fiber has at most trace calories, this feeling will ease hypocaloric dieting without adding a bunch of calories! With between 25 and 35 grams of fiber per day, most females will be well on their way to the multiple health and functional benefits of fiber consumption. References P OSIT IO N STAT EMEN TS A ND G U I D E LI NE S • Sport Nutrition. An Introduction to Energy Production and Performance. 2nd ed. • National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for Athletes. • Practical Sports Nutrition • Advanced Sports Nutrition • Nutrition: Concepts and Controversies. 13ed. • NSCA’s Guide to Sport and Exercise Nutrition. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 44 SPEC IA L C O N D IT IO N S • Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions. Iron deficiency anemia. • Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions. Hyponatremia. • Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions. Dehydration. CALO RIE BA L AN C E • ACSM position stand on nutrition and athletic performance • Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise • What is the required energy deficit per unit of weight loss • Nutritional guidelines for strength sports: sprinting, weightlifting, throwing events, and bodybuilding M AC R O N UT RIEN T S • A critical examination of dietary protein requirements, benefits, and excesses in athletes • Dietary protein requirements and adaptive advantages in athletes • Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation • Effect of two different weight loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes • Effect of dietary macronutrient composition on AMPK and SIRT1 expression and activity in human skeletal muscle • Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery • Guidelines for daily carbohydrate intake: do athletes achieve them ? • Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 45 NUT RIEN T T IMIN G • Nutrient Timing: The future of Sports Nutrition • Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window? • International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: meal frequency • Meal Frequency and Energy Balance • International Society of Sports Nutrition Position stand: nutrient timing • Association between eating frequency, weight, and health • Sports nutrition needs: before, during, and after exercise • The use of carbohydrates during exercise as an ergogenic aid FOOD C O MP O SIT IO N • The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score • Glycaemic index, glycaemic load and exercise performance • Glycemic index in sport nutrition • Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular health: research completed? • Trans fatty acids and weight gain • Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease controversy SUP P L EMEN T S • Effect if whey isolate on strength, body composition, and muscle hypertrophy during resistance training • Effects of whey protein supplements on metabolism: evidence from human intervention studies • Fluid and carbohydrate replacement during intermittent exercise • In sickness and in health: the widespread application of creatine supplementation • Creatine supplementation and athletic performance Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 46 • International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: creatine supplementation and exercise • Efficacy and safety of ingredients found in preworkout supplements • Nutritional supplements and ergogenic aids • Dietary supplements for improving body composition and reducing body weight: where is the evidence? Summary & Implications The effect of the diet principles on body composition and performance can be summed up simply as follows: • Calorie Balance: 50% • Macros: 30% • Timing: 10% • Food Composition: 5% • Supplements: 5% If we are just starting out in our diet journey, where do we first make changes? If we have a limited time to dedicate to the dieting process, which is often the case, what do we focus on most? Well, the priorities make these answers very straightforward. Every attempt at dieting should begin with calorie manipulation. That is by far the biggest and most impactful piece of the puzzle. No matter what the situation; vacation, airports, conferences, stressful exams or deadlines, a specific calorie allowance can be met by simply controlling food intake. With a little more breathing room and in most situations, macros can be at least somewhat approximated and tended to next. Trying to eat some lean proteins and carbs with every meal is not the most difficult thing in the world, and once you get your calories correct, just these two manipulations will pay off hugely. When you have Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 47 Every attempt at dieting should begin with calorie manipulation. the first two priorities taken care of, you can move on to timing, composition, and supplements at your leisure. It might even be the case that your first few rounds of dieting, you get some practice fulfilling the first two principles. Then once you feel comfortable with these and find it’s less work to think about them, you will have the mental capacity and time to start applying the other three principles. Of course if you were not aware of the priorities, you could get this totally backwards. For example, every year, thousands of male college students (and probably a growing number of females as well) living in dorms try to gain muscle and fail. They buy supplements galore, but don’t eat either enough food to be hypercaloric, or enough protein to support muscle growth. They simply do not know about the priorities. They spend money on buying the latest creatine formula, but fail to take advantage of the calories provided in the all-you-can-eat cafeteria! Having read this chapter, you can now avoid this kind of mistake; we have discussed the main priorities to tend to when dieting to lose or gain weight. Apply them in the described order and you will achieve results. Now that we have covered the basics of dieting for body composition and performance, it is time to zoom in on the details of dieting to lose fat. Chapter One F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 49 P. 5 0 02 Dieting Procedures For Fat Loss When setting up a strategy for fat loss, there are a series of steps in the diet design process. We will walk through the steps of constructing an effective fat loss diet based on the principles we learned in Chapter 1. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 50 Chapter Two When setting up a strategy for fat loss, there are essentially seven steps in the diet design process. Below is a list of these steps, in general terms. In this chapter, we go into the detail behind each step, one at a time.. 1. Establish a base intake for your stable bodyweight 2. Generate a caloric deficit to lose weight at the right pace 3. Calculate the amounts of proteins, carbs, and fats you will need to take in to meet those calories, and follow the rules of timing, food composition, and supplements 4. Track bodyweight to make sure progress is on the right track 5. Adjust calorie and macro intake as needed in order to keep bodyweight loss on track 6. Plan your diet duration for best results 7. Take time to re-establish positive and stable psychological and physiological states after dieting - before embarking on another fat loss diet P 51 Let’s take a close look at each of these steps and establish our recommendations in terms of executing them in the best way possible. This will give you a blueprint for planning your own successful fat loss diet. 1 ) ESTAB L ISH A BASE I NTA K E F O R YO U R S TA B LE B O DY WEI G HT In Chapter 1, we determined that the most important factor in fat loss dieting is the creation of a caloric deficit, accomplished by the reduction of calories being taken in per day. Before we can find out how much food to reduce for a fat loss diet, however, we need to determine the number of calories we would need to consume to maintain our current weight. In figure 3 below, we list a starting point of calorie intakes by bodyweight and activity. TRAINING VOUME BODY WEIGHT LIGHT/OFF MODERATE HARD 100lbs 1500 1935 2400 125lbs 1650 2185 2650 150lbs 1850 2435 2900 175lbs 2050 2785 3200 200lbs 2300 3135 3500 225lbs 2550 3585 3950 250lbs 2850 4035 4400 275lbs 3150 4585 4950 300lbs 3550 5135 5500 Figure 4. Estimated Average Caloric Requirements for Maintenance Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 52 It is important to understand two qualities of the above table. First, these numbers were generated from several metabolic equations, and represent averages. Since there is, without question, individual variation, these averages should be used just as starting guides. Taller women will need more calories, while shorter women of the same weight will need fewer. Younger women will need more calories, while older women will need fewer. Those with genetically faster metabolisms will need more calories than those with slower metabolisms. Thus, you can and should absolutely start your baseline maintenance diet with these average values, but they will need some adjusting in most cases, which brings us to the second point. In order to individualize the diet for yourself, you should start with the appropriate average from the table above, and then modify according to how your weight changes as you progress through the diet. If you are gaining weight steadily once you begin following a diet based on one of the above averages, then you need to lower your calorie intake. This should be done via reducing 250-500 daily calories at a time. Once you have made this alteration, track your weight for a week or so and see if that stabilizes weight. When you have found the caloric intake that keeps your weight the same, you have found your base intake for stable body weight. If you are losing, apply the same strategy in reverse, adding rather than subtracting calories. To determine whether you are losing or gaining weight, never go by a single weigh in. Weigh yourself 2-3 times per week, take an average, and then assess changes week to week. The above strategy will allow you to establish a caloric intake across weeks that will keep your weight stable. To perfect this in terms of daily caloric intake – as your caloric needs will vary depending on whether you are sedentary or have a hard work out – you can use Figure 1 from Chapter 1 to help adjust intake according to energy output for all of your different weekly workout and rest days. Now that you have established your baseline intake, it’s time to move onto Step two, generating a caloric deficit. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 53 2) G e nera te a ca l o r ic defici t to l o s e weight a t the r i g h t pace Since the most important ingredient of a fat loss diet is the act of eating less than you burn, creating a caloric deficit is the most critical step of the process. Current data suggests that the most productive middle ground for a caloric deficit is one that results in losses of somewhere between 0.5% and 1.0% of bodyweight per week. This means that for a woman that weighs 150lbs, a very good start for a weekly weight loss goal is somewhere between 0.75lbs and 1.5lbs. It doesn’t sound like much, but a 12 week diet at this rate (even with a middle value of around 1lb per week) will lead to a bodyweight of around 138lbs. A 12 pound loss for a 150 lb woman means a completely different look and performance level a mere 3 months later. P 54 We went over this in Chapter 1, but let’s fine tune it now. • Too small a deficit and we end up having to diet for weeks, if not months longer than necessary. Because dieting to lose fat ranks in fun somewhere between doing yard work and catching darts for a hobby, we don’t want to needlessly prolong the process. • Too large a deficit, and we end up accumulating a ton of fatigue quickly, because we are lacking the nutrients to properly recover from training. This also leads to muscle and performance loss, which nullifies aesthetic and athletic goals alike. Additionally, super fast dieting can be psychologically unsustainable (radical hunger cravings, excessively low daily energy, and so on) and often leads to burnout and rebound. In order to generate such a level of weight loss, we will use the common understanding that a pound of fat is 3500 calories. Now, this is just a very rough estimate and tends to differ quite a bit based on the situation, but because we are just establishing our starting point for dieting, we can afford to make rough calculations. Later we’ll learn how to make much more precise adjustments to individual circumstances and physiologies. If a pound of fat is lost with 3500 calories burned, we can assume that around 500 calories of deficit per day is going to lead to roughly 1lb of weight lost per week, at least at the start of a diet, and in most situations. Thus, for our 150lb example woman (sounds like a superhero… “it’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s Example Woman!”), a 500 calorie deficit is going to generate the 1lb per week weight loss we’re looking for, or at least close. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 55 SO, TO START THE PROCESS OF GENERATING YOUR CALORIC DEFICIT DIET PLAN FOR FAT LOSS a. Choose your percent weight loss. Example: 1.0% per week. b. M ultiply your weight loss percentage by your current bodyweight to estimate weekly weight loss needs. Example: 150lbs x 0.01 = 1.5lb per week. c. M ultiply your weekly weight loss in pounds from b. above by 3500 calories to get the calorie number per week. Example: 1.5lb x 3500 = 5250 calories per week. d. Divide the weekly calorie deficit by 7 to get the average daily deficit. Example: 5250/7 = 750 calorie deficit per day There it is; your daily deficit is calculated. Now, this is the deficit which can and should be generated by a combination of increased activity and decreased food intake. Make sure that if you increase your activity, you follow the guidelines for calories listed in the activity levels (rest day/light day, moderate day, hard day) above. If you do this, you can just subtract your deficit from the higher intake amounts for those more active days, and the result will still be a calculated deficit, not accidentally more or less. Does 750 calories sound like a lot to cut from a 150lb female diet? You bet, but 1.5lbs of weight loss per week is one heck of a pace and the fastest we would recommend. For most beginner dieters, we recommend starting closer to the 0.5% mark, which in this example would be only a 325 calorie per day cut. If you are not used to dieting, this will be a less painful pace and therefore might be more sustainable for newbies. Now that you’re on track to lose weight at the right pace by cutting calories, we’ve gotta make sure those calories are coming from the right macros. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 56 3) Ca l cu l a t e t h e a mount s o f p ro t e i n s , car bs , a n d fa t s t o t a ke i n t o me e t t h o s e ca l or ies , and foll ow t he r u l es o f t i mi n g , fo o d co mp osi tion and s u p p l e me n t s This part starts out super easy; we’re just going to carry over our protein and carb recommendations right from the maintenance phase. Why are we keeping proteins and carbs high at first? If we have a certain number of calories to cut, why not just cut them evenly from all three of the macros? The answer is very straightforward; the three different macros do not have the same effect on body composition and performance. Since protein has the highest positive effect on diet outcomes (it provides building blocks for muscle growth or maintenance), we’re going to keep it high for as long as we can and avoid cutting it for as long as possible. Carbs are a close second to protein in their effect on body Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 57 composition and arguably even more important for performance, so we want to avoid cutting those for as long as we can also (though they would go before protein). Then, where will we cut calories first? While fats are a critical part of the macronutrient intake equation, their beneficial effects can be had with minimal intake levels, even below recommended intake. This means that, to a certain low point (0.3g fat per lb LBM for long term, 0.1g fat per lb LBM for 2 months or less), we can use fats to cut our calories without much of an impact. Yes, the intake of fats helps us upkeep muscle and performance via hormonal and intracellular processes, but as stated, we can cut fats, even to pretty extreme levels for short periods without any detriment to these processes. So fats are the perfect place to start cutting when shooting for our deficit. When beginning our calorie cut, we now know what macros to start with. Let’s use our 150lb example woman who wants to lose at a 1lb per week pace, and use her “moderate” training day as an example. We will assume she is at about 20% body fat, making her lean body mass (LBM) about 120lbs. Base Calories: 2435 Base Protein: 120g (1g of protein multiplied by 120lbs as her LBM) Base Carbs: 180g (1.5g of carbs multiplied by 120lbs as her LBM) Base Fats: 137g (2435 total calories minus 1200 calories from protein and carbs, leaves us with 1235 calories. Divide this by 9 calories per gram of fats= about 137 grams) (Remember from Chapter 1 that fats have about 9 calories per gram.) We know that she needs to drop her calories by about 500 per day if she wants to lose a pound of tissue a week, so our new base calories are 1935 (2435-500). And because we’re going to take all those away from fat, we’re going to leave our protein and carbs the same at first: Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 58 Starting Cut Calories: 1935 Starting Cut Protein: 120g Starting Cut Carbs: 180g Starting Cut Fats: 82g (1935 total calories minus 1200 calories from protein and carbs, divided by 9 calories per gram of fats) So there we have it… dropping only our fats from 137g to 82g reduces our calories by 500 or so and gets us rolling at 1lb of weight loss per week. As metabolism changes (addressed in the next section), we’ll have to drop more calories to stay on track. So do we just keep using fats? Yes, until the following happens: a. There is more than 2 months left of dieting, and you’re down to 0.3g fat per lb LBM. b. There is less than 2 months left of dieting and you’re down to 0.1g fat per lb LBM. In both cases a. and b. above, you can start cutting carbs to increase the calorie deficit. Using our 150lb example female, if she’s down to 1524 calories and has 2.5 months left in her diet and needs to make another reduction, we have to cut carbs. At this point, she’s at only 36 total grams of fat, which is 0.3g of fat per her 120lb LBM, and going any lower would greatly impact muscle retention and performance. By cutting her carbs, we leave the all-important proteins alone and we make sure we’re still getting enough fats to maintain the minimum needed levels for best results given our low calorie conditions. Is it ideal to cut carbs at this point? Of course not. In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have to make any cuts whatsoever and we could still make crazy fat loss possible. But since the calories have to be cut from somewhere, once the fats are at their bottom limit, the carbs have to start being cut. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 59 Do proteins ever get cut? That is possible, but for our example woman to run completely out of carbs through calorie cuts, she’d have to be eating 120g of protein and (let’s say it’s within 2 months of the end of a diet and we can drop to 0.1g fats per lb LBM) 12g of fats. That comes out to a total daily calorie amount of 588. Unless you’re a couple weeks out from a super-competitive physique show and you need that last little bit of out-of-this-world conditioning, going that low in calories is neither needed nor recommended in almost any case. Thus, the takehome message about protein cuts is; if you’ve dieted so far that you need them, you should almost certainly hire a highly qualified diet coach to guide you that last step of the way. If you’re eating 600 calories per day or less without a clear, proximal and exotic goal of an extreme physique or weight for some kind of important competition, you’re almost certainly doing something wrong in your dieting approach. APP LY IN G T H E L AST T HR E E P R I NC I P LE S F R O M C HA P TE R 1 When programming your cutting diet, don’t forget sensible timing. Don’t go longer than about 5 hours without eating, and make sure you have a post (or even intra/post) workout shake after your weight training sessions. Eat most of your carbs around training and most of your fats far away from it. Have a relatively even amount of protein in each meal. While you’re cutting all of these nutrients slowly but surely, don’t forget to keep in mind the food composition rules from the 4th principle of scientific dieting. Eat mostly whole foods, with lean animal proteins, whole grains, fruits, veggies, and healthy monounsaturated fats for most of your meals. At night, try to consume a casein or milk-protein source of protein to keep your blood levels of amino acids up while you sleep. This prevents muscle loss during sleep (which is essentially a prolonged fast). Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 60 If you’re going to take supplements, do so consistently and intelligently. Slowly ramp up caffeine intake as the diet progresses… don’t just start with the kitchen sink! 4) Tra ck you r b o dywe i g h t t o ma ke s u re progress is on t he r i g ht t rack So our example woman cut her calories by 500 per day with the intention of losing about a pound of tissue per week, of which most should hopefully be fat if she does everything else correctly, including training hard. But how does she know she’s’ on track? Let’s say she wanted to lose 12lbs of fat within 3 months… how does she know if the diet is working and if she needs adjustment? Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 61 The very simple answer is that she has to track her bodyweight. We have to remember that our calculations of calories being taken in and calories being burned are just estimates. Metabolisms differ, portion sizes differ even with the best intentions, and actual daily calories burned differ as well. The only sure way to know if weight is changing is to measure. HOW OFTEN SHOULD BODYWEIGHT MEASUREMENT OCCUR? A COUPLE OF CONSIDERATIONS • Bodyweight fluctuations can normally fall within 2% of actual tissue weight, both up and down. Thus, even aside from menstrual cycle fluctuations, a 150lb female may weigh between 148lbs and 152lbs on any given day without actually gaining or losing any tissue, just water weight. Eating more or less carbs or fats in the day before a weigh-in can be a big contributor to this phenomenon. • Given that weight tends to fluctuate, we can’t just measure bodyweight once per week and use that to decide our next week’s diet changes. If you eat some Chinese food (within your macros) the night before a weigh-in, you could be up 2lbs over your actual tissue weight, causing you to make the decision to cut calories further than you need to, and risk muscle loss for no reason. If you are a bit dehydrated or eat a low-carb and low salt diet the day before, you could be tricked into thinking all is well with an artificially low weigh-in the next day, prompting a week of slow or no fat loss progress because you didn’t make the cuts you should have. • Measuring bodyweight once a day is just fine, but catches mostly water fluctuations in its daily changes. It gives us a needless level of precision, and likely anxiety, while coming at the cost of high dedication. Weighing in daily means having to drag your scale around on weekend trips and other such inconveniences. Taking the above considerations into account, the best approach to weight tracking seems to be to take a bodyweight measurement between two and three times per week. To be consistent, first thing in the morning is a good time to take weight, as water and food weight is largely obviated, or at least somewhat Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 62 normalized. Also remember to weigh in either naked or with the same amount of clothing on each time. It’s also a good idea to use the same scale, as variations in scale accuracy may exist. Lower your calories by cutting fats and weigh yourself 2-3 times per week, and you’re well on your way. Usually this will result in a couple of weeks of wellpaced weight loss. Now, what is the procedure for getting weight back on track if it doesn’t cooperate after a few weeks? 5) Ad j u s t ca l o r i e a n d ma cro i nt a ke t o keep b od y we i g ht l o s s o n t ra ck Once you have your weight loss moving at the desired pace, it is likely that after a few weeks, losses will slow and you will need to adjust. Below are instructions for how to deal with this as well as for other scenarios you might face earlier in the diet process, when first establishing your cut. As you start cutting, there are three possible scenarios: a. You are losing weight at approximately the rate you want. b. You are losing weight too quickly. c.You are either losing weight too slowly for your planned rate of loss, not losing any weight, or gaining weight. Let’s take a look at each of these scenarios and see what, if any, adjustments need to be made. A. O N - T RAC K W EIGH T LO S S This is the easiest option by far, and requires no effort whatsoever on the part of the dieter, other than of course to continue to execute the plan as written. As easy as this sounds on paper, there are two common pitfalls in this situation: Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 63 • The temptation to try to change the plan to get even faster results. Because you should already be on track to make good progress, this move is much more likely to throw off sustainability than it is to help. If it’s a calculated decision and it is made logically and in advance, that’s completely fine. It’s the emotional temptation to always seek more out of the same limited resources that carries problems. Pick a good plan and stick to it. • Related to the first pitfall, the temptation to want to change the diet just for the sake of changing the diet, even though the results are already the desired ones. In our consulting work at Renaissance Periodization, very occasionally some clients will go weeks without needing any update to their diets. They just lose and lose and lose weight at a steady pace while sticking to the original plan; an almost ideal situation! A tiny minority of these clients, having been promised an interactive and continuously updated diet, will become quite upset that their diet has not been updated, regardless of their progress! It’s important to avoid the thinking that changing a diet is good in and of itself… it’s only a good thing when it’s needed, not when all is on track! If you’re losing at the right pace, smile and enjoy the temporary serendipity of the universe… this state of affairs usually doesn’t last long! B.) RAP ID W EIGH T LO S S At first glance, this situation sounds like a good thing, but muscle and performance will be negatively impacted if weight loss proceeds much faster than 1% per week, so we’ll want to have strategies to deal with this possibility. If you’re still chopping away at your fats and are at a full complement of proteins and carbs, adding fats back into the diet until weight loss returns to an acceptable pace is likely the best idea. If your weight begins to fall too quickly when your carbs have already been cut, then returning more carbs to the intake is the first step in normalizing the pace. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 64 Add fats if you haven’t cut carbs yet, and add carbs if you have cut carbs already, but how many calories are we adding? That can depend on the rate of weight loss, but generally, adding around 250 calories per day to the diet will be a good start. If you’re losing MUCH faster than 1% per week (3% or so, consistently), then adding 500 calories might need to occur. But hey, great problems to have! Adding 250 calories per day at a time for a week or so is probably the best way to begin slowing rapid weight loss. For example, if you are eating 2000 calories a day and losing too quickly, switch to 2250 calories per day. Eat that for a week and if you’re still losing too fast, go to 2500 per week and see how it goes. C. SLOW O R N O W EIG HT LO S S The not-so-great problem to have is that of slow weight loss, no weight loss, or even weight gain. In this situation, you want to follow the opposite advice of situation b. and cut calories once a week by 250 per day in order to get weight to move in the right direction and at the right pace. Even with the best designed diet, and even if you make no changes to it, weight loss will eventually begin to slow from your initial pace for the following reasons: • The longer you stay in a hypocaloric diet, the more your metabolism will slow down. This means that on your original cut plan the rate of loss will get slower and slower, eventually stopping completely. • As your metabolism slows, you’ll unconsciously begin to move and fidget less in your daily life, causing a reduction of total calories burned. • The more weight you lose, the less tissue you have. The less tissue you have, the lower your metabolic rate will be, independent of hypocaloric effects. You’re now simply smaller and it takes less food to keep all of your body functions operating. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 65 In most any situation, as you continue to lose weight on the diet, your results will inevitably slow. Each time this happens, you’ll need to update the plan to re-create a deficit so as to speed things back up into the desired range for fat loss. You can do this through a combination of decreasing intake or increasing expenditure (traditionally done through cardio exercise), or a combination of both. In most of the examples, we’ll be assuming that you’re already training hard and that your diet is the primary place for manipulation. In this case, if your last week didn’t lead to the weight loss you had planned, lower your calorie intake by dropping 250 calories worth of fats (and that many worth of carbs if you can’t spare any more fats). By following this procedure, you’ll be assured of continual weight loss for the duration of the diet. Speaking of duration, just how long should a diet be, exactly? 6) Pl a n you r di e t dura t i o n fo r be s t re su lts There are 3 simple rules that you can apply sequentially in order to determine your diet duration: a. Create a weight loss goal. b.Apply a maximum pace limit of 1% weight loss per week (with 0.5%-0.75% usually being more sustainable). c.Diet for no longer than 12 weeks at a time without a break to re-set your metabolism. LET ’S EX A MIN E 2 EX A M P LE S C E NA R I O S Woman X wants to lose 10lbs by her next CrossFit competition. The competition is two months away. She weighs 160lbs. She’s got 8 weeks and 10lbs to lose, which gives her a minimum weight loss of 1.25lbs per week. Her maximum allowable pace is 1.6lbs per week, so her goal is completely realistic and attainable within the 2 months she has allotted. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 66 Woman Y wants to lose 30lbs and she doesn’t quite care when, she just wants the weight off! She currently weighs 180lbs. If she diets for the maximum duration of 12 weeks, she’s limited to dieting at around 1.8lbs per week at a max pace. This means that 12 weeks of diet at the fastest pace will yield her just over 21lbs of weight loss. Woman Y must, in her case, take a diet break to re-set her metabolism and come back and lose the remaining 9lbs in another stretch of hypocaloric dieting. Just 9 pounds away and we’re cutting the diet short? Seems annoying and mildly heartbreaking…the finish line is just in sight! Why the need to pause the diet and come back later? Let’s take a look in the next section. 7.) R e - es t a b l i s h i n g P s ych o l o g i ca l a nd P hy si o l o g i ca l S t a t e s Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 67 After a single stretch of dieting and before the next one, the dieter is best served by taking a period of time to re-set her metabolism and psychology. Why the need for this approach? Prolonged (especially 12 weeks or more) hypocaloric dieting has the following effects on the physiology and psychology of the dieter: a. Down-regulation of metabolism via thyroid function b. Increase of general fatigue via high workloads and low calories c.Increase of AMPk (an enzyme involved in a cellular energy homeostasis) activation via high workloads and low calories d. Retention of set point at historically high body weight values e. Increased hunger and desire for palatable foods f. Decreased motivation via overwork and monotony Let’s take a look at each one of these effects and explore what sorts of constraints they place on the duration of a diet. A. D OW N - REGUL AT IO N O F M E TA B O LI S M VI A THY R O I D FU N CT I O N Long periods (weeks) of strict hypocaloric conditions tend to lead to a decline in thyroid hormone secretion. To be sure, thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) are still being secreted, just not at as high a level. One of the main functions of thyroid hormones is to set the base metabolic rate of every cell in the human body. Generally, the more thyroid hormone there is in the blood, the higher the metabolic rate will be. Because thyroid hormone production is lowered during the fat loss dieting process, a predictable decline in metabolism (and feelings of lethargy and a higher likelihood of being and/or feeling cold) is expected. Eating a balanced diet and getting a full complement of vitamins and minerals is a good way to ensure that thyroid activity stays as high as it can; the biggest effector of thyroid hormone secretion is the total calorie level of the diet. Assuming we’re already controlling calories properly (not dropping them needlessly low when our weight is falling on track anyway), we can’t really manipulate this variable. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 68 So other than just dieting properly, we can’t do a ton about thyroid hormone secretion during a fat loss phase and we’re gonna have to fix the imbalance after the diet ends. Like every single one of the factors in this list, the metabolic drop due to thyroid hormone reduction is a big factor in terms of the unsustainability of continuous hypocaloric dieting. If a diet is run far too long, thyroid activity can drop so low that metabolism becomes significantly reduced. This makes losing weight much more miserable because you would have to drop calories even lower to compensate and because you would feel increasingly less energetic due to the thyroid reduction itself. Not a state of affairs you want if long-term success is your goal. A final important reason to avoid letting thyroid activity drop too far is that due to the greatly lowered metabolism after dieting, even a previously normal caloric intake (pre-diet) will lead to rapid weight gain; very bad news, especially when we’re looking for long term success. B. IN C REASE O F GENE R A L FATI G U E VI A HI G H WO R K LOA D S AND LOW CALO RIES When you’re training hard, you deplete fuel stores and suffer some small (mostly microscopic) wear and tear. With proper recovery strategies and a good grasp on training volume, this fatigue can be healed and recovered on time. But with a hypocaloric diet, we take away one of the most powerful weapons with which Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 69 to fight fatigue; high calories. We also start to sleep a bit less or not as well due to several factors like higher levels of hunger, so there goes another super-powerful recovery modality. Add into the mix the high volume of weight training and cardio that many tough fat loss phases include, and we’re setting up the perfect storm for continual fatigue accumulation. By training smart, eating properly and using the best recovery modalities available, we can retard the fatigue accumulation process to a great extent, but we cannot stop it. As calories drop and a diet continues on from weeks to months, fatigue will eventually accumulate to unsustainable levels. This high level of fatigue increases the likelihood of poor technique acquisition and expression in sport, poor physical performance (strength, endurance, speed, and so on), muscle loss, and possibly even injury. At some point, fatigue must be brought down to low levels so that hard training can resume without being counterproductive or risky, and that means the diet has to return to at least isocaloric for some time. An important point to remember is that fatigue reduction while in a hypocaloric state is always a half-measure. It can buy you some time, but the amount of time it buys lessens the longer the diet runs. At some point you’ll need more time to recover than you need to train, and any attempt at continuing to make progress past that point is a fool’s errand. C. IN C REA SE O F A MP K AC TI VATI O N VI A HI G H WO R K LOAD S AND LOW CALO RIES As fatigue accumulates, one of the chemical processes that both detects fatigue and contributes to it is AMPk. A chemical messenger pathway in the cell (and, for our interests, in muscle cells, specifically), AMPk or Adenosine Monophosphate Kinase is an energy regulator. When calories are high, carbs are high, and activity is relatively low (especially endurance activity like cardio), AMPk activity is quite low. However, as calories and carbs drop while training volume and especially endurance activity rise, AMPk becomes much more active. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 70 What does AMPk do? Oh not much, it just signals muscle catabolism (breakdown of muscle tissue) to occur, reduces muscle growth, and converts muscle fibers to be more slow twitch, making them smaller, less explosive, and weaker. Diet for long enough, and pretty soon AMPk activity is dominant. Muscle loss and rapid declines in power and strength performance are sure to occur with increasing magnitude as the diet goes on. Without a rise in calories and carbs and a reduction in training volume, AMPk activity will continue to be elevated, thus presenting serious problems for almost any athlete and fitness enthusiast. S e t t i n g Bo d y wei g h t s Ove r Ti me Figure 5: Set Point Bodyweights over Time Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 71 D. RET EN T IO N O F SET P O I NT AT HI S TO R I CA LLY HI G H BODY WEI G HT VALU ES The human body has a very impressive set of drives to keep it in homeostasis; a stable internal environment. One facet of that stability is the stability of bodyweight. When bodyweight rises or falls, various adjustments are made in order to re-normalize it. Scientists have called this maintenance of weight homeostasis the “set point theory,” and it is quite well supported in the literature. Spending several months or more at any bodyweight seems to lead your physiology to recognize all of that body mass as “its own.” In other words, for lack of a better description, the body ‘wants’ to stay at that weight. Thus, if any of that mass is lost, physiological responses kick in to bring it back. If any gains occur, physiological responses kick in to remove them. The effect of this for fat loss is very straightforward; the more weight you lose, the more the body tries to pull you back up to that old weight. If you’ve gone from 165lbs to 150lbs in 12 weeks, your body will try to pull your weight back up to your set point of 165lbs via various mechanisms including metabolic slowing and hunger level increases. So anytime you lose weight, your body wants to gain it back! Bad news! On the bright side, set points do not function on infinite historical memory. They seem to mostly be a factor of how much you weighed in the past several months. So if you lost 15 lbs to weigh150 lbs, and you carefully maintain that 150 lbs for a few months, then your physiology begins to establish a new set point at 150 pounds or so. After several months at most any new weight, your body now responds as if that’s supposed to be your weight, and will help you stabilize at that new weight instead of dragging you back up to an old weight. The implication here is twofold: Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 72 • Simply returning to unrestricted “normal” eating right after a fat loss diet is a bad idea. Your body’s set point is still up there in the old bodyweight range and your weight has a high chance of floating back up if you aren’t very careful to maintain for a few months. • Taking several months to make sure to stay at your new low bodyweight is a very good idea after a fat loss phase. Once you spend several months at the new weight, your body’s drive to move you back up to the old weight will have diminished hugely, and staying at your new weight while eating “normally” becomes much easier. E. IN C REA SE IN H UN G E R LE VE LS A ND D E S I R E F O R PA L ATAB LE F O O D S The human body has a host of mechanisms to keep you at your set point or return you there once you’ve strayed away. Various physiological adjustments are made (completely outside of your conscious control) to “help you” re-gain lost weight. One of the most powerful of these adjustments is the elevation of hunger levels as weight loss proceeds. The more weight you lose in one continuous streak, the more hunger is upregulated. Not only is hunger upregulated, but hunger for super high calorie and tasty foods (pizza, ice cream, burgers, and so on) is upregulated the most. Why these foods? Because they give you the most caloric bang for the buck, and when your body is on a mission to get back up to a higher set point weight, it is very good at choosing to make you crave the foods that will do this the fastest. Most people who diet end up gaining the weight back, and the hunger factor is a huge part of the reason why. This hunger for tasty foods can present a big problem to dieters interested in fat loss. We’ll definitely need to be aware of this effect if we’re to devise an effective long-term plan to reduce body and fat mass. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 73 F. D EC REA SED MOT IVATI O N VI A OVE R WO R K A ND M O N OTO N Y With high work outputs and hypocaloric conditions, fat loss phases are very fatiguing. In addition, the lack of high volumes of flavorful foods combined with the consistent need to train often leads to quite a bit of monotony. The combination of fatigue and monotony has an incrementally more negative effect on motivation. This effect gets increasingly powerful as a diet wears on. Several months is well tolerated by most people, but more than 3-4 months at a time leads to considerable motivation losses for many, and begins to increase the chances of skipped workouts, cheat meals and even total program stoppage. Alright, so that’s a lot of pretty bad news. The good news is that taking some time to eat at maintenance (neither gaining nor losing weight) reverses all of these effects and allows the dieter to come back later and continue to lose more weight, if desired or needed. After 3 months of dieting, you’ll start your maintenance phase. The purpose of this phase is to re-set every single one of the problems encountered in the discussion above; from metabolism slowdown to hunger cravings and set point lag. SOME GUIDELINES FOR DESIGNING A MAINTENANCE PHASE a. Adding in initial calories b. Preparing for an initial bloat rebound c. Choosing the duration of the maintenance phase d. Adding calories back in at the needed pace a. A ddi ng i n i ni t i a l ca lo r ies When you cease trying to lose weight and switch into weight maintenance mode, calories will have to increase - for two reasons, initially, because of the direct Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 74 need for higher calories, and later, in multiple increases due to gradual metabolic increases. When you begin to add back calories initially, for most people, we recommend, starting with between 250 and 750 per day. For women over 200lbs, you’ll want to add closer to 750 calories per day and for women around 100lbs or less, you should start with adding around 250 calories per day. The more precise recommendation is this: let’s say you were losing at a rate of 1lb per week when you ended the diet. That means you were in a roughly 500 calorie daily deficit. In this case, you would need to eat roughly 500 additional calories per day to get to an isocaloric, maintenance level. This addition is made as soon as the fat loss diet is over. It seems like a lot of calories to throw in right away, but there is a very good reason for this; you want to move completely out of the hypocaloric state and into the isocaloric state. All of the benefits of the maintenance phase (which, remember, is crucial to allowing you to efficiently lose fat again later if need be) will not occur if you simply slow the rate of weight loss down; they only occur when you stop losing weight completely. The macronutrients to add in order to bring the diet back to an isocaloric state should be of the type you most recently subtracted to generate your deficit. For example, if you had to cut proteins (unlikely), add those in first until you’re at the recommended value for your LBM. If you cut carbs last, add those back in until you’re at recommended carb intakes for your LBM and activity levels. If you only cut fats during your diet, or have added less than the needed calories after bringing carbs back, then you’ll be adding fats back to make up that calorie deficit and turn the diet isocaloric. The prediction is that your weight will stabilize, but, for most people, that won’t happen right away. For about a week, your bodyweight has a good chance of going up 3-6lbs more than the weight at which you ended your fat loss diet just days before. Don’t freak out! This is completely predicted and explained in the next section. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 75 b. P re pa r i ng fo r a n in i t ia l blo a t reb o un d When you go back to eating any higher calorie or carb value than you are used to, additional water retention is a likely effect. Carbs, especially when you’re not used to eating them, can pull a considerable amount of water into your tissue. Combine that water with the water brought in by the high salt concentration of some of the “end of diet cheat meals” you’ll likely have, and voila! You’re 5 pounds heavier. The good news is that this weight will be off in a week or two at the most, so long as you’re actually eating an isocaloric diet. If you stop a diet and cheat like crazy, you’re likely to be very hypercaloric and just gain a bunch of actual tissue weight. As the water drops off but you keep cheating, the scale never drops and you’ll have actually gained the 5lbs or so. But so long as you stick to the plan and only elevate your average daily calories to maintenance, that 5lb bloat will drop off within a week or two, and you’ll be back to the your end-of-diet weight. Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 76 c. C ho o s i ng t he du ra t io n o f t h e m a in ten a n c e ph a se This phase should run anywhere from 1-3 months. The longer you’ve been dieting and the more you had to drop your calories from baseline (a big part of the equation), the longer your maintenance phase should be. So if the diet was a breeze and was only 2 months long, a one-month maintenance might be enough to get you ready to diet full steam again. For diets of 3 months in duration and/or those diets that truly drain you and push you to the limit with low food amount and high workloads, up to 3 months of maintenance dieting might be needed in order to re-establish normal psychology and physiology. By then, you’ll be ready for another bout of fat loss dieting, if needed or desired. d. A ddi ng c a l o r i e s b a ck in a t t h e n eed ed p a c e Let’s say you’ve added in the calories needed to erase the initial deficit, you’ve bloated up and then lost that bloat, and you’re on your way and planning on 7 more weeks of maintenance dieting. If you’re doing everything right, your weight should actually start falling within the second or third week. Why would it do that? Because your metabolism is speeding back up! The more speed your metabolism regains (it can take 2-3 months to fully ramp up), the more food you have to keep eating in order to keep weight the same and truly benefit from the re-setting effects of the maintenance phase. Every week that you register as underweight on average, add 250 calories to your daily intake from there on. These calories should fill in the rest of your deficit until needed values of protein (first), and carbs (second) are met. After that, add in healthy fats as much as needed to make sure you’re getting in enough calories to maintain your weight. The process of adding food to maintain may last between several weeks and 3 months, and is literally the symptom of your increasingly more rapid and “back to normal” metabolism. After the conclusion of the maintenance phase, you should Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 77 be eating a heck of a lot more calories per day than when you just finished the last diet, and at the same exact bodyweight. Now that your metabolism is back online and you have lots of additional calories to cut from your diet if you so choose, you’re ready to go back into another phase of hypocaloric fat loss dieting if you are not yet at your final goal weight. Continuing along with this loss/maintenance pattern is the most promising method of consistent and long term fat loss of which the authors are aware. That’s the nuts and bolts of dieting for fat loss. Next, dieting for muscle gain! References ENER GY BAL A N C E • What should I eat for weight loss? • Energy availability in athletes • Energy balance and body composition in sports and exercise • Sport Nutrition. An Introduction to Energy Production and Performance. 2nd ed. • Advanced Sports Nutrition • Diet, exercise or diet with exercise: comparing the effectiveness of treatment options for weight-loss and changes in fitness for adults (18-65 years old) who are overfat, or obese; systematic review and meta-analysis DIETIN G F O R W EIGH T LO S S • Evidence based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation • Adult weight loss diets: metabolic effects and outcomes Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 78 • Body composition changes after weight-loss interventions for overweight and obesity • Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standardprotein, low fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials • Effects if reducing total fat intake on body weight: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and cohort studies • The role of diet and exercise for the maintenance of fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate during weight loss • Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance • Effects of energy-restricted high protein, low fat compared with standard protein, low fat diets: a meta analysis • Role of protein and amino acids in promoting lean mass accretion with resistance exercise and attenuating lean mass loss during energy deficit in humans • Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise • Lean body mass-body fat interrelationships in humans SET P O IN T T H EO RY • Body weight set-points: determination and adjustment • Factors influencing body weight regulation • Do adaptive changes in the metabolic rate favor weight regain in weightreduced individuals? An examination of the set-point theory • The defense of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss • Is your brain to blame for weight regain? Chapter Two F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 79 P. 8 0 03 Dieting Procedures for Muscle Gain When setting up a strategy for muscle gain, similar to that for fat loss, there are steps to adhere to in the diet design process. We will walk through the steps of constructing an effective muscle gain diet based on the principles we learned in Chapter 1. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 80 Chapter Three In many (but not all) ways, muscle gain diet design is a mirror-image of fat loss dieting. Let’s look at the basic steps in designing a muscle gain strategy. Many will be quite familiar from the fat loss phase: 1. Establish a base intake for your stable bodyweight 2. Generate a caloric surplus to gain weight at the right pace 3. Calculate the amounts of proteins, carbs, and fats to take in to meet those calories, and follow the rules of timing, food composition, and supplements 4. Track bodyweight to make sure progress is on the right track 5. Adjust calorie and macro intake to keep bodyweight gain on track 6. Plan your diet duration for best results 7. Take time to re-establish your new set point and re-sensitize to hypertrophic (muscle building) processes before embarking on the next phase of dieting to gain muscle 8. If you want to keep gaining muscle, proceed into a fat loss phase after the maintenance phase and before the next muscle gain phase. Let’s take a close look at each of those steps, along with the corresponding recommendations in terms of executing them in the best way possible. There will be many commonalities with the fat loss structure, but important differences as well that we’ll make sure to note. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 81 1) E s t a b l i sh a b a s e i n t a ke fo r you r s t a ble b od y we i g ht In Chapters 1 and 2, we learned that the most important factor in fat loss dieting is the creation of a caloric deficit, at least in part by the reduction of calories being taken in per day. In much the same way, the most important factor for muscle gain is the presence of a caloric surplus - eating more calories than you burn. Before we can determine how much food to add to our diet in order to successfully gain muscle, however, we should look back and review the calories needed for maintenance: Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 82 TRAINING VOUME BODY WEIGHT LIGHT/OFF MODERATE HARD 100lbs 1500 1935 2400 125lbs 1650 2185 2650 150lbs 1850 2435 2900 175lbs 2050 2785 3200 200lbs 2300 3135 3500 225lbs 2550 3585 3950 250lbs 2850 4035 4400 275lbs 3150 4585 4950 300lbs 3550 5135 5500 Figure 4. (repeated): Estimated Average Caloric Requirements for Maintenance As previously mentioned in Chapter 2, this table is merely a rough beginning guide and tracking bodyweight to adjust calories to fit maintenance for every individual is needed. If your adjustments (using rises and drops of fat intake that amount to 250-500 calories at a time) lead to a stable weight within several weeks, you’re ready to begin altering the diet to increase muscle size! 2) G e n era t e a ca l o r i c s ur p l u s t o ga i n weight a t th e r i g ht p a ce. Since the most important factor in a muscle gain directed diet is the act of eating more than you burn, creating a caloric surplus is the most critical step of the process. Just as with a fat loss diet, however, there is an ideal surplus to aim for: • If the surplus is too small, we end up spending more time than needed to achieve our desired gains. Why gain 2lbs of muscle in 12 weeks if you could have done it in 8? Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 83 • Too small of a surplus, and we also run into a serious measurement problem. If you aim for a ¼ pound of weight gain per week, that’s 1lb a month. There is no scale you can buy at your local department store than can reliably detect such small changes week to week. Add body water fluctuations to that and you end up with the very possible scenario that you spend a whole month on a “gain” plan but due to scale error and water weight variability, you fail to detect that you’ve actually lost tissue and gained no muscle. Anything slower than ½ pound per week is not within normal instrument or bodyweight variability to detect. This means that females weighing close to 100lbs will need to gain weight at a rate closer to the 0.7% body weight per week pace to stay ahead of this 1/2lb figure. • Too large of a surplus, and we end up risking great fat gains. Fat will be gained at ANY rate of weight gain, but anything over 0.7% per week will just add to fat gains without increasing muscle gains. For a quick example, if two women weighing 150lbs train the same and eat well, but one gains 16lbs of tissue in 8 weeks and the other gains on 8lbs of tissue in 8 weeks, what will the likely change in muscle and fat be? What’s been found in research and coaching practice so far is quite jolting; both will (under great circumstances) gain roughly 4lbs of muscle. That’s right, gaining much faster than 0.7% of bodyweight per week leads to almost exclusively extra fat and essentially little or no extra muscle gain. So gaining too fast will just lead to your having to burn off twice the fat later! Based on the constraints above, it seems that the best range for a caloric surplus lies somewhere between 0.3% and 0.7% of bodyweight per week. This means that for a woman that weighs 150lbs, a very good start for a weekly weight gain goal is somewhere between 0.5lbs and 1.0bs. You’ll notice that this rate is lower than the fat loss rate, and that is indeed true. Especially for females, muscle seems harder (and slower) to gain than fat is to lose. Hold on a second…. do we have to gain weight in order to gain muscle? No, but the rates of muscle gain with no weight gain are abysmally slow in most people. The only lucky ones who can sometimes attain these elusive “lean gains” are people brand new to lifting or scientific dieting. If you are unwilling to gain weight under any circumstances, even temporarily, you will be reducing your Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 84 ability to gain muscle by roughly half. We will discuss the lean gains myth more in the “myths and fads” chapter at the end of the book. If you’re serious about muscle gain, you have to gain the weight. In order to generate our desired levels of weight gain, we’ll again use the estimation that a pound of tissue is 3500 calories. For fat, this is roughly accurate. For muscle, this turns out to be accurate because while muscle itself does not contain as many calories per pound of tissue as does fat, it’s much harder to build. In any case, we only have to be in the ball park with this initial estimate because later we’ll learn how to make much more precise adjustments to individual circumstances and physiologies. If a pound of tissue is gained with 3500 calories in surplus, we can assume that around 500 calories above base daily caloric intake is going to lead to roughly 1lb of weight gain per week in most situations. Thus, for our 150lb example woman, a 500 calorie surplus is going to generate the 1lb per week weight, 0.7% body weight per week gain we’re targeting. If you’d like to calculate your own projected surplus to start a muscle gain diet, just use the following steps: a. Choose your percent weight gain. Example: 0.5% per week. b. M ultiply your weight gain percentage by your current bodyweight to estimate weekly weight gain needs. Example: 100lbs x 0.005 = 0.5lbs per week. c. Multiply your weekly weight gain in pounds from b above by 3500 calories to get the calorie surplus number per week. Example: 0.5lb x 3500 = 1750 calories per week. d. Divide the weekly calorie surplus by 7 to get the average daily surplus: Example: 1750/7 = 250 calorie surplus per day. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 85 There it is, your daily surplus is calculated. Now that you’re on track to gain weight at the right pace by adding calories, we’ve gotta make sure those calories are coming from the right macros. 3) Ca l cu l a t e t h e a mount s o f p ro t e i n s , car bs , a n d fa t s t o t a ke i n t o me e t t h o s e ca l or ies , and foll ow t he r u l es o f t i mi n g , fo o d co mp osi tion, and s u p p l e me n t s . Once we have our maintenance intake of proteins, carbs and fats, where do we add the calories? Well, here is some information to make that decision straightforward: • Eating more protein than needed (above what is required for maintenance) does NOT have any special effect on muscle growth beyond what any extra calories will. • Eating more carbs is ok, but doesn’t improve performance or body composition any more than the extra calories would. Eating tons of carbs may also reduce insulin sensitivity by a small margin, making muscle gain harder than it should be. • Eating extra fats is cheap, easy, and tasty (adding fats to most anything makes it taste better, as evidenced by American Southern food or French cuisine). In the case of monounsaturated fats, fat surplus is also the healthiest and best option for body composition. So we will carry over macros and protein amounts from our maintenance plan and our primary source of calorie increases during most of the muscle gain phase will be via the addition of healthy fats. When beginning our calorie surplus, we now know what macros to start with. Let’s use our lovely 150lb woman example at 20% body fat who wants to gain at a 1lb per week pace (~0.7% body weight per week), and let’s again use her “moderate” training day as an example. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 86 Base Calories: 2435 Base Protein: 120g (1g of protein multiplied by 120lbs as her LBM) Base Carbs: 180g (1.5g of carbs multiplied by 120lbs as her LBM) Base Fats:137g (2435 total calories minus 1200 calories from protein and carbs, divided by 9 calories per gram of fats) We know that she needs to increase her calories by about 500 per day if she wants to gain a pound of tissue a week, so our new base calories are 2965. And because we’re going to add all of those in the form of fat, we’re going to leave our protein and carbs the same at first: Starting Mass Calories: 2965 Starting Mass Protein: 120g Starting Mass Carbs: 180g Starting Mass Fats:190g (2965 total calories minus 1200 calories from protein and carbs, divided by 9 calories per gram of fats) Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 87 Is there a problem in the math somewhere?! 190 grams of fat per day?!?! Nope, that’s totally fine. There is a lot of very tasty food that can be eaten to get in that much fat. And for most women in most circumstances, more carbs can be eaten too if the fats get to be a bit much. But hey, if you’re complaining about the high fats… do a fat loss phase to remind yourself of how awesome they are! The human body can absorb almost any quantity of nutrients thrown at it, so don’t worry too much about “having to eat too much fat.” If you’re more comfortable eating higher levels of protein or carbs to make up the calories, that’s totally fine for most healthy women, although in most cases fats will simply be the easiest way to take in a surplus. (That whole having 9 calories per gram thing comes in handy here – smaller masses of fat have more calories than other macronutrients and so they tend to be easier to eat when you are having trouble getting all the extra calories down). APP LY IN G T H E L AST T HR E E P R I NC I P LE S F R O M C HA P TE R 1 When programming your muscle gain diet, sensible timing is still important. Make sure you eat at least every 5 hours and make sure you have a post (or even intra/post) workout shake with weight training. Eat most of your carbs around training and keep the heavier fat meals farther away from weight training. Have a relatively even amount of protein in each meal. Spreading out your calories can make them a lot easier to take in. Intermittent fasting sounds great until you have 3000 calories and only 4 hours in which to eat them. While you’re slowly, but surely adding in all of these fats, don’t forget to keep in mind the food composition rules from the 4th principle of scientific dieting. Stick to mainly whole foods, including lean animal proteins, whole grains, fruits, veggies and healthy monounsaturated fats. At night, have your casein or milkprotein to keep amino acids levels in your blood high while you sleep. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 88 Cheat meals are just fine to get your calories up. Easing in to several gigantic cheat meals per week is a fine strategy for most people, though most of your surplus should come from planned high-nutrient-dense foods. Keep your supplement intake consistent and intelligent. Creatine is also a fine supplement to try when massing, but remember that you will gain some water weight during the first week of creatine supplementation, so keep this in mind when tracking your weight and don’t be fooled into thinking you are gaining additional tissue. 4) Tra ck you r b o dywe i g h t t o ma ke s u re progress is on t he r i g ht t rack. So our example woman increased her calories by 500 per day with the intention of gaining about a pound of tissue per week. How much muscle will she gain per week if she’s gaining a pound of weight? That’s a complicated question, but not an unanswerable one. Muscle-to-fat gain ratios depend on numerous factors, the most impactful of which are: • Training “age” (beginners gain more muscle and less fat) • Dieting “age” (those new to proper dieting will gain more muscle and less fat) • Genetics (various mechanisms allow some to gain lots of muscle while others gain more fat) • Training volume (the more you train up to the point of maximal recoverable volume, the more muscle and less fat you’ll gain) • Dietary precision (the better your diet is and the more consistent it is, the more muscle and less fat you’ll gain) • Body fat level (leaner people gain more muscle and less fat when they eat a hypercaloric diet – another good reason to cut after maintenance before a second gain cycle) Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 89 • The rate at which weight is gained (remember, at a rate of 0.7% or more bodyweight increase per week, much more fat is gained and much less muscle gained) • The single-stretch duration of a muscle gain phase (the longer a gain phase stretches, especially after 2-3 months of continuous weight gain, the higher the percentage fat gain and lower the percentage muscle gain) • Supplement use (those amazing before and after photos of physique women on Instagram where they seem to gain almost pure muscle on a gaining phase sometimes involve the use of anabolic steroids and other powerful supplements with other side effects that need to be carefully considered, especially for women) Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 90 If all of the above factors are perfectly aligned in your favor, you can gain muscle so fast that you’ll lose fat at the same time in order to feed the muscle growth! It must be mentioned and emphasized that this situation is incredibly RARE. IN most cases, there is a certain amount of muscle and fat gained at the same time. For the average athlete or fitness enthusiast, a ratio of 1/3 muscle to 2/3 fat is possible if the dieting and training process is done right. For individuals that have been training and dieting consistently for longer than 5 years and have gained plenty of muscle, 1/4,1/6 or even 1/8 muscle to fat ratios are not uncommon. One of the most important implications of these trends is that a fat loss phase will eventually have to be done after every muscle gain phase in order to maintain a given body fat percentage and not just get increasingly fatter with each muscle gain phase. Also, this fat loss phase will optimize subsequent muscle gain phases as mentioned. We’ll look into this implication much deeper towards the end of this chapter. Another important implication is that because muscle and fat are gained at the same time, we have to figure out a way to track how much muscle gain we’re actually experiencing so that we can adjust the diet if needed. The very first part of the answer is to track bodyweight. Because weight gain is so important to muscle gain, the only insurance we have that muscle gain is at least fairly well on track is weight gain. As per the guidelines for measurement on a fat loss phase, bodyweight should be taken 2-3 times per week and tracked so that expected rates (1lb per week, for example) are occurring. Secondly, since we don’t generally have the imaging technology readily available to check weekly to see if muscle is being gained, our additional measurement will be of strength endurance. Strength endurance is the measurement of how much weight you can lift (any lift… squat, bench, deadlift, rows, etc…) for reps of 8-12. This single measure correlates the best to muscle gains. Thus if you’re training normally and your 10RM squat and bench are moving up as you gain weight, Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 91 plenty of that weight is likely muscle. The more the lifts go up, the better, and the higher percentage of your total lifts go up, the better. For example, if only your bench went up but everything else is about the same, you may or may not be gaining adequate amounts of muscle. But if all of your lifts except your deadlift have steadily improved, you’re almost certainly on the right track. If you’re not gaining much strength endurance as a muscle gain phase progresses, you’ll need to reassess to make sure you’re doing everything right, just the same way you’d reassess if bodyweight wasn’t also climbing. Increase your calories by strategically adding in healthy fats, weigh yourself 2-3 times per week, and you’re well on your way. Usually this will result in a couple of weeks of well-paced weight gain. OK, so what is the procedure for getting weight back on track if weight gains slow after several weeks? Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 92 5) Ad j u s t ca l o r i e a n d ma cro i nt a ke t o keep b od y we i g ht gai n o n t ra ck. As you’re gaining weight, similar to losing weight, there are three possible scenarios: a. You are gaining weight at approximately the rate you want b. You are gaining weight too quickly c.You are either gaining weight too slowly for your planned rate of gain, not gaining any weight, or even losing weight Let’s take a look at each of these scenarios and talk about how to adjust when needed: A. O N - T RAC K W EIGH T GA I N Obviously this is a great place to be and requires no adjustment. However, there are associated pitfalls just as there were when weight loss was on track in our fat loss phase: • The temptation to try to gain faster. Because you should already be on track to make good progress, this move can cause two problems. The first would be that you burn out on eating excessively, thus the rest of your diet becomes less effective as you become more and more uncomfortable taking in the additional food. The second and perhaps more detrimental effect is that you end up increasing fat gain without any additional muscle gain. This just gives you more work later during the fat cutting phase. If its not broken, don’t fix it, as they say. If you’re gaining at the right pace, stay calm and enjoy your food and your strength gains! Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 93 B. RA P ID W EIGH T GA I N Body composition will be negatively impacted if weight gain proceeds much faster than 0.7% per week, so we’ll want to have strategies to deal with this possibility. If you gain faster than this, you’re just going to be adding that much more fat and in most cases no more muscle. That’s just fat you’ll have to get rid of later, which is bad for health, appearance (depending on your personal values, of course) and muscle retention when you have to diet hard to get rid of it. That being said, some leaner women might want the extra fat, and even benefit from it health-wise. If this is the case for you, then gaining a bit above the 0.7% per week might be a fine option. If you’ve only added fats, and not additional proteins and carbs, subtracting fats from the diet until weight gain returns to an acceptable pace is best. If you have added extra carbs in addition to adding fats, then subtracting some carbs from your intake is the first step in getting back to a good pace of gain. Again, the question arises: how many calories are we talking about changing? That can depend on the rate of weight gain, but generally, subtracting around 250 calories per day from the diet will be a good start. You can raise the subtracted calories to 500 if you continue to gain excessively after a week of taking away 250 per day. C. SLOW O R N O W EIG HT GA I N Though it is a problem to have slow weight gain, no weight gain, or even weight loss, the solution is fun – more food. In this situation, you want to follow the opposite advice of situation b and increase calories once a week by 250 per day in order to get weight to move up at the right pace. Even with the best designed diet, weight gain will begin to slow eventually for the following reasons: Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 94 • The longer you stay in a hyercaloric diet, the more your metabolism will ramp up. As it ramps up, you will need to eat more to keep your weight gain pace on track. • As your metabolism elevates, you’ll unconsciously move and fidget more throughout the day, causing an increase in total calories burned. • The more weight you gain, the more tissue you have that is metabolically active and burning calories. This is in addition to the ramping up of your metabolism via hypercaloric eating. To keep your caloric surplus you can reduce activity or add food. Physical activity is almost always healthy and generally leads to better body composition, so you probably don’t want to reduce this too much. Food on the other hand is awesome (ask someone on a hypocaloric diet, they will tell you in detail HOW awesome), so you’ll almost always generate a surplus by adding in food rather than reducing activity or training. So add your 250 calories per day in fats to get weight moving up, weigh in 2-3 times a week and continue to increase as needed. If you cannot stomach any more fats, start filling in the extra calories with carbs. By following this procedure, you’ll be insured of continual weight gain for the duration of the diet. Speaking of duration, just how long, exactly, should a diet be? 6 ) P L AN YO UR D IET D U R ATI O N F O R B E S T R E S U LTS Similar to the rules for diet duration when losing weight, gaining weight requires adherence to 3 basic rules: a. Create a weight gain goal b. Limit to a maximum pace of 0.7% weight gain per week c. Diet for no longer than 12 weeks at a time Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 95 Le t’s exa mi ne 2 exa m ple sc en a r io s: Woman X wants to gain 5lbs by her next Powerlifting competition. The competition is two months away. She weighs 160lbs. She’s got 8 weeks and 5lbs to gain, which gives her a desired weight gain of 0.625lbs per week. Her maximum allowable pace is 1.07lbs per week, so her goal is completely realistic and attainable within the 2 months she has allotted. Woman Y wants to gain 20lbs and she doesn’t quite care when, she just wants to be stronger and have a bigger booty ASAP! She currently weighs 110lbs. If she diets for the maximum duration of 12 weeks, she’s limited to gaining around 0.73lbs per week at a max pace. This means that 12 weeks of diet at the fastest pace will yield her just under 9lbs of weight gain. Woman Y must take a diet break and come back and gain the remaining 11lbs in another stretch of hypercaloric dieting. Why the need to pause the diet and come back later? Let’s take a look in the next section. 7) R e - E s t a b l i shi ng P s ych o l o g i ca l a nd Phy siologica l S ta t e s After a single stretch of gaining, its best to take time to maintain the new weight and then cut the excess fat gained during the hypercaloric phase before trying to gain more muscle. Why the need for this approach? Prolonged (12 or more weeks) hypercaloric dieting has the following effects on physiology and psychology: a. Increase of general fatigue via high workloads used to build muscle b. Decreased muscle gain rate due to higher body fat levels Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 96 c. Retention of set point at historically low body weight values d. Decreased hunger and desire to keep gaining e. Decreased motivation via change in appearance Let’s take a look at each one of these effects and explore what sorts of constraints they place on the duration of a diet. a. Inc re a s e o f ge ne ra l fa t ig ue via h ig h wo r k lo a d s used to bu i l d mu s cl e As the relentless damage of high training volumes continues to accumulate, fatigue will eventually rise to unsustainable levels that increase the likelihood of poor technique, poor performance, likelihood of injury and lower rates or a cessation of muscle gain. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 97 Temporary fatigue can be managed and tolerated, but at some point it must be reduced - and that means training volume has to be brought down. Low training volumes don’t support muscle growth (though they do help to maintain existing muscle) so switching to lower training as we switch to an isocaloric diet for maintenance work double time for an effective maintenance phase. Each reduce fatigue and lower training volumes has the added benefit of helping us keep the muscle we earned. Once we have trained with low volumes for some time, our fatigue has dropped and our growth machinery is back to full function, we can once again train hard and begin to lose the fat we’ve gained over the course of massing. But why can’t we just keep gaining instead? Exactly the topic of the next point. b. D e c re a s e d mu s cl e g a in ra te d ue to h ig h er b o d y fa t l evel s For reasons probably closely related to insulin sensitivity, leaner individuals gain a higher percentage of muscle when they train hard and eat a hypercaloric diet than do less lean individuals. That is, all else being equal, a leaner person can gain maybe 1/2 lbs of muscle per week where the same individual, if 10% higher in body fat, might only be able to put on 1/3lbs of muscle per week. While the exact mechanism of this effect is as yet unclear, the implications are very clear. If you try to gain mass for too long (over 12 weeks or so in most cases of appropriate gain rates), the fraction of the mass gained that is muscle starts to dip quite low, and the fraction of mass that is fat starts to rise. If this were not the case, you could be absolutely jacked by next year by gaining tons of weight and then trimming the fat off in a series of cutting phases. Alas, in real life, most of the gains in muscle would be at the very early stages of that mega-bulk, and most of the latter stages would be spent gaining fat with little or no muscle gain at all. Thus, once a gaining phase reaches the point of very low muscle growth per pound of tissue gained, the gaining phase is best stopped, with cutting phase done later to reduce the individual’s body fat levels. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 98 c. Re te nt i o n o f s e t p o in t a t h isto r ic a lly low b o d y wei ght va l u es As mentioned in chapter 2, the body has a way of getting used to a certain weight after a few months of being at that weight. It will generally try desperate to keep you at this set point, unless you carefully change that set point by cutting or massing and then carefully maintaining for a few months afterwards. The effect of this for fat loss is very straightforward; the more weight you gain, the more the body pulls you back down to your old weight. In the case of massing, if you’ve gone from 150lbs to 160lbs in 12 weeks, your body will try to pull your weight back down to your set point of 150lbs via various factors including metabolic increases and hunger level decreases. As with maintenance following a cut phase, you will have to carefully watch your weight upon completion of a mass cycle in order to maintain. After several months of maintenance at your new weight, your body will have a new set point at your new weight and will help you stabilize there instead of dragging you back down. In the figure below, the dieter starts out at 170lbs at month 0, and begins dieting around month 1 (point A). While her bodyweight (the thick blue arrows) falls at a predicted and linear pace down to her short term goal of 155lbs by month 3, her set point weight (dashed blue line) has not yet caught up and is still close to the initial 170 value. If she kept dieting, at this point (point A) it would be harder and harder to get lower. This is because her set point is still so high above her new body weight. By running a weight maintenance phase until point B, she allows time for her set point to get down and match her new weight of 155lbs. At that point (point B), her metabolism is ready for another round of hypocaloric dieting to get down to her goal weight of 140 without her body continuing to fight to get back to the 170ish set point. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 99 d. D e c re a s e d hu nge r a n d d esire to keep g a in in g One of your body’s most effective strategies, in its attempt to keep you at your set point weight, is the reduction of hunger levels as weight gain proceeds. The more weight you gain in one continuous streak, the less hungry you will feel. Interestingly, in contrast to a cutting diet, you will probably find yourself put off by the thought of high calorie foods like pizza and cupcakes while massing. People actually tend to find themselves craving diet foods like chicken and veggies! Your body is set on losing and getting back to its usual weight, so it is signaling you to consume lower calorie foods as a means to this end. At some point, eating turns into such a chore that motivation to continue can measurably suffer. Motivation can also suffer for other more conscious reasons as described next: e . D e c re a s e d mot i va t io n via ch a n g e in a p p ea ra n c e Let’s be honest. Even if we are dieting solely for performance gain and nothing to do with appearance, very few of us love getting fatter. During a muscle gain phase, the majority of actual weight gained even in optimal conditions is fat. This will inevitably start to change our appearance. We don’t want to make any value judgements in this book about how much body fat is preferable or not, solely for the sake of appearance, so we’ll let each reader decide for themselves. However, it’s simply a statement of statistical fact that most women (and men, while where at it) prefer to be leaner for the sake of appearance. Watching abs and muscle definition fade while pants get tighter can be mentally difficult to deal with leading to less enthusiasm to eat the extra calories to keep the gains coming. Luckily, mass phase is temporary and you have already learned how to take that fat back off at a later cut phase. So, take heed in the strength gains, ice cream treats and the comforting fact that you have acquired the knowledge to achieve leanness again later. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 100 Taking some time to eat at maintenance (neither gaining nor losing weight) reverses many of these compensatory effects. Taking the time to run a fat loss diet after the maintenance phase reverses the rest of them and allows the dieter to come back later and continue to gain more weight if desired or needed. After 3 months of gaining, you’ll start your maintenance phase. The purpose of this phase is to re-set every single one of the problems encountered in the discussion above (aside from those requiring actual fat loss). SOME GUIDELINES FOR DESIGNING A MAINTENANCE PHASE a. Subtracting initial calories b. Choosing the duration of the maintenance phase c. Subtracting calories at the needed pace a. Su bt ra c t i ng i ni t i a l c a lo r ies When you cease trying to gain weight and switch into weight maintenance mode, calories will have to drop for two reasons. Initially because of the direct need for lower calories, and in multiple later steps, due to metabolic decreases. The same rules used for initiating maintenance after a cut are instituted after a mass, but obviously in the opposite direction. You will need to reduce calories after the mass phase is complete in order to enter into an isocaloric diet. Start by subtracting between 250 and 750 calories per day for women weighing 100-200 lbs. To be more precise, you can subtract the same number of calories that your weight gain suggests you are in excess. So if you were gaining 1lb per week, you will need to remove approximately 3500 calories per week, or 500 calories per day. The macronutrients to reduce in order to bring the diet back to isocaloric should be the opposite of the ones you most recently added in order to generate a surplus. Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 101 You will likely initially lose 3-6 lbs in the first week or so, but this is not actual tissue loss; it’s just the bloat of the high calories and carbs coming off. Your weight will stabilize after a week or so. b. C ho o s i ng t he du ra t io n o f t h e m a in ten a n c e ph a se This phase should always run anywhere from 1-3 months, depending on how long and how aggressive your mass was. Smaller gains over shorter periods will require less maintenance time. c. Su bt ra c t i ng c a l o r ies a t t h e n eed ed p a c e Following a mass, decreasing calories to maintain an isocaloric state will require updating, just as it did following a cut. Only this time, you will progressively decrease caloric intake in order to stay in the isocaloric zone as your metabolism slows back down from its ramped up mass cycle state. Every week that you register as overweight, subtract 250 calories from your daily intake, starting with any extra carbs you added, then moving to fat reductions after that. The process of calorie subtraction may last between several weeks and 3 months and is the symptom of your slowing “back to normal” metabolism. Now that your set point is re-established to prevent needless muscle loss on a fat loss diet, you’re ready to go back into another phase of hypocaloric fat loss dieting if you so choose. Continuing along with this gain-maintenance-loss pattern is the most promising method of consistent and long term fat loss of which the authors are aware. To recap, you gain the muscle you want and gain some fat as well, re-normalize your metabolism and psychology with a maintenance phase, and then lose the fat gained during your muscle gain phase. Once you’re at a lower body fat level again, you can either head into another muscle gain phase, or begin a Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 102 maintenance phase if you just want to either stay at that bodyweight or prepare for yet another fat loss phase. References DIETIN G F O R W EIGH T GA I N • Nutritional interventions to augment resistance training induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy • Gaining weight: the scientific basis of increasing skeletal muscle mass • A brief review of Critical Processes in Exercise Induced Muscular Hypertrophy • Physiologic and molecular bases of muscle hypertrophy and atrophy: impact of resistance exercise on human skeletal muscle (protein and exercise dose effects) • Nutritional Strategies to promote post exercise recovery • Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise • Lean body mass-body fat interrelationships in humans Chapter Three F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 103 P. 1 0 4 04 Performance Dieting Strategies Most of this Chapter focuses on the nutritional challenges and demands of twice daily training. We will go over strategies to maximize both training performance during such days and the resulting adaptations. The second section of this chapter will describe the right way to cut water for a competition weigh-in and offer some day of competition eating guidelines. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 104 Chapter Four This chapter was designed for those of us who compete in sport or are looking to do so in the future. Competitive athletes train and eat to get the edge, which can mean many things including twice daily training, cutting water weight for weight class sports and eating in special ways on the day of competition itself. For those of us crazy enough to train twice a day, we’ve set aside an entire section of this chapter. For most of this chapter, we’ll focus on the nutritional challenges and demands of twice daily training and we’ll come up with strategies to maximize both training performance during such days and the adaptations to that performance. The second section of this chapter will describe the right way to cut water for a competition weigh-in and the last section will give some brief guidelines on eating on the day of a competition. Because women today are involved in so many types of sports, we can’t do justice to the discussion of specifics for any particular sport, at the expense of leaving out others. However, the basic guidelines we’ll lay out will set you on the path toward a sound foundation of twice a day training, water weight cutting, and competition day eating strategies for just about any sport. Twice Daily Training: Nutritional Strategies While most of us are content just training hard once per day (and then possibly doing some light cardio at another time of the day, which isn’t impactful enough to change nutritional needs), some of us are after the kind of body composition Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 105 and performance results that demand more frequent training. For those that regularly train hard twice per day, some unique nutritional challenges arise. The two primary challenges are those of recovering from and adapting to training. When you train just once a day and after you’ve eaten a couple of meals, you have plenty of energy with which to train hard and elicit adaptations. If you have already trained earlier on a given day, however, you might face an uphill battle in producing the needed intensity and volume of work in the second session to stimulate the needed adaptations that make that session a productive one. There’s no point in training twice a day if you’re just going to be wrecked from your first session and zombie your way through the second. If you cannot work hard during the second session, it will contribute almost nothing to your improvement. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 106 On the other end of adaptation, we know that once you train, certain adaptive processes begin to accelerate in your muscle, nerve, and other body cells. These are the processes that actually cause the beneficial changes from training, but they don’t start right away. Many of them take minutes, hours and sometimes days to get started and produce the changes you are looking for. Where the complication comes in is that with any hard training during this time of “adaptive initiation” the adaptive magnitude from the first session tends to reduce. That is, training hard after you’ve trained hard earlier that day can somewhat limit the positive effects the first session has on your physique and performance. Thus, our problem is twofold; we need to make sure we recover the most that we can after our first session so that our second can be productive, and we need to make sure that our second session minimally interferes with the adaptive momentum of the first session. Luckily, the way in which we eat and drink after the first session and before the second can have a meaningful effect on the net result of both sessions. Let’s take a look at some particular recommendations, but keep in mind that all of the same principles from earlier chapters (in which we assumed 1x per day training) still apply, even if they are not explicitly mentioned here. S prea d i n g t he S e s s i o ns A p a r t When we train, we want to both stimulate the physiology with an overloading workout (be it overloaded in weight, sets, reps, time, distance, speed, or whatever) and make sure that that overload is put to good use in stimulating adaptations. If we’re really going to be on our A-game and fully capable of the tough workouts that make us better, we had better be well rested. Thus, just from this insight alone, we’re going to recommend doing the second workout as far after the first as realistically possible. The longer we rest after the first workout, the more fatigue from the first workout will dissipate, the more we can eat and drink to refuel, and the better that second workout will be. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 107 In addition to giving us plenty of time to rest for the second workout, this big gap will allow many of the adaptive processes set in motion by the first workout to run their course, which ensures that the more of the benefits of the first workout will be realized. So, do we do our first workout at 5am and our last workout at 10pm? Not exactly. In a smaller but still meaningful sense, we have to consider the energy we have to do our first workout and the adaptive gains initiated by our second workout. If we don’t have any time in the morning to eat a meal or two (or to even wake up fully), we could be limiting how productive that first workout is. Secondly, we could be limiting the recovery and adaptation realized after the second workout if we just get home right after it ends and fall asleep face down with our workout clothes still on. In addition to being a poor choice for personal hygiene, just going to sleep after a second workout without eating can cut off the most opportune time for recovery nutrition and may have a small effect in limiting the adaptive magnitude stimulated by that session. From those constraints, we arrive at a likely recommendation. If you’re training twice in the same day and have large scheduling freedom, it’s probably best to do your first workout after a meal or two in the morning, and then your second workout in the early evening, with one or two meals or so to spare for after the second workout. This means that in an ideal setting, 6 to 8 hours will separate your first and second workouts. Of course we don’t live in a perfect world and we can’t get our schedules to accommodate such patterns all the time. But we can try to do our very best. How do we do our best in the real world? Just follow these three simple tips when scheduling your twice daily sessions: a. Give as much time as you can between AM and PM workouts. b. Give at least one meal in the AM before your first workout. c. Give at least one meal in the PM after your second workout, but two meals is even better. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 108 These recommendations are numbered by how important they are, so if you can do any one of them, do the first recommendation. If you can do any two, do the first two, and if you can do all three, great! Just remember to keep it simple and stress free. Just doing your best is your only goal. O rga n i z i n g S e s s i o n Di ffi cu l t y In most training program designs, you’re not going to have workout sessions of the EXACT same difficulty on the same day. Usually one of the sessions will be tougher than the other, though both may be quite taxing. If you have the freedom to do so, we recommend the following choice of session difficulty: Above all else, intensity should come before volume. If you have to hit heavy doubles in the clean and snatch at one workout and do high rep squats, pullups, and handstand walks in another workout the same day, it’s almost always best to do the intense (heavy and low rep) workout first and save the volume workout (lots of sets, reps, or distance) for the second workout. If you’re tired, you may experience technique breakdown and sheer lack of energy to hit the heavy high intensity work, but you can usually still crank out high reps, sets, and distances. And luckily, volume tends to fatigue much more than intensity, so you’ll barely feel those heavy cleans on your run, but you would feel every step of that run on your cleans. a. If you have the choice, make the first session the hardest one of the day. You’re rested after a full night of sleep and your last workout was yesterday. When that session really fatigues you, it’s ok because your next one will be the easier of the two. b. T he second best option if you can’t help it is to have the harder session later. Yeah, you won’t be fully rested for it, but at least the session preceding it in the day was an easier one, so you won’t be super beat up going into the second. c. T he worst option is to have a day with two equally difficult sessions (as far as volume is concerned, especially). If you have to hit a certain number of tough sessions in a week so that you can progress, it’s not a very good idea to put two of the hardest ones on the same day. This will limit both the energy you can put into the second one and the benefit Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 109 you get from the first. When designing a training plan, placing easier sessions with harder sessions should be the goal if 2x per day training is needed. If you can’t accommodate that and must train super hard twice on the same day, the world won’t end, it just isn’t the most optimal option. Just like with session timing above, the options for session difficulty are rankordered. You should always strive to make the top recommendations happen and use the bottom ones if your schedule simply doesn’t accommodate anything better. Th e Imp o r t a n c e o f I n t ra / Po s t Wo r kou t Sha kes If you’re training twice a day, the first session is likely going to utilize quite a bit of glycogen. Glycogen is the form of glucose stored in the muscles (and the liver to a much smaller extent) and provides you with the lion’s share of your workout energy. If effective workouts are the goal, maximum glycogen availability in the muscles is a big factor. If you consume a shake containing simple and high glycemic carbohydrates during and after training in the first session, you’ll not only spare some glycogen (especially that stored in the liver), but you’ll have the glucose in your blood to immediately begin repleting glycogen that was used up during that first workout. In the first-to-second workout interval, glycogen repletion is both very important and very time-constrained. We need to do our best to replete glycogen as fast as we can and as much as we can, since it’s likely to be a limiting factor if we don’t. Intra and immediately post-workout carbs for the first workout are a great start to this process. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 110 Hig h Ca r b In t a ke s B e t we e n S e s s i o ns Not only do we need to take in carbs during and right after we train in the first session, we need to make sure that those carbs are as high on the glycemic index as possible. High GI carbs digest quickly and appear quickly in the blood, raising insulin levels rapidly and leading to faster glycogen loading into the muscles and liver than lower GI carbs. In the research literature, high GI carbs have shown a more complete repletion of glycogen between repeat training sessions than low GI carbs, even when matched for carb amount. We need to replete glycogen as fast as we can and as much as we can, since it’s likely to be a limiting factor if we don’t. Thus, especially in the meal right after training, higher GI carbs are a very good idea to make sure glycogen repletion is occurring at the fastest pace. In addition, we know that fat, fiber, and very high levels of protein intake with carbs lower the glycemic index of those carbs and make their deposit into glycogen slower. We also know that moderate amounts of protein likely speed up glycogen repletion. So our best advice, especially in that first meal post first workout, is to consume moderate to high GI carbs (like low fat baked goods or sugary kids cereals) with minimal levels of fat and fiber, and some protein (just your usual amount of protein for one meal – in other words protein grams total needed for the day divided my meal number). Not only are our carbs going to be glycemic, but they’re also going to be eaten in large quantities. No matter how high the GI of a carb is, you’re going to need a lot of it to replenish first session glycogen loss. If you’ve got around 6 hours Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 111 between workouts, 1.5g of carbs for every pound of your lean body mass is a very good place to start, and much less is not recommended. That means a woman with 130lbs of LBM will be consuming around 195g of carbs in 6 hours, with most of that consumed by 2 hours before the second workout. During this inter-workout repletion period, re-establishing good hydration is also important. It’s even more important considering that each gram of stored glycogen requires around 3g of water to enter the muscle or liver cell with it. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 112 If you just drink your normal amounts of water and eat such high carb amounts, you’ll be lucky to not get dehydrated. Make sure you drink frequently and consider adding electrolytes to your water so that you’re peeing a lot and peeing clear within an hour of your second workout. Tot a l Ca r b In t a ke s Outside of the inter-workout period that occurs between the first and second sessions of the day, you’re still going to want to take in the carbs needed to give you energy for the first workout and begin your recovery from the second. Taking those needs into consideration, two hard workouts (as rated on the activity scale in earlier chapters) will require 2.5g of carbs per pound LBM per day, if not more in some cases. We recommend starting with 2.5g per pound of LBM and going from there. What does a day of eating for twice daily hard training look like? Here’s one example: Meal 1 7am: Egg whites, 2 pieces of fruit, 2 tablespoons nut butter Meal 2 10am: Lean turkey, brown rice, broccoli, 1 tbsp olive oil Meal 3 12pm: (intra/post workout shake): 25g whey protein, 75g Gatorade Meal 4 2pm: (right after first workout): whey protein, skim milk, two bowls of lucky charms cereal Meal 5 4pm: Lean turkey, brown rice, broccoli, 1 tbsp olive oil Meal 6 7pm: (post workout shake after workout 2): 25g whey protein, 50g Gatorade Meal 7 8pm: Grilled salmon, whole grain pasta, two tablespoons of nut butter Meal 8 Bedtime: One scoop casein protein, two tablespoons of nut butter blended to make pudding. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 113 Water cutting for various events When sports have weight classes, it often pays to weigh in at the top of the class. In other words, if you have to compete against women that weigh somewhere between 148 and 132lbs, it usually pays to carry as much muscle as possible and thus weigh as close to 148 as possible when fairly lean. If you want to compete at your best, have the most muscle and weigh in at the top of your class. The complexities emerge when the timing of weigh-ins becomes a factor. For various federations in various sports, the actual weigh-in time isn’t always right at the time of the event. In fact, sports can weigh their athletes for competition in 3 distinct temporal classes: • “Matside” weigh-ins, when the athlete is weighed in right before competition begins • 2 hour weigh-ins, when the athlete is weighed in two hours before competition begins • 12 hour weigh-ins, occurring 12 hours before the start of the competition (quite rare and usually the night before) • 24 hour weigh-ins, which are very common, especially in powerlifting and strongwoman As the weigh-in times are distanced further and further away from the competition time, an opportunity becomes incrementally more open; the ability to cut water weight and put it back on in time to by hydrated for competition. This ability makes sense because of one fundamental reality: the amount of body water (total water making up and being stored in the human body at one time) it takes to facilitate peak athletic performances is significantly higher than the amount of total body water it takes to keep you alive and well. If an athlete is euhydrated (optimally hydrated for peak athletic performance), they can typically lose up to 5% of their bodyweight in water (by urinating, sweating, and Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 114 breathing) and still be at minimal or no risk of any serious health effects. While anything over 5% is a gamble and anything over 7% is downright dangerous, most athletes can handle a 5% loss from euhydration and still be ok, so long as they don’t stay that dehydrated for longer than needed. If you can drop 5% of your water and still be ok, an interesting implication emerges. An athlete who is normally too heavy to compete in the 132-148 weight class, and weighs as much as 155lbs can drop around 7lbs of water and weigh in at 148, giving them an improved muscle per pound of body weight benefit. That’s a huge advantage, but ONLY if the water weight is regained before competition begins so that optimal athletic performance can be exhibited. This regain of water weight is critical, and leads us into our discussion of the complexities of cutting water for competition, because other than the total amount cut, it’s going to be our limiting step in how much weight we can successfully cut and still perform our best. The biggest limiting factors with weight cutting are the total weight cut (a maximum of 5% of the athlete’s bodyweight) and the amount of time they have to put that water weight back on in order to ensure best performances. With some of the best strategies for rehydration, returning to normal body water takes the following times, depending on the initial degree of dehydration: • 24 hours: 5% rehydration possible • 12 hours: 3% rehydration possible • 2 hours: 2% rehydration possible • Matside: no rehydration possible As you can see, the degree of rehydration possible depends highly on the available time to rehydrate. Additionally, the total amount of dietary and water intake manipulation that’s required to achieve a certain level of dehydration properly also varies based on the total dehydration amount: Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 115 • Dropping 5% body water requires around 1 week of setup • Dropping 3% body water requires around 4 days of setup • Dropping 2% body water requires around 1 day of setup The following table allows us to visualize these parameters more easily: WEIGH-IN TIME % BODYWEIGHT DROP SETUP TIME REQUIRED 24 hour 5% Approx. 1 Week 12 hour 3% Approx. 3-4 days 2 hour 2% Approx. one day MATSIDE BLOAT PREVENTION Night before/day- of Figure 6. Setup time required for various water cut strategies Now that we have our goals and constraints in place, let’s take a deeper look at the actual strategies involved in dropping water weight and then re-gaining it to successfully bring as much muscle per bodyweight to the competitive arena as possible. ***We first want to stress that cutting water weight can be dangerous if done incorrectly, or when there are pre-existing conditions involved. Please consult your physician before attempting any of the below dehydration techniques. Once you have your Dr.’s approval, follow the directions carefully and proceed with caution. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 116 24 Hour Weigh-In The 24 hour weigh-in involves, by far, the most intricate and detailed manipulations of food, water and body temperature. These manipulations are performed so as to successfully lose the most water possible, in the safest manner possible, and with the least fatigue incurred to the athlete so that they can successfully peak for performance shortly thereafter. Let’s begin at the beginning of the week and go step-by-step to see what changes we need to make. After the weigh-in, we’ll take a look at rehydration strategies, and then move on to the specifics of a 12-hour weigh-in. De p l e t i o n a. C a r bohydra te re d uc t io n One of the biggest reserves of body water lies bound up with the storage of glycogen. Glycogen, which is the complex carb stored in muscle and liver, is only constructed with the help of integrated water molecules. In fact, glycogen can store up to 3g of water for every gram of actual carbohydrate, and because females around 150lbs can store up to 500g of glycogen, they are essentially carrying another 1.5kg of water. If 75% of that glycogen-water total is dropped (500g glycogen plus 1.5kg water = 2kg total), that’s 1.5kg already, or 3.3lbs. With a 3.3lb drop at 150lbs, that’s already over 2% bodyweight right there! Glycogen reserves are burned off during both exercise and general daily tasks, so it will take around 5 days or so of special eating to drop glycogen to its lowest levels and thus lose body water. What kind of special eating? Well, a diet almost completely devoid (or as close as possible) of carbohydrates. The same calories as usual, but with close to no carbs means that more fats will have to be consumed. This low-carb diet starts a week out from the weigh-in and lasts all the way up to the time you step on the scale. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 117 b. Wa te r l o a di ng In order to set up for easy water loss later in the week, we have to make sure the hormonal axes that control water retention in the body are tilted towards diuresis (water expulsion). If they are tilted towards antidiuresis (water retention), water loss will be much more difficult, more extreme strategies will be required to drop it and these strategies cause much more fatigue. The most straightforward way to allow for diuresis to occur is to consume lots of fluids. Since none of the fluids can contain carbs, water and diet drinks are the best choice here. How much water? 1 gallon of water for 100lbs of body weight per day. Thus, a 130lb woman would consume 1.3 gallons of water each day, spread over the day in even amounts. This should be a good starting point for water intake during water loading, but the best indication of sufficient hyper-hydration is the frequent urination of clear urine. Remember that foods and even coffee also contain water, so you might not need to chug a full gallon of water daily to water load sufficiently – that is just a suggested starting point per 100 lbs. Hyponatremia (over-hydration) is extremely dangerous. To be safe, drink enough extra water so that you are urinating frequently (every few hours) and your urine is clear, but do not aggressively drink much more than a gallon per 100lbs. Watch for symptoms like nausea, headache, confusion, and muscle spasms or just in general, if you feel weird, consult your doctor and stop chugging. Getting to a state of hyponatremia is unlikely from drinking the recommended water amounts across a day for water loading, but it is important to be aware. It is also important to spread your water drinking out Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 118 across the day. Don’t blast through the gallon in one sitting. This will decrease absorption and can be dangerous. The water loading process begins at the start of the week and will continue through the fifth day. Thus if your weigh-in is on Friday morning, you’ll start loading water on the previous Friday and continue to drink the same ample amount until Wednesday night. c. S a l t re s t r i c t i o n Salt attracts more water into your cells than even glycogen. Thus, restricting salt intake is eventually going to be a strategy for eliminating body water. However, the hormonal regulators of salt concentration in the human body are incredibly sensitive, and will create an antidiuretic effect within hours of salt restriction. Thus, we’re going to wait until 2 days out from our weigh-in to cut salt. If the weigh-in is on Friday morning, this means that we’ll reduce our foods to as low-salt as we can on Wednesday morning but no sooner. Reducing salt intake any sooner will lead to an overcompensation by the rapid hormonal antidiuretic pathways and will make the last bit of water drop more difficult than it needs to be, thus requiring you to be dehydrated for longer. A big implication of this late cut of salt is that you must continue to eat normal amounts of salt all week beforehand. When you’re drinking all of that water until the last day of the water load, you need to be consuming your normal amount of salt if you want to prevent antidiuretic processes from switching on too soon. An easy way to do this is to continue to salt foods normally and drink some Powerade Zero (or comparable flavored beverage containing electrolytes but no carbs) to make up some of the fluid intake requirements. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 119 THUS FAR, OUR PLAN CONSISTS OF THE FOLLOWING • Restrict carbohydrate intake as low as possible until weigh-ins have occurred • Drink approximately a gallon of water, per 100lbs of bodyweight, per day from 1 week out until one day in advance of the weigh-in • Take in normal levels of salt until 2 days before the weigh-in, then, reduce salt intake to that which is naturally available in low-salt foods and no higher During the water loading, your weight will actually rise for the first several days as you hyper-hydrate. As your water regulation pathways adjust to the higher water intakes and induce diuresis and as glycogen depletion from your low carb diet occurs, your weight will fall around 3% by the 24hour-out mark. Great! Almost all the way there. d. Wa te r re s t r i c t i o n At 24 hours before the weigh-ins (in simpler terms, the morning of the day before), we begin our water cut. The task is simple; we only consume enough water to be able to swallow our food and nothing more. Because of the built up diuretic drive of the last week or so of water loading and the release of water from glycogen stores and lowered salt intakes, the first half of the day will continue to be (as the whole week has been) punctuated by heavy urination of clear urine. Because you’re taking in almost no water to replace this lost urine, your weight will start to fall considerably, and you’ll likely lose another 1% or so during the first half of this day. That’s great, cause now we’re approaching 4% of our total body weight in water lost! e . Fo o d re s t r i c t i o n In the final day before the weigh-in, we want to make sure we’re as light as possible. This means we can even make sure to have very little food in our digestive tracts! Yes, poop does weigh a bit, and the less of it we can be “full of,” on the competition scale the next morning, the lighter we will be. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 120 Reducing GI tract material and fecal weight is accomplished by eating very low volume foods and those low in fiber, since fiber tends to attract water. The usual fare of chicken, olive oil and broccoli is replaced with eggs or protein powder. Our best in-house recommendation is casein pudding. Casein protein is perfect for preventing muscle loss during this time as it provides a steady stream of anticatabolic amino acids, as well as being very low in volume. Just two scoops of casein protein mixed with 2-4 oz of water provides a low-volume pudding that has 50g of high quality protein and not much else. f. H y pe r t he r mi a Our final piece of the puzzle is put in place in the last 12 hours or so before the weigh-in itself. We’ve dropped just about all the water we can without actually increasing sweat rates, so it’s time to turn up the heat. By increasing our body temperature, we can initiate sweating and drop a considerable amount of weight very quickly. The big negative is that hyperthermia (an elevated body temperature) is very fatiguing and not safe for long periods, so we must use 3 precautions here: • Already be very dehydrated from the previously mentioned means so as to limit the need for hyperthermia • Not overheat to an extreme (sauna, for example) for longer than 20 minutes at a time without cooling off • Be observant of our physical and mental state and back off and cool down if vision starts to blur, coordination reduces, or muscle weakness presents For that last 1% or so of bodyweight, hyperthermia can be used safely and effectively in two main ways: • Wearing warmer-than-needed clothes for the last 12 hours before a weigh-in. This will cause low-grade sweating at a safe body temperature for the whole 12 hours. If you’re ok sleeping and relaxing while a bit hot, this is a great choice. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 121 • Using a sauna or hot shower/tub within the last several hours (morning of weigh-in) This process needs to occur first thing the morning of the weigh-in, around 4 hours before the meet weigh-in starts. 20 minute bouts of intentional overheating can be broken up with 10 minute bouts of cooling back down to be both safe and effective. These bouts of overheating can be accomplished in a number of ways, all of which work comparably well: • Take a hot shower • Wear warm clothes into your bathroom, run the hot shower behind the curtain as you sit on the toilet with the lid closed and the door shut • Go to a formal sauna at a gym • Use a hot tub at a gym • Sit in your own bath tub with the hot water running. DO NOT DO THIS WITHOUT SUPERVISION (and in fact the whole process of hyperthermia would benefit greatly from supervision) • Have a friend drive you to the meet in their car (if it’s several hours away) and wear winter clothes while they wear summer clothes and blast the car’s heat into your direction Be very careful with hyperthermic methods and always make sure to stay safe. Sports are nothing to get into health trouble about. After you’ve cut your water and weighed in, you’re on target and ready to rehydrate and refill your glycogen and salt stores! Up next, the repletion section! (You are about to feel much better – the below strategy is incredibly effective but not a whole lot of fun, especially on the final hungry, thirsty, weak day of the weigh in). Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 122 To summarize, here is a timeline table of the ‘24 hour weigh in’ guidelines for dropping approximately 5% body weight: S T R AT E GY BEGINS END Car b Depletion 7 days ou t At weigh-in Wa ter Loading 7 days ou t 24 hour s ou t S a lt Depletion 48 hour s ou t At weigh-in Wa ter Depletion 24 hour s ou t At weigh-in Food Volume Reduction 24 hour s ou t At weigh-in Hyper ther mia 12-4 hour s ou t At weigh-in Figure 7. Twenty-four hour weigh in water cut timeline R e p l et i o n The replacement of the lost bodyweight after the weigh-in has occurred is as important as the weight cut itself, because only with full hydration can we expect our best performances. We know we’ve replaced adequately when our weight is at a stable weight equivalent to or even slightly above our starting weight a week earlier, before the water cut started. If morning weight on the day of the competition is still lower than usual, aggressive repletion methods need to continue until normal daily training weight is reached. Why are the repletion methods after a water cut termed “aggressive?” This is because, during a repletion, we’re fighting against the clock. Every hour takes us closer to the need to be fully repleted at competition, and every one of those hours must be spent on the serious business of re-establishing bodyweight. What are those aggressive repletion methods? Essentially, they are just the consumption of Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 123 the lost substances en masse; namely water, salt, and carbohydrates. In addition, we’ll be making sure that we do our best to reverse the fatigue accumulation of the water cut, and for that, we’ll need high calories as well. Let’s go through the list of substances which need repletion and discuss the specific recommendations of their intake after a 24hour-out weigh-in. a. Wa te r As almost all of the actual weight dropped during the cut is itself water, the most critical component of repleting after the cut is getting back a sufficient level of water. The minimum amount is around 1 gallon / 128 oz per 100lbs of bodyweight. Thus a 150lb woman needs to get in 1.5 gallons over the next 12 hours. Since this is a minimum amount, in reality more will often need to be taken in. We give you this value of 1 gallon per 100lbs to guide you to at least getting a good start on water repletion. You shouldn’t need much more than that, but the best indicator is urine color on the morning of your competition. Shoot for a gallon per 100lbs the day before you compete (first 12 hours of repletion), and then drink plenty of fluids overnight if you wake up for whatever reason. If, by the morning, your urine is very clear, you’re good to go and can resume normal hydration practices. If you’re still peeing yellow or darker, continue to consume more fluids than usual to bring yourself up to normal hydration by the start of the competition. A big help to the rehydration process is to remember that almost any fluids can count towards your intake goal. Gatorade, fruit juice, and most any other beverage work. If they have too much sugar, they will make you thirstier and you’ll drink more water just out of thirst. We recommend going about half plain water and half carb-heavy beverages to make sure you add a sufficient amount of fluids. The last tip on water intake is very similar to the process of water loading during Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 124 the cut; consistency and moderation are the key. If you chug a gallon of water right after you weigh in, most of that water will get peed out anyway, as it’s usually too much for your muscle and other cells to absorb. In addition, you’ll be risking hyponatremia. But if you have 32oz of water with every meal and you sip on sugary beverages and water in between meals and with snacks throughout the day, you’ll absorb and replete much more of that water, and be less uncomfortable doing so. b. C a r b ohydra te s Just as with water, carb repletion needs to be slow and steady, and most of it done within the first 12 hours of the repletion. In that timeframe, you need to consume around 5g of carbohydrate per pound of bodyweight. That’s right, which means women who weigh 150lbs will be eating 750g of carbs during the 12 hour period after the weigh-in! If that sounds like a lot, you’re right! The depleted physique will need all of that carbohydrate to replete glycogen stores completely to help you perform your absolute best on the next day. On the upside, it’s a rare instance where such massive carb intake is recommended, so enjoy! Just like with water, there is a limit to the absorption and glycogen assimilation rate of carbs. Eat any faster, and you’ll either get sick to your stomach or you’ll add more fat and less glycogen than you could have. In general, 1g per 2 hours per pound of bodyweight is a good working limit. Thus if you weigh 125lbs, you’ll want to limit your carb intake to around 125g every 2 hours. But that means after 4 hours you can consume 250g total, and after 8 hours you can be up to 500g total, and 10 hours after weigh-ins you can meet your minimum goal of 625g. In the case of carbs, the minimum and the usual are pretty close together, so there’s not much need to stuff far beyond that. However, getting any less carbs than 5g per pound bodyweight is not recommended. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 125 The carbs you get in should be tasty, relatively low in fiber (to enhance absorption and prevent feeling full too early in the day), moderate-to-high glycemic (to enhance absorptions speed, glycogen loading rate, and total amount loaded), and a combination of solid and liquid sources. Say goodbye to brown rice and fruits because the fun carbs have their day today, with the following sources recommended: • Low fat cookies, cakes, snack crackers • Kids cereal • Low fat “baked” potato chips • Skim chocolate or lowfat chocolate milk (lactose free for the intolerant) • White bread and white rice • Sub sandwiches, sushi and burritos • Non-caffeinated soda (to prevent diuresis) that is NOT DIET • Fruit juices of any kind • Frozen yogurt c. C a l o r i e s High calories must be consumed in at least the first 12 hours of repletion for two reasons. First, a hypercaloric diet is one of the best fatigue fighters, and the depletion process can have a noticeable effect on raising fatigue just when it needs to be as low as possible. High calories in the day before competition will ensure that everything has been done for minimal fatigue and thus maximal preparedness. Second, if recommended carb amounts are eaten with inadequate calories, much of the carb intake will go to fueling normal body activities and thus not get incorporated into glycogen reserves as needed. In this case, calories become our energy buffer so that as many consumed carbs as possible can be used to rebuild the glycogen we need them for. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 126 The rough recommendation for the first 12 hours after weigh-ins is around 30 calories per pound of bodyweight. This means that a 100lb woman will eat 3000 calories in that time period and a 180lb woman will eat 5400 calories. That’s a heck of a lot, but hey, someone’s gotta do it! Protein should be consumed at around 0.6g per pound of bodyweight in that 12 hours and not much more. Protein is highly filling, which will make the eating process harder than needed. In case you’re worried, 0.6g of protein in 12 hour is more than enough to stave off muscle catabolism. Fats should be consumed to round out the remaining calories, so a target of 0.85g per pound of bodyweight is a rough guide. Be careful not to overeat on the fats and keep fiber low as both of those nutrients will delay nutrient digestion and absorption, which will make getting in the much needed carbs harder than otherwise. You don’t have to stuff yourself far beyond these listed values for calories, carbs and fats, but getting in at least these values, especially for carbs, is going to be a very good start. d. S a l t You’ll need plenty of salt to help you reset sodium levels and retain water in order to rehydrate, but too much salt can leave you too bloated to eat the most you can, and can even make you sick. Don’t over-salt your foods, but make sure your repletion day diet contains salty items like low fat chips, burritos, sushi (with soy sauce) or sub sandwiches. If you feel like salting your food for taste, that’s great, but don’t just do it because you feel you have to. Most people will have no problem getting in enough salt with their normal repletion diet. To help you visualize a resulting structure to these recommendations, below is Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 127 a sample meal plan for the first 12 hours of repletion as well as the next morning (the morning of the competition): Right After Weigh-Ins: – 48oz water mixed with 90g of Gatorade powder and 20g of whey protein 30 Minutes Later: (Meal) –A Subway deli meat sandwich with a bag of Baked Lays potato chips and water 2 Hours Later (Meal): – A burrito with 2 glasses of regular Sprite In-between meal snack: – A Bag of low fat cookies with chocolate skim milk 3 Hours after last meal (Meal): – A Panera bread sandwich with a bag of low fat potato chips and water In-between meal snack: – ¼ of a light devil’s food cake with a glass of skim chocolate milk 3 Hours after last meal (Meal): – Sushi, and lots of it, with water In-between meal snack: – Round 2 of the Devil’s food cake and chocolate milk 3 Hours after last meal (Meal): – Chinese food until you’re too tired to eat to finish out the night If all goes well, you’ll wake up the next day feeling nice and full, you’ll be peeing clear, and you’ll be ready to perform. For breakfast that day, have a meal similar to one of your main meals the day before and be sure to hydrate plenty. Once you’re into the competition, eat as is outlined later in this chapter in the section about competition-day eating! Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 128 12 Hour Weigh-In The 12 hour depletion and repletion guide is very similar to the 24 hour guide, but with a couple of notable exceptions. Thus in this section (and the following ones on 2 hour and Matside weigh-ins) we’ll keep things simple and just focus on the important differences between these approaches and the 24 hour cut. The biggest difference in the depletion of the 12 hour cut is that without as much time to replete, our ambitions of water weight loss must be lowered from the 5% cut of the 24 hour weigh-in to a 3% cut. This presents us with a bit of good news regarding the difficulty of the cut. We can now entirely axe one of two processes; either the water loading at the front end or hyperthermia at the tail end. Whichever you decide you don’t want to do, just make sure to leave the other and its associated steps and do it well. If we really had to take a precise look at it, the hyperthermia is probably the best process to leave out, mostly because it’s significantly more stressful and thus fatiguing than the water load. But, the water loading is time consuming and annoying, so we leave the decision to you. Rest assured that from a performance standpoint, which one you choose is splitting hairs. After you remove either the hyperthermia or the water loading, just run the cut exactly like the 24 hour weigh-in depletion. Easy! Once you’ve weighed in, the biggest factor to consider for the repletion of the 12 hour condition is that only half the time as the 24 hour weigh-in is available for repleting lost water, salt, carbs, and calories/energy. But the good news is that this is balanced out by the more limited 3% weight loss. We’ll take the water, carbs, protein, fat, and calorie recommendations from the 24 hour weigh-in and multiply them by 3/5’s. That’s what we’ll be consuming Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 129 during our 12 hour repletion period. This means: • Water should be consumed at a minimum of 0.6 gallons / ~77oz per 100lbs bodyweight • Carbs should be consumed at 3g per pound bodyweight • Protein at 0.35g per pound body weight • Fats at 0.5g per pound • Calories at 20 per 100lbs Most of that should be consumed in the first 4-6 hours, as adequate sleep is required and 12 hour weigh-ins are usually done the night before a competition. A very good idea is to set aside a couple of snacks for when you wake to urinate at night. Some low-fat cookies and low-fat chocolate milk makes for a great midnight munch that will help you fill back out completely overnight (annoying to eat and probably r-brush teeth throughout the night, but if you are interested in being competitive, you are probably already used to doing uncomfortable things to prepare and get an edge). An extra glass of water to wash that concoction down might not hurt either. If you’re one of those people that simply doesn’t wake up at night to urinate even if your bladder is on the verge of exploding, an alarm for the middle of the night might be a good idea to remind you to consume your set-aside snack. 2 Hour Weigh-In The two hour weigh-in recommendations are radically different from the 24 and 12 hour weigh-ins. With such a short time to replete lost water and substrates, a much simpler and less aggressive depletion and repletion strategy must be used. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 130 The day before the weigh-in (as well as the morning-of, before the weigh-in has occurred) must be: • Low food volume • Trace carbs • Low/no salt • No water only in the last half of the day You can water load for a 2 hour weigh-in, but that’s usually not required. Just eat and drink normally until the day before, and then follow the guidelines above. The morning-of has the same guidelines, with no water (and minimal food of low volume) being consumed until the weigh-in has occurred. Once the weigh-in is over and 2 hours are left, the repletion guidelines are just as simple as the ones for the depletion: • Water should be consumed at a minimum of 0.25 gallons / 32 oz per 100lbs bodyweight, probably erring closer to 40oz • Carbs should be consumed at 1-1.4g per pound bodyweight • Protein at 0.2g per pound body weight • Fats at 0.25g per pound There is no calorie recommendations here, as 2 hours out it’s much more important to go by fullness and feel. A very important recommendation however is to consume all of these nutrients AS SOON AS POSSIBLE after the weigh-in. This gives the carbs and water time to find their proper storage areas and forms in the body. After an hour or so, you can begin sipping water, energy drinks, and/or sports drinks as-needed to get ready for the event. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 131 The kinds of meals that fit well in this scheme are typically subs, sandwiches, sushi, rice, pasta, or any other sources of carbs and lean protein paired with soft drinks, sports, drinks, and/or low fat chips. Matside Weigh-In Matside weigh-in strategies come with more restrictions than they do recommendations. Because you have to be hydrated right there and then, water dropping of almost any kind will tend to decrease potential performance. Almost of any kind. There are two loopholes we can potentially exploit. The first is that for strength/power sports (weightlifting, powerlifting, strongman), 1% dehydration is unlikely to negatively affect performance. Competitions with a higher endurance component do not hold the same benefit and thus full hydration is the only option for them. Second, while euhydration (full hydration that promotes best performance) is the best approach, hyperhydration (more body water than needed) is not usually helpful, and in sports in which your own bodyweight must be moved, even mild bloating can be a negative. Our Matside weigh-in recommendations and restrictions reflect these realities. For all Matside weighins in which making weight is a concern, overly salty foods should be avoided the day before and morning-of. That’s right, if you are competing with friends on the same weekend and you’re doing Matside while they are doing 24 or 12-hour weigh-ins, no Chinese food or sushi fun for you. For strength/power sports, athletes just 1% heavier than their target Matside weight can make sure to follow low food volumes on the day of the event, as well as drink the minimal amount of water during that whole pre-event morning that will keep them from being thirsty. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 132 Other than those simple tips, if it comes down to a Matside weigh in, using the earlier chapters of this book on slowly and steadily losing fat is the best way to make sure you’re on weight and ready to perform. And as always, no matter the kind of depletion you do… be safe! Competition Day Eating Because there is such a wide range of sporting events that the modern fit woman enjoys, we’d have to dedicate an entirely new book to the many classes of sport and the many detailed kinds of eating for maximum competition day performance in those sports. So we can’t give much detailed advice here, but we can give you a short list of strategies to use no matter what sort of competition you engage in. Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 133 TIPS FOR COMPETITION-DAY EATING: 1) Make sure to eat plenty of carbs and calories in the days leading up to competition day Every sport requires fatigue to be minimized for top preparedness and nearly every sport benefits from maxed-out glycogen levels. Unless weight cutting modifies this process, your goal in the 3-4 days before competition should be to consume adequate calories to maintain your weight, and plenty of carbs, to the tune of 2.5g per pound of lean mass per day, in most cases. 2) Eat and drink regularly throughout the competition day During competition day, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by the competition itself, watching teammates or competitors, meeting new friends, or the emotions of excitement or nervousness. Do what it takes and eat regularly through the day to make sure you’re properly fueled, and drink water and electrolyte beverages to make sure you’re hydrated. 3) Eat foods you’re used to The last thing you want to have happen to you on competition day (short of injury) is an upset stomach. Not only can this adversely affect performance, but the reduced ability to consume or absorb nutrients further worsens the problem. By sticking to your usual foods, you reduce the risk of having an adverse reaction to a food you’ve never tried or haven’t eaten in a while. This is especially important advice during a competition day because your stomach is already likely to be sensitive from nerves alone. 4) Eat and drink as soon as one event is finished If you’re in a sport like powerlifting, strongwoman, or the many other sports that have multiple events throughout the day, spread by hours of intervals, you’re in luck. This gives you the chance to replete lots of fluid, glycogen and calories between events so that you can do your very best in each one. Make sure you capitalize on this type of timing. Because food takes time to digest and fluid takes time to hydrate, eating and drinking as soon as your event is over is Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 134 critical. The last thing you want to do is to eat too late and risk being sluggish, getting sick or puking during the next event, or worse, missing the meal entirely and zombie-walking your way through that next event. 5) Avoid super high protein, fat, or fiber foods When you’re performing multiple events per day and taxing your body to its limits, the resources (mostly in the form of blood supply) it will make available to aid in digestion and absorption are already scant. Your blood is busy feeding your muscles and won’t be directed to your stomach and digestive system as much as usual. Couple this with the ‘fight or flight’ state in which you’ll likely be spending most of the day, and digestion and absorption are even more limited. Add on top of this the demand of having to exert yourself every 1 to 3 hours and there’s even less time to digest or absorb anything. Foods high in protein, fat and fiber require more energy and take longer to digest than foods higher in carbs and lower in fiber. Stick to white breads, smaller portions of lean meats, less fatty condiments and plenty of liquid foods in order to ensure your chances of success. Yeah, it’s a weird way to eat, but hey, you’ll be back to eating normally the night of the competition, after it’s all said and done. Well, maybe the next day, cause what’s a competition without a ridiculous meal of high carbs and calories afterwards?! Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 135 References T RA IN IN G & D IET IN G F O R P E R F O R M A NC E • Sport Nutrition. An Introduction to Energy Production and Performance. 2nd ed. • Periodization 5th Edition: Theory and Methodology of Training • Principles and Practice of Resistance Training • Glycemic Index in Sport Nutrition • Hydration and muscular performance: does fluid balance affect strength, power and high intensity endurance? • Development of hydration strategies to optimize performance for athletes in high intensity sports and in sports with repeated intense efforts • Nutritional Strategies to promote postexercise recovery • The use of carbohydrates during exercise as an ergogenic aid • Advanced Sports Nutrition • Practical Sports Nutrition Chapter Four F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 136 P. 1 3 7 05 The Psychology of Dieting Success at both dieting and sports performance is very dependent on a good mind set. Perspective and psychological habits can profoundly affect success in any endeavor.This chapter will outline the design of a successful diet from a psychological perspective, to help you increase your chances of getting the results you want from the diet you have designed using the earlier chapters. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 137 Chapter Five If dieting was all about the physiology of eating and training, we could stop this book right here. You could simply eat for your goals like a machine and fitness would be just around the corner. Fortunately or unfortunately, human beings are not robots. We are not only physiologically complex, but psychologically complex as well. Psychological differences between people, and even differences in mental state within the same person over different periods of time can have a great impact on their dieting success. While we’re busy learning about the physiological details of successful performance and fat loss dieting, we had better take a good look at the psychological side as well. Within this chapter, we will outline the design of a successful diet from a psychological perspective, to help you increase your chances of getting the results you want from the diet you have designed using the earlier chapters. The Psychologically-Informed Dieting Process There are 5 main organizing guidelines that are worth our special attention. There are other important guidelines to be sure, and this is not an inclusive list, but considering these 5 guidelines and following them is very likely to help with the process of successfully sticking to a dietary intervention. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 138 1) Cl e a r L ong Ter m Goals If you don’t know where you’re going on your next vacation, how do you know what to pack? How do you know what plane tickets and hotels to look at? How do you know what languages to brush up on? How do you know which of your friends to ask for recommendations? How do you know if you can afford the trip? How do you know if the trip is somewhere you want to go? How do you know if it’s even worth it to go? Everyone knows that the very first order of planning a trip, is deciding where to go! So if we’re all in agreement that a trip to nowhere is not a great idea, then we can acknowledge a very related concept; beginning a diet without a long term goal is similarly silly. It sounds obvious, but many clients come in for diet coaching with questionnaires listing goals as “gain muscle”, “lose weight”, “maximize strength”, “get lean” all listed as goals for a single 3 month diet. Perhaps this Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 139 is a side effect of not having read this book yet and not realizing that phases of muscle gain and fat loss happen independently. It can however also be evidence of a state of being unsure ‘where’ they want to go in their diet endeavor. A long term goal can mean many things, but to be sure “I have no idea” is not one of them. Long term goals can include: • What you want to perform like in 3 months • What PR’s you want to set in 6 months • What you’d like to look like within a year We could plan longer than a year at a time, but then we risk taking our “goal” and turning it into more of a “wish.” If we plan too far ahead, we’re left with “just train eat and keep getting better” as our plan, which isn’t really a plan at all and something we were going to do anyway. It’s our sincere advice to you to keep most of your goals within the one-year time horizon. And hey, if you achieve those goals, you can plan your next year accordingly. Not only should goals exist, they should also be clear. If you want to be better at bodybuilding, that’s just fine. If your crossfit performance is the big focus, great. If you wanna put pounds on your total within the next three months, cool. If you just want to see your abs and look like the athlete that you are, also great; we all love to look good. But make sure you understand that goals come with tradeoffs. “I just wanna get better” is NOT a goal. Do you mean leaner? Lighter? Stronger? More muscular? Better at the squat, bench, and deadlift? Even a combination of those goals is just fine, so long as you Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 140 understand that the combination is your goal and you’re willing to accept slower progress in all of those sub-goals if they cannot be worked toward simultaneously. What happens if you don’t have a clear goal? There are 4 negative possibilities that come to mind: a. L o s s o f mot i va t i o n When you have no goal and times get tough in the gym or on the diet, what do you tell yourself? Well, we’re not sure, which is one of the reasons we recommend having a goal! It’s tough to cheat on your diet with that piece of cheesecake if you’ve got a meet coming up for which you’re on track to make a weightclass. It’s unlikely that you’re going to stand in front of figure judges and know that you could have looked better had you not fallen off the wagon multiple times during the diet. There will be many times on a tough diet during which you will ask yourself “why am I even doing this?” Your long term goal is the answer to that question and has a very big effect on your motivation and consistency. If you have no answer to that question and your goal is “just trying to lean out a bit” (which is not remotely clear), having that extra piece of cake you know you shouldn’t doesn’t seem like such a big deal, so you wind up derailing any progress towards your vague goal. While many women find the process of fat and weight loss rewarding and motivating in and of itself, many of those same women struggle mightily with attempts at gaining muscle. The uptick of the scale, the increase in dress size and the disappearance of your favorite muscle definition can wreak havoc on motivation for muscle gain. When gaining weight, many females are fighting one or more of the following - their personal preferences for appearance, most of society’s norms (often reflected in the mildly rude comments from grandparents or Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 141 parents as to recent weight gain), a lifetime of cultural indoctrination, and, most powerful of them all, genetic programming designed to encourage them to be smaller, not bigger. Gaining muscle requires at least a temporary gain in weight, especially if you’re leaner to start with, so the motivation to do this must be the highest we can engineer so as to maximize the chances of successfully pulling off a mass gaining phase. If you have a clear goal of “I’m very focused on gaining muscle,” and not just “I want to look better,” you’ll be able to better resist the temptation to scrap your muscle gain phase halfway through and revert back to fat loss for no good reason. b. L o s i ng a s e ns e o f t im e -to -ta rg et If your long-term goal has been to lose 50lbs and you’re down 25, you’re halfway there! Yay! Blow up the balloons and invite the clowns; it’s you’re ‘halfway-there’ party! Comparatively, if your long-term goal barely exists, or is the ill-defined “I’d like to get leaner,” how do you even remotely know where you are in the process? If you don’t even know how long your journey will take, you might find yourself pretty disparaged and under-motivated. (Think back a situation like this in some cardio class you might have taken…..if you are told to do 25 sit ups, you have a definite end point and can probably blast through 25 - no problem. If, however, the instructor just yells “Do sit ups until I say stop!”, you might take a break after 15; you have no idea if the end is in sight or how much to conserve or exert energy in order to make it to the unknown end.) Knowing how far you’ve come and how much further you have to go can allow you to prepare for reality, expend your psychological energy wisely, and push hard when you know the goal is close (and save the hard pushes for later if the goal is still further away). Successful dieters don’t cheat a week out from their bikini show, and they don’t cut out all the fun foods on week 1 of 16 in their Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 142 show diet. But if you have no idea how long the road to “getting leaner” is, your strategy and motivation will suffer. c. P robl e ms de te r min in g rewa rd a n d c o m plet io n If you don’t know where you’re going, how do you know when you’ve arrived? Do Olympic sprinters continue to run past the finish line, Forrest-Gump-Style, around the track until officials restrain them? Of course not, because they know that celebration of their victory and planning for the next race begin right as soon as they cross that line. And in a big sense, your long term goal is that finish line. If we don’t diet to enjoy at least the results, then why the hell do we diet at all? If you don’t have a long term goal, when is your party? Never? When you finally give up and break down? What kind of party is that? And if you don’t have a goal to finish, when are you supposed to choose a new goal and make further strides? Having a clear long term goal, along with progressive mini goals that support it, will go a long way towards motivating you to succeed. This strategy will allow you to reward yourself for your accomplishments, hopefully to enjoy them fully, and to intelligently plan your next goal, even if that next goal is “establish a healthy and balanced eating pattern at this bodyweight, forever.” d. P robl e ms wi t h c o n sisten t p ro g ra m m in g Internet diet and training authority Martin Berkhan once coined a less than-PC, but phenomenal and hilarious term; “Fuckarounditis.” Martin defined this state of affairs based on fickleness often seen in lifter/dieters. When someone changes their focus of training once a week, changes their diet goals once every two to three weeks, and starts using new exercises they saw someone else recommending on Facebook the very same day they saw them, that person can be diagnosed with Fuckarounditis. The problem with this state of affairs is that when you give your Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 143 body too much variation in stimulus, it tends not to adapt to any of those stimuli very well, so the net results tend not to be anything that could be described as successful. If you have no clear long-term goals for your dieting process, you might end up switching directions so often that you go nowhere. One week you’re cutting, and the next week you’re cheating a bit too much and oh well, you might as well add some muscle by massing. In two weeks, you’re feeling a bit bloated from the massing so you start cutting again. 4 days into that, your CrossFit competition comes up, which means you carb load the night before and party the night of, so there goes your cutting phase. At the end of that month or so, where are you in terms of progress? Probably where you started or close to it. But if you began a well programmed fat loss phase at the start of that same month instead and stuck to it from the get-go, you could have been down 5-7 pounds already and seeing visible changes in your appearance along with improvements in your performance. We don’t recommend having long term goals just because it sounds nice or because everyone else says so. We recommend them because they work. They work to make dieting easier, simpler, more straightforward, more effective, and more rewarding. If you start dieting for either fat loss or muscle gain and you don’t know why or where you’re headed, or when you need to get there, consider stopping and thinking it through before you proceed. Ten minutes of planning can save you months of time and effort. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 144 2) S p eci fi c S ho r t Te r m G o a l s While long term goals anchor the outline of our motivation and direction, short term goals allow us to steer the ship and keep it pointed in the right direction. Short term goals can be between a month and a week in length, and allow us to make the adjustments we need to keep on track. For example, imagine that your goal was to lose 15lbs in 3 months (long term). How would you go about making sure you were on track? If you want to be maximally effective, you cut up the 15lbs into weekly chunks. 15 divided by 12 is 1.25, which is the average amount of weight you’re going to have to lose per week if you want to reach your longer-term goal of 15lbs in 3 months. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 145 Now you don’t just have a hazy goal off in the horizon somewhere, you have a map with which to plan out your every step. If your initial diet keeps you losing at about 1.25lbs per week, you don’t change a thing and just coast along! If your initial diet is too slow and you only lose .5lbs per week, you need to cut calories, increase expenditure, or maybe even do both so that you can meet your short term goals weekly. If your diet is too aggressive and you lose 2lbs per week at the start, you can eat more food to slow the process down and prevent muscle loss. Of course, in order to have the kind of short term weight goals that help you tremendously with staying on track and achieving your long term goals, you need to use your mortal enemy… THE SCALE. If scientists tried to design a machine that makes women question their very self-esteem and value, they’d have to work long and hard to better the common bathroom scale. To many women, the scale is a value-laden instrument designed to make them feel guilty about how skinny they could be and shame them for how skinny they’re not. It doesn’t have to be that way. Let’s step out of teenage insecurity and dependence on a number for our self-worth. You’re a goal-oriented mature adult on a mission. An adult who understands that athletes move, and this movement requires muscles. These athletes come in a wide variety of body sizes and shapes, but all have the similar goals of gaining muscle, losing fat, and improving performance to different extents. The scale comes to this arrangement only as a tool and nothing more. If you calmly and logically decided to drop from 155lbs to 140lbs over 3 months to improve your performance and appearance, the scale will help you tremendously with staying on track for those goals. If you weigh yourself with no goals or no healthy and stable lifestyle in mind, you won’t find any magic in the number of protons and neutrons that compose your body, which is fundamentally what the scale really measures. It tells you little to nothing about your goals, appearance, health, or performance. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 146 Short term goals, especially those of body weight change, are very helpful in keeping you sane and on track for accomplishing your goals. The next question is the effect of the speed of weight loss and gain on psychology. 3) Op t i ma l Bo dywe i g h t Ch a n ge Ra t e How fast or how slow dieters attempt to lose weight during their fat loss phases seems to impact not just physiology (how much fat they lose and the amount of muscle they spare), but psychology as well. It turns out that the recommended weight loss rate we discussed in Chapter 2 is also psychologically beneficial. SUP ER SLOW W EIGH T LO S S From a physiological perspective, there is not too much wrong with losing weight very slowly. If you’re able to keep very close track of your food intake and Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 147 your activity, it’s quite possible to detect and replicate a loss of around 0.25% of your body mass per week. For a 150lb woman, that translates to about 1.5lbs of tissue lost per month, which is very tough to detect, but perhaps not impossible. One thing we can say for sure about this fat loss rate is that it’s definitely safe for muscle retention. Speeds of loss that slow present only a tiny catabolic risk to muscle that’s easily overcome with proper diet and training. Simply speaking, risk of muscle loss is minimal. There is, however, a non-physiological problem with such a slow weight loss. It’s been shown in well-controlled studies that those dieters whom attempt needlessly slow weigh loss rates (under 0.5% per week and perhaps even as high as under 0.75% per week) experience greater dropout rates and weight re-gain after the conclusion of the diet. The top hypothesis is that super-slow weight loss rates are destructive to motivation. Seeing steady noticeable results is a very powerful motivator, and super slow diets just don’t deliver the goods in that regard. A very related approach to going super slow is the looser approach of “just eating healthy.” Eating healthy is fine, but there is no good reason to think that just healthy eating will result in noticeable and meaningful fat loss. You can eat just the same number of calories healthy or not, so if your goal is weight loss, you need a more precise plan. It seems from both the literature and our extensive work with clients through RP that most people do best with faster rates of weight loss, between 0.5% and 1% bodyweight per week. What about the alternative? How does super-fast weight loss affect psychology? SUP ER- FAST W EIGH T LO S S From a strictly physiological perspective, we can say that weight loss paces past 1% weight loss per week (especially 1.5% and above) are bad news. The caloric deficit is so great that fatigue skyrockets, training suffers, hunger and cravings become disproportionately intense, and muscle loss is likely. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 148 This hunger and performance loss ends up impacting the psychological side as well. How hard is it to stay motivated when you’re constantly exhausted, with all aspects of your athletic performance going downhill? How hard is it to stay motivated when you’re starving day and night and your mind is telling you to eat everything in sight? Super-fast loss rates look appealing because they can make even daunting weight loss goals seem less out of reach. Even the most willful of dieters however, can be worn down and overwhelmed with the monotonous brutality of an overly aggressive diet. This can result in cheating on the diet (with the equally brutal accompanying guilt), a change of diet goals during the middle of the process (tell yourself 155lbs is an ok place to stop the diet instead of the 150lbs you originally planned), or an even worse result -a complete cessation of the diet itself. Now, you’ve expended a ton of effort, reached no goal, and to top it all off, now likely have a super negative feeling about dieting. Between the extremely slow and the overly aggressive rate is our sort of golden band of weight loss pace. Weight loss rates between 0.5% and 1% of body mass per week seem to be not only comfortably within the physiological constraints, but psychologically sustainable as well. Are they sustainable indefinitely? Not a chance, which brings us to our next section. 4) Ma i n t e n a n ce P h a s e s So, we’ve got our optimal dieting pace and we’re good to go, now, let’s start dieting for a whole year and reach our goals! Wait, wait… we can remember that in earlier chapters there was mention of a limit to individual stretches of dieting, especially for fat loss. The limits already mentioned were physiological, but it turns out there are psychological ones as well. As mentioned earlier, diets exceeding much more than 3 months in duration tend to run into some physiological difficulties. After several months, high fatigue levels become unsustainable and training volume and intensity begin to Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 149 drop, muscle growth mechanisms give way to muscle-burning mechanisms, and rebound, muscle loss and injury become much more likely. In addition, the body moves further and further away from its set point. Metabolic rates fall, requiring even deeper cuts to calories in order to sustain progress. The brain responds to these trends mostly by raising hunger levels and by dropping unplanned activity levels. Diet for too long and you’re super hungry and super lazy, not nearly the kind of environment that sustains fat loss, but most certainly one that greatly promotes cheating on the diet or worse, ceasing it completely. After every 2-3 month period of dieting, a maintenance phase can allow the dieter to not only re-set physiological mechanisms, but psychological ones as well. 2-3 months of maintaining the achieved weight while eating more and more food to accommodate an increasingly re-accelerating metabolism can be a psychological godsend to promote recovery from the stresses of dieting and prime the dieter for another bout of fat loss. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 150 Because of the isocaloric environment of the maintenance phase, the intense hunger of the preceding fat loss phase is quickly relegated to minimal or entirely non-existent. As plentiful food is consumed, normal energy levels are returned and daily activities become much easier again. Training feels fresh and new and your body feels recovered and strong. After 2-3 months of maintenance eating, the hardships of dieting seem distant and the motivation to tackle them anew is back to normal. Now you’re ready, both physiologically and psychologically, for a new round of fat loss dieting. So do we just diet infinitely with maintenance phases? When do we get to live life? What about balance? 5) T he R i g ht Ti m e fo r B a l a nce If you’re always dieting or re-establishing your physiology and psychology for another round of dieting, when is the time for balance? Isn’t there room for eating the foods you love AND getting the body and performance you want? There is, but the process is sequential rather than concomitant. FIRST you get the body you want, and THEN you enjoy the foods you love. To be clearer, there is quite a bit of enjoyment of the foods you love during each maintenance phase. We can’t just diet with no end, so periodic maintenance phases are a temporary return to balance, both physiological and psychological. Do we need maintenance phases for balance? Can’t we just diet with balance built in? By definition, no. The very act of creating a hypocaloric environment is what leads to weight and fat loss, and it is by definition throwing the body and mind out of balance. You must eat less than you burn, which is the opposite of balance. In fact, the more efforts you make to “live a normal life” (by eating tasty foods high in calories), the slower your weight loss is – you need the temporary imbalance to facilitate the change. Thus, the more you try to mix balance and fat Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 151 loss, the worse the results for fat loss and the longer you have to diet and remain out of balance. The good news is, diets, as discussed extensively, are temporary. To achieve almost any goal, work is required and the work needed for fat loss is temporary imbalance. Taking all of these concepts together, the psychological dieting landscape seems to have 3 recommended states, with two of them being temporary and one of them being indefinite in length: Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 152 State 1: Dieting for Weight Change (temporary) State 2: Maintenance/Recovery Phase (temporary) State 3: Balance of Fun, Eating, and Training (indefinite) The first psychological state that seems best in the short term is that of focused, quick (but not too quick), and diligent dieting, whether for fat loss or muscle gain. This state is very effective for body composition changes, but not sustainable for periods longer than about 3 months at a time. In addition, diet phases shorter than about 1 month at a time tend not to accomplish very much body composition change, especially not when traded off against the restrictions typical of such a phase. Thus, for psychological and physiological purposes, we typically recommend diet phases to last between 1 and 3 months. The second possible state is the maintenance phase. When the focused diet state comes to its inevitable end, a maintenance phase must be initiated to recover the individual from the physiological and psychological disruptions of the diet state. Within 2-3 months (sometimes shorter or longer), the maintenance phase has returned the dieter back into dieting form, and at that point another focused diet can occur if needed. This initial phase following a weight change diet requires more attention to weight than subsequent periods of maintaining when your set point is established and you can relax a bit in terms of your eating precision. Once the dieter has achieved the body composition they find at least temporarily satisfying, they can enter into the third state; balance. The state of balance (otherwise known as a balanced lifestyle) is really just a maintenance phase that’s been indefinitely extended. In this state, the dieter continues to eat a fundamentally healthy and sport-oriented diet. The dieter continues to be active and train hard, but can also enjoy many of her favorite foods in satisfying amounts. By eating just a bit less “clean” and continuing to train hard, the dieter can rely on the body’s proclivity to remain in homeostasis, thus holding a stable Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 153 bodyweight for months and years on end. If the occasional extended holiday produces 5lbs of weight gain, a period of several weeks of lighter eating can and will return the body back into its normal weight range. The dieter can remain in this healthy and enriching state of balance for as long as she chooses, and this is where some big misconceptions about the relationship of dieting and balanced lifestyles lie… The key is choice, and the big question to the dieter is “what do you want to do?” Sit down, relax, and do an honest self- assessment. Think about how you’d like to look in an ideal world and think about how much you enjoy your balanced lifestyle of food, friends and fun. Remind yourself that if you are going to diet, you’ll be giving up a lot of that food and fun for a few months straight. If your balanced lifestyle is more important than an ideal body, stop self-criticizing IMMEDIATELY and ENJOY YOUR LIFE; you only have one, and spending it in a state of purgatory is just no way to live. If you calmly give it some thought and decide that changing your body is more important than being balanced for the next 3 months, it’s time to diet - and with no ‘if’s, ‘and’s or ‘but’s. Once you’re dieting, focus and be diligent, and do what it takes. Commit to those 3 months fully or don’t do it all. Halfhearted dieting does not achieve goals, AND has the added pain of making you feel guilty. It’s the worst of all scenarios; you are neither changing your appearance nor enjoying your life! Don’t do this to yourself. All or nothing is the way to go. Once you’re done with a bout of dieting, you really must enter the maintenance phase - none of this “I want to lose 5 more pounds while I’m in maintenance” crap… that’s not maintenance then, is it? When you’ve been in maintenance for 2-3 months and your metabolism and psychology have re-set, you’re ready to make your next decision. Don’t make any decisions on an empty stomach, Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 154 and don’t make any decisions on a post-diet metabolism and mindset; only decide your next move when you’re well into the maintenance phase and feel recovered. Take another look at your body and go through the same calculus again… what’s more important to you for the next several months: balance, or further enhancements? Remember that you can’t have both at the same time and that there is NO RIGHT ANSWER, only YOUR answer. Once again, whatever decision you make, dive in completely and don’t torture yourself with doubts. If you’re honest with yourself during this decision making process, you’re going to be both effective at dieting when you need to be, and happy and balanced when you choose, instead of trying to do it all at once or choosing a different option every other day. Make decisions and stick to them and you’ll not only be in great shape, but you’ll be happier too. What’s the point of a great body if you don’t ever enjoy living in it? Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 155 THE MAIN IDEAS OF DIETING AND BALANCED LIVING ARE AS FOLLOWS: a. Choose the phase you want to be in. The choice is really between dieting to change your bodyweight (up or down) or continuing to live in balance at your current weight. When in balance, it is highly recommended that you make plans for selfassessment no more often than once every 2 months, and preferably once every 3 months or longer. That way you don’t get into the habit of judging and evaluating your body all the time, and you can be much more objective when you do sit down to decide your next move. b. C hoose your phase based on two considerations; desire for appearance/ performance and desire for the benefits of a balanced lifestyle. For example, let’s say you want to be leaner for the start of the summer, and it’s currently March. Yu look at your calendar and find that you’ve got no wedding or special events for the next 2 months. You’ve kind of had your fill of going out to eat, and you’re super pumped to get to work and make some serious body changes. You know you’ll be missing out on some tasty foods and nights out for the next 2 months, but you’re totally ok with that because you have a super fun summer planned and want to look fantastic in your new bikini. This is a good example of when the choice to diet is the rational one. On the other hand, imagine that it’s mid-October. You’re pretty lean on account of your last diet, and your maintenance phase from that diet ends in a week. You could totally diet again, but you’re going to your significant other’s hometown for thanksgiving this year and his sister makes the best pumpkin pie you’ve ever had. You have a ton of holiday parties and you’ll even been cooking for a few of them. You’re already booked for an all-inclusive vacation in the Caribbean in early January. You’d like to do a regional CrossFit competition in May, but that leaves you with Feb-April to seriously diet. In this case it’s probably worth more to you to live a balanced lifestyle of hard training, healthy eating, and the occasional wild party and food coma through the holidays than it is to grind a fat loss diet through this time and alienate yourself from all the fun. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 156 c. M ake the choice as a commitment for the whole duration, which is specified in advance. This means that extenuating circumstances aside, when you start an 8-week diet, you do it 100% for all 8 weeks. If you have chosen to be in a state of balance, relax and don’t look in the mirror and judge yourself and consider every other day whether or not to start a cut, just enjoy and plan another evaluation session at 3 months. An evaluation session is when you calmly sit down (having arranged it months ahead of time, not in the heat of the moment after you felt fat at that wedding last weekend) and plan your next move. You carefully go through step b above and decide what you want to do for the next 2-3 months. Whatever it is that you decide, you will stick to it. d. You make a full psychological commitment to your chosen state. This recommendation is pretty obvious when it comes to fat loss and maintenance dieting, but the importance of this step may be less obvious when you’re considering a commitment to muscle gain dieting, and especially to a balanced lifestyle. FAT LO SS When you’re making a serious commitment to the fat loss diet state, you are clearly understanding that hunger is likely to pester you with cravings and that your energy might be low at times. These annoying symptoms are indicators that the diet is working! We have a motto at RP – assuming your weight loss is within the target pace – hunger is fat dying! Savor it. Only by cranking hard and being tough about hunger pangs and not-so-great workouts can you be consistent enough to see the diet work. If you choose to indulge in off-diet treats too often, you won’t see the results you want in fat loss, and losing the same amount of fat will take much longer than needed. You’ll finish the diet without meeting your goals, and what did you get out of it? You still suffered plenty, but you also didn’t quite meet your goals and Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 157 you topped it all off with a layer of added guilt. Not the best state of affairs… food doesn’t taste the same when it’s seasoned with your own guilt anyway. Save your cravings for the maintenance phase when you can enjoy the food guilt free. M A I NTE NAN CE By committing to the diet phase, you have by necessity committed to the maintenance phase. There is a big temptation on maintenance phases to do one of two things: eat everything in sight or continue dieting a little to lose more weight. The first will just erase all of your hard work and the second will mess up your mind and your body. Not only will you lose muscle, but you could risk developing an unhealthy relationship with food, which, as we’ll detail later, can take many months from which to recover. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 158 M US C L E GA IN The commitment of the muscle gain phase seems easy at first… any woman can eat a bunch more food and gain weight! Bring it on! Well, not always. One morning, you’ll wake up and see some temporary bulging, or find you cannot button your favorite pair of jeans without the dreaded muffin top effect. Your once-prized abs and shoulders are fading away and you feel like people don’t see you as a serious athlete because you don’t look shredded in your tank top anymore. Maybe your significant other made an innocent compliment about how s/he thinks your “new belly is cute”. It might be cute to some but you hate it… why not stop the diet right then and there and begin cutting again? Because then you will never gain the muscle you want. It’s imperative to understand that the muscle gain phase almost always comes with plenty of fat gain, but, and this is an important ‘but’, fat is super easy to diet off after the upcoming maintenance phase, revealing your new muscle and high performance. Focus on how strong you are getting and how much control you have over your weight, appearance and performance, thanks to your knowledge about dieting and your mental fortitude. Going through a muscle gain and maintenance phase is extremely healthy for women. Let’s pour our self-worth into what we can accomplish, rather than into how we (temporarily) look! (And then, subsequently also look awesome as well! Double win.) BAL A N C E This one is not always obvious but it’s very simple. You make a commitment to the balanced state because you’re not a teenager anymore. Commit to enjoying this phase and not self-judging. During this time, you can schedule your sit downs every three months and consider whether or not you want to change your body, but as long as you are in it, enjoy it and don’t stress about the next step. There will be enough stress when you take that step. You started your fitness journey to be happier, not more neurotic. The balance phase must have built-in Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 159 checkpoints for self-evaluation every 3 months or so because if you don’t restrict your self-judgment to a single time and place, it will pester you relentlessly and ruin a whole lot of fun. At the end of the day, your choice isn’t really between commitment to the phase or not. Your choice is about what kind of woman you want to be. You can be the kind of woman that always criticizes her own body and hates the way she looks, but doesn’t have the follow-through to commit to a diet and stick Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 160 to making the changes she wants to see. Or you can be the kind of woman that sticks to the plan, loses the fat or gains the muscle, and spends the rest of her time sampling delicious foods, drinking with friends, and living the life she wants in the body she built. The choice is yours. Psychological Resetting for the Diet Process Properly followed, the psychological approach to dieting described in the last section will yield great results both physically and emotionally. More often than not, you’ll feel calm, cool and collected, and even through the hardships you won’t be likely to lose touch with your deep motivation. Above is our ideal case, but let’s take a moment to talk about what to do if you have made some mistakes before reading this book or learning about proper dieting. If you’ve run a diet for far too long, too harshly, or in too rapid a succession with other diets, your motivation can go south. The result, in some relatively rare cases, can be a development of an unhealthy relationship with food. To be VERY clear, we are NOT talking about the development of formal eating disorders. Orthorexia and Binge Eating Disorder (or the lower probabilities of Anorexia and Bulimia) are very serious medical conditions and require the personal intervention of a psychologist or psychiatrist. If you have symptoms of such disorders and you’re concerned, schedule an appointment with a licensed therapist in your area as soon as you can. Not all eating problems are formal disorders, however, and most are milder and can be dealt with on your own with proper understanding. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 161 If you’ve been over-dieted, you may be noticing the following characteristics: • Dread of further dieting • Aversion to traditional diet foods like chicken and rice • Intense cravings for junk food that don’t go away much even when you indulge them • A growing hatred for the practice of counting, measuring, and restriction of food • Recurring fantasies of eating everything you want and never having to diet again • All of the above symptoms starting at the beginning of a new diet rather than at the end (a few of these feelings at the end of a diet can just be normal feelings that will resolve quickly during the maintenance phase) The last point is very important to consider before moving forward. All of the above symptoms are not entirely uncommon at the end of a grueling diet, especially if you’ve made big changes to your body or you’re down to an alltime low body fat. However, when they occur to a high extent in the middle or even the beginning of a diet, you might need to step back and deal with this issue before moving forward. Ideally, you just need a longer maintenance phase or even a maintenance phase (of roughly 3 months) followed by a balance phase of another 3 months. But since those phases still require at least the rough counting of macronutrients and/ or calories, even this kind of loose diet may be too much for some when they’ve really burnt out on dieting. In extreme cases, we encourage you to seek personal help via a professional therapist, in addition to resetting (described below), but sometimes the rest described below can be enough to get you back into a healthy state and ready to start manipulating your diet again. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 162 The 4-Step Reset The diet resetting process we describe here is based on a combination of psychology and nutrition science. It’s a 4-step process that can help many people progress from a total aversion to dieting back to a normal relationship with eating and goal-directed dieting. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 163 The big caveat is this: each phase, especially the earlier phases, can last months. Each journey is personal, but the maximum reasonable speed with which you can get through the whole process and still benefit is unlikely to be much less than 6 months. If you’re going to do this resetting, you’re going to have to take your time and do it right. If you’re truly fed up with dieting and on your last nerve with restricted eating, then getting back into a normal relationship with food can very much be worth between 6 months and a year of commitment. Looked at it from another perspective, half a year or a year of your life is pocket change compared to the decades that can be spent in needlessly miserable avoidance of the very tools with which you can craft the body and performance you want. As mentioned, because this is a long process and sometimes terrifying to those who have done a lot of dieting, the assistance of a therapist can be very valuable to help you through the process. Without further ado, here is a list of the resetting phases with a brief description of each one: PHASE 1: UNATTACHED EATING • Goal:Eating freely with zero concern over food choices whatsoever • Purpose: Easing the psychological burden of dieting and greatly reducing negative relationships/habits with food and eating • Typical Duration: 2-4 months • Completion: When you can honestly look forward to cleaning up your diet again Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 164 PHASE 2: NUTRITIOUS CHOICES • Goal: Eating with no calorie or nutrient requirements, but focusing a bit more on healthy food intake. Eating minimally processed foods that are high in protein, fiber, and vitamins and minerals • Purpose: To re-establish healthy habits without the pressures of counting and tracking • Typical Duration: 2-3 months • Completion: When you no longer have any fears or doubts about gently controlling your food intake PHA SE 3 : R O UGH MAC R O S • Goal: Eating nutritious foods and adding in the goal of getting rough (via eyeballing or handfuls) intakes of protein, veggies, and healthy carbs with each meal • Purpose: To get you back in the habit of eating well-rounded meals and some semblance of structure • Typical Duration: 1-3 months • Completion: When you are making sure to get the roughly correct amount of protein, veggies, and healthy carbs in each meal with no stress, out of sheer habit PHA SE 4 : C O UN T IN G A ND M E A S U R I NG • Goal: Beginning to count macronutrient amounts either daily or in each meal • Purpose: Getting used to the idea and process of counting your intake, WITHOUT yet having a goal number to hit • Typical Duration: 1-3 months • Completion: When you’re in the painless habit of counting macros and/or calories, either per meal or per day, with most of your food choices being nutritious and balanced Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 165 Let’s go through each phase and describe what’s going on in a bit more detail. P h a se 1 : U n a t ta ch e d Ea t i ng Unattached eating is the first of the phases, and arguably the most important. The big problem that we’re trying to deal with here is fundamentally one of attachment to food. Yes, attachment in the Buddhist sense of the word, but also in the modern psychological sense. Too long in the hard dieting mode can start to paint food choices as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ as opposed to numbers. We become attached to eating ‘good’ foods in ‘good’ amounts at ‘good’ times, and avoiding all ’bad’ foods in ’bad’ amounts, at ’bad’ times. Instead of simply being an exercise in calculation, the eating process becomes one of fear of bad foods, salvation and guilt by cheat foods, and a whole lot of other emotions that are best kept to the religious scriptures and away from dieting. This giant emotional roller coaster is highly stressful, and it begins to take a toll of its own outside of the physiological toll of the restricted food intake. The issue here is that you’re too attached to food, to both its good and bad effects. You become addicted to its positive qualities and suffer by its negative qualities. You can imagine that this does not bode well for maintenance or balance phases and results in prolonged dieting. How do we bring this suffering and addiction to an end? The first step is to let the attachment to food recede altogether. The only truly effective way of doing this is to stop thinking about food. Now, there’s nothing wrong with thinking about food (or thinking, in general). But before we can exhibit positive ways of thought, we have to let the negative voices die down to a whisper. Stop thinking about food? How do you mean? We mean exactly that. For the duration of this phase, you eat only what you want, only when you want it REGARDLESS of what you want and when you want it. No more counting anything, including meals. No more guilt, no more deals with yourself, no more plans. What should you eat? We literally have no Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 166 advice for you. Whatever you want. Chances are that for the first while it will be what you’ve been craving. And that’s fine, enjoy! (It will be difficult, of course, to enjoy at first because of the psychological state that brought on your need for this phase, but eventually you will - and that’s good! It means progress is being made). For a lot of us that are very process- and perfection-oriented, this phase will be the biggest challenge. But remember, you don’t run this reset for fun… you do it because you’re at the end of your rope and the alternative is further suffering. You will likely gain some weight and some fat during this phase, but it will almost never be a huge amount, and the following months are sure to reverse the changes. During this entire phase (and in fact during every phase of this reset), you will NOT be using the scale. That’s right, no bodyweight measurements AT ALL during this whole reset. When you’re emotionally ready to make sense of the numbers on the scale, it will make its return into proper use, but for the whole reset, you’ll have no idea what you weigh and more importantly, you shouldn’t care. When you’re psychologically well, losing gained weight is super easy and straightforward. All of the science earlier in this book has given you the step by step guide. If you care about your weight during the reset, not only will you just be disappointed, you won’t accomplish the goal of the reset and it will have been largely in vain. Keep training and keep living your normal life during this phase, but don’t constrain your eating. How much should you eat? Enough to quell your hunger whenever it comes up! Don’t intentionally stuff yourself, but don’t deny yourself anything either. The more you let go and eat like a kid again, the better the chances that this needed reset will work and will get you back on track. This temporary eating style (which can get pretty interesting if you really let go) will NOT, we repeat, NOT “mess you up” and make you fat forever or anything else that your brain might be telling you. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 167 At some point, usually between 2 and 4 months into this phase, you’re going to get quite tired of just eating by your cravings. You’ll truly feel deep down that you’ve had your fill of all of your favorites several times over, and plans for the next tasty meal won’t be nearly as exciting as they used to be. You might even watch other people order salads or eat fruit and whole grains with lean protein and think “man, they must feel so good after eating that.” -Not morally good, but physically good. You know, the way fresh and healthy food makes you feel; light and free. Satiated, but not stuffed. You are likely to even begin to have cravings for healthy and lighter fare. All of your Instagram friends are posting about cookies, but you just want a cold, crisp apple! When you’re pretty much junkfooded out, it’s probably time for phase 2 to begin. P h a se 2 : N u t r i ti ou s Ch o i ce s After phase 1 has run its course, you’re going to be ready for some healthy and nutritious eating. After a diet has jaded you to the extreme, it’s certainly possible to subsist exclusively on dark chocolate ice cream and thin crust pizza for a week at a time. But after a while, you will start to feel the desire to eat well. Phase 2 is just that; beginning to eat well again. The goal of phase 2 is to begin to focus the core of your diet on nutritious choices. The great news is that this transition is very often going to feel completely natural, and in fact anticipated, after your phase 1 indulgences. Now, the very important idea as mentioned earlier is that you HAVE to indulge in phase 1, or else you’ll still want to eat mostly crappy craving food in phase 2. But if you really let go and indulged in phase 1, you’re very likely going to welcome phase 2 with open arms. What does making ‘nutritious choices’ mean, exactly? It means that when it’s not too inconvenient or driving you nuts, you choose the following foods for your meals: Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 168 • Foods that are minimally processed and preferably fresh • Foods high in protein such as lean meats and dairy products • Foods high in fiber and vitamins and minerals such as fresh fruits and veggies • Healthy fat sources such as nuts, natural nut butters, avocado, and olive oils Instead of having a burger, you get a whole grain burrito with brown rice and steak, with plenty of veggies. Instead of snacking on potato chips, you have fresh fruit. Instead of dipping your chicken fingers in ranch dressing, dip some carrots and celery in almond butter. By focusing on nutritious choices, you’ll be eating much healthier (which is good for you as soon as you start doing it) and you’ll be easing into the great habits that will serve you so well in formal dieting down the road. Do this easing in with no pressure. Just do your best to try to make healthy and nutritious choices, but don’t sweat it. If there’s a burger here and there, awesome. You DON’T have to be perfect, just choose, on average, more of the nutritious foods and less of the junk foods. One nearly instant benefit is that you’ll start to feel better. Eating well is going to make you feel lighter and more energetic, pretty much right away. Enjoy this phase for 2-3 months, until nutritious choices are pretty much automatic and especially stress-free. You’ll know you’re well on your way when you no longer harbor intense fears about controlling your food intake. You know that when placed in most any situation, you can, and usually do, choose to make nutritious choices, and that it’s ok if you don’t always make those choices. Once eating well is second nature again, you’ll likely be ready to begin phase 3. P h a se 3 : R ou g h M a cro s Coming out of phase 2, you’ll honestly be able to say that you have a pretty good relationship with food. Painfully restricting your own food intake seems in the Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 169 distance hazy past, and your outlook on eating is calm and optimistic. Every now and again you might panic a bit, but hey, we all do that! In phase 3, you’re going to make just a very small change to your eating habits. Over the course of 1-3 months of this phase, you’re going to get into the habit of getting most meals that you eat through the day to conform to a pattern. Here’s the pattern: • With EVERY meal where you can reasonably accommodate, you’ll try to get a good source of protein. We’re not gonna count anything yet, but a lean piece of meat about the size of 2/3 of your palm is a good place to start, or a protein drink or skim milk the size of an average coffee cup or medium glass. • In most meals that aren’t shakes or for which it’s not too inconvenient, you’ll try to have a large handful of mostly green veggies. What kinds? All kinds are fine, as are mushrooms, onions, tomatoes, and so on. • If you’re about to train within 3 hours or you’ve trained within 6 hours, you’ll add a small handful of whole grain carbs (brown rice, oats, whole grain pasta, sweet potato, etc…) or 1-2 pieces of fresh fruit to each meal. If not, you can either have about half that amount of these carb sources or none at all. • Based on how hungry you are, you can choose an amount of healthy fat from nuts, natural nut butters, avocado, or healthy oils like olive oil and possibly coconut oil. If you’re super hungry, finish your proteins, veggies and carbs first and then have whatever amount of healthy fats you want to get full. If you mix in your healthy fats, that’s fine too! If you’re not very hungry or have to train soon after the meal and don’t want to get nauseous, limit your intake of fats somewhat or altogether. As you follow these guidelines for most meals, most of the time, you’ll be establishing the habit of structure that’s going to be so very helpful for fueling you right away and for the dieting phases down the line. Once you’re in the habit of having lean proteins, veggies, healthy carbs and fats with most meals, you’ve pretty much made automatic some of the biggest difficulties people find with the dieting process. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 170 You can move onto phase 4 when you’re in the habit of getting in the correct (as described above) amounts of protein and the other foods with most every meal. As usual, a funky meal here and there is totally fine, but if most meals are balanced, and it doesn’t seem to you like a lot of work to be balanced, you’re well on your way and almost ready to kick butt again. P h a se 4 : Cou n t i ng & M e a s u r i ng After phase 3, you’re very likely to have re-established some very healthy and sustainable eating practices. You’re now eating mostly nutritious food, and doing so in balanced and structured multiple meals per day. The last step in this recovery process is to get you eased into the process of counting once again. You’re going to count only 3 aspects: protein, carbs, and fat. You’ll count them to the best of your ability (there are popular apps that can help greatly), and try to spread out their intake over the course of 4-6 balanced meals per day. THAT’S IT. No goal numbers, no crazy precision, no worrying… just count. You can eyeball food and you don’t have to weigh and measure everything, though you certainly can IF you feel comfortable and not anxious doing so. Get on the scale, record the number, and get off. If you’re the kind of person that needs SOME guidance on nutrient amounts, just follow the numbers you calculate from a maintenance diet earlier in this book. How do you get those numbers? Well, you’ll have to weigh yourself on your scale. Count up how much daily protein, carb, and fat content you’ll need and that’s it, shoot for those numbers. No worries, no nerves, no danger. \ Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 171 How closely should you follow the numbers if you chose to calculate them? Within 30g per day on all macros (protein, carbs, fats) is fine. That means if your weight implies you should eat 150g of protein but you ate 180, no worries! This way you can even count in your occasional junk foods and alcoholic drinks and not worry about a thing. Once you’re well into this phase, you’ll notice that counting and measuring food is not very complicated; neither physically nor emotionally. You just make nutritious choices, count up the numbers, eat great food, train hard, and enjoy life! You don’t have to be perfect, so just do your best! As you do these phases, please don’t rush. If you rush through them, you have wasted several months. By rushing, you get neither the impressive changes of a hard diet nor the psychological recovery you need. It’s like taking the afternoon off of work when you really need a week’s vacation; you don’t feel any more rested, and you’ve accumulated half a day of missed work to make up. The typical durations listed here are just recommendations for your expectations, not guidelines. If you need more time, take more time. Ultimately the “Completion” guidelines in the list of phases above are the only markers of progress and justification for moving forward to the next phase. If you’re not sure if you’ve met the completion guidelines, always err on the side of taking another few weeks in that same phase to decide. Mov i n g Fo r wa rd Once you’ve completed phase 4, and assuming you didn’t rush, you’ll very likely to have quite a different outlook on the dieting process as compared to the outlook you had when you began this recovery process. You’ll be looking at food with pleasure and anticipation, with an underlying sense of calm, and without desperation. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 172 When you’ve reached this point, you’re pretty much ready to pick a goal (fat loss, for example), set up your diet (or purchase your diet online or hire the services of a qualified diet coach), and calmly and willfully begin to execute the plan. Get in your meals, train hard, stick to the plan, do what it takes, and you’ll be much more likely to get the great results you want. Keep the diets goal oriented and follow the 2-3 month diet-to-maintenance structure, and you’ll be very likely to prevent another fall into unfortunate relationships with food and dieting in the future. S ta y i n g Mo t i va t e d Our motivations mostly come from our valued goals (how we want to look and perform) and our pride in meeting them. For most people, the right goals along with a logical and intelligent structure in achieving them (the scientific dieting process as described so far in this book) form the basis for a very strong motivation. But there are just a couple of strategies you can use to make sure that your motivation for dieting is as high as it can be. We’ve chosen the six we think are a must-mention, and described them below for your benefit. 1) Dieting for the Right Reasons 2) Shame and Accountability 3) Keeping Goals Realistic 4) Using the Food Palatability-Reward Hypothesis to your Advantage 5) Recognizing Progress 6) Health and Happiness Come First 1 ) D IET IN G FO R T H E R I G HT R E A S O NS When the calories get low and the scale starts to stall out a bit, motivation comes into play in a big way. At this point, the more of it you have, the better, and there’s no such thing as too much. Likewise, when you’re waking up a bit fluffier each week on your muscle gain diet… you’ll need all the motivation you can find in order to push on and make it through. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 173 The single most important factor in motivation is having valued goals. Put another way, you’ve gotta be dieting for some end-goal you actually want, and not just dieting with no end in sight. When times get tough, there needs to be a bright beacon on the horizon to lead you along on your path. How bright the beacon is depends on how good your reason for dieting is. The better the reason is FOR YOU, the more likely that you’ll see this beacon in storm after storm and stay the course. Are you dieting for the right reasons? There are many reasons to diet, and they fall into 3 categories: Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 174 • Bad reasons for pretty much everyone • Good reasons for some people that are not good reasons for you • Good reasons for you The “bad reasons for most’ category includes dieting to make someone else happy (a former, current, or future significant other or lover), dieting because you hate the body you’re in, dieting because you think a lean or muscular physique will make you MUCH happier, dieting out of spite “for the haters,” and about a million other reasons. The two biggest commonalities between all of the bad reasons to diet are that they come from a negative emotional place (running from something about yourself) and/or that they come with expectations of a radical quality of life and happiness change. Dieting out of negative emotional reasons will drain you like nothing else. Even if you achieve your goals, you’ll look back and see not much but pain, and you’ll look forward and see not much but emptiness. Dieting out of an expectation of enormous benefits can be done once, but pretty much only once. You’ll never do two diets for the purpose of a new and happy life because the first diet will make it crystal clear to you that not much changes other than your weight. Are we going to sit here and tell you that being leaner and more muscular won’t make you ANY happier? Absolutely not. We’re all adults and we’re not here to prop up frail teenage self-esteems. Being leaner and more muscular can make you feel better, let you fit better into the clothes you love, and bring you mostly extra positive attention from the opposite and same sex. That is all great, but overall, your general life happiness relies on a great deal more than looking hot in yoga pants. It helps at the margins, but only at the margins. You get used to how your lean body feels, new clothes lose their appeal, and compliments from people other than the ones you deeply love and respect don’t mean much after just Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 175 a short while. Happy people come in all shapes and sizes, and the biggest factors in happiness (genetic predispositions, having a career you love, and surrounding yourself with the intimate relationships that make you the happiest) have little to do with your appearance or fitness level. If you’re dieting because you think your life will be a totally unrecognizable and wonderful state once your goals are reached, you’ll be in for a rude awakening when your diet ends. Alright, so we don’t want to diet for the bad reasons, but there are in fact plenty of good reasons to diet. Some good reasons include: • Slight increase in baseline happiness above your current level • The pleasure of the deep perseverance it takes to accomplish your fitness goals • The self-actualizing experience of inhabiting the body YOU built • The pleasure of the journey and end-goal of fitness • Enhancing your health • The aesthetic pursuit of turning your body into a magnificent piece of art Those are all very good reasons, and to be sure, there are countless more. The very important point we are making here is that you should diet for the reasons in that list or otherwise – reasons that are good reasons for YOU. Sure, many people like to commit themselves to diet because just the process brings order to their lives. That might not be enough for you. You might find inspiration and motivation in toiling in obscurity to engineer your best; a physique or performance that will stun and engender awe, most importantly your own. If you choose the reason that is meaningful to you, it can and will help greatly in motivating you through even some of the toughest of times. When calories are being cut or your jeans are getting tighter and the training feels like it’s killing you slowly, your own personal good reasons for dieting will be what carry you through. Not the bad reasons, and certainly not someone else’s good reasons. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 176 Thus any time you begin a diet, or if you’re reading this during a diet, ask yourself just two simple questions: “Why am I dieting,” and “Will this make me happy?” The rest is easy to figure out. 2 ) S H A ME AN D AC C OU NTA B I LI T Y It is currently accepted and even applauded for women to be strong, athletic, and involved in sports. This is, sadly, a relatively new aspect of Western society. Nonetheless it is here now, so we should enjoy. With this has come what we would like to call an improvement in beauty ideals. Of course, as we have mentioned in this book already, it is healthiest to set your own standard of beauty, have it depend on your capabilities in addition to your appearance, and most importantly, be based on YOUR preference alone. That being said, none of us is entirely immune to wanting to achieve something resembling current beauty standards; its natural. Luckily, for the 21st century woman, those standards no longer involve Twiggy or anorexic looking ideals. Current standards of beauty are much healthier, and involve muscles and curves. Achieving this generally also means achieving good health and great performance in physical activities, so who could argue that it is terrible to work towards this ideal in a healthy, balanced manner? There is another issue though. It is very common, especially for women who have tried fad diet after fad diet and failed, to feel ashamed to try yet another diet. There is pressure for them to accept themselves the way they are, even if their current state is physically unhealthy. This shame and fear of falling off another wagon leads women to HIDE the fact that they are trying to lose fat. This presents a huge problem. The woman who is hiding her diet will have trouble sticking to it in front of friends and family, leading to cheat meals and inconsistency and an ironically higher likelihood of failure. Hiding your diet presents another issue. You lose the accountability factor of having supportive friends and family nudge you or remind you of your goals. If you have healthy, Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 177 reasonable weight management goals, the people in your life should be supportive and act as a great tool to help you stay on track and progress. If they are not, perhaps it is your friends you should consider losing before those pounds! In any case, if you are conducting your body composition changes in a healthy, well informed manner with healthy, personally derived goals, you should not feel any shame. The more supportive people you tell about it, the more you will feel motivated to be consistent and succeed. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 178 3 ) K EEP IN G GOA L S R E A LI S TI C All goals can be split into 4 basic categories: a. Goals that are so easy you can get them done no problem b. Goals that are challenging, but possible to accomplish c. Goals that are incredibly unlikely d. Goals that are almost certainly impossible Goals in category a. are not worth your time. In fact, you might not even accomplish them if you try, because they are so easy you’ll get bored before you do. If your goal is to lose 1lb per week for 1 week and then stop, you might as well stop before you start. If high motivation is something you’re after, category a. goals are not going to work. Goals in category b. are where most of your goals should lie. They are within the realm of possibility and even likelihood, but they don’t require you to quit your day job or accept an outside chance of accomplishing them. Losing 15lbs in 12 weeks is a challenging goal for a 160lb woman, but it’s not impossible. It will require lots of work and focused effort, but it can and very likely will be done if you do what it takes. Category c. goals are ok to make every now and again, but they should be optional secondary goals. They are so tough that while they are possible, often they won’t bear fruit. Winning your first ever figure or physique show is certainly not impossible. But when you show up for the first time, you’ll meet competitors often 10 years older than you… with 15 more years of training. These women have been taking 2nd and 3rd at shows for the last five years. They’ve put so much effort into their prep that trying that level of sacrifice on your first run is likely to overwhelm you and make you quit the sport. Should you give up on winning Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 179 your first powerlifting meet, CrossFit competition, or strongwoman show for those reasons? No, but your primary goal should be to do as well as you can, and maybe your secondary goal, the one you don’t think about too much, can be to win the whole damn thing. Also keep in mind - does anyone (aside from maybe sport historians) even care how you placed at your first show? Not even by a long shot. It’s how steadily you can improve that most determines how great you can become. If the advice for category c. goals is largely to avoid them or make them secondary, the advice for category d. goals is to abstain from making them completely. If you start out at 345lbs and your goal is to be a fit, healthy and happy sustainable 100lbs, you should re-think your goals. Almost no one who can comfortably stay around 100lbs without being chronically hungry and out of energy even has the genetics to gain an extra 245lbs. Yes, yes, we all think we can gain an infinity of pounds if we were only to eat enough dark chocolate almond butter and pizza, but after less than 100lbs gained, most people simply won’t be able to keep up the sheer daily calories is takes to get that big. If you do find yourself at 345lbs, then you almost certainly have the genetics to be larger than 100 lbs at a healthy weight. Now, do you have to stay at 345lbs? Certainly not. You can choose to be much lighter. A realistic goal of a long term (3-5 years from first diet start) stable 190lbs is within the distant reach of many 345lb’ers. Now, 190 isn’t your average Italian fashion model, but with the muscle mass you’re sure to put on during proper training on your fitness journey, you can look, feel and be in very, very good shape. Shape that both makes you a performance machine in the gym, and in competition, and one that gives you the sexy curves most people can’t walk by without double-taking. Unfortunately, Hollywood and social media are often of little help in setting up realistic goal choices. Almost every viral post and every inspirational movie or documentary is about someone who did the damn-near impossible. And that gets Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 180 many of us thinking; what if we can do the near-impossible too? To counter this perspective, it’s useful to look at your body as an investment (we’ll pretend this is just a perspective… in fact it’s reality). When you invest your finances properly, you do it with a great deal of care. You make sure to find the investments that carry the biggest payoff, and ones that are still not very risky. In this analogy, choosing a category d. goal is like taking your last 5 years of savings and heading down to the local casino to bet it all on red 11. If you want to most likely squander a ton of effort and almost guarantee disappointment, category d. goals are right up your alley. Stick to mostly category b. goals and you’ll slowly build a physique and performance level over longer periods that may allow you to achieve goals that would have initially been in category c or even d. But you don’t get to such results with one big 15-year plan of a goal… you get there with many category b. goals in a row that each take weeks and months at a time to fulfil. 4 ) USIN G T H E F O O D PA L ATA B I LI T Y -R E WA R D HY P OTHE S I S (F PRH) TO YO U R ADVA N TAGE What is the FPRH? FPRH is actually quite easy to define in simple terms, even with such an intimidating name. In essence, the FPRH claims that the more tasty the food you’re eating, the more of it you’re going to be able to eat at any one time and the more of it you’ll crave later. In addition, high volume and low calorie foods that tend to be less indulgently tasty (like veggies and fruits) are much more filling than processed and energy-dense foods like that tend to be more tempting. For a detailed definition and in-depth information on the FPRH, please see here, and for an academic discussion, here. The reality of the FPRH leaves us with both good and bad news, and some choices as to how to make things easier on ourselves during dieting. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 181 How can you use FPRH to your advantage, to make dieting easier and less demotivating? Because foods that don’t taste amazing don’t lead to nearly as many cravings as the tasty ones, it’s a good idea for many to restrict the percent of tasty foods they eat the deeper they get into a fat loss diet. Less tasty foods, on average, mean fewer cravings, and combined with eating filling, high volume foods, can lead to a much easier diet. Do you scarf down all of your food towards the end of a fat loss phase? Do you look forward to eating any time you’re not eating? The FPRH can make these nuisances much less powerful. It’s gonna take you a whole lot of chewing to get through a salad with dry chicken than a sautéed and juicy chicken breast, while both have identical calories. The high volume of food will fill you up more and for longer, and the next time you’ll have to eat, things won’t be nearly as exciting and your cravings will be much lower. I mean, who the hell craves dry chicken breast that much?! When your food is more filling and not a culinary whirlwind of taste, it starts to be more of a chore to eat and isn’t something you look forward to as much. Sounds pretty bad, but it’s a blessing in disguise when you are cutting. Because food is slowly being reduced on a fat loss diet, you can count on two things; less of it than you would like at any one time and less and less of it with each passing period of several weeks. Is it a good idea to take pleasure from and attach your emotions to something that is so rare and so in decline? If you focus on high volume foods (lots of fiber and water… usually fresh fruits and veggies) that are not the fat and sugar-laden treats you’d usually crave, your cravings actually subside considerably and you can use your mind for the dozens of other things you’d rather be thinking about during the day. This last point brings up some potential problems with a special category of tasty meal: the cheat meal. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 182 Why are occasional cheats meals often a bad idea on a hard diet? While some people handle giant cheat meals just fine, many are better off without them during a fat loss diet. “Cheat meals” or “free meals” are programmed intakes of food in which you’re basically allowed to eat whatever you want, which usually means super-tasty food like pizza, burgers, ice cream, etc. When many people eat their cheat meal, they greatly enjoy the experience. The next day or even later that day, however, they have to go back to bland diet food, and much less of it. Once back on their diet, they will notice that they crave more cheat foods. Tasty food is addicting! Not necessarily in any really bad way like drug addiction, but in the sense that the more you get (to a point), the more you want. Now, “to a point” is important to note as getting enough cheat meals (like on the diet reset program in the last section) goes a long way to making you no longer want to cheat. But the big problem is, on a hypocaloric fat loss diet you, by definition, don’t ever reach that point. If you ate enough cheat meals on your diet to be satiated, you would be eating so many that you wouldn’t be hypocaloric and no fat loss would even occur. So if you’re eating a cheat meal a week, you’re not eating enough to really squash any cravings. In fact, you’re basically engineering even more cravings by giving yourself just enough of the good life to stay addicted. When various intelligence agencies teach their staff how to extract information from captured spies, they don’t just teach them to beat, deprive, and torture the captives. They do something much more effective; they teach them to do plenty of the deprivation and torture, followed by a restful night’s sleep or a good meal in exchange for even the slightest bit of cooperation by the spy. Every time the spy cooperates even a bit, they reward him/her with a bit of the good life. Not enough of the good life to satiate, but just enough to create further cravings. After some weeks, most spies will have an incredibly hard time resisting an offer to give up important information. Their cravings for the good life and their behavior of looking forward to the next release are incredibly powerful. This is human psychology. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 183 If you have the choice, why do this to yourself? You can spend a big chunk of your fat loss diet hating every minute of it as your mind looks only forward to the upcoming cheat meal. You can scarf down the cheat meal knowing that every bite brings you closer to the much longer period of deprivation that is to follow. After a while, the whole experience can be miserable. If you use the FPRH and make your food voluminous and mostly lacking in taste (sugars, fats, spices, sauces…) and you stay away from cheat meals, you’ll see food much more as fuel and you won’t tragically hinge your happiness on this dwindling resource. Does this idea apply to literally everyone? No. Do you have to give up all tasty foods as soon as you start dieting? No way. But if you start getting cravings, and find that looking forward to your foods starts to make you a bit more miserable than you’d like, give the low-palatability foods a try. You can always go back to tasty foods if it doesn’t work out after a couple of weeks! 5 ) REC O GN IZ IN G P R O G R E S S Pride, one of the seven deadly sins of antiquity. Is pride really a sin? Certainly, pride can be taken too far. In the world of diet results, getting too big of a head about your progress can lead to more slip-ups. You look in the mirror and say “woah, I’m super lean!” Later that day your friends invite you to the Chinese allyou-can-eat buffet, and you think, “well, being that I’m in great shape already, why not?” You end up doing this more than once during a diet and you don’t lose as much fat as you had planned. If only you had managed to stay humble! While keeping your pride in check is a good thing, going too far on the other end of the spectrum can be a bad thing as well. Some fitness folks (and most of us will know a few of these people off hand) don’t recognize and bask in their accomplishments enough or even at all. Some of the best powerlifters in the world will respond to sincere complements with “I ain’t shit.” If you get rowdy and press them a little as to what they could possibly mean by that, some of them will insist that because they are not “the best,” then they’ve got no right to be proud. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 184 Well, even those who are the best at any given time are not the greatest of all time. And even the greatest of all time might just be biding their time… the great champion that will eclipse their streak of dominance might already be training, and winning, somewhere in the world of fitness. If you’re not willing to admit even to yourself how far you’ve come, what the hell is the purpose of training and dieting? Seriously. If you’re training and dieting in the search for self-actualization and a sense of accomplishment, how are you supposed to succeed if you’re not going to allow yourself to feel accomplished? You don’t have to pat yourself on the back Stuart Smalley style every time you have a productive day of diet. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 185 If you survive a hard weekend of tempting food and drinks without swerving, admit it — you’re a fucking warrior! After accomplishing muscle gain and or fat loss, women often line up those before and after pictures and post on Instagram – the place where all great success is highlighted. This can be a fantastic way for you to celebrate your achievement and inspire others. It can be a healthy means of self-reward. On the other end of the spectrum, it can be a tool for some women to generate self-approval via the approval of others. When you embark on your fitness journey, it is best for your overall happiness that the journey and the outcome occur to make YOU happy. If you are putting in hard work solely for the approval of others, you will enjoy the flood of likes and compliments in response to your progress pic, but as the posting day gets farther away, and the excitement of the attention fades, you will be left with how you actually feel about yourself. Before you post your pic, pause and ask yourself if you are doing so for healthy reasons. You SHOULD be proud and you SHOULD be able to share your success with others, but only if it is your personal success, not if the expected approval defines your success. If you recognize only progress that’s impressive to YOU and mentally reward yourself for it, you’ll only reinforce your desire to succeed; you’ll get that much mentally stronger and become even more motivated for harder and more productive dieting down the road. As with many (but not all) things, the middle road seems to be a good starting point for recognizing your own progress and complimenting yourself. Right between too much coddling and not enough credit is where you usually want to be. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 186 6 ) H EA LT H AN D H A P P I NE S S C O M E F I R S T In our fitness journeys, we sometimes get so caught up in our goals of progress that we get all of our priorities out of whack. Sometimes we’re not even sure what steps took us to thinking this way, but we want those abs to come out more than we want anything else in the world. And we sometimes start acting like it. We push aside our healthy relationships, we start dieting to the extreme and training more than we can recover from, and we might even mess with some drugs without proper knowledge or consideration of side effects. Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 187 Unless you’ve been kidnapped by terrorists and forced to get into contest shape to save your family, you’ve got to keep two ideas in the back of your mind at all times in your fitness journey. The first idea is that this journey is voluntary. It’s a choice, every hour, day, week, month and year as to how much time and energy you want to put into this. If your training and dieting is making you miserable with no end in sight, remember that you are the only person pushing yourself. That’s it. You can change course any time you like. Of course you don’t want to change course compulsively and mess up a good plan, but if your plan is bad and not making you happy in at least the long term, rethinking your approach is always and everywhere YOUR choice. Secondly, this journey is about health and happiness. You may have to work longer hours than you want so that you can keep your job and provide for your family. You may have to take care of other people simply because they’re related to you and can’t care for themselves, even if your relationship with them has long been sour or was never good to begin with. That’s stuff you HAVE to do in some sense. This fitness journey? It’s just to keep you healthy and make you happy! Can you restrict your body too much for short periods and be miserable during that time so that you can be happier in the long term? You bet, and that’s a reality of dieting. But if the whole process and even the destination isn’t making you BOTH healthier and happier, why are you doing this? If you’re reading this right now and can’t answer that question for your own fitness journey, some deep thinking might be in order. The only question to ask yourself is: Does the benefit of these goals outweigh the costs in discomfort? Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 188 Getting ripped is not mandatory. Having abs is not mandatory. Weighing 132 is not mandatory. All of these things are voluntary goals that only YOU can make. They all require some bit of discomfort to attain. You’re a healthy, beautiful and valuable person to yourself and to many others. You never NEED to get ripped or ultra-strong, so please, make sure it’s worth it to you. Because if it’s not worth it to you, it’s not worth it to the only person that matters. References FOOD PAL ATAB IL IT Y • The case for the Food Reward Hypothesis of Obesity, Part I • The case for the Food Reward Hypothesis of Obesity, Part II • Food Reward: Approaching a scientific consensus • Effect of sensory perception of foods on appetite and food intake: a review of studies on humans PSYC H O LO GY O F W EI G HT LO S S • Self-set dieting rules: adherence and prediction of weight loss success • Psychological symptoms in individuals successful at long term maintenance of weight loss • The Sporting Body: Body Image and Eating Disorder Symptomatology Among Female Athletes from Leanness Focused and Nonleanness Focused Sports • Long term weight loss maintenance Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 189 • Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain • Is your brain to blame for weight regain? Chapter Five F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 190 P. 1 9 1 06 Female Health Issues Across the Lifespan This chapter will go over some aspects of nutrition across the female lifespan, including dietary needs of teenaged girls and pregnant and nursing mothers. It will also cover disordered eating and its detrimental effect on health. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 191 Chapter Six Nutrition for Children & Teens While this is a diet book for females, half of all children and teens are female, and many of the women reading this are mothers themselves. For your benefit, we’ve included a short discussion of the basics on child and teen nutrition. The following are some of the more pertinent points, often bulleted and listed for your ease of reading. One of the biggest insights on nutritional approaches for children and teens (unlike those of adults), is the recommendation to avoid focusing on bodyweight as the central outcome measure and data point for progress tracking. As opposed to focusing on weight (which can lead to poor physical development, poor body image, declining food relationships, and damage to parent-child relationships), focusing on healthy eating for better nourishment and strong athletic and academic performance is paramount. Children have a much higher weight variability during their developmental years than they do as adults. Thus, an adult of healthy weight will often have previously been a child of both lower and higher weight compared to her peers as she grew up through the various developmental stages of childhood. It seems better for parents to gently encourage healthy eating practices (and lead by example) rather than focusing on a child or teen’s weight at a particular time during their development. As children grow and make healthy choices, their weight will most often normalize to the healthy range. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 192 Many of the same rules of healthy eating that apply to adults apply to children as well. Average meals should be eaten every 3-6 hours (or at longer intervals with healthy snacks in between), with most meals containing a base of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean meats. High intakes of sugar and saturated fats should be limited within the general approach to the diet, but balance is critical for both physiological and psychological development. Fast food and junk are totally ok for kids to eat every now and again, so long as MOST of their meals are composed of healthier options Calories should be targeted towards hunger and not strictly controlled in most circumstances, and macronutrients need to be relatively evenly distributed between protein, carbs and fats. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 193 Carbs: Most children of all ages should consume between 45% and 60% of their calories as carbs. This of course means that low-carb diets are almost exclusively out of the question for children and teens. Carbs are the most important fuel for both the highly active nature of childhood and the developing brain (especially for academic abilities). Fats: For children between 1 and 3 years of age, fats should compose between 30% and 40% of the diet, including plenty of saturated fats for growth and development. For children and teens between 4 and 18 years of age, fats should compose between 25% and 35% of total calories. Protein: For young children (under age 10), protein can compose between 10% and 20% of calories, and that upper limit can go as high as 30% for older children and teens. The lower intake of protein for younger children isn’t so much a health concern (extra protein is not toxic), but is lower to make more room in the diet for the fats and carbs they need. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 194 If you’re interested in more diet information for your child or teen, MyPlate.gov is an excellent resource for age-specific nutritional information. The Female Athlete Triad & Bone Loss With the likely unintentional but unfortunate acronym of “FAT,” the Female Athlete Triad is a relatively uncommon but deleterious condition that can affect some women in the fitness community, and especially those that take hypocaloric dieting and high volume training too far. The FAT is based on the low end of a continuum of the following: • Energy Intake (low calorie intake) • Menstrual Function (intermittent menstrual function or lack of menses) • Bone Mineral Density (low density) Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 195 In a situation of complete health, energy intake is high enough to sustain all normal sport and reproductive function, menstruation occurs normally, and bone mineral density (BMD) is within the normal range. This situation places the athlete completely out of the FAT spectrum. On the other hand, the worst case scenario is when all of the negatives line up, and have been lining up for long enough to do serious damage, especially to BDM. Thus, in the worst case of FAT, an athlete displays chronically low energy intake (not enough to support athletic and reproductive functions for months and years at a time), they no longer have menstrual cycles (hypothalamic amenorrhea), and they have developed osteoporosis largely because of the previous two factors over months and years. Most fitness females will not meet the criteria for full-effect FAT, but many can have some of the components. This is especially true for distinct durations during hypocaloric dieting that gets a woman below roughly 15% body fat. So what does bodyweight have to do with it? In essence, when hypocaloric dieting is pronounced and longer term, or if the female becomes very lean (usually below 15% body fat) and stays there, the reproductive system can essentially pause most of its functions. The evolutionary logic for this is very straightforward. Your body basically makes the calculation that you are in a starvation environment, or in an environment in which you’re not getting in enough calories to bear children. Thus, it shuts down menstrual production so that energy can be used more for survival and less for reproduction. When times are good again (sufficient food intake is present), your menstrual systems becomes active once again and normal hormonal and reproductive activities resume. So far that sounds pretty innocuous, and it would be if not for associated hormonal production. The big problem arises because the female reproductive system activity supports estrogen production. Once reproductive activity slows or largely shuts down, estrogen production goes with it. Estrogen is a very Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 196 big player in bone growth and repair. Bones are composed of living cells and inorganic minerals in a united complex. The whole complex is under a constant state of flux, being degraded and rebuilt all of the time. Estrogen is an important hormone that signals bone growth and repair to occur, largely through its effects on the Osteoblasts, which are the bone-building cells of the body. Once estrogen is greatly lowered, bone growth and repair slows significantly. Since bone breakdown and turnover is always occurring, the net result of low estrogen can mean chronic bone loss. Not in days or week or months, but years. Taken together, the process of FAT expression occurs in the following way in worst case scenarios: a. Chronic hypocaloric dieting occurs, especially without maintenance phases used to re-establish metabolism OR body fat is chronically kept well under 15% or so. b. M enstrual cycles are interrupted and become intermittent or cease altogether, lowering estrogen production for long periods at a time c. C hronic low estrogen levels AND the low calories which have in part caused them to contribute to bone loss (calories and the nutrients foods carry, such as calcium, also play a large role in bone dynamics) Does it always happen in this precise of a pattern? No, and here are some of the reasons why it might not. • Most females will not diet so hard and for so long so as to accumulate enough periods of amenorrhea (lack of menses) to make a big dent in lifetime menstruation times • Most females will not remain in a sub-15% body fat environment for extended periods of time • Many females will not have genetics that put them at serious risk of bone loss even with common amenorrhea Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 197 • Many females will only notice the symptoms of bone loss much later in life (55+) due to the sheer time that bone loss must occur in many cases before it becomes full-blown osteoporosis Even still, most women are at some risk for osteoporosis at some point in their lives, and this is not good news. The porous and brittle bones of osteoporosis fracture easily, even under the strain of normally active muscles. In its more serious incantations, osteoporosis can make even mildly strenuous daily tasks a huge risk for bone fracture, and can render an otherwise healthy individual mostly inactive. The news about osteoporosis gets a bit worse before it gets better. It turns out that most research indicates that the bone loss that leads (first to osteopenia and then osteoporosis) is not reversible. That is, even if the causative factors of bone loss are eliminated, there doesn’t seem to be much we can do to re-build what was lost, if at all. So with bone loss, what you have is what you’re stuck with, and in reality, most measures to fight bone loss are just able to slow it down, not stop or reverse it. This means that if you have good genetics for bone mass and you take good care of yourself most of your life and avoid conditions such as those of FAT, you might be on track to develop debilitating osteoporosis only by 140 years old. Since you’re unlikely to make it to that age for a host of other reasons, you may not ever see osteoporosis in your lifetime. On the other hand, most of us have to deal with the reality of likely living long enough to see osteoporosis. Most women in the U.S., especially those of Caucasian and Asian ancestry, will have some osteopenia in their late years and many will suffer from osteoporosis as well. Because most of us will eventually develop osteoporosis, and because bone loss is not currently possible to reverse on any large scale, it’s likely a very good idea to do something about preventing as much bone loss as possible for as long as possible. Which means that if you’re reading this, possibly starting right now! But what to do? Here’s a list of the most effective strategies: Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 198 • Avoid prolonged periods of hypocaloric dieting. Following our advice of 3 months maximum before maintenance phases should be a great start. • When dieting, don’t allow greater than a 1000 calorie per day deficit. A 1000 calorie per day deficit roughly translates into a 2lb per week rate of weight loss, which for most women is faster than the earlier guideline of 1% anyway. • If you have to be at body fat levels of under 15% (or lower than that), try to only be that low in body weight for the time that you need to be. Staying very lean after a figure show is great for your ego, but might not be the greatest for your long term health. Though if your figure body fat is around 10% and you weigh around 150lbs, just 15lbs or so separates you from contest body fat and 20% fat, which is lean yet healthy. A 15lb drop during a 12 week diet prep is a breeze in most cases, so as this advice is quite realistic without much hassle. • Expect to have normal menstruation during most of the year, with spotty or missing activity during very hard endings of diets or very lean body compositions that are inherently temporary. If you haven’t had a period in over 3 months at a time, it’s a good idea to evaluate your diet and training goals. • Manage fatigue in your training plan. Train hard but sustainably, with planned recovery workouts, rest days, deloads, and active rest periods. • Consume a diet high in vitamins and minerals, especially calcium. Calcium is a component of bone construction and is found in abundance in dairy. If you’re not getting enough calcium per day (at least 1200mg per day) and you’re having trouble getting enough from food, a supplement may help. The good news is that most whey and casein powders are rich in calcium. • Continue to train hard and heavy. Running, jumping, tumbling, and heavy weight training literally stimulates bone growth and preservation. Because bone loss mostly occurs after age 30 and bone growth is possible until 30, training heavy at all adult ages can both add bone density for later (before age 30) and greatly slow bone loss (after age 30). If too much hypocaloric dieting or hard training occurs at younger ages, late menarche (onset of menstruation) may result. Late menarche is defined as the occurrence of the female’s first period after age 16. This is a big problem, as it is linked to a huge miss in opportunity for bone building in the teen years and is greatly associated with osteoporosis later in life. If you’re younger or you’ve got young female children, late menarche is definitely something to watch out for. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 199 Disordered Eating Eating disorders are a very big deal. Every year, numerous women (who are at vastly greater risk for eating disorders compared to men) literally die from eating disorders gone too far. Because eating disorders are in almost every case psychologically caused, the best we can do is recommend that you see a psychologist or psychiatrist if you feel you could be at high risk for disordered eating. Below we will outline some of the basics of common eating disorders, but we greatly urge you to seek professional guidance if you catch many of the signs in yourself (or direct a friend to professional help if she seems to be at risk) instead of trying to deal with the problem yourself or, worse, hiding the issue. There are three categories of disordered eating that are of pertinence to us here, and they are ordered by seriousness of health and life risk to the female: • Anorexia Nervosa • Bulimia Nervosa • Anorexia Athletica Anorexia Nervosa is far and away the most serious eating disorder that affects females (in fact, which affects either gender). The most fundamental feature of anorexia is food avoidance; willfully trying to eat much less than is either necessary to safely and effectively lose weight. Though Anorexia mostly affects non-athletes, those athletes that are in sports which emphasize lean physiques (gymnastics, endurance sports) tend to have higher numbers of anorexic athletes than sports in which lean physiques are not quite as prized (basketball, volleyball). The critical component of anorexia is that it is primarily (and many would argue Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 200 almost exclusively) a psychological condition. That is, the woman’s drive to lose more and more weight is not nearly as much related to sport performance or health as it is to an obsessive psychological condition. Though anyone of any size can be anorexic, those with a BMI at 17.5 or lower are considered at risk, because prolonged weight loss below that body size is actually life-threatening, and many people per year kill themselves via being underweight due to anorexia. If you suspect that you or someone you know has anorexia, DO NOT try to give them food advice or send them to a nutritionist. They are not simply confused about how to diet, and accidentally eating to lose weight through their errors… they are willfully trying to get as small as possible with almost total disregard for any negative repercussions. Anorexics should only be referred to psychologists, psychiatrists, or medical doctors (the latter of whom will refer to the former two professionals). Bulimia Nervosa is a disorder related to anorexia, but unlike the food avoidance that constitutes the central feature of anorexia, bulimia is characterized primarily by purging behaviors. Many bulimics will eat a relatively normal diet, but will purge some of their meals in one of several ways, including vomiting and laxative use. A third lesser recognized bulimic purging method is exercise, usually in great excess. Thus, eating a pizza and then going on a 1000 calorie cardio binge right after can be considered a bulimic and thus disordered behavior. Unlike anorexia, in which low bodyweight is both a telltale sign and a serious concern, bulimics are not always underweight. Unfortunately, they can still do serious health damage by missing out on nutrients from the food they purged, overtraining due to exercise addiction, or causing damage to their esophageal and oral tissue (teeth included) via excessive vomiting. Just as with anorexia, bulimics should best be referred to psychological and psychiatric professionals and not nutritionists. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 201 The last category of common female eating disorders is a controversial one. Anorexia Athletica is different from Anorexia Nervosa in that those exhibiting it are losing weight for a distinct and logical sport-related purpose. Though their end-goal is logical and usually healthy and safe, the obsession with their weight, body shape, and food that they can display sometimes ranges into the disordered spectrum. Sometimes, the kinds of obsessive tendencies, body relationships, and eating habits that an athlete develops during their competition phases can carry over to the rest of her life and present as Anorexia Nervosa, with the discussed serious consequences. The reason that the diagnosis and even term of anorexia athletica is controversial is that very rarely do weight-controlling athletes that exhibit it turn into nervosaclass anorexics. In fact, the vast majority of athletes that exhibit anorexia athletica normalize their weight in the offseason and/or upon retirement. It’s not quite clear whether the weight control sport and dieting practices helped to cause the later anorexia nervosa, or that weight control sports simply attract more of the kind of people that are at risk of eventually developing anorexia nervosa in any case. With athletes that exhibit an obsession with eating, weight class, and exercise/ training, it’s best to make sure that the lines of communication are open and that positive food and body relationships are being emphasized. Athletes that express this condition should be monitored for warning signs of anorexia nervosa development (such as a dwindling commitment to their competition weight and a rising commitment to an ever-lowering weight). Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 202 Modifications & Expectations for Menstruation & Birth Control Sport performance changes in predictable ways during menstruation. On the whole, it’s not clear whether menstruation impairs peak performances. While it might, in some women, due to pain and fatigue, other women seem unaffected. In fact, some women report improved performances during menstruation, and the individual response variation seems very large. If you’re experiencing high fatigue levels during this process, your reaction time may also be impaired, and with it, your general athletic ability. If this is the case, you may want to take a few easier training days so as to reduce the unlikely, but slightly elevated chance of injury as a result of this disrupted coordination. If you’re one of the lucky ones that exhibits increased performance, the boost will usually occur in the immediate postmenstrual period. Some weight gain may occur for several days during the menstrual cycle, usually due to the effect of estrogen increases on the kidneys’ proclivity for water retention via the hormone ADH. This is a very transient effect, is selfcorrecting, and does not require any remediation on your part. All you have to do is remember that it’s water weight, stick to whatever plan you’ve been following, and watch the water weight come off just as easily as it came on. If you’re taking an oral contraceptive, some other predictable changes and responses may occur. Any recommendations regarding oral contraceptives are still in early stages, as the body of research on other methods is not sufficiently large and unanimous, such that we can draw any confident conclusions. While data on oral contraceptives and sport performance does exist, it’s important to mention that the study number and breadth is rather limited. The sample sizes (number of women who participated in each study) are not very high, and the individuals studied tended to be relatively untrained, which makes it difficult to Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 203 draw conclusions that apply to well-trained athletes. With all these limitations in mind, we can, however, draw some tentative conclusions: • Oral contraceptives do not appear to have a large impact on strength • Oral contraceptives may increase cardiac output, but this does not seem to increase VO2 Max, and thus may not improve performance • Max heart rate does not seem to be increased during contraceptive use • By decreasing menstrual blood loss, oral contraceptives may decrease the risk of iron deficiency • While some individuals experience some weight gain on oral contraceptives, many others do not experience this reaction Based on this, contraceptive choices are probably best made based on individual experience. If you personally experience weight gain or other effects not beneficial to your performance for your sport, a non-hormonal option might be best for you. In terms of dealing with menstruation with reference to competition, and dieting, tracking is a great idea. There are phone apps that can help you track and predict when you will be menstruating. Coupling this with your own tracking of body weight changes across your cycle and logging of perceptions of performance and fatigue around menstruation can help you anticipate the potential effect during competition preparation. For example, let’s say you are a 150 lb woman who fights in a combat sport with a mat side weigh in (recall from the earlier chapter that this type of weigh in does not allow for any water weight manipulation without sacrificing performance). Let’s say your next competition is in a month and your desired weight class is 140-150 lbs. If you know you gain two pounds of water weight before your period, and the weight doesn’t generally drop back off until the end of your period (which you know from tracking is on average 6 days long) and you see from your period tracker that you will be two days into your period at your competition, you can now plan for Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 204 this inconvenience in a simple and smart manner. You can do a quick diet over the next weeks to lose a couple pounds by the time of competition so that you don’t risk getting pushed into the next weight class or disqualified because of that predictable weight increase. Nutrition & Activity During Pregnancy Dieting during pregnancy is a very serious matter. If you do some horrible fad dieting (and we all have at some point or another) as an adult, almost all the negatives are reversible, and few of them are even acutely serious. However, during pregnancy you’re responsible for not only your own wellbeing but the wellbeing of another life. In fact, the way you eat during pregnancy can affect your child’s entire life. Scare tactics aside, you really have to mess up your diet for anything very serious to happen to the growth and development of your child. However, there are some important concepts and general recommendations to keep in mind to ensure the supply of nutrients to the fetus is nurturing and uninterrupted. Perhaps the most important take-home point of this section is that hypocaloric dieting during pregnancy SHOULD NOT OCCUR. Pregnancy is a time for supplying adequate nutrients to keep the baby developing on track and to keep yourself healthy and nourished, not a time for beach bodies. Weight SHOULD be gained during pregnancy in every case, and even those starting pregnancy in the obese weight range should look to gain (a little less weight than average maybe, but STILL gain). If you happen to be overweight or obese, the best course of action on weight gain recommendations is to speak to a healthcare professional (your doctor is source #1 in this case) to determine the proper amount of weight gain in your particular case. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 205 WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCY SHOULD ROUGHLY OCCUR AS FOLLOWS: • 3.5lbs during the first trimester • 1lb per week from the second trimester onwards to delivery • 25-35lbs over 9 months for a single baby • 35-45lbs for twins THE BREAKDOWN OF THE 2535LB AVERAGE WEIGHT GAIN IS, ROUGHLY: • 7.5 lbs: average baby’s weight • 7 lbs : extra stored protein, fat, and other nutrients • 4 lbs : extra blood • 4 lbs : additional body fluids • 2 lbs : increased breast size (woohoo for some of us!) • 2 lbs : increased size of uterus & supporting muscles • 2 lbs : amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus • 1.5 lbs: placenta Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 206 As you go through pregnancy and gain weight, calorie demands change. Within the first trimester, calorie intakes should not change noticeably. During the second trimester, calories should be roughly 350 higher per day than your pre-pregnancy intake, and they should increase to roughly 450 calories per day above baseline for the third trimester. This is fine advice if you want to use it to help design your weekly batch-cooked meals, but don’t take it as religion. Eating to hunger should always take precedence, even if that’s sometimes over or under the amount of recommended food. Other than adequate calories, a diverse and complete diet should be the goal during pregnancy. Whole grains, fruits and veggies, lean proteins and healthy fats should form the basis of your diet during all trimesters. Consuming plenty Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 207 of dairy as well and avoiding excessive sugars and trans- and saturated fats is also good advice. By eating a well-balanced diet as described above, you’ll be likely to get in all of the micronutrients you need during pregnancy. Here is a brief list of some of the more important nutrients of focus during this time: • Folic Acid • Reduces risk of neural tube defects • Goal: 600 mg/day • Available in: fortified cereals, breads and pastas, and folic acid supplements Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 208 • Iron • Most common nutrient deficiency during pregnancy • Can result in iron deficient anemia • Pica is a sign of iron deficiency (craving or consumption of non-food items like chalk or dirt) • Goal: 27 mg/day • Available in: Meat, fish, poultry, leafy greens, fortified cereals, and beans • Supplement if needed but absorption is lower than through food • Calcium • Allows for healthy development of fetal teeth, bones, heart, nerves, & muscles • Calcium will be leached from the mother’s bones if intake is not high enough → increases mother’s risk for osteopenia or osteoporosis • Goal: 1000 mg/day (3 servings of calcium rich food daily is a start) • Available in: Low fat/fat free dairy (milk, cheese yogurt), calcium fortified cereals & juices • Vitamin D enhances calcium absorption • Choline • Required for proper fetal brain development • Goal: 450mg/day • Found in many foods, but most pregnant women do not consume enough (may need to supplement) • Iodine • Required for fetal brain growth and development • Goal: 220 micrograms/day B e n e fi t s o f E xe rci s e du r i ng P re gna ncy Yes, pregnancy is a time for nourishment and care, but that does not mean you have to become sedentary. In fact, exercise during pregnancy is vastly considered to be a net-positive for many of the following reasons: • Improves circulation • Prevents painful & uncomfortable swelling • Improves efficiency of lymphatic system Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 209 • Enhances nutrient delivery to maternal and fetal tissues • Reduces overall discomfort • Low back pain • Edema in legs • Stiff joints • Constipation • Bloating • Insomnia • Significantly lowers risk of hyperglycemia • Reduces risk of gestational diabetes • Reduces excess weight gain during pregnancy • Reduces postpartum weight retention If you become pregnant, the best advice is to continue activity at a reduced intensity level, with the intensity reduction proportional to the time course of the pregnancy (intensity should fall as pregnancy proceeds). Frequent water breaks for adequate hydration are highly recommended, and the following should be avoided most of the time: • Exercising to fatigue • Maximal exertion or high intensity activity • Activity that has a high fall risk • Contact sports • Full sit-ups throughout pregnancy • Prone position exercises • Avoid supine position after 3rd month of pregnancy • Isometric contractions • Exercising in hot, humid environment Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 210 Speak with your healthcare professional before beginning any new exercise program when pregnant, and do your best to stay healthy, nourished and happy! N u t r i t i o n & Acti v i t y du r i ng B re a s t fe e ding Breastfeeding offers some special nutritional and activity recommendations of its own, presented here in a bulleted list for your convenience. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 211 Calories: • 670cal/day extra are required to generate milk when an infant is exclusively breastfed • Closer to 450 calories once the infant is 9 months old When dieting during breastfeeding: • No more than 500 calorie deficit daily • Resting metabolic rate (RMR) plus physical activity energy needs (from earlier chapters on calorie intakes) +670 calories for breastfeeding, minus 500 calories = recommended calories for weight loss • 670 calorie increase actually comes from an increased RMR since milk production is a continuous process • Moderate reduction in calories should not cause a decrease in milk production • Only lose 0.5-1.0lbs per week • True fat loss typically does not occur until 2 wks postpartum • Initial weight loss is fluid loss Protein needs: • 15-20g per day above normal/recommended intakes • 15g → Amount based on protein concentration of milk • 20g → based on nitrogen balance studies Carbs & Fats: • Same as peers (normal recommendations from earlier chapters) Physical activity during breastfeeding: • Usually not released to full activity for 6-8 weeks postpartum • Follow doctor’s recommendations regarding resistance activity • Moderate physical activity is recommended • Consult with your physician and agree on a plan for when you can begin or resume strenuous physical activity Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 212 Menopause Usually occurring between ages 45 and 55 for most women, menopause offers some special nutritional and physical activity recommendations of its own. Studies on the subject of menopause have revealed an average of 1lb gained per year by women over 55 years of age. While some of that is menopause related, some is due to other factors. Several of these other factors may be responsible for the average weight gain for older women, including: • Age-based decrease in Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) solely for genetic factors • Further decreases in RMR due to muscle loss • Gain due to decrease in physical activity • Gain due to disruption of normal sleeping patterns via shift work and other lifestyle factors that cause sleep deprivation • Improper size of meals (large portions) Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 213 Not only does weight gain occur after menopause, during menopause itself, some female body changes occur that on net balance may result in poorer health. As estrogen production declines, body fat stores can increase, but a redistribution of fat can also occur. During menopause, many women see a greater accumulation of intraabdominal fat (fat lining the organs, located under the abdominal muscles) as well as subcutaneous fat (fat under the skin… the floppy stuff) in the abdominal areas. At the same time, fat around the hips, thighs, and glutes tends to decline in amount. The result is the development of a more “android” (apple-like) shape from the usual and more typically feminine “gynoid” (pear-like) shape. The very hormonal changes that contribute to this redistribution also increase the risk for cardiovascular disease. Part of this change is due to a decrease in Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHGB), which can also lead to an increase in chances for insulin resistance. How do we combat such negative changes? A focus on high levels of activity and healthy eating are the best weapon by far. If you stay active through the years and continue to eat a diet high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats and healthy fats, most of the weight gain of menopause is much less likely to occur. Unfortunately, the perimenopause period (the time right before, during, and after menopause) comes with a slight increase of depression, which in some individuals can lead to an increased reliance on food for emotional support, as well as a decrease in physical activity. Of course, this additive effect of more eating and less activity (combined with hormonal changes of menopause) increases the risk for obesity. Obesity itself is very strongly correlated with depression, so the situation is nothing to sneeze at. This turn of events by no means affects everyone, and most women find a healthy balance and don’t so much as see a blip in their continued healthy lifestyle. However, being vigilant for the potential risks of this nature is likely Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 214 wise, especially for the woman about to enter menopause. If depression signs are detected, speaking to supportive family, friends, or healthcare professionals is almost always a good idea. As was discussed in the section on the Female Athlete Triad, lower levels of estrogen are associated with an increased risk of bone loss. Estrogen declines lead to the osteoblasts (bone-building cells) becoming less active and bone loss can increase in rate. Especially important at this time are sufficient intakes of calcium, vitamin D, phosphorus, and protein which are the main building blocks and helpers of bone building. A recommendation of at least 3 servings of calciumrich food per day is a good start for post-menopausal women, with lean dairy products topping the list of such foods. Vitamin D can be taken in by food and supplements, but it’s also synthesized by sunlight that hits your skin. If you don’t make it out to the sun much or live in relatively cloudier or less sun-drenched areas (much of the northern states of the U.S., most of the U.K. and Nordic countries), a vitamin D supplement is likely a wise choice. Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 215 References • The American College of Sports Medicine position stand: The female athlete triad • Choose MyPlate • Female Athlete Triad: Past, Present, and Future. • Understanding weight gain at menopause • Energy and protein requirements during lactation • Healthy Weight during Pregnancy • Exercise for Special Populations • Dietary reference intakes : the essential guide to nutrient requirements • Lifestyle interventions targeting body weight changes during the menopause transition: a systematic review • Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition Guidance for Healthy Children Ages 2 to 11 Years • Advising women on the menopause and diet • Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition and Lifestyle for a Healthy Pregnancy Outcome Chapter Six F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 216 P. 2 1 7 07 Female Challenges & Expectations Here we will discuss some of the social factors that play roles in women’s body image and motivation to make body composition changes. We hope this chapter will help you think about your goals and intentions when dieting and maintain a healthy outlook regarding your body and health. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 217 Chapter Seven Males diet and train just as hard as females do, but for multiple reasons, the female dieting landscape is fraught with unique challenges. For primarily sociological reasons, females are more apt to fall prey to a certain set of inefficient and negative assumptions and thought patterns. In this chapter, we’ll try to clear the way of what we see as some of the biggest informational and psychological challenges to dieting females. Starting Slow If you’re new to dieting or you’ve been bouncing around with some perhaps not-sosound dieting methods in the past, many of the scientific P 218 dieting approaches in this book may be brand new or relatively new to you. So, if you like the book so far and you’re convinced you want to make a change, what do you do? Just set up your whole diet, from calories through macros, timing, composition, and all the way down to supplements? That is certainly something that can work for those with some good prior dieting experience. For those just starting out, a simpler approach may be best. We know from general psychological principles that human cognition is a limited function… you can only have so many thoughts in any one time period. We also know that if you try to juggle too many priorities and overload those limitations on thought and concern, anxiety and worry tend to be a common result and can lead to dropping the ball on your overly complex plan. Thus, if the first thing you do when you begin your approach to scientific dieting is, well, everything, then you might quickly find yourself overwhelmed. Instead of jumping head-first into the scientific dieting world, a better idea might be to start with just one or two principles at a time until it’s second nature to you. This means that you’ll start with calorie balance first and maybe rough macronutrient amounts, then move along to the other principles when you’re well used to counting calories and eating an approximate amount of protein, fat and carbs. To ease in even slower, you can keep eating the same foods you’ve always been eating, regardless of macros, but for several weeks focus on controlling portion sizes to adjust the calories you’re taking in – so as to put yourself in a hypocaloric state. After a couple of weeks, controlling portion sizes and thus the calorie amounts of your daily intakes is pretty much second nature. Now you’re probably ready to start counting macros. Track the total daily protein, carbs, and fats you’re eating and do your best to hit your chosen goals for them. It’s gonna be a bit stressful at first, but no worries, within weeks it will seem like you’ve always counted macros Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 219 and calories. It helps to write down daily goals and amounts of macros you should have in each meal or use a tracking app. Because macros and calories combined account for roughly 80% of your diet’s effect, you can just stop right there and IIFYM (“If It Fits Your Macros” – a popular style of more loose, but effective dieting) yourself to success! Just as long as you eat plenty of healthy, nutrientdense foods (fruits and veggies), you’ll be well on your way to your fitness goals. If you’d like a bit of an edge, you can focus on nutrient timing once macro counting is second nature. And if you’re well used to all three of the most powerful principles, you can get into the nitty gritty of food composition and supplement use. The important message here: start slowly and make changes when you’re not feeling overwhelmed. There’s no rush to have the perfect diet right away, and the best news is that the first couple of principles are the most powerful by far, so that you know you’re starting at the place where you’ll be getting the most bang for your buck. As you get more and more practice, it WILL get easier and feel more like second nature. Then, adding other manipulations later will be less stressful. Ok, some of this seems obvious. Why are we even mentioning this? Far too many women have erred the wrong way in the past. We probably all know someone (perhaps even ourselves some time ago) that bit off more than she could chew with her first formal approach to dieting. Folks that do this tend to have very high failure rates, not because the diet is necessarily hard, but because it’s too much, too soon. You don’t jump into calculus in college for a reason; although it’s based on simpler mathematic principles, learning them all at once and understanding Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 220 how they are associated is overwhelming. You work your way up with important building blocks until it is easier to swallow. By spreading out the novelty, you can set yourself up for the kind of long term dieting success that has the power to make real body composition and performance changes. Realistic Paces of Change Almost all fitness media is filled with stories of rapid transformations. “30 day challenge made this woman a bikini model!.” Sounds great, right? DEFINITELY! ONLY THE TWO-FOLD CATCH OF SUCH A RAPID APPROACH IS: • How high is the risk of failure, unwanted side effects, and dropout from such a rapid approach? • How sustainable are the results after such a rapid approach? Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 221 These are NOT inconsequential questions. It turns out that extremely rapid bouts of dieting have a very high dropout rate and a very low sustainability rate. What’s the use of suffering through a crazy diet just to gain the weight back? Or worse, lose muscle and motivation for another diet AND then gain the weight back? For the multiple psychological and physiological reasons mentioned in the preceding chapters, a steadier and more sequenced (with maintenance phases interspersed) diet approach is likely to yield better results in the short and long term. Any rate far in excess of 1% bodyweight lost per week can lead to a much higher risk of falloff or rebound. Ok, so rapid dieting is really bad. Why not just avoid it in a big way and just eat healthier than you are now? No misery, no suffering, and no rebounds or falloffs! Right? This advice has been echoed numerous times in the anti-dieting camps. “All diets are bad” goes the advice. “Just eat well and have a healthy lifestyle and you’ll be in great shape.” Well, this is certainly great advice for a balance phase, but by definition, no weight is lost or gained in a balance phase. Since weight loss is the most powerful weapon to cut fat, this leaves us with a pretty big problem. It turns out that “healthy living” is just that, and doesn’t have much power to change your body composition or performance. In order to gain ground in these qualities, you’ve gotta diet with a purpose and make measurable changes, often to your bodyweight. Lastly, research has shown that the results of super slow rates of weight loss are actually less sustainable after the diet than results of faster rates. Why? Motivation is likely highly involved. Those who spend 3 months losing 5lbs are just not that pumped about their results. They might be more likely to go back to their old eating ways because they just were not that impressed with their results and 5 pounds comes back a lot faster than 15. On the other hand, those that lost 15lbs Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 222 in the same 3 months can see and feel the changes. They tend to be much more excited about the changes, and possibly for that reason they tend to have the motivation to carefully maintain. In summation, a weight loss rate of 0.5%-1.3% covers a good deal of fertile ground. If results and sustainability are your goals, losing somewhere between these extremes is likely to enhance your chances of success. Expectations for Body Composition Change Making weight loss or weight gain goals is pretty straightforward. We have a great deal of control about how much weight we gain on a muscle gain phase and how much we lose on a fat loss phase. But how much muscle can we expect to gain on a muscle gain phase (vs. fat tissue) and how much muscle do we have to put up with losing on a fat loss phase as just a cost of the process? Of course when we start diets we want to do our best, but how do we know if our results are in line with general expectations or so far behind them that we might need to reanalyze our approach and change something about it in a big way? Luckily, average expectations for muscle gains and losses on diets are not completely shrouded in mystery. From a combination of research and coaching experience (particularly looking at DEXA scans of body composition between phases), we can give you some general ideas of what might happen on your muscle gain and fat loss phases. You can use this data to enhance your own programs if you find that you can be doing better or to give yourself peace of mind when you realize you’re doing quite well! Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 223 CUT T IN G & MUSC L E LO S S The biggest determinant of muscle lost during fat loss phases (other than diet/ training and genetics) is the degree of body fat held by the individual during the start and end of dieting: • When you’re cutting down from any fat percentage to one that is above 20%, the chances of losing appreciable amounts of muscle is tiny so long as you’re following the principles well, or at least the calories and macros, while training hard • When you’re cutting from any fat percentage to 15% fat, you face a significant chance of muscle loss, but usually not more than 10% of total tissue losses. Thus if you lose 10lbs in this range, you might lose a pound of muscle. Nothing at all to worry about. • If you’re cutting from 15% or so down to 10%, you are risking some significant muscle loss, unless you’re using anabolic steroids. The average dieter might lose around 25% muscle for every 75% fat. If you’re dieting for Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 224 a physique competition, it might very well be worth it. Otherwise (and for female health reasons), it doesn’t often pay off because of the substantial muscle loss risk • If you’re cutting from 10% or so to the single digits without drugs, you’re likely losing upwards of 50/50 muscle to fat. In our estimate, this is not worth the cut, except for special cases such as needing that extra bit of conditioning for a show if you have muscle to spare compared to your competitors. GAI N IN G & FAT AC C U M U L ATI O N Outside of genetics and diet/training, the biggest factor in muscle gain to fat gain ratios is the training age of the woman (meaning how long she has been training, not her actual age, though that is another factor): • Women new to training (within the first 1 year) can gain muscle while losing fat if they gain no weight, and can gain 50% muscle and 50% fat on a gaining phase. • Women who have trained between 1 and 5 years can no longer expect to gain muscle and lose fat at the same time during an isocaloric diet (though that might still happen to some in a small way). On a gain phase, these women can expect to gain around 25% of their phase weight as muscle. This means that a woman who gains 10lbs of tissue will likely gain around 2.5lbs of muscle and 7.5lbs of fat. Sounds like bad news, but there is a bright side. Fat is MUCH easier to lose than muscle is to gain. And for most women that are not trying to get super lean, muscle loss is not a big concern on a diet. So if a woman can do 2 macrocycles per year of gain-maintain-cut, she can come out with 5lbs of muscle. 5lbs of muscle per year is a very impressive amount. If you gain an average of 5lbs of muscle per year during your 1-5 years of training, you’re going to be up 20lbs in muscle from year 1. That is a COMPLETELY DIFFERENT physique. • Women who have consistently trained and dieted well for over 5 years can only expect around 10-20% of their gain phase weight to be muscle tissue. If it sounds tough, it is. But that’s the reality. If you see ads for women gaining pounds and pounds of lean tissue in mere months after they’ve been training and dieting for more than 5 years, either they’ve had a drastic alteration in diet, have not been training hard recently and mostly regaining lost muscle, or Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 225 drugs are involved to some extent. Is this depressing news? Not really. This can still mean upwards of 3lbs of muscle gained per year. After 3 years, that’s close to 10lbs of muscle and a HUGE change in both physique and performance. Plus with all the years of training, this woman is probably starting from a pretty muscular point and these changes are just further refinement. • Taken altogether, from year zero to year 10 of hard training and proper dieting, an average woman may be able to gain around 40 pounds of muscle. Think about that…. 40lbs of muscle. That’s going to change health, performance and appearance in an absolutely astonishing way. Combine that with 10 years of losing 40lbs of total fat (though most or all of that fat can be lost within 2 years if fat loss is your main goal), and we’re talking about a total physique transformation. The big caveats to this are of course training inputs and genetics. If you don’t always train for muscle building (you might do endurance races, CrossFit, or many other great sports and activities), those numbers on muscle gain will be lower for you. Genetics play a big role as well. Some women will struggle to gain 10lbs of muscle in their entire lives, while some women will gain 60lbs of muscle over their bodybuilding careers. Both are extremely rare, but if you’re one of these women, your results will differ accordingly. The biggest reason we included these numbers in the book is to allow you to have realistic standards to which to hold yourself, and also, so that you don’t beat yourself up chasing the near-impossible. If you’ve been working with a trainer in your first year and haven’t gained any visible muscle, you might want to get a second opinion about his/her training methods. On the other hand, if you’re a 7-year veteran of hard training and dieting and you’re upset that you’re not gaining 10lbs of muscle a year, maybe a more realistic view can take off the needless pressure and allow you to enjoy your results more. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 226 Body Composition Standards Alright, we’ve got a good idea about how much muscle and fat we can gain and lose, but where does that leave us compared to other women. What’s a “good” body fat percentage to shoot for? What’s a very impressive body fat percentage? First of all, there is no such thing as a “good” body fat percentage. “Good” is how you treat others, not some amount of tissue on your body. As long as you’re healthy, there is a very wide range of body fat values that are just fine. How much is too much fat to be healthy? Anything much over 35% is likely to be indicative of or independently cause health problems. Now, this is not always Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 227 true, as there are numerous active people who have higher bodyfats than 35% but are very healthy. The 35% number is just a general reference to keep in mind, the number above which most women will be likely to face some health problems related to their fat stores. On the other end of the spectrum, anything under 15% fat is going to interfere with the reproductive system of the adult female. If you’re under - for a very long time, you’re going to be risking a higher chance of osteoporosis later in life, among several other problems. Does this mean that anything under 15% is bad? No way. But it means that the goal of LIVING in balance under 15% is actually unhealthy, so is not advised. Can you dip below 15% for special purposes every now and again and be just fine? Totally. Alright, so anything between 15% and 35% is healthy in the long term for ALL women. But if you’re looking for realistic goals and standards in fitness and not just for regular folks, what do those values look like? For the general population, anything below 20% fat is probably a good cutoff to consider “lean.” A female with 20% body fat will usually have no visible outcroppings of fat tissue on anything other than her secondary sexual characteristic bodyparts (breasts, thighs, glutes). Many (but not all) women will have the beginnings of abdominal definition just below 20%. We don’t want to paint this value as THE GOAL for EVERYONE. Absolutely not. The range for healthy and fit body fat levels can run much higher, all the way up to 35% or so as mentioned. But if you really want “a number” that most women can realistically work toward and achieve, a number that in some very small way indicates “I am fit,” then 20% body fat is that number. Just be careful to only use it as a guidepost and not as an all-costs goal. What if you want to be SUPER fit? To stand out in the fitness community as one of the super lean? First of all, it bears repeating that this should not be your FIRST goal as you enter the dieting world. As a matter of fact, if you have ANY Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 228 goal when you first start, and if that goal is body fat related, you can start just by reducing your own body fat percentage by 5 points in the span of 2-3 months. Once you’ve done that and put in a maintenance phase, you can, if you choose, take as many phases as needed to get to 20% fat. Only if you’ve comfortably been around 20% for some time (months) do we recommend trying to dive deeper. Where does this deeper dive take you? Anything under 15% is considered VERY lean in the fitness community. This body fat level is occupied by very few, most of them high level athletes or fitness competitors. Anything under around 15%, as mentioned earlier, is going to negatively impact long-term health somewhat, and thus, in our advice, should only be attempted with a distinct competitive or aesthetic goal, and not as a sustainable body composition level. Why are we mentioning such numbers at all? Because there is such a paucity of informed perspective on the matter. If you look out to all forms of media on this issue, you’ll typically find just two major perspectives. T H E ‘ B O DY FAT D O ESN’ T M AT TE R AT A LL’ S E C T • Radical thinkers in some sects of gender studies will like to paint a picture that even the question of goals and averages is itself flawed because women shouldn’t care about their body fat. The assumption here is that any degree of caring about body fat is a bowing down to the patriarchal standard that forces you to conform to the dominant and male-driven society’s standards of beauty. The first problem with this view is that it forgets aspects of physical health that may be related to the amount of fat you carry. Secondly, this view misses the possibility that you could have your own ideas about what you want to look like and that those ideas might not only embrace attractiveness but performance capacities as well. Many an athletic woman values her physique not as merely a means to be attractive, but as a badge of honor or evidence of her hard work and dedication. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 229 T H E ‘ B O DY FAT IS A L L THAT M AT TE R S ’ S E C T • Not all fitness competitors are experts in health and sustainability. This may or may not come as a surprise, but a small yet vocal minority of fitness women have intrusive body image issues of their own. These same women are often the most prolific posters and presence in social media, and they can paint equally distorted views on body fats. Some of these outgoing fitness women will have anyone who’s willing to listen believe that the best body fat is the lowest body fat, and that ANYONE can attain it and sustain it indefinitely. This is, of course, wrong on at least two counts. First, anything much below 15% is decidedly NOT healthy for long periods of time (more than a few months at a time). Secondly, genetics and lifestyle circumstances matter a LOT. It’s not in everyone’s cards to be under 15% body fat for a long time or even at all. And there is nothing wrong with being much, much higher than that. As you can tell, these two historically dominant perspectives have left a lot of women wanting. So please take our discussion of body fat standards with a big grain of salt. Feel free to use it to craft realistic goals but as always, make sure they are goals YOU want to accomplish, and not something you feel you have to or should do because of outside perspectives. Rules vs. Exceptions You might have a friend or two that got into shape incredibly quickly. They just trained a little more and ate a bit less or a bit healthier, and WHAM; within several months they were completely transformed. Better yet, they kept the fat off and kept adding muscle for months afterward with seemingly little effort. What gives?! On the other hand, you’ve maybe got a friend or two that has seemingly tried everything and nothing seems to work. Endless diets, workouts, restrictions and sacrifices for not much of anything in the way of results. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 230 Both situations may paint a bit of a distorted picture of the landscape of dieting for body composition and performance. If you’ve seen a bit too many of the first example, you might come into the dieting process with quite unrealistic goals and become quickly disappointed at your lack of progress. This can end up leading you to stall or quit an otherwise sound diet that was working just fine, other than the fact that it was not producing miracles. On the other hand, seeing a bit too many of the second example may lead you to be somewhat nihilistic about the dieting process. “Diets don’t work” might sound pretty accurate if you see enough people get pretty close to nothing out of them. This might make you more likely to never even start a diet that may help change your body greatly, especially over the long term. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 231 Why the disparity in results? Genetics and a dedication to the process are huge variables in the effectiveness of a diet. Someone who has not-so-great genetics for fat loss or muscle gain AND has less than stellar dedication (to be kind about it) may experience very little in the way of results. On the other hand, some women with gifted genetics for body composition and performance may also have the dedication to go with it, and consistently get absolutely outlandish results. The big challenge for YOU is to not get carried away and overly impressed with either of these rare types of individuals. Exceptions are just that, and if you base your reasoning and expectations for yourself on them, you’re almost sure to fail in one way or another. Aim for the middle ranges we’ve outlined throughout this text and you’ll be likely to experience most of the predicted effects. Save the exceptions for the comic books. Transformation Photo Pitfalls Instagram is intimating! Everyone posting transformation pics can seem fitter than you. Not only are people fitter, they started out much less fit than you and made triple the progress at double the speed! Oftentimes, their timelines of transformation make those changes seem effortless. Pictures of donuts, hot dogs, pizza and ice cream appear to mark their journey’s progression from fat to hyper fit. Maybe you’re even scared to start looking at your diet because you don’t feel like you can measure up. Maybe you have been dieting for a while and are NOT measuring up. What gives? Is everyone just that much better at this?! Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 232 A COUPLE OF THINGS GIVE, AND THEY ARE IMPORTANT TO CONSIDER: • A lot of popular transformation pictures are from first-time dieters that used almost every strategy (calories, macros, timing, etc…) in the book and trained their butts off. Good news: they lost weight. Bad news: their weight is often not sustainable and they may have lost muscle and sacrificed performance • A lot of the same transformations are posted by people with great genetics. The reason you see them on your feed is that they get a lot of “likes.” The reason they get a lot of likes is because they are outliers in degree of change or final outcome, which usually has a lot to do with the genetics of the individual. There are probably numerous transformation photos on social media that you’ve never seen, simply because they’re just not that unusually impressive. People pay the most attention to the extremes and that is human nature and just fine, just don’t hold yourself to outlier standards. • People only post the most impressive transformation photos. They may have done 7 diets in the last 4 years and THIS ONE was their all-time most impressive transformation. And guess what? This one is likely to be the only one they’ll ever post and that you’ll ever see. Most transformation photos never even make it out to the internet because their subjects don’t find them impressive enough to post. • Drugs are involved in some of the most extreme transformations, especially ones in which advanced fitness competitors or strength athletes seem to be eating tons of junk and still getting lean. With the above caveats, Instagram culture may not seem quite so intimidating anymore. If you’re into healthy, sustainable approaches to diet, stay the course and don’t let social media get too much in your way. There is nothing wrong with impressive transformation pictures… why not put your best foot forward? But when looking at these from the other end, we’ve got to remember that this is the BEST foot forward, not the average step, and that we mustn’t get intimidated or let our expectations be warped by it. Chapter Seven F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 233 P. 2 3 4 08 Fads & Fallacies In the Female Diet World This chapter, though failing to fully categorize the massive amount of fads, fallacies, and myths in the landscape of female dieting, attempts to walk through some common ones and clear the air. Science is stronger, after all, so let’s throw out the pseudoscience. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 234 Chapter Eight No matter how long this chapter is, it will never be long enough to include all of the myths, fads, gimmicks and misunderstandings that pervade the diet world. For this final chapter, we’ve included a short list of fallacies that includes a combination of ones that tend to continually reoccur and ones that seem to be gaining popularity at the time of this writing. She wants it all Wouldn’t being a high-performing CrossFit athlete be great? Of course it would, so please do work towards that and make it so! Now that you’re in great shape for CrossFit, you’re looking pretty damn good. Maybe good enough to do a short diet for a figure show and have fun competing? Ok, ok, that will take some work but it can definitely be worthwhile. Now a powerlifting meet is coming up and you wanna do it. Totally cool. You specialize your training for powerlifting for a month and compete and have fun. Now what? Now you want to be the best CrossFitter, powerlifter, AND figure competitor you can be. Is that possible? In a word; no. But hold on, so many women on social media seem to be doing a whole bunch of sports and are amazing at all of them! Some of these women even seem to have junk food all the time as well. AND they post pictures of their Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 235 families all the time, so you know they have a balanced lifestyle. How do these women have it all? Why can’t I have it all too? The reason you can’t have it all begins with the very structure of time itself. For us humans with mortal bodies, time is finite. Can you pick several major things you want to prioritize and fit them in? Can you do your work well, train for bikini and CrossFit, and still have family time? Totally. But if you add weightlifting and being a soccer coach and training for a marathon to that, you’ll find that one of two things happens; either you run out of time to meaningfully fulfill one of those categories (you can’t coach soccer for 5 minutes a week and expect results), or you’ll overreach, which will eat into your recovery time. If you want to do things well, a finite day prevents you from doing too many of them well. In addition, things like training for both a marathon AND a powerlifting meet simultaneously can retard your progress toward BOTH. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 236 One important variable that comes into play, even if you can squeeze in all the training hours for everything, and your goals are not mutually exclusive, is recovery. Even if you do have time in the day to train for CrossFit and Powerlifting and Bikini, do you have that kind of potential to recover? Yes, you might be able to recover from all of those training sessions, but imagine if you cut one of them out and were left with just 2 sports. Could you recover better? Absolutely. Any time spent doing another sport is time that could have been used either to train more for the first sport or to recover more for the next training session for the first sport. ANY training outside of one sport interferes at least somewhat with any other sports for that same reason. This is why it’s nearly impossible to be the best you can be at more than one sport at a time. If you go way far off into the multisport and multi-hobby direction, you end up having so much cross-interference that the performance and enjoyment level of EACH of your sports and hobbies dips so low as to no longer make them worthwhile. So when you’re choosing your sports, hobbies and priorities for any slice of future time in your life, choose the several (at most) that matter most to you. The same fundamental reality of constraints applies to diet choices. Can you eat donuts and look great? Yes. Can you eat donuts and look your BEST POSSIBLE? No. Calories eaten through donuts could have been eaten through foods that provide healthier fats, more fiber, higher micronutrients and foods that are more Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 237 filling. This will make your dieting results better and the decreased hunger will keep you saner for longer in a hypocaloric state. Is there a logical tradeoff that everyone can make personally between how many tasty foods they get to eat and how they look and perform? Definitely. There is also a time factor whereby you can choose to have several months of balanced fun and enjoy donuts and other foods more often, and several other months of more restrictive dieting to sharpen up your physique and your performance, most of which you’ll keep even after returning to balance again. What we want to make clear is that you can have those donuts or those other sports BUT you must accept that there will some tradeoff or sacrifice. You can’t have it all at the same time. You can have a lot at the same time, or almost all of it spread over different times to be sure. Our best advice is to pick your top choices of activities and priorities and do well at those. You don’t have to stick to one thing but you don’t have to do 500 things either. In dieting, be comfortable with restrictions during a goal-oriented diet phase and enjoy delicious foods during your balance phase, but understand that mixing those two approaches at the same time yields less results and pleasure from both. Dieting without a precise goal “I just wanna keep losing weight until I like how I look.” Nothing wrong with that, but as we have discussed in depth, if you run a diet much longer than about 3 months, you risk ruining your look by losing muscle and ruining your diet by burning out. So, fine, we’ll watch the calendar and the scale, but we’re still not going to make a weight loss goal. With no goal, at the end of the 3 months, you might have only lost 2-3 pounds. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 238 All the dieting time and for what? Basically some water weight? Or, you could find that you’ve lost 20lbs. Great, 5lbs of muscle tissue down the drain, and now you don’t look nearly like you wanted. The purpose of a weight goal isn’t just to motivate you (you can have that without a scale) or to tell you when the diet is over (a calendar can do that just fine). A weight goal should primarily be used to pick a logical amount of tissue to lose. An amount that doesn’t undercut your potential or lead to overwhelming fatigue and muscle loss. Once that logical amount is decided, the weight goal can keep you on track to make sure your rate of loss is not too quick and not too slow. You don’t have to have a super long term mega goal to take over the planet with your new robot warrior body. But to make the dieting process much more Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 239 effective, at least short term scale weight goals are highly recommended. Wait… using the scale is scary and bad! Right? Scale Phobia To many women, scales are scary. Like the ravens of centuries past, today’s bathroom scales seem only to carry omens of future despair. If you weigh in, there’s a good chance you’ll be pissed about the resulting number and it will ruin at least your minute, if not your morning or your whole day. On the other hand, the scale can make you happy. If you see a lower number (or for those of us gaining intentionally, a higher number) than you were expecting, you can experience a great deal of joy. But this is the joy of meth addicts and compulsive gamblers. One day it’s great news and the songbirds are singing your tune, and the next day it’s terrible news again as ravens fill the sky with their incessant squawking. Is the scale truly this evil? Should we do away with scales altogether? Almost certainly not. Scales are simply tools, powerful tools that can be used with a productive, calm, and measured attitude - just as they can be abused. Some thoughts on scales: Only use the scale with a purpose. The scale cannot decide your goals for you, you need to decide them in advance. The scale is not a moral compass. You are not good or bad depending on what you weigh. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 240 The scale does not punish nor reward. Having ice cream or lowering your carbs has to do with your goal, not just the number on the scale. The scale is not a perfect measure of health. There are many healthy bodyweights, especially if you’re active. The scale is not a measure of how attractive you are to other people. People care about how you look and act, not how much you weigh. There are many great looks at many bodyweights. The scale is not a measure of how attractive you are to yourself. Are you really the kind of person that derives their worth from one number? The scale is not evil, don’t throw the scale away, burn it, punish it, anthropomorphize it, hate it. It can be a great tool when used with purpose and calm. There are times to use the scale and times to put it away. If you find yourself weighing in at random times of the day for no good reason, stop! Only weigh in when you need to record your weight for diet tracking purposes, which might just be 2 or 3 times per week. Remember that weight fluctuations can be several pounds in magnitude. The multi-week trend is what matters for your weight, not the fact that you were heavier today compared to two days ago. Do you have to weigh in on a balance phase? Maybe once a week or every 2 weeks, sure. If you’re addicted to weighing in every day for no data-driven diet reason, it might be a good idea to stop that behavior. Always view the scale as a tool that gives you a cold, logical number. The less emotional you choose to make Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 241 the ‘weighing-in’ process, the less negative power the scale will have and the more useful it will become to you. Understanding variability in weight fluctuation When you’re on a fat loss diet and your weight does not drop on a particular morning when you weigh in, what’s the likely cause? Here’s how we split up the probabilities: • 50% chance: water fluctuation from different food containing different amounts of salt, carbs, volumes, or differences in timing, and water intake from the day before • 30%: water fluctuation from differences in body processes and hormones, including digestion time differences, sex hormones like estrogen, progesterone and testosterone, diuretic hormones like ADH and aldosterone, and cortisol • 20%: actual tissue loss from burned or added fat and/or muscle Any time your weight doesn’t drop when it’s supposed to or rise when it’s supposed to (assuming you are following your diet plan precisely), it’s very, very often (80% of the time or so) going to be due to factors OTHER THAN your tissue loss or gain progress, which is the only variable we really care about. This is one of the big reasons why we recommend weighing in between 2 and 3 times per week. If you only weigh in once a week, just one day of unusual hydration or stress before the weigh in day can make the entire preceding week seem to have you thrown off of your goals. On the other hand, if you weigh in every day, most of what you’ll be detecting is the noise of water fluctuations. Thus, by weighing in every 2-3 days, we get the best signal-to-noise ratio and we can see our weight trends more clearly and make faster and more accurate food intake and activity adjustments to stay on course. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 242 That being said, even with 2-3 weigh-ins per week, tissue changes can still be obscured by other factors, especially during menstruation cycles that at certain periods can bloat you up by over 5lbs for a week at a time. This is why we make the strong recommendation that you write down and possibly graph your weights and look at the trend over days and weeks (and with reference to your menstruation cycle), rather than by individual daily weights. Here’s where the fallacy comes into play. If you attach yourself psychologically to the idea that you should lose, gain or maintain weight in a linear and steady fashion, you’re betting right around 20-80 odds on NOT being satisfied with any particular weigh-in number. Ok, the exaggeration here is that tissue weight IS changing over time in most cases, so it’s not quite 20-80 odds, but even with relatively rapid weight loss, around half of the daily weigh-ins will either be upward (gain) or about the same as the number yesterday. Are there any other situations in your life where you put strong emotional attachment into a 50/50 situation? Is your significant other cheating on you 50% of the time when you expect 100% faithfulness? Does your boss punish you for good work done half the time even though you almost always do good work? Do your kids only show up home from school half the time even if you expect them to show up every day? Of course not, that’s just plain insanity. And guess what, mathematically, it’s the identical insanity you’re setting up for yourself when you get hung up on a single scale number not going the way you like during a single day. What’s the better approach? Be as emotionless as you can be with the number that pops up, do a great job on your diet, and then feel free to be emotional with the resulting trend line of average weights when you plot it into a graph with weeks of data. The resulting emotion will be the soothing chill of cold, hard science easing the weight off of your body over time if you’re losing fat, putting weight on slowly if you’re gaining muscle, or keeping it vibrating at a single weight, if you’re maintaining or living in balance. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 243 We i g ht Va r i a b i l i t y: M u s cl e G a i n We i g ht Va r i a b i l i t y: M a i n t e n a nce Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 244 We i g ht Va r i a b i l i t y: Fa t l o s s Figure 8: Typical Weight Variability Patterns on Muscle Gain, Maintenance, and Fat Loss Phases. It’s ok to be hungry – it’s temporary. The most powerful and central strategy of a fat loss diet is the hypocaloric condition: fewer calories in than out. While hypocaloric dieting is indispensably powerful, it’s also homeostatically disruptive. It’s literally, in no uncertain terms, throwing your body off balance. When you breathe out on a hypocaloric diet, the very carbon, hydrogen and oxygen that used to compose your fat cells is blown out. When a spaceship is losing fuel or parts of it are falling off after a laser gun battle, is it normal for some indicator lights and sounds to be flashing and beeping in the Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 245 cockpit to alert the crew? Of course it is! Because our bodies largely evolved in an ancestral environment of common periods of starvation, our brains have become very good at telling us when we’re losing our precious fat cargo. The signals come in hunger, restlessness, cravings, and low energy. You live in the modern era however, and you can have food any time. You are not in real danger of starvation (though your body’s response is the same as if you were). You’re going hypocaloric for a purpose, and there is no fear of you becoming malnutritioned or risking your life or health. Your conscious mind knows this because it learned so within its lifetime. Your body, on the other hand, has programs that developed before the modern age to keep humans alive. So it’s just going to keep bugging you, telling you that you are hungry and tired in an effort to get you to hold still and eat more and stop losing weight. What is the best strategy for dealing with the unpleasant nature of dieting? Firstly, have your diet bases covered with a sound approach, and sleep to manage fatigue well. If this is all on point, you’ll have to do what the first sentence in this paragraph mentions; deal. Caffeine, meal time, lots of fruits and veggies and maybe even carbonated beverages can help with some elements of hunger and fatigue, but a fat loss diet just won’t ever feel like maintenance. There will always be some degree of suffering involved. If you understand that this is just a part of the process and do your best, success will be just around the corner and so will the end of feeling hungry and tired. If you get shocked into thinking something is wrong every time you feel low in energy or a hunger pang hits, you’re going to do exactly what your brain is programmed to get you to do: fall off the diet and overeat food. If you want to look or perform only like your genetics intended, it’s totally fine to give in. But if you’re trying to look or perform like something else, something you want more, then stay the course and except the discomfort. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 246 Th e ha z a rd s o f wa n t i ng t o pus h t o o far for too long We’ve all been there or will be at some point, and it’s a great place to be. You’re at the tail end of a diet in which you’re meeting your weight goals on time, every time, and you’re sometimes even a bit ahead. You’ve worked your butt off, but the results are so good, you’re motivated as can be. Then you turn your calendar to the day the diet is over. Turns out it’s been 12 weeks and it’s time to switch gears into maintenance. Ugh! Why maintenance now when you’re on such a hot streak! Why not keep going while the going is good and lose even more fat or gain even more muscle? To be sure, sometimes it’s ok to do that, but for only perhaps several weeks at a time. And the choice to keep going has to be made when you feel VERY good to keep going and you’ve either added very little food in for muscle gain or so far cut very little food out for fat loss. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 247 In general, the advice has to be to stick to the plan and make the needed change into maintenance mode (or if long term muscle is the goal, muscle gain mode after a fat loss phase). This advice was not chosen at random, but because it represents the safe limits of both psychological and physiological sustainability. If you choose to go further than needed on a fat loss phase, you risk burning out psychologically at the end, which might make you more prone to binge and gain back weight instead of maintaining your end weight. It can even negatively tint your perceptions of dieting for the future and make you needlessly diet-averse. Physiologically, pushing a fat loss phase to far may result in lost muscle that can take quite a while to get back… time you could have spent gaining new muscle. Going too far on a muscle gain phase can psychologically backfire by making you fatter than you wanted to be. This can leave you with a sour taste for muscle gain phases for a long time to come, leading you to avoid them too often and pay the cost in lost opportunities to gain muscle. Physiologically, going too far on a muscle gain phase can lead to a situation where you’re scrapping for a measly pound of muscle by gaining 5 or more pounds of fat… fat you’ll have to work hard to diet off later. If you’re excited about going further on a fat loss or a muscle gain phase as the phase comes to an end, that’s great! Switch gears on time like you’re supposed to do and walk away with a psychologically and physiologically awesome experience. Save that excitement for the next time you diet… you’ll need it. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 248 FAD D IET S AN D SC IENC E The super fast new fad diet worked for my friend! Should I try it? If it worked, it probably worked because it followed at least some of the dieting principles described earlier in this book. Most fad diets feature lower calories or a form of creating lower calories (low carb foods are hard to eat in amounts that will make you fat, for example, so many diets greatly restrict carbs). Many fad diets are high in protein to keep you fuller longer, or have you supplement with various stimulants to help control hunger while promoting energy levels. You can certainly try your friend’s fad diet and get the effect of some of the underlying principles of diet that make all diets that are effective work. On the other hand, if you design your own diet based on the principles described in this book, you can get ALL of the principles to work for you and produce even better results. And more often than not, you don’t even have to do anything crazy and needlessly restrictive like most fad diets have you do. A bonus to doing it this way is that the same patterns you establish during your diet (plenty of protein at each meal, fruits, veggies, and grains often and tracking your intake) translate incredibly well into healthy maintenance and balance. What do you do if the PsychoDietXL you ran comes to an end? You’ll have to establish healthy, performance-promoting and sustainable eating practices from scratch anyway. ALC O H O L AN D D IET ING Alcohol has several predictable effects on your body composition and performance. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 249 When consumed, alcohol: • Increases fatigue and interferes with fatigue dissipation after hard training • Creates a hormonal environment which makes fat storage more likely for the next several hours (while the alcohol is in your system) • Creates a hormonal environment which makes muscle loss more likely for the next several hours (while the alcohol is in your system) • Adds 7 calories per gram consumed, NOT counting the added calories from sugars present in mixers, wine, and beer • Disinhibits you and makes you more likely to go off-plan on your diet • Makes your cravings for junk food shoot up That sounds pretty nasty! The bad news is that it’s true. The good news is that it’s proportional to the amount of alcohol consumed. Thus, a.) If you have a couple of drinks a week, pretty much close to nothing will be negatively affected except for the obvious calorie increase b.) I f you have from one to a couple of drinks every night or so, the negatives on body composition and performance will be slight but meaningful c.) I f you have 4-6 drinks a night on many nights, you’re taking a huge chunk of effect out of your body composition and performance improvements d.) If you get drunk several times per week, you’re severely inhibiting your progress Thus, like many of the insights in this book, the result is a tradeoff and a choice to you, the dieter. If you want the best possible results, save your drinking for a maintenance or balance phase. If you need a glass of red wine or a beer now and again to relax, don’t sweat it. But if you’re a steady drinker, understand that you’re leaving some results on the table and choose accordingly. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 250 T H E FAL L ACY O F “ EATI NG M O R E TO LO S E W E I G HT ” What an odd question, on the face of it. Isn’t food intake supposed to be at some minimally low level and not at a high level for weight loss to occur? Yes, and under normal circumstances (90+) percent of the time, you have to eat LESS to lose more weight, not more. So just to explain why this question is considered fallacious and included in this chapter, we have to say that for most people, the answer is a resounding “yes.” As a matter of fact, a follow-up answer should be “and you might even be eating TOO MUCH to lose weight,” which is much, much more common than not eating enough. Under some very special and rare circumstances, however, eating more food might lead to losing more weight in the long term. Here’s how it happens, step by step: 1) Woman diets for longer than 3 months, diets much faster than 1% bodyweight lost per week, or both. 2) Woman’s metabolism begins to slow down, forcing her to eat even less than otherwise to keep losing weight, making her diet even more extreme 3) Woman’s unconscious behavior begins to bias her in the direction of less movement and more idle tasks or total rest. Her training at the gym becomes less voluminous and heavy, burning fewer calories. Instead of walking her dogs like she usually does, maybe she’ll have her significant other do it. Instead of walking up the 4 flights of stairs at work to deliver her report to the board of directors, she might take the elevator. When speaking to the Board, she might use fewer hand gestures and body motions to help accentuate her delivery, and so on 4) Her weight begins to stall out because her slower metabolism and lower energy demand close the calorie deficit originally created by lowering food intake. Food intake must be lowered again 5) In frustration at her slowing weight loss and in accordance with her hunger pangs, she begins to cheat on her diet a couple of times per week. All of these factors combined and she’s now fully stalled in weight loss Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 251 Now, she reads online that eating more food can help her lose more weight, so she tries it out. 6) She starts eating more good food every day 7) Her metabolism starts to climb back up because of the higher calorie intake 8) Her hunger levels begin to subside and her cheat meals stop or lower in size and frequency 9) She’s got energy again, and she begins training hard and moving around a ton! The extra food she’s eating is only about as many calories as the cheat meals were (per week), but because she’s moving more than she was when she was alternating starving and cheating, she begins to lose weight again Is there some magic violation of the laws of thermodynamics by which she’s now losing weight faster on more calories? No! She’s just expending more calories and no longer cheating as much and taking in extras. Is there some other, better way to go about the process of using this advantage than she did in the example? Of course there is… that’s what the maintenance phase after a fat loss diet is for! One of the big purposes of this phase is to slowly reduce hunger cravings, raise unconscious activity levels, and raise food intakes to stabilize weight. Thus, the only real time that ‘eating more to lose more weight’ works in any sense is if you’re not properly putting maintenance phases into your plan. If you diet in a proper sequence and take maintenance phases every 2-3 months of hypocaloric dieting, you’ll only need to be concerned with one type of diet modification when you’re in the fat loss phase: cutting calories, not adding them. DETOX ES , C L EAN SES , B O DY W R A P S , M AG I C P I LLS , D R I N KS , AN D T HE NATURA L IST IC FA L L ACY There is usually something to every single type of fad product that hits the market that makes it SEEM to work to some extent. • Detoxes and cleanses restrict you to very few foods or only certain fluids, Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 252 so your body water drops and your calories drop as well, leading to several pounds of water loss and possibly a couple pounds of tissue loss • Body Wraps may change the distribution of water in your body away from the wrapped area, which for several hours or even days can make them look slimmer • Diet pills and drinks often have copious amounts of caffeine, which helps combat hunger and gives you daily energy to function on lower calories But as you may begin to notice, water weight drops and the effects of just one supplement (caffeine) are a long shot from producing real, lasting results. This is more than just conjecture. Every time the light of formal scientific laboratory research is shined on these kinds of gimmicks, their effects simply don’t measure up or aren’t detectable at all. Our best advice; save your money and invest in proper diet and training instead. Use that money to buy yourself something you’ll actually like, unless you plan on wearing body wraps to your next social outing. I Want to Gain Muscle, but I Don’t Want to Gain Any Weight Beginner and even some intermediate women can just train, eat, stay the same weight, and gain muscle. For the more experienced women, however, temporary gains in bodyweight are the best ways to gain muscle. By going through a muscle gain phase of slow and steady weight gain, the power of a hypercaloric diet is put to work on building muscle, and it’s the most powerful of the muscle-building diet principles, so it pays off big. For the advanced trainers, going into hypercaloric eating mode is the only way to keep gaining appreciable amounts of muscle. YES, you’ll gain some fat in the Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 253 short term. The good news is that you can always burn the fat off later and keep the muscle. If you’re never willing to gain even a little bit of slow and steady temporary weight, you will not be gaining much muscle, especially as you are involved in fitness for longer and longer. If you NEVER want to gain any weight but still want to be muscular, you’ll be making the process both needlessly hard and needlessly fruitless. You don’t have to gain much… just 5 pounds spread over 8 weeks is a very good start. Doing that 2 times a year can have an impressive long term impact on your muscle size and thus your physical appearance and performance. Finally as discussed in the original Renaissance Periodization diet book in detail, natural does not always mean better. It sounds nice and it feels good, and in some cases it is great. Just keep in mind that there are plenty of natural things (hemlock, tetrodotoxin) that will literally kill you and unnatural things (Gatorade powder Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 254 intra workout, vitamin supplements) that are great for you. Determining whether something is natural does not give you any idea whatsoever if it is good for you. Closing Thoughts If you have read this book in its entirety, you now have the scientifically based knowledge and tools to build your own diet for healthy and sustainable body composition changes and maximum athletic performance. Your first task in putting this information to good use is to decide what your long-term goals are for the next 3 months to a year. Remember that changes in physique require periods of imbalance. The upside is that subsequent periods of balance are more enjoyable when your goals are reached and you have the body you want. The choice to make the change is yours. If you do it, do it with all of your effort, and then enjoy the results. As you endeavor to write your first diet, do not get overwhelmed by the abundance of details in this book. As suggested earlier, start slow. Drop back in to Chapter 1, and start playing with the top two dieting principles. Take your time and work your way up to a detailed diet implementation; you don’t want to get burned out or frustrated. There is a lot of information to assimilate and it will take time to make it second nature. The women pictured in this book are RP clients of different sizes and ages and at different places in their fitness journeys. They are pictured in various aspects of their lives. We wanted to portray the fullness of a woman’s life for two reasons. First, fitness and health have a huge impact on all aspects of life at every age and stage of athletic development. Secondly, the fitness and body composition changes you make are only a very small portion of all the aspects of your wonderful life. We strongly encourage you to make decisions in this arena with Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 255 full consideration of the temporary sacrifices you will have to make to other parts of your life in order to achieve these types of changes. The choice to change must be one that you want to make, and are willing to fully commit to. If the sacrifices outweigh the benefit to you, then simply use the nutrition guides in this book for healthy maintenance and balance and don’t look back. Finally we would like to say that in writing this book we hope to contribute a bit to the glue binding a newly mounting congregation of women. Intelligent, informed women making the choice to be strong and in control of their own destinies- women finding purpose and self-actualization through sports and performance. We are not just talking about top-level athletes or even moderate level competitors. We are also talking about the woman with the busy life, family, Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 256 and other obligations, who shows up at the gym dead tired because being better than she was yesterday matters to her. Gone is the era in which we were told that we were too fragile for sports. Now is the time when the mother of high school students might be in the garage with an Olympic bar busting out deadlifts after dropping her kids off at school, shooting for that PR with bloody shins and cold hard determination. Gone is the era in which a woman’s self worth was more likely to be determined by how she looked, now is the time for us to value ourselves and other women for what we can do and achieve. It is a powerful paradigm shift and we can only hope that we contribute in some way by providing accurate scientifically based information to women seeking to constantly grow and progress. Chapter Eight F a t L o s s , M u s c l e G r o w t h & P e r f o r m a n c e T h r o u g h S c i e n t i fi c E a t i n g P 257 Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific Eating Renaissance Woman D r. J e n n i f e r C a s e , D r. M e l i s s a D a v i s & D r. M i k e I s r a e t e l