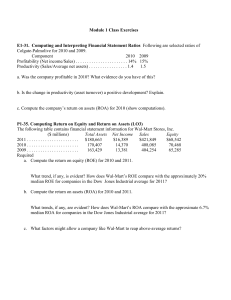

Spring 2022 NBA 5060 Lectures 4 through 6 – Profitability Analysis 1. Why is profitability analysis important? 2. Profitability Analysis Relative vs. Absolute Analysis Cross-sectional vs. time-series 3. Profitability Ratios Return on Equity (ROE) Return on Assets (ROA) Decomposing these measures 4. Some Key Takeaways from Profitability Analysis Additional Notes: Supplemental note on the economic relation between accounting ratios and the cost of capital Lectures 4 through 6 Page 1 of 15 1. Why is ratio analysis important? The value of a company depends on its ability to grow and generate profits: Growth and Profitability Product Market Strategies Operating Management Financial Market Strategies Investment Management Financing Decisions Payout Decisions Goal: Evaluate effectiveness of the firm’s policies in each of these areas. The ability to grow and generate profits is a function of the firm’s operating, investing, and financing decisions. Ratio analysis provides a means of evaluating the effectiveness of the firm’s operating, investing, and financing policies: Sustainable Growth Rate Dividend Payout Ratio ROE ROA PM Operating Management Lectures 4 through 6 CEL CSL ATO Investment Management Financing Decisions Payout Decisions Page 2 of 15 2. Profitability Analysis What is it? A means of placing structure on the financial statements to help organize, evaluate, and digest the information provided about the firm’s operating, investing, and financing activities. Allows meaningful comparisons across companies and over time (relative analysis), as well as benchmarking against rules of thumb (absolute analysis). Relative Analysis – compares the financial metrics of a firm relative to the financial metrics of some comparison (i.e. control) group. Absolute level of the numbers does not matter as much as whether they are higher or lower than the comparison group. Two basic types of relative analysis: Cross-sectional approach – compare the firm to industry peers on a number of dimensions. Time series approach – use the historic performance of a firm as the benchmark. Cross-sectional comparisons are useful in benchmarking how the firm is doing relative to industry peers, while a time series approach can reveal trends within the firm. Absolute analysis – compares the financial metrics of a firm to absolute levels. Matters less where they rank relative to other firms. e.g. Is operating cash flow positive? Does ROE exceed the cost of capital? Lectures 4 through 6 Page 3 of 15 3. Basic Profitability Ratios Return on Equity Financing Activities (Debt Policy) Return on Assets Profit Margin Operating Activities Lectures 4 through 6 Asset Turnover Investing Activities Page 4 of 15 Return on Assets (ROA) ROA NI Interest Expense (1 t ) EBI Average Total Assets Average Total Assets Other common variations: This is common, but is technically a mismatch of the numerator and denominator. ROA NetIncome AverageTot alAssets ROA EBI Beginning or Ending Total Assets Use of ‘Ending TA’ requires less data to form a time series Disaggregating ROA: ROA Profit Margin x AssetTurnover NI IntExp (1 t ) Sales x Sales AverageTot alAssets What is a reasonable absolute benchmark for ROA? What factors drive cross-sectional differences in ROAs? Lectures 4 through 6 Page 5 of 15 Average Median ROAs, Profit Margins, and Asset Turnovers Across Industries from 1982-2018 Lectures 4 through 6 Page 6 of 15 Decomposing ROA into Profit Margin and Asset Turnovers: Can be used to check for sustainability of improvement (or decline) in ROA ROA Profit Margin x AssetTurnover NI IntExp (1 t ) Sales x Sales AverageTot alAssets Profit Margin: Profit margin is the amount the firm generates from every dollar of sales. Economics of margin: Industry factors o Whether the industry is growing, mature or decline, patent protection, monopoly rents etc. Sales volume o Fixed costs get allocated to a larger sales base. Sales price o Important to examine if market share is being generated through lower pricing. Expenses o While improving margins through expense reduction is good, it has limits. Decomposing Profit Margin – simply divide each net income line item by sales: Sales: COGS: Selling & Admin: Depreciation & Amortization: Other Revenue: Income Taxes (add back tax on interest expense): EBI: Decomposition allows the analyst to trace changes in profit margin to specific line items for additional analysis. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 7 of 15 General Issues in Computing Net Income One of the primary objectives of analyzing the income statement is to get a sense of the relative permanence of a firm’s earnings. Items Affecting Earnings Permanence and the Prediction of Future Earnings Income from continuing operations: Should include only the normal, recurring, relatively sustainable, ongoing economic activities of the organization. The one exception is often termed ‘Special Items’ Special items or unusual items include any relatively infrequent or non-recurring items that nevertheless tend to arise from a firm’s on-going, continuing operations. Some frequent special items to consider when assessing the permanence of earnings: Gains and losses on sale of securities. Restructuring charges. Gain or loss on sale of PPE. Beyond this, review the MD&A, where you’ll for the business reasons explaining changes in income statement line items. This information is useful not only for understanding changes in recent performance but also for developing expectations for future earnings. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 8 of 15 Asset Turnover: ATO Sales AverageTot alAssets Asset turnover is a measure of asset efficiency Can be changed by o Increasing sales revenue using the same assets o Outsourcing o Disposing less productive assets o Decreases when additional investments generate lower marginal revenue Asset turnover has a balance sheet orientation and can be disaggregated into: Inventory turnover ratio (COGS/Inventory), Current asset turnover ratio (Sales/Current assets), PPE turnover ratio (Sales/PPE) etc. Turnover Components (note this is not really a decomposition as the components do not sum to asset turnover): Sales AR Turnover Average or Ending AR Inv. Turnover Sales or COGS Average or Ending Inventory Fixed Asset Turnover Technically, should be ‘sales on account’, but this is hard to measure. Sales is more appropriate as a Total Asset decomposition, while COGS give s a better measure of actual times inventory turns over. Sales Avg. or Ending Net Property, Plant, and Equipment PM, ATO, and their decompositions are useful for (1) explaining trends in ROA (and ROE), (2) forecasting future financial statements and conducting sensitivity analysis, (3) explaining changes in value through their impact on ROE. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 9 of 15 Return on Net Operating Assets (aka Return on Invested Capital, ROIC) RONA EBI EBI Avg.(Equity Debt) Avg.(Total Assets Operating Liabs) You can decompose RONA similarly to ROA by simply multiplying and dividing by sales. What is the appropriate absolute benchmark for RONA? In general, which is a more appropriate profitability ratio, ROA or RONA? Lectures 4 through 6 Page 10 of 15 Return on Equity (ROE) ROE Net Income Average Shareholde rs Equity Other variations you might run across: ROCE ROE NI Div on Preferred Shares Avg .CommonShar eholdersEq uity Net Income Beginning or Ending Sharehold ers Equity Disaggregating ROE: #1 ROE NI Int Exp (1 t ) AverageTA NI x x Average TA NI Int Exp (1 t ) AverageSha reholdersE quity #2 ROE RONA AvgDebt InterestExpense(1 t ) RONA AvgEquity AvgDebt What is a reasonable absolute benchmark for ROE? What factors will drive cross-sectional variation in ROEs? Lectures 4 through 6 Page 11 of 15 Profitability ratios with preferred stock or minority interest Preferred stock and minority interest require adjustment to the ROE decompositions: ROE decomposition #1 ROE NI Int Exp(1 t) MII NI Pref Div AverageTA x x Average TA NI Int Exp(1 t) MII Avg Common Equity ROE decomposition #2 ROE RONA' AvgDebt InterestExpense(1 t) AvgMI MII RONA' RONA' AvgEquity AvgDebt AvgMI AvgEquity AvgPrefEquity PrefDiv RONA' AvgEquity AvgPrefEquity Where RONA’ = RONA ' NI Int Exp(1 t) MII Average(De bt Common Equity Preferred Equity Minority Interest) When will these adjustments matter most? Lectures 4 through 6 Page 12 of 15 4. Some Key Takeaways from Profitability Analysis: I know how to compute all the ratios, but I’m still not sure I know when to actually use them. There are two primary objectives to profitability analysis at this point. First, use ROA and ROE as a baseline evaluation of the firm relative to past performance (e.g. ROA seems to be deteriorating) or relative to other firms (e.g. Dell consistently has a higher ROE than other computer manufacturers). This will give you a quick glimpse of whether the firm is well positioned going forward. Second, use the ROA decomposition to determine the cause of increases (decreases) in profitability. This can help determine if the change in ROA is likely to be permanent or transitory. Finally, both ROA and ROE often tell similar stories. As we’ll see, ROA drives the value of the firm, while ROE drives the value of the equity. Hence, ROA tells you something about overall profitability and firm value while ROE tells you how effectively the firm is using its capital structure. Thus, they are important ratios for valuation purposes, as we’ll see later. Firm X increased their asset turnover from 1.8 to 2.0. Is this good? Is this significant? How do I know? More generally, this question reflects the lack of intuitive definitions for several of the ratios we examine. So the best way to evaluate this is to consider what the ratio actually means and do some sensitivity analysis (i.e. ‘as if’ calculations). In this case, the increase from 1.8 to 2.0 means that for every dollar of assets employed by the firm, the firm increased sales by $0.20. Thus, if the firm has $100 million in assets, efficiency improvements alone are responsible for a $20 million increase in revenue. You can then trace the improvement to earnings (via the profit margin), and EPS, which is particularly meaningful. If you tell investors that efficiency improvements alone contributed an additional $0.10 to this year’s EPS, they will be able to judge the economic significance of the improvement more readily than if you simply report a 0.2 increase in the asset turnover ratio. I know weighted cost of capital (cost of equity capital) is a decent benchmark for RONA (ROE). Is there anything else I should look for? Look for the relation between strategy and the components of RONA. If a firm is trying to be a cost leader, it should have relatively high turnover and low margins. The opposite is true for a product differentiator. If the ratios don’t seem to match up with the firm’s strategy, this requires further investigation. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 13 of 15 A Supplemental Note On The Economic Relationship Between Accounting Ratios and the Cost-of-Capital Three accounting based return-on-investment (ROI) measures are among the most commonly used financial ratios in fundamental analysis: return-on-total-assets (ROA), return-on-net-assets (RONA), and return-on-equity (ROE). Students who encounter these financial ratios for the first time often find them a little confusing. The purpose of this note is to explain the rationale behind these ratios and discuss the economic relationship between each ratio and the cost-of-capital. 1. Constructing an accounting ROI All three ratios use accounting numbers to measure the rate of return on investment (ROI). Each is a measure of earnings divided by a measure of the capital (or investment) base. The difference between the three lies in the definition of the capital base, earnings to that capital base, and the cost of that capital base. The single most important concept to keep in mind in working with accounting ROIs is that the earnings and the cost of capital must be consistent with the capital base as defined in the denominator of the ratio. Consider the following table: Ratio Representative Formula ROA RONA ROE Capital Defn Total Assets Earnings Defn EBI Cost of Capital Cost of financing TA ‘Normal’ levels Approx. 6% EBI Avg .TA S .T .Liab Net Assets EBI Cost of financing Net Assets Approx. 9% Net Income Average Shareholde rs Equity Common Equity NI Cost of financing Equity Approx. 12% NI Interest Expense (1 t ) Average Total Assets Notice that each ratio has a different definition of capital. Once you have selected a given definition of capital, you are constrained to choose a definition of earnings and a definition of the cost of capital which are consistent with that capital base. Mismatches result in ROIs that either understate or overstate economic performance. 2. ROA For example, the capital base for ROA is total assets. What is the earnings generated by this capital base? It’s EBI (called “NOPAT” in your PH textbook for “Net Operating Profit After Taxes”) This is the after-tax earnings with interest expense added back. We add the interest expense back because this expense is used to service debt, which is part of the capital base. We want to measure the return generating power of total assets. If we do not add back interest expense, we would understate the firm’s return generating power pertaining to its total assets. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 14 of 15 What is the cost of this capital base? It’s the cost associated with financing the total assets of the company. The balance sheet equation tells us that total assets = s/t liab + l/t liab + shareholders’ equity so the appropriate cost of this capital should be the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for these three sources of financing. For example, the typical firm has a capital structure of 1/3 s/t liabs (such as current payables and accruals), 1/3 l/t liabs (such as bonds etc.) and 1/3 equity. The WACC for this firm would be computed approximately as follows: Source of Financing Short term liabilities Pretax Cost of Financing Nil Effect of Tax Shield none After-tax Cost of Financing Nil % Weight 1/3 Contribution to WACC 0.0% Long term liabilities 10.0% t=40% 6.0% 1/3 2.0% Equity Investors 12.0% none 12.0% 1/3 4.0% Estimated WACC for Total Assets 6.0% In a competitive environment, the average firm’s ROA should be close to the cost of financing total assets. Indeed, as we saw in class, average ROA’s mean revert to 6%. 3. RONA The same argument goes for returns on net asset. In this case, the denominator is total assets minus s/t liabilities. That is, we are interested in the returns to l/t debt and equity holders only. Therefore the WACC calculation is: Source of Financing Long term liabilities Pretax Cost of Financing 10.0% Effect of Tax Shield t=40% After-tax Cost of Financing 6.0% % Weight ½ Contribution to WACC 3.0% Equity Investors 12.0% none 12.0% ½ 6.0% Estimated WACC for Total Assets 9.0% In fact we find that in large samples average RONA is around 9% (PHB, p. 9-7). 4. ROE The capital base for ROE is capital provided by shareholders only. The earnings to this capital is therefore Net Income (that is, the earnings after we have paid interest and taxes). Moreover, the appropriate cost of this capital is the cost of financing by equity, which is approximately 12% to 13% in the U.S. (based on a market premium of 5 to 6 percent and a riskless rate of 6 to 7 percent -– see, for example the Copeland et. Lectures 4 through 6 Page 15 of 15