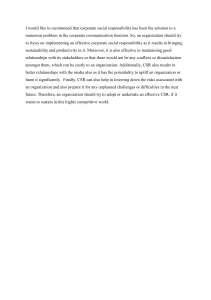

ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 ANNUAL REVIEWS 0:0 Further Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. Click here for quick links to Annual Reviews content online, including: • Other articles in this volume • Top cited articles • Top downloaded articles • Our comprehensive search The New Corporate Social Responsibility Graeme Auld,1 Steven Bernstein,2 and Benjamin Cashore1 1 School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06511; email: graeme.auld@yale.edu, benjamin.cashore@yale.edu 2 Department of Political Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 3K7, email: steven.bernstein@utoronto.ca Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008. 33:413–35 Key Words First published online as a Review in Advance on August 1, 2008 codes of conduct, environmental management, environmental standards, legitimacy, NSMD governance, partnerships The Annual Review of Environment and Resources is online at environ.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.32.053006.141106 c 2008 by Annual Reviews. Copyright All rights reserved 1543-5938/08/1121-0413$20.00 Abstract The last half decade has witnessed a remarkable resurgence of attention among practitioners and scholars to understanding the ability of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to address environmental and social problems. Although significant advances have been made, assessing the forms, types, and impacts on intended objectives is impeded by the conflation of distinct phenomena, which has created misunderstandings about why firms support CSR, and the implications of this support, or lack thereof, for the potential effectiveness of innovative policy options. As a corrective, we offer seven categories that distinguish efforts promoting learning and stakeholder engagement from those requiring direct on-the-ground behavior changes. Better accounting for these differences is critical for promoting a research agenda that focuses on the evolutionary nature of CSR innovations, including whether specific forms are likely to yield marginal or transformative results. 413 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 Contents Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. 1. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2. CONCEPTUAL AND ANALYTIC CHALLENGES . . . . . . 3. TAXONOMIC CATEGORIES OF THE NEW CSR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.1. Individual Firm Endeavors . . . . . 3.2. Firm-NGO Partnerships . . . . . . . 3.3. Public-Private Partnerships . . . . 3.4. Information Approaches . . . . . . . 3.5. Environmental Management Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.6. Industry Association Codes of Conduct . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.7. Nonstate Market-Driven (Private-Sector Hard Law) . . . . . . 4. WHY FIRMS SUPPORT CSR: THE BENEFITS OF REFINED CLASSIFICATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5. TOWARD AN EVOLUTIONARY SENSITIVE CSR PROJECT . . . . . . 5.1. The Evolutionary Logic and the Conundrum . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.2. Phase I: Initiation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.3. Phase II: Gaining Widespread Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6. CONCLUSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 414 415 416 417 420 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 428 429 1. INTRODUCTION In the past 15 years, an array of stakeholders have turned to firms, rather than governments, to address enduring environmental problems including forest degradation, fisheries depletion, mining destruction, and even climate change, as well as social problems including workers’ and human rights. As a result, a wide range of tactics, including boycott campaigns, social and ecolabeling, and environmental certification, have been used to appeal directly to firms to improve their environmental management procedures and performance as well as their treatment of workers and the impacts of their activities in the communities in which they operate. These efforts to pro414 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore mote what is generally known as corporate social responsibility (CSR) (1) have increasingly attracted the interest of a wide range of scholars within political science, economics, sociology, anthropology, and geography. Several factors have coincided to explain this renewed interest in CSR among both practitioners and scholars. These include the ineffectiveness, to date, of many governmental and intergovernmental processes (2), accelerating economic globalization, which has placed special attention on transnational or global firms (3), and general interest in pursuing innovative “smart regulation” (4) that, supporters argue, would encourage entrepreneurial innovation (5, 6). Does CSR have the potential to address enduring environmental and social problems? We argue that the greatest challenge for CSR scholarship in answering this question is the conflation of very different phenomena under the rubric of CSR (7). To further advance our understanding of the possibilities and limits of CSR to transform market behavior and ultimately be a significant force for social and environmental change, we must more precisely define the particular phenomenon being assessed. The general failure to define and delineate types of CSR has led to misunderstandings surrounding why firms support it, and the implications of this support, or lack thereof, for the potential of innovative policy mechanisms to be effective where government policy has been inadequate or absent. Furthermore, this gap has significantly limited the ability to address arguably the most important question facing CSR scholarship: whether and how CSR innovations might evolve to become enduring and meaningful arenas for the promotion of environmentally and socially responsible behavior? We advance this argument in four analytic steps. First, we review key definitional and conceptual challenges facing research on CSR. We delineate different phenomena that fall under the CSR label and the different expectations practitioners and scholars have regarding such efforts. In particular, we review scholarly assessments of whether these efforts Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 promote learning and stakeholder engagement, which may have indirect impacts on behavioral change, or directly require specific on-theground behaviors. Second, drawing on these distinctions, we identify taxonomic categories under which scholars can place their particular research projects. A third section justifies why we ought to be sensitive to these differences, especially because particular CSR programs can change over time—moving from one taxonomic category to another. A fourth section reviews the conceptual, methodological, and theoretical challenges in understanding and researching such an evolution. We conclude by assessing what our review means for the next generation of CSR, and the potential of CSR to become an effective tool within domestic and global environmental and social governance. We are interested not only in what CSR initiatives have done, but also their transformative potential in the global marketplace. In other words, the next stage for CSR research is to shift from a debate on whether CSR makes a difference in particular cases to whether, and what types of, CSR hold promise as alternative forms of environmental and social regulation. 2. CONCEPTUAL AND ANALYTIC CHALLENGES Any effort to assess the burgeoning interest in CSR should begin with two important conceptual distinctions: between the old and new CSR and between win-win and win-lose CSR efforts. On the first distinction, Vogel (1) notes that, although CSR efforts have significant historical roots, older efforts largely focused on corporate philanthropic activities that usually had little to do with the firm’s core business practices. These efforts were spurred particularly in the United States by favorable tax laws and remain important in American life. They have led to the creation of the Carnegie libraries and socially and environmentally active foundations, including those of the Ford and Rockefeller Brothers, and, more recently, Bill and Melinda Gates’ foundation, whose charitable contribu- tions have nothing to do with addressing any environmental or social challenges within the software and computing industries. In contrast, the new CSR is squarely focused on internalizing a firm’s negative externalities. Instead of explicitly or implicitly diverting attention from an environmental or social concern arising from a firm’s core business activity, the new CSR occurs when firm officials address such issues directly. Hence, corporate image builders applying the new CSR seek to show that their firm is actively promoting social and environmental standards that regulate or alter their core practices, often in an attempt to show they are ahead of their competitors. Supporters argue that such dynamics, if successful, can lead to a “race to the top” as firms compete for the title of being the most environmentally and socially responsible. The second analytic distinction—between situations in which CSR is win-win or winlose from the firm’s perspective—arises because the new CSR imposes social and environmental requirements/burdens on profit-maximizing firms. In win-win situations, solutions are available internally, where improvements in practices are also profitable. In win-lose cases, however, immediately available internal solutions are unprofitable or otherwise harmful to the firm’s survival or success in the marketplace. Win-lose situations therefore require the creation of some external economic benefit or change in the competitive environment to offset the environmental and social costs of new or altered practices. If neither profitable internal changes nor external economic benefits are available, a profit-maximizing firm undertaking the new CSR will, over time, either suffer comparative disadvantage vis-à-vis nonparticipating firms by losing money, or the self imposed requirements will be marginal rather than transformative. Many of today’s examples, heralded by firms and advocates, fit under the immediate win-win category. For instance, one explanation for the plethora of firms now engaged in voluntary greenhouse gas emissions reductions is that they will realize, if successful, www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 415 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 economic gains and provide environmental benefits. Firms often attempt to unlock, or advocate, these win-win scenarios in two ways. First, they may collaborate with environmental organizations or champion multistakeholder learning dialogues to assist them in their efforts. Such approaches can save firms’ time and resources, as the nongovernmental organization (NGO) provides what otherwise would have imposed internal cost. Their purpose, in these cases, is to uncover new business practices as well as build trust among potential critics of the firm’s intentions or commitment. Second, firms seek and apply advances in new technological innovations (6). Predictably, fewer examples of win-lose cases are available because purposeful internal behavioral change, in the long run, requires some type of countervailing economic benefit (whether abstract or direct) to justify cost impositions. Profit-maximizing behavior, and the interests of shareholders, mandates that firms avoid a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors. No amount of good will or leadership can change this logic (8). Although successful CSR efforts in these win-lose situations are, understandably, more limited than other forms of CSR, we argue that they deserve the most sustained attention because if they emerge as enduring and purposeful features of the marketplace they hold the greatest transformative potential. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 3. TAXONOMIC CATEGORIES OF THE NEW CSR We focus our review on the new CSR because its goal is to direct and require particular environmentally and socially responsible behavior—an activity that until recently was something in the ambit of governments. As Andrews (9) argues, and as most working on CSR agree (10–15), the burden of proof on CSR advocates is “to demonstrate how their proposals will in fact achieve equal or better results than government regulations” (9, p. 179). To shed light on differences among CSR initiatives in pursuing these goals, we identify seven categories of initiatives 416 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore and the logic of change underlying each. We pay particular attention to whether their immediate and long-term aims are to encourage broad-based stakeholder learning and/or direct prescriptive behavior on the ground. Following that discussion, we assess the potential transformative capacity of these different categories of CSR in win-lose situations. Our classification and evolutionary emphasis departs from Baron’s (16) approach in that, by definition, CSR must go beyond market demands, and also from much of the remaining literature’s baseline that to count as CSR, it must promote behavior beyond compliance with existing laws (8; 11, p. 108; 17–19). Although there is an elegance and tractability to these approaches, we employ an alternative for three reasons. First, limiting CSR to only those innovations that do not produce market demands eliminates some of the most important and innovative efforts to promote stewardship through the marketplace. Second, if we focused solely on beyond-compliance initiatives, because governments often change their rules, a firm could lose its CSR status even if it did not change any internal commitments. Similarly, if a large firm operates in different political jurisdictions, a corporate environmental strategy may be at once beyond compliance in some jurisdictions but below compliance in others. In these cases, the same strategy would be simultaneously classified as both an example of CSR and not CSR. Third, it is, as we show below, a conceptual mistake to equate an incompliance firm, which undertakes a beyond compliance CSR strategy solely as a means to reduce the threat of impending governmental regulations, with a firm which undertakes a CSR strategy because it wants to find a way to address an environmental or social challenge. To be sure, both strategies could lead to important changes in policies, yet their underlying motivations could reveal quite distinct reasons for support and therefore longer-term prospects of transformation (20, p. 325; 21). Although a static definition may be easy to operationalize, it can limit understanding of dynamic change within firms, the interaction of Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 CSR choices with the broader public policy arena and organizational fields (see, e.g., 22), and the motivations for support. These factors are the most important for understanding the sources of behavioral change/commitment and whether and how the CSR innovation might lead to direct change or to learning that ultimately is influential through other policy innovations and/or governmental processes. Our classification, rooted in the above distinctions, discerns seven ideal types of CSR innovations: individual firm efforts; individual firm and individual NGO agreements; publicprivate partnerships; information-based approaches; environmental management systems (EMSs); industry association corporate codes of conduct, and private-sector hard law known as nonstate market-driven (NSMD) governance. Their delineation is useful, as Table 1 reveals, in identifying differences in origins, internal compliance incentives, interactions with statecentered authority, internal governance mechanisms, policy approach/scope, and enforcement mechanisms. We develop these seven categories as ideal types and recognize that not all examples fit easily into a category. Nonetheless, we argue that disentangling these differences is critical to addressing questions about effectiveness—the ultimate concern of most analyses—including what firm support means for direct impacts (both short- and long-term) and longer-term transformation via learning across stakeholders. 3.1. Individual Firm Endeavors Individual firm endeavors are the most common and widely studied form of the new CSR, which focuses on strategies of individual firms to undertake environmentally and socially responsible behavior. Scores of practitioner conferences have been devoted to understanding the business case for CSR and the positive economic impacts that can accrue to such firms. Similarly, researchers invest great effort to assess the links between CSR initiatives and financial performance (23). Scholarly journals are replete with work detailing the origins, ongoing development, and success or failure in a broader sense of internal CSR initiatives at major multinational firms, including Wal-Mart (24), Chiquita Brands International (25), Ikea (26), Nike (27), food retailers in general (28, 29), and specific ones such as Unilever (30), among others (31, 32). Providing environmental or sustainability reports (33), supporting ecolabeling, promoting health and safety for employees, and ensuring fair working conditions in the factories that produce their products comprise some of the efforts firms employ. A second, less-examined aspect of firm CSR initiatives concerns those proactive efforts to uncover and pursue win-win solutions or turn what appear to be win-loss situations in the short term into longer-term win-win situations. That is, some firms have, as Esty & Winston (6) reveal, been proactive in developing new green and socially responsible markets that, by their very nature, embed a stewardship ethic (34). These include Toyota’s proactive decision to gamble on creating fuel-efficient and green hybrid cars, which stands in contrast to Ford’s ultimately uneconomic decision to focus on the declining SUV market. Similarly, GE’s decision to promote wind and solar technology is an effort to change the very market demand upon which it depends. Although such technological innovations are not considered CSR by some (16), we see this as a mistake because, arguably, any effort to find or create win-win solutions will have far greater and enduring impacts than abstract, and unenforceable, commitments to costly behavioral changes. A search for these technological win-win activities could mitigate, for example, suboptimal technologies (35). In general, then, firm level innovations, by relying on internal firm decisions, are characterized (Table 1) by the absence of direct governmental requirements on policy-making processes internal to the firm, although the shadow of the state is never completely absent. Compliance incentives tend to accrue abstractly from the firm’s interest in developing a social license to operate (34, 36), from green markets (34, 37) or technological advances that reduce www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility Environmental management system (EMS): a structured framework of procedures to implement and achieve a company’s environmental performance targets and goals Nonstate marketdriven (NSMD) governance: a special case of private governance where states do not implicitly or explicitly provide compliance incentives 417 418 Auld All state-based authority and intergovernmental agreements The state The state Central Who creates the rules? Compliance incentives Role of state Government traditional Traditional · Bernstein · Cashore Variable Can require or encourage State(s) (sometimes require) Markets (public shaming) State does not use its sovereign authority to directly require adherence to rules Transnational supply chain Members of the certification body Usually environmental, social and business interests Forest Stewardship Council, Marine Stewardship Council, Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International State(s) delegate and/or share State(s), either explicitly or implicitly Agreed upon by participating governmental and nongovernmental actors EPA star preferred treatment U.S. voluntary standards program (state in background) Global Compact Public/private partnerships In background Helps facilitate intergovernmental agreements Public image Win-win learning Private bodies Range of stakeholders but industry dominated Implicit links to intergovernmental efforts, such as World Trade Organization Often in shadows Benefits in membership and public image The trade association Responsible Care, Equator Principles, American Forest and Paper Association’s Sustainable Forestry Initiative, Australian Forestry Standard of conduct systems International Organisation for Standardization (ISO), ecomanagement and audit scheme Industry associations codes Environmental management The new corporate social responsibility Often in shadows Scrutiny of firm activities by public, stakeholders, and shareholders The firm Thousands of examples: Starbucks CAFÉ standards, McDonald’s sustainability Individual firms 16 September 2008 Government, industry, and/or other stakeholders Global Reporting Initiative Information approaches Nonstate market driven (private sector hard law) Distinguishing the new corporate social responsibility ARI Examples Table 1 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 0:0 Courts, police Wide ranging Historically focused on command and control Policy Approach Moral suasion None Variable Prescriptive Compliance must be verified Institutionalized procedures for ongoing policy participation from diverse societal and stakeholder groups Consensual Scope can be wide ranging Varies, often turn first to voluntary approaches Ranges from closed communities to wide ranging stakeholder participation Focuses on management systems Does not contain on-the-ground requirements Usually third party certification of broad principles Variable including business-dominated and/or multistakeholder approaches Emphasizes broad goals Flexible approach Fewer on-the-ground requirements Association oversight varies Tends not to be as extensive Limited to members of regulated group Varies Internal Often relies on self-declarations Internal to the firm 16 September 2008 Enforcement Varies across states ARI Governance Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 0:0 www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 419 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. costs and enhance profits (34), or from a desire to have a first-mover advantage (38). In this CSR category, then, there are no externally imposed prescriptive requirements to which a firm must adhere, and the firm controls the processes and policies it develops. However, because these efforts almost always involve interacting with stakeholders, we would expect such an approach to promote learning and to offer the potential to uncover win-win solutions. 3.2. Firm-NGO Partnerships In this category, firms initiate, or are involved in, partnerships with other stakeholders. Partnerships come generally in two forms: (a) ones in which they partner with environmental or social groups to address environmental or social issues associated with their operations (39, 40), which is the focus of this discussion; or (b) a public-private partnership in which firms, governments, and NGOs all interact toward some common goal, which we categorize separately in section 3.3. Environmental Defense and Conservation International, and are prominent U.S. examples of organizations that have partnered with companies such as McDonalds, Starbucks, and FedEx, among others (41, 42). The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is also a frequent partnering NGO that has worked with Unilever (43) and Domtar (44), for instance, and has developed, in the forestry sector, partnership arrangements with hundreds of forestry product buyers and suppliers in more than 30 countries that aim to encourage shifts to the supply and demand of sustainable forest products (45). Such partnerships can be important for both unlocking indirect learning processes and promoting direct specific requirements. There is little question that when NGOs and firms discuss issues they almost always uncover misunderstandings about how things work, which led NGOs to champion a course of action that might not have had the effects they were seeking. Such partnerships can also create outside benefits, albeit abstract, because the public is 420 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore more likely to accept a project with NGO participation than one in which firms act alone (46, 47). We expect perceptions of this outside benefit to largely determine the size and nature of the steps firms can undertake. 3.3. Public-Private Partnerships In contrast to private-private collaborations between firms and a counterpart NGO, publicprivate partnerships involve firms as part of a broader community of interests in which government, business, environmental, and social stakeholders interact around solving a given problem (48). Partnerships come in many forms. They can involve coordination to address rule or standard setting, implementation, or service provision, where the relationship (from the state’s perspective) can be classified as co-optation, delegation, coregulation, or self-regulation in the shadow of hierarchy (49). Co-optation involves state consultation with private actors. Delegation occurs when states or intergovernmental organizations give private actors responsibilities over governance functions. Coregulation involves true joint decisionmaking between the state and private actors. Finally, self-regulation in the shadow of a hierarchy captures cases where private actors selfregulate to avoid or reduce threats of state intervention (49). Public-private partnerships also exist at the local, national, and international levels (49– 51). They can include efforts, organized by a municipality and local companies, to provide clean water to impoverished communities (52) or provide AIDS-stricken communities with access to drugs, as in the case of the UN HIV/AIDS effort (53, 54). In this latter example, the United Nations, through the Global Health Initiative, provides an arena and some resources for engaging drug companies in an effort to bring impoverished communities health care treatments that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive and out of reach. At the domestic level, a prominent example is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) effort to give incentives to green firms Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 in the form of reduced regulatory oversight through such programs as the Common Sense Initiative and Project XL (19, 55–57). Here, the focus is on developing a more efficient means for enforcing costly legislation (19, 58). In other cases, programs can explicitly eschew regulatory relief. The 33/50 Program, initiated by the EPA in 1992 to reduce releases of 17 key toxic substances by 33% by 1993 and 50% by 1995, was structured without provisions for relaxed regulatory oversight (59). Another example is the U.S. Department of Energy’s Climate Challenge Program, initiated in 1994 to encourage electric utilities to reduce or offset greenhouse gas emissions (55). Indeed, on the basis of a review of 60 extant U.S. public voluntary programs, Lyon & Maxwell (14) uncover that few offer explicit regulatory relief. Instead, the majority aim to disseminate information on best practices or technologies and to give companies public recognition of their beyondcompliance behavior. In these cases, which were initiated under the Clinton administration (60) but have since been further favored under the George W. Bush administration, the state is directly involved in providing firms the option of pursuing such efforts, with the implicit knowledge that refusal by firms to participate will create pressure on the state to pursue a more traditional command and control or regulatory approach (61). In all of these cases, the state is directly or indirectly involved, either as facilitator or financial provider, but never as the sole decision maker. Instead, stakeholders participate in joint decision making, with a focus on problem alleviation and the alignment of strategic interests. The type of problem addressed varies widely. Hence, the AIDS example is focused on saving lives, whereas the UN Global Compact, which brings together firms who agree to promote its principles for global corporate behavior, is more abstract and emphasizes norms of corporate responsibility (62, 63). Although diverse, we would expect public-private partnerships to be effective when they explicitly draw on state authority to require behavior and/or lead to innovative approaches that the firm, by itself, could not have uncovered and/or implemented on its own. 3.4. Information Approaches Another important feature of many CSR efforts focuses on the provision of information related to a firm’s behavior. Information-suppression and -disclosure policies and voluntary labeling programs are means by which governments encourage behavioral change through the control of information (64). The EPA, for instance, created the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) as a provision of the 1986 Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, which mandated public access to information on release levels for hundreds of toxic substances emitted by U.S. industrial facilities (65). Later, in 1991, as discussed above, it launched the 33/50 Program as a voluntary beyond-compliance program intended to expedite emission reductions of certain TRI toxins (8, 66, 67). More recently, certain U.S. states made it mandatory for power utilities to disclose environmental information on marketing as well as product-sales information for utility customers (68), and amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act required water suppliers to disclose information on contaminants (65). Again, Lyon & Maxwell’s work (14) illustrates the prevalence of information approaches in the suite of recent U.S. public voluntary programs. Outside the United States, information policies have also grown in popularity. The German ecolabel was first introduced in 1978, followed by similar programs in the Netherlands, Austria, France, and the EU as a whole (61, 69). Canada, Australia, and the EU have also adopted information-disclosure requirements on toxics similar to those of the U.S. TRI (70). Information approaches carry their own logic of effectiveness. The idea behind them is that, by making environmental performance more transparent (and hence shaming or rewarding through abstract public consternation or support), an economic logic exists, which may shift behavior by eliminating the most detrimental practices, products, or by-products www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 421 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS): a European Union program to reward and recognize companies that go beyond minimum legal compliance and continuously improve their environmental performance ISO: International Organization for Standardization 0:0 of production in favor of more benign ones. They can also lead to learning among stakeholders about corporate practices, facilitating decisions on the basis of more scientific understandings than (often incorrect) perceptions. As Rosenau (51, p. 12) notes, virtually all of them involve “close collaboration and the combination of the strengths of both the private sector (more competitive and efficient) and the public sector (responsibility and accountability vis-àvis society).” Underlying this emphasis on transparency, rather than prescriptive requirements, is the hypothesis that global firms will be shamed into doing the right thing, or they will risk losing markets if they fail to act. Governments belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have adopted this approach (61, 69, 70), but it also exists transnationally in a CSR/voluntary format through the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (71, 72). Firms, participating in the GRI, voluntarily report the environmental and social impacts of their activities. In these cases, the intergovernmental system is also in the shadows, but the reporting rules are developed by stakeholder members of the GRI, with considerable discretion given to individual firms. Currently, compliance mechanisms tend to be tied to the size of the firm, i.e., larger firms can be more easily shamed or targeted, whereas smaller firms are often shielded from such scrutiny. 3.5. Environmental Management Systems A fifth category is the adoption of externally imposed criteria about how to manage a firm’s internal approaches to environmental and social stewardship. This form of CSR allows firms to decide which behaviors they will adopt and focus on the win-win benefits that accrue from learning about how to develop their EMSs. Firms that adopt an EMS also may expect to gain the indirect benefit of the positive image that might accrue from society. The two most prominent examples of EMSs are Europe’s Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) 422 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14001 procedures for environmental management (18, 73). Industry and state delegates have historically negotiated ISO standards while incrementally increasing access to a range of other stakeholders (74). ISO is formally an NGO and provides certification of firms for development of internal processes. Although it does provide for third-party certification, and hence is distinct from self-initiated processes delineated above, its focus on systems, rather than behavioral on-the-ground requirements, provides a more complex picture as to whether support is an example of a firm being proactive or is attempting to gain cover from more prescriptive (and costly) requirements. ISO’s EMSs have been commonly and improperly confused with private-sector hard law systems. Even though firms are audited for following their own EMSs, ISO does not require any particular on-the-ground changes. It requires only continual improvement from the baseline of the company’s own specified targets. We also note that the increasing interest in CSR has now led ISO to develop a standard for social responsibility (to be published in 2008 as ISO 26000). This includes multistakeholder input, but unlike other ISO standards, it will have no procedural or on-the-ground requirements (only voluntary guidelines), and there will be no procedure for pursuing third-party certification (75, 76). EMSs have been strongly promoted because they often lead to learning among officials within a firm. That is, an EMS often leads to the identification of obsolete or inefficient practices that might simultaneously improve the bottom line and environmental performance. In addition, to the extent that goodwill is created, there may be an additional outside benefit that would permit the firm to implement internal costs consistent with the outside benefit. At the same time, we expect that confusion between EMS procedural requirements and the hard law systems below may actually lead to less effectiveness. That is, scholarship must carefully assess whether EMSs are used as a way to avoid specific behavioral requirements to ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. address an environmental problem or to obscure what are actually limited efforts. This means that correlational statistical analyses that focus on adoption of standards, by themselves, are insufficient. They must exist alongside indepth historical case studies that place attention not only on firm adherence to particular policies but also to the behavioral requirements that follow from such a course of action. 3.6. Industry Association Codes of Conduct Attempts by industry associations to establish industry-wide codes of conduct to which its members commit to adhere fall under this category (77–80). Examples include the chemical industry’s voluntary Responsible Care Program (4, pp. 137–266, 81), the Sustainable Forestry Initiative in the United States and Canada (82), the recent Cement Sustainability Initiative supported by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, and a code for responsible fisheries practices supported by the US-based Responsible Fisheries Society (83, 84), among others (see 61, 80). Unlike the firm-level activities described above, industry-wide initiatives build collective efforts to improve CSR practices across firms. Hence, they contend with interfirm as well as intrafirm politics. Many studies examine these politics to understand the origins of codes across sectors and generally find them emerging in industries where companies hold collective reputations (a bad image of the industry impacts all companies, regardless of their individual performance) (81, 85) and sell primary or intermediary goods, not end-consumer goods (4, p. 161; 86; 87). More recently, however, industry-wide initiatives have formed that contradict this pattern. The Common Code for the Coffee Community, for instance, serves as a baseline standard for social and environmental practices in coffee production, trade, and roasting, and it has enlisted many of the world’s largest coffee roasters (88–90). Recent work by King (91) proposes explanations for these patterns on the basis of transaction cost theory, but it remains to be explained why sector-wide initiatives pervade certain sectors and not others. Movement toward Responsible Care, one of the first industry codes, began in the late 1970s within the Canadian Chemical Producer Association. Focusing events, including the Love Canal and Union Carbide’s Bhopal disaster, served by 1984 to transform a policy statement to a condition of membership, an effort by Canadian producers to deflect threats of government intervention (92). This program includes no formal role for social or environmental groups. Although industry association programs are a step beyond firm-level CSR initiatives, those that leave control to their business members and do not engage outside stakeholders are distinct from full-fledged thirdparty standard setting. In particular, industrydominated initiatives do not create an adaptive governance arena that mediates among divergent viewpoints or otherwise mitigates power struggles. The Equator Principles represent another emerging example of a principle-setting exercise. These principles provide the banking industry with a “framework for addressing environmental and social risks in project financing” (93). Firms sign onto the principles voluntarily and signal their support through self-declarations (94, pp. 121–44; 95). Some codes of conduct are less easily classified, especially those that include governments in the formulation of rules and therefore have some characteristics of public-private partnerships. We place them in this category nonetheless because their operational features and voluntary character make them analytically similar to industry association codes. For example, the OECD’s Guidelines for International Investment and Multinational Enterprises (revised in 2000) encourages a wide range of good practices and establishes National Contact Points to promote them, but the standards are voluntary even for those firms that sign on (96, 97). The most prominent sustainability information mechanism, the Global Reporting Initiative, although neither an industry association nor public-private partnership, fits the same www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 423 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. FSC: Forest Stewardship Council 0:0 pattern (98). Highly touted as a mechanism to operationalize transparency and accountability for initiatives such as the OECD guidelines and Global Compact, it simply provides guidelines for organizations to report their pollution levels and other sustainability measures. Hence, codes of conduct can be important forces for unleashing learning across stakeholders and for engaging with the public and organized interests about their stewardship. They are, however, not the place to identify and produce specific behavioral requirements to which firms must adhere, nor adaptive arenas for multistakeholder decision making. 3.7. Nonstate Market-Driven (Private-Sector Hard Law) This unique type of CSR institution differs fundamentally from the above efforts because it is about creating enduring and prescriptive hard law (i.e., it sets mandatory behavioral requirements to which firms must adhere) in the private sector. Although legal theory, and especially international legal theory, might find this characterization oxymoronic because nonstate forms of governance are defined as soft law rather than hard law (99), we use the term because this form of CSR creates obligations and rests on a sense of legitimacy more akin to public hard law than declaratory or private soft law (which sets abstract goals to which firms and other actors are encouraged to comply). Elsewhere, Cashore (100), Cashore et al. (101) and Bernstein & Cashore (102), labeled this phenomenon NSMD on the basis of their work on forest certification and the proliferation of other third-party certification systems that have emerged over the past 15 years. Five key features distinguish NSMD governance from other forms of public and private authority reviewed above. The most important feature of NSMD governance is that, in general, the state does not provide implicit, or explicit, compliance incentives. Rather, a private organization develops rules designed for achieving preestablished objectives (sustainable forestry, in the case of forest certification). A 424 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore second feature is that its institutions constitute governing arenas in which adaptation, inclusion, and learning occurs over time and across diverse stakeholders. The founders of NSMD approaches, including forest certification, justify this governance structure because they are more democratic, open, and transparent than the client-oriented public policy networks (i.e., where public authorities have a close relationship to clients in the private sector that they govern) they seek to replace. A third key feature is that these systems govern within a reconstituted “global public domain” (62), in which, as Ruggie describes it, states are “embedded in a broader, albeit still thin and partial, institutionalized arena concerned with the production of global public goods” (62, p. 500). Seeing the global public domain as no longer only the purview of states supports our position that these attempts to govern the private sector largely independent of state authority can still be viewed as hard law. To achieve global public goods, these systems require profit-maximizing firms to undertake potentially costly reforms, which they otherwise would not pursue, for the potential of longer-term collective (and possibly individual) benefits. This distinguishes NSMD systems from other arenas of private authority, such as business coordination over technological developments (the original reason for the creation of the ISO), that can be explained by profitseeking behavior and through which reduction of business costs is the ultimate objective. The fourth key feature is that authority is granted through the market’s supply chain. In the case of forest certification, the global Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which has widespread support from many of the world’s leading environmental groups, and FSC competitors, initiated by forest owners and industry associations, promote and champion their versions of sustainable forest management by focusing on forest products’ customers. They attempt to convince consumers and producers along the supply chain to support and demand that their supplies come from certified forests (103; 104, pp. 42, 43; 105; 106). Landowners Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 may respond to incentives, such as product price premium or increased market access, whereas environmental organizations may act through boycotts and other direct action initiatives. These forces convince large retailers, such as B&Q and Home Depot, to adopt purchasing policies favoring the FSC, thus placing more direct economic pressure on forest managers and landowners. The fifth key feature of NSMD governance is the existence of verification procedures designed to ensure that the regulated entity actually meets the stated standards. Verification is important because it provides the validation necessary for certification programs to achieve legitimacy, as certified products are then demanded and consumed along the market’s supply chain. This distinguishes NSMD systems from many other forms of CSR, noted above, that require limited or no outside monitoring (4, pp. 137–266). Buoyed by the forestry example, certification systems have proliferated in other sectors. These include the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, which, as of 1997, coordinated under one system national fair trade labeling initiatives that were all, in their respective national markets, aiming to ameliorate the conditions of poor and marginalized producers in the developing world by improving the terms of trade for their products. Fair trade now covers a diverse range of internationally traded commodities and specialized goods including coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, bananas, rice, fresh fruit, juice, honey, vanilla, nuts and oilseeds, cotton, sports balls, flowers, and wine (107). Similarly, Social Accountability International, initiated by the nonprofit Council on Economic Priorities to reduce sweatshop labor practices, developed into a system that monitors individual companies according to specified social criteria, including child labor and worker safety (108–111). The FSC model explicitly inspired the Marine Stewardship Council governing wild-capture fisheries management (112) and the Sustainable Tourism Stewardship Council, among others (113). Emergent umbrella systems include the International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labeling Alliance, which was created to develop agreement on best practices for any certification system (114, 115). The NSMD system is the category of CSR that most directly requires specific courses of action, but also simultaneously engages a variety of firms, NGOs, and other stakeholders in a range of learning efforts. Thus, NSMD deserves more sustained focus and assessment of its short-, medium-, and long-term potential to transform markets and, ultimately, effectively address environmental and social problems. 4. WHY FIRMS SUPPORT CSR: THE BENEFITS OF REFINED CLASSIFICATION The need for a more refined classification of CSR initiatives is borne out by the research on its effects. A core finding is that both the type of initiative and the context in which firms are motivated to support CSR play significant roles in determining the strength and kind of effects CSR has. For example, researchers applying both large-N studies (85, 116) and case research (117) find that when specific environmental standards, third-party oversight, and sanctions are absent, firm support does not tend to equate with on-the-ground changes in practices. For example, in an early examination of Responsible Care, King & Lenox (85) found no aggregate evidence that the program led members to accelerate their pollution reduction relative to nonmembers. Indeed, the opposite occurred; nonmembers improved faster than members. Even where third-party oversight is present, as is the case with ISO 14001, Potoski & Prakash (118) found that facilities with a moderate level of regulatory compliance, measured against their peers, were most likely to participate. Those with low or high levels of compliance were less likely to join. However, those that joined did improve their environmental performance, a result in contrast to King & Lenox’s (85) findings noted above. Additional analysis of design features of industry codes of conduct emphasize that small or federated www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 425 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 systems are better tooled to ensure effective compliance (119), particularly because small groups are better able to monitor and sanction members. Forces, or institutional pressures, outside a given initiative are also important determinants of effectiveness. Pressure from stakeholders and threats from regulators serve to motivate voluntary participation in CSR initiatives, even if they include sanctioning mechanisms that overcome the poor performance-participation correlation mentioned above (120). The formal education and environmental expertise of a chief executive officer also correlates with participation (121), illustrating the importance of internal company factors such as organization culture (8, 122). A sector with close business-tobusiness relations—where companies buy and sell to each other—also enhances the potential for effectiveness (10, 123). Within specific policy issue areas, authors argue for or against the usefulness of CSR activities in addressing underlying public policy problems. For water and energy sectors, for instance, concerns have been raised about voluntary CSR initiatives owing to the vital importance of these resources and the often-limited capacity of governments to control corporate involvement (124). Conversely, case studies have identified successful examples of connections between impoverished producers and niche markets for particular products. In these cases, marketing ethical or environmentally sound products can make a limited difference (125). Other research has examined participation across industry-, government-, and NGOsponsored voluntary programs to assess differences in the diversity of stakeholders’ participation (56). At the global level, studies uncover how particular CSR initiatives have built-in biases against particular stakeholders, e.g., those from the developing world (74, 126). The limited attention to developing-world perspectives also means that power imbalances between the poor and corporations are overlooked, leading to accountability problems with existing CSR initiatives (127). Other analyses have also em- Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 426 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore phasized the limited potential of CSR as a tool for addressing poverty (128). Following in this vein, CSR has been distinguished from corporate accountability in an effort to emphasize that both are required for corporations to have any potentially beneficial effects on development. However, even in the best case, broad changes in the global economy are considered necessary for real changes to occur (129). Some place hope in the role of NGOs and so-called antiglobalization or global justice movements as the agents that would drive a major shift toward regulating activities of transnational corporations (94, 130). As a response to these problems and criticisms, scholars have offered new frameworks for improving the sustainability of CSR operations in the developing world (131). Multilateral development institutions are showing increasing interest in being drivers of global CSR and its coordination to foster improved corporate accountability (132). Supporters of CSR are also looking to these institutions to play a role in enhancing developing country governments’ capacity (133), a crucial condition for CSR to be effective. Finally, some authors argue for and/or show how CSR can benefit developing countries, either alone or in combination with traditional development programs and projects. First, CSR approaches could be usefully adopted by NGOs and donors working on development issues (134). Second, working with communities to develop social capital is seen as a win-win for corporations operating in the developing world (135). 5. TOWARD AN EVOLUTIONARY SENSITIVE CSR PROJECT Another benefit of a more refined categorization of CSR is that it highlights, and allows analysis of, how particular programs can evolve, adapt, and change. For example, in 2005 the Responsible Care program created a third-party monitoring component in response to criticism, which moved it closer to the privatesector hard law model. Similarly, the Fair Labor Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 Association (FLA), spawned by the U.S. Apparel Industry Partnership, initially lacked welldeveloped mandatory standards or independent verification of compliance. But the FLA developed a mandatory third-party auditing system in 2002, which was implemented in 2003 (136) in response to competition with the Workers Rights Consortium, a group established to investigate and report labor code violations perpetrated by controversial factories (109, 137). Thus, it is important to note that organizations can change in response to external pressures. Evolution may occur through competition with other third-party certification systems. This competition can lead business associations that first initiated voluntary soft law codes of conduct to be ultimately spun off as independent organizations, for example, the American Forest and Paper Association’s voluntary code-of-practices program, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), initially developed in response to threats of regulation and the emergence of the FSC (86). Now the SFI’s nine-member board comprises onethird business, one-third academic, and onethird NGO members. Though the governing structure is more narrowly cast than the FSC model and tends to include relatively moderate civil society interests, the SFI example nicely illustrates the importance of assessing how governing arrangements can change. Although clearly giving more authority to industry than the FSC model, the SFI has adapted and included other nonfirm actors in ways that few would have predicted just a few years ago. Given these dynamics, what path ought CSR scholarship to take? Our answer also takes into account that any analysis of CSR efforts should assess not only existing impacts, but also the potential of CSR innovation if it were to fully institutionalize in a sector. The implications are important: Empirical work is critical but, by itself, is insufficient for understanding the implications of CSR. Rather, we need better theories about the evolutionary capacity of CSR initiatives to assess transformative capacity. A lack of such theory development, combined with a continuing focus only on the present and the past, inadvertently increases the risk that any practical advice offered from this type of scholarship may make recommendations that hamper, rather than improve, the potential of CSR to address enduring global, social, and environmental challenges. To illustrate the importance of such an approach, we briefly review Bernstein & Cashore’s (102) efforts to understand the evolution of the private-sector hard law form of CSR. Their framework delineates three phases through which initiative must move to achieve full-fledged political legitimacy. Our focus on an evolutionary framework moves beyond an emphasis solely on learning and technical fixes, which, as we argued above, can only make a difference in win-win situations. Instead, an evolutionary framework addresses ways in which win-lose situations might be transformed to win-win situations as a hard law system gains political legitimacy. By gaining legitimacy, they alter the firm’s cost-benefit calculations by transforming the marketplace environment. They facilitate the emergence of the external benefits and/or costs of inaction that shift situations from win-lose to win-win, which is ultimately necessary for CSR initiatives to succeed. 5.1. The Evolutionary Logic and the Conundrum NSMD systems exist within a suite of policy innovations that include corporate codes of conduct that pose few or no mandatory rules regarding on-the-ground behavioral changes, and where businesses dominate policy development. Given this, what types of support might firms be expected to grant NSMD systems? Drawing on Bernstein & Cashore (102) we discern two phases that NSMD certification systems pass through toward their hypothesized third and final phase of political legitimacy— in which members of the sector collectively agree to abide by the rules and procedures of the NSMD governance system or a common standard or set of standards across systems that operate in a particular sector. www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 427 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 5.2. Phase I: Initiation Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. What types of firms, whose operations are the target of a certification system, might be expected to join, at the outset, an NSMD certification? Moreover, why would any firm ever join these hard law programs? After all, in most sectors where NSMD certification is vying for support, there are also more flexible or nonprescriptive programs they could join instead, such as ISO 14001, the UN Global Compact or Responsible Care. Hence, on the basis of existing work, described above, there remains an important gap in our understanding of why firms seek to participate in NSMD hard law programs when they impose greater requirements than other CSR initiatives. Many firms would indeed balk at supporting such systems precisely because they would be viewed as imposing greater costs than benefits. Moreover, support translates to relinquishing their own authority to decide on what to do about environmental issues when more palatable voluntary alternatives are available that leave all, or a great deal of, discretion to individual firms. One would expect those firms operating close to, or at, the requirements of the certification system to be the first to join. Thus, at the initial phase, when an NSMD hard law initiative gains some degree of recognition, it creates a degree of abstract economic benefits, either because they provide a boycott shield or because membership will provide them environmental stewardship recognition in ways unavailable to other CSR programs. Likewise, firms that would have to undergo significant changes and costs to meet the requirements of the systems will be the last to join. This argument also begs the question of why some firms would already be practicing closer to the standards of an NSMD system? In almost all cases, the reason is public policy requirements, i.e., what traditional governmental regulations dictate about how firms must behave. When government regulations are the most prescriptive, and when certification rules do not deviate too far from required practices, the greatest support from firms can be expected. This does not mean that all firms operating under these 428 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore conditions will agree to join (because the costs of foregoing autonomy is uncertain), but it does mean the reverse is true. Those firms that are not highly regulated by governments and that compete with other nonregulated firms will be much less likely to support certification, as it could lead to their economic demise. During this initial phase, it is important to assess the evolving expectations of other members of the NSMD community as well, particularly environmental and social groups that joined in order to ameliorate a particular environmental resource use or social problem. One would expect such members to develop close community ties with those initial firms that have demonstrated that the rules of the program are indeed obtainable and to differentiate these firms as heroes from the villains,which have refused to participate. They also have an interest in highlighting, emphasizing, or exaggerating the marginal on-theground changes that do occur to justify the importance of their program. 5.3. Phase II: Gaining Widespread Support Given the expectation of limited uptake in phase I, how might NSMD hard law systems evolve to gain widespread support? Such support is necessary because any marginal improvements that occurred in Phase I will not, by definition, be adequate to address the core problems in a global sector for which NSMD systems were designed (whether it be mining, forestry, fisheries, coffee, and so on). How might NSMD certifications move to this second phase? The hurdles are immense and reveal a conundrum. First, to appeal to the firms that did not join in Phase I, certification programs must, in the absence of increased market incentives, relax their behavioral requirements. That is, moving to Phase II requires readjusting the cost-benefit calculations of firms that rejected membership during Phase I. Moreover, because of the chicken and egg problem in developing certified markets in which supply and demand must be in synchrony, market pressures Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 can only advance incrementally. Behavioral requirements may have to be lowered, albeit until markets are fully developed if Phase II is ever to be achieved. However, the lesson from environmental and social groups in Phase I is that firms can indeed meet the (relatively) high requirements. Over time, these environmental and social activists will want to demand an increase in standards. The challenge for those promoting NSMD certification systems is to overcome this conundrum. If it is not overcome, we would expect a significant degree of competition between the NSMD certification systems and the more palatable CSR alternatives. Whether and how this conundrum might be overcome is a key question facing students of CSR. Bernstein & Cashore (102) have offered an initial set of propositions that argue for greater attention on norm generation and community building. The point for this article is to illustrate how after isolating different phenomenon, conflated under CSR, a much more complex and dynamic picture emerges about how support for a particular taxonomic form is contingent upon, and interacts with, other CSR forms and existing governmental regulations. These interactions are critical to understanding whether and how CSR institutions might evolve to become enduring and purposeful forms of global authority. 6. CONCLUSIONS Do CSR efforts address enduring environmental and or sustainability challenges in ways that traditional governmental approaches have been unable to achieve? Are the impacts transformative or marginal? Do they provide interesting cases but fail to have widespread impact on the problems for which they were created? Or worse, are they best classified as an effort to escape governmental regulation, resulting in fewer behavioral changes than otherwise would have occurred? Here, we argue that to better address these questions, two primary tasks must be undertaken. First, clearly specify the policy innovation and assess its relationship to the problem for which it was created. Second, assess not only today’s impacts but the potential for affecting behavioral change at a later time. Such an approach requires not only developing correlations between support and impacts, but also building theory on the causal mechanisms and temporal logic of different CSR innovations. Arguably the most important efforts for making practical contributions are those that undertake greater and more sophisticated theoretical work. For these reasons, both scholars and practitioners must be neither preemptively Pollyannaish nor dismissive of CSR innovations. SUMMARY POINTS 1. A focus on what firm-focused efforts can do to ameliorate environmental and social problems requires, as Vogel (1) explains, recognizing the difference between the old and the new CSR. The former largely focuses on corporate philanthropic activity not directly linked to a firm’s core business practices. The latter focuses on internalizing the externalities produced by a firm’s core business activities 2. Distinguishing short-term win-win from win-lose outcomes helps separate motives for participation and possible futures for CSR efforts. Attention to both is important for different reasons. Seeking win-win technological solutions can help move us away from suboptimal technologies. With win-lose situations, the critical issue is assessing how and whether CSR initiatives can transform market conditions, over time, to make a win-lose into a win-win situation. www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 429 ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 3. We identify seven ideal types of CSR innovations: individual firm efforts, individual firm and individual NGO agreements, public-private partnerships, information-based approaches, environmental management systems (EMSs), industry association corporate codes of conduct, and private-sector hard law known in the scholarly literature as nonstate market-driven (NSMD) governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. 4. Our taxonomy permits the adoption of an evolutionary approach, which stands in contrast to beyond compliance definitions prevalent in existing CSR scholarship. We argue for a broader definition that captures dynamic changes within firms, the interaction of CSR choices with the broader public-policy environment and organizational fields, and the motivations for support. 5. These taxonomic categories are discussed according to whether their immediate and long-term aim is to encourage broad-based stakeholder learning and/or direct prescriptive behavior and assess the potential transformative capacity of these different categories of CSR in win-lose situations. FUTURE ISSUES 1. Future work in this area would be well served to carefully specify the policy innovation at hand and assess its relationship to the problem for which it was created. 2. Research should also consider not only today’s impacts but also reflect on the potential different innovations have for transforming markets at a later time—ultimately the most important question for understanding whether, and when, CSR initiatives might result in significant behavioral change. 3. In order to make practical important contributions, CSR scholars must place greater attention to building theory on causal mechanisms and the temporal logic of a range of firm-focused policy innovations. DISCLOSURE STATEMENT G. Auld is a member of the Forest Stewardship Council’s environment chamber. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank David Vogel, Jonathon Koppell, and participants at the January 2007 Yale workshop on corporate social responsibility. LITERATURE CITED 1. Vogel D. 2005. The Market for Virtue: The Potential and Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst. 2. Young OR. 1999. The Effectiveness of International Environmental Regimes: Causal Connections and Behavioral Mechanisms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 326 pp. 3. Levy DL, Newell PJ, eds. 2005. The Business of Global Environmental Governance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 430 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 4. Gunningham N, Grabosky PN, Sinclair D. 1998. Smart Regulation: Designing Environmental Policy. Oxford/New York: Clarendon/Oxford Univ. Press. 494 pp. 5. Porter ME, Van Der Linde C. 1995. Green and competitive: ending the stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 73:120–34 6. Esty DC, Winston AS. 2006. Green to Gold: How Smart Companies Use Environmental Strategy to Innovate, Create Value, and Build Competitive Advantage. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press. 366 pp. 7. Matten D, Moon J. 2008. ‘Implicit’ and ‘explicit’ CSR: a conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 33:404–24 8. Prakash A. 2000. Greening of the Firm: The Politics of Corporate Environmentalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. 181 pp. 9. Andrews RNL. 1998. Environmental regulation and business ‘self-regulation.’ Policy Sci. 31:177–97 10. Reinhardt F. 1999. Market failure and the environmental policies of firms. J. Ind. Ecol. 3:9–21 11. Portney PR. 2005. Corporate social responsibility: An economic and public policy perspective. In Environmental Protection and the Social Responsibility of Firms: Perspectives from Law, Economics, and Business, ed. BL Hay, RN Stavins, RHK Vietor, pp. 107–31. Washington, DC: Resour. Future 12. Prakash A, Potoski M. 2006. The Voluntary Environmentalists: Green Clubs, ISO 14001, and Voluntary Regulations. Cambridge, UK/New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. 211 pp. 13. Prakash A, Potoski M. 2007. Collective action through voluntary environmental programs: a club theory perspective. Policy Stud. J. 35:773–92 14. Lyon TP, Maxwell JW. 2007. Environmental public voluntary programs reconsidered. Policy Stud. J. 35:723–50 15. Besley T, Ghatak M. 2007. Retailing public goods: the economics of corporate social responsibility. J. Public Econ. 91:1645–63 16. Baron DP. 2001. Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 10:7–45 17. Prakash A. 2001. Why do firms adopt “beyond-compliance” environmental policies? Bus. Strategy Environ. 10:286–99 18. Kollman K, Prakash A. 2001. Green by choice: cross-national variations in firms’ responses to EMS-based environmental regimes. World Polit. 53:399–430 19. Rondinelli DA, Berry MA. 2000. Corporate environmental management and public policy: bridging the gap. Am. Behav. Sci. 44:168–87 20. Bullis C, Ie F. 2007. Corporate environmentalism. In The Debate over Corporate Social Responsibility, ed. S May, G Cheney, J Roper, pp. 321–35. Oxford/New York: Oxford Univ. Press 21. Bansal P, Hunter T. 2003. Strategic explanations for the early adoption of ISO 14001. J. Bus. Ethics 46:289–99 22. Hoffman AJ. 2001. Linking organizational and field-level analyses—the diffusion of corporate environmental practice. Organ. Environ. 14:133–56 23. Margolis JD, Walsh JP. 2003. Misery loves companies: rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 48:268–305 24. Fishman C. 2006. The Wal-Mart effect and a decent society: Who knew shopping was so important? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 20:6–25 25. Taylor JG, Scharlin PJ. 2004. Smart Alliance: How a Global Corporation and Environmental Activists Transformed a Tarnished Brand. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press. 278 pp. 26. Pedersen ER, Andersen M. 2006. Safeguarding corporate social responsibility in global supply chains: how codes of conduct are managed in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Public Aff. 6:228–40 27. De Tienne KB, Lewis LW. 2005. The pragmatic and ethical barriers to corporate social responsibility disclosure: the Nike case. J. Bus. Ethics 60:359–76 28. Bowd R, Bowd L, Harris P. 2006. Communicating corporate social responsibility: an exploratory case study of a major UK retail centre. J. Public Aff. 6:147–55 29. Iles A. 2007. Seeing sustainability in business operations: US and British food retailer experiments with accountability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 16:290–301 30. Doubleday R. 2004. Institutionalising nongovernmental organisation dialogue at Unilever: framing the public as ‘consumer-citizens.’ Sci. Public Policy (SPP) 31:117–26 www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 431 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 31. Werther WB Jr, Chandler DB. 2006. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 356 pp. 32. Paine L, Deshpande R, Margolis JD, Bettcher KE. 2005. Up to code. Harv. Bus. Rev. 83:122–33 33. Kolk A, Walhain S, Wateringen SVD. 2001. Environmental reporting by the Fortune Global 250: exploring the influence of nationality and sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 10:15–28 34. Bansal P, Roth K. 2000. Why companies go green: a model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 43:717 35. Cowan R. 1990. Nuclear-power reactors—a study in technological lock-in. J. Econ. Hist. 50:541–67 36. Gunningham N, Kagan RA, Thornton D. 2003. Shades of Green: Business, Regulation, and Environment. Stanford, CA: Stanford Law Polit. 37. Reinhardt FL. 1998. Environmental product differentiation: implications for corporate strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 40:43–73 38. Nehrt C. 1996. Timing and intensity effects of environmental investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 17:535–47 39. Ashman D. 2001. Civil society collaboration with business: bringing empowerment back in. World Dev. 29:1097–113 40. Hartman CL, Hofman PS, Stafford ER. 1999. Partnerships: a path to sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 8:255–66 41. Rondinelli DA, London T. 2003. How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Acad. Manag. Exec. 17:61–76 42. Livesey SM. 1999. McDonald’s and the environmental defense fund: a case study of a green alliance. J. Bus. Commun. 36:5–39 43. Constance DH, Bonanno A. 2000. Regulating the global fisheries: the World Wildlife Fund, Unilever, and the Marine Stewardship Council. Agric. Hum. Values 17:125–39 44. Auld G. 2006. Choosing how to be green: an examination of Domtar Inc.’s approach to forest certification. J. Strateg. Manag. Educ. 3:37–92 45. World Wide Fund. Nat. 2007. The Global Forest and Trade Network. Gland, Switz: WWF 46. Lang JT, Hallman WK. 2005. Who does the public trust? The case of genetically modified food in the United States. Risk Anal. 25:1241–52 47. Stafford ER, Hartman CL. 1996. Green alliances: strategic relations between businesses and environmental groups. Bus. Horiz. 39:50–59 48. Plummer J, Heymans C. 2002. Focusing Partnerships: A Sourcebook for Municipal Capacity Building in Public-Private Partnerships. London/Sterling, VA: Earthscan. 341 pp. 49. Börzel TA, Risse T. 2005. Public-private partnerships: effective and legitimate tools of transnational governance. In Complex Sovereignty: Reconstituting Political Authority in the 21st Century, ed. E Grande, LW Pauly, pp. 195–216. Toronto: Univ. Toronto 50. Linder SH. 1999. Coming to terms with the public-private partnership—a grammar of multiple meanings. Am. Behav. Sci. 43:35–51 51. Rosenau PV. 1999. Introduction—the strengths and weaknesses of public-private policy partnerships. Am. Behav. Sci. 43:10–34 52. Gentry B, Fernandez LO. 1997. Evolving public-private partnerships: general themes and lessons from the urban water sector. In OECD Workshop on Globalization and the Environment: New Challenges for the Public and Private Sectors. Paris: OECD 53. Warhurst A. 2005. Future roles of business in society: the expanding boundaries of corporate responsibility and a compelling case for partnership. Futures Ethical Corp. 37:151–68 54. Rittberger V. 2001. Global Governance and the United Nations System. Tokyo/New York: United Nations Univ. Press. 252 pp. 55. Khanna M. 2001. Non-mandatory approaches to environmental protection. J. Econ. Surv. 15:291–324 56. Carmin J, Darnall N, Mil-Homens J. 2003. Stakeholder involvement in the design of US voluntary environmental programs: Does sponsorship matter? Policy Stud. J. 31:527–43 57. Darnall N, Carmin J. 2005. Greener and cleaner? The signaling accuracy of U.S. voluntary environmental programs. Policy Sci. 38:71–90 58. Eisner MA. 2004. Corporate environmentalism, regulatory reform, and industry self-regulation: toward genuine regulatory reinvention in the United States. Governance 17:145–67 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 432 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 59. Arora S, Cason TN. 1996. Why do firms volunteer to exceed environmental regulations? Understanding participation in EPA’s 33/50 program. Land Econ. 72:413–32 60. Clinton B, Gore A. 1995. Reinventing Environmental Regulation. Washington, DC: Counc. Environ. Qual. 61. Borkey P, Glachant M, Leveque F. 1999. Voluntary Approaches for Environmental Policy: An Assessment. Paris: Organ. Econ. Coop. Dev. 62. Ruggie JG. 2004. Reconstituting the global public domain—issues, actors, and practices. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 10:499–531 63. Therien J-P, Pouliot V. 2006. The Global Compact: shifting the politics of international development? Glob. Gov. 12:55–75 64. Howlett M, Ramesh M. 2003. Studying Public Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. Toronto: Oxford Univ. Press 65. Percival RV, Schroeder CH, Miller AS, Leape JP. 2003. Environmental Regulation: Law, Science, and Policy. New York: Aspen. 1202 pp. 66. Prakash A. 2001. Why do firms adopt “beyond-compliance” environmental policies? Bus. Strategy Environ. 10:286–99 67. Arora S, Cason TN. 1995. An experiment in voluntary environmental regulation: participation in EPA’s 33/50 program. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 28:271–86 68. Bird LA. 2002. Understanding the environmental impacts of electricity: product labeling and certification. Corp. Environ. Strategy 9:129–36 69. Jordan A, Wurzel RKW, Zito A. 2005. The rise of ‘new’ policy instruments in comparative perspective: has governance eclipsed government? Polit. Stud. 53:477–96 70. Harrison K, Antweiler W. 2003. Incentives for pollution abatement: regulation, regulatory threats, and non-governmental pressures. J. Public Policy Anal. Manag. 22:361–82 71. Pearson R, Seyfang G. 2001. New hope or false dawn? Voluntary codes of conduct, labour regulation and social policy in a globalizing world. Glob. Soc. Policy 1:49–78 72. Willis A. 2003. The role of the global reporting initiative’s sustainability reporting guidelines in the social screening of investments. J. Bus. Ethics 43:233–37 73. Kollman K, Prakash A. 2002. EMS-based environmental regimes as club goods: examining variations in firm-level adoption of ISO 14001 and EMAS in UK, US, and Germany. Policy Sci. 35:43–67 74. Clapp J. 1998. The privatization of Global Environmental Governance: ISO 14000 and the developing world. Environ. Gov. 4:295–316 75. Bowers D. 2006. Making social responsibility the standard. Qual. Prog. 39:35–38 76. Castka P, Balzarova MA. 2008. The impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 on standardization of social responsibility—an inside perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. In press 77. Kolk A, van der Tulder R, Welters C. 1999. International codes of conduct and corporate social responsibility: Can transnational corporations regulate themselves? Transnatl. Corp. 8:143–80 78. Jenkins R. 2001. Corporate Codes of Conduct. Self-Regulation in a Global Economy. Geneva: UNRISD 79. Webb K. 2004. Understanding the voluntary codes phenomenon. In Voluntary Codes: Private Governance, the Public Interest, and Innovation, ed. K Webb, pp. 3–32. Ottawa, Can: Carleton Res. Unit Innov., Sci. Environ. 80. Fliess B, Gordon K. 2001. Better business behaviour. OECD Observer, Oct. 26, p. 53 81. Prakash A. 2000. Responsible care: an assessment. Bus. Soc. 39:183–209 82. Cashore B, Auld G, Newsom D. 2003. The United States’ race to certify sustainable forestry: non-state environmental governance and the competition for policy-making authority. Bus. Polit. 5:219–59 83. Carr CJ, Scheiber HN. 2002. Dealing with a resource crisis: regulatory regimes for managing the world’s marine fisheries. Stanford Environ. Law J. 21:45–79 84. Gardiner PR, Viswanathan KK. 2004. Ecolabelling and Fisheries Management. WorldFish Center Studies and Reviews 27. Penang, Malays.: WorldFish Cent. 44 pp. 85. King AA, Lenox MJ. 2000. Industry self-regulation without sanctions: the chemical industry’s Responsible Care Program. Acad. Manag. J. 43:698–716 86. Sasser EN. 2003. Gaining leverage: NGO influence on certification institutions in the forest products sector. In Forest Policy for Private Forestry, ed. L Teeter, B Cashore, D Zhang, pp. 229–44. Oxon, UK: CAB Int. www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 433 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 87. Garcia-Johnson R. 2001. Multinational corporations and certification institutions: moving first to shape a Green Global Production Context. Presented at the Int. Stud. Assoc. Conv., Chicago, 20–24 Febr. 88. Raynolds LT, Murray D, Heller A. 2007. Regulating sustainability in the coffee sector: a comparative analysis of third-party environmental and social certification initiatives. Agric. Hum. Values 24:147–63 89. Giovannucci D, Ponte S. 2005. Standards as a new form of social contract? Sustainability initiatives in the coffee industry. Food Policy 30:284–301 90. Daviron B, Ponte S. 2005. The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. London/New York: Zed Books 91. King A. 2007. Cooperation between corporations and environmental groups: a transaction cost perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32:889–900 92. Moffet J, Bregha F, MiddelKoop MJ. 2004. Responsible care: a case study of a voluntary environmental initiative. In Voluntary Codes: Private Governance, the Public Interest and Innovation, ed. K Webb, pp. 177– 207. Ottawa, Can: Carleton Unit Innov., Sci. Environ. 93. Equator Principles. 2008. Frequently asked questions about the equator principles. http://www.equatorprinciples.com/faq.shtml 94. Conroy ME. 2006. Branded: How the ‘Certification Revolution’ is Transforming Global Corporations. Gabriola Island, BC: New Soc. 335 pp. 95. Richardson BJ. 2005. The Equator Principles: the voluntary approach to environmentally sustainable finance. Eur. Environ. Law Rev. 14:280–90 96. OECD. 2000. The OECD declaration and decision on international investment and multinational enterprises. Paris: OECD 97. Wilkie C. 2004. Enhancing global governance: corporate social responsibility and the international trade and investment framework. See Ref. 99, pp. 288–322 98. Glob. Report. Initiat. 2008. Global Reporting Initiative. About GRI. http://www.globalreporting.org/ AboutGRI/ 99. Kirton JJ, Michael J, ed. 2004. Hard Choices, Soft Law: Voluntary Standards in Global Trade, Environment and Social Governance. Hants: Ashgate 100. Cashore B. 2002. Legitimacy and the privatization of environmental governance: how nonstate marketdriven (NSMD) governance systems gain rule-making authority. Governance 15:503–29 101. Cashore B, Auld G, Newsom D. 2004. Governing Through Markets: Forest Certification and the Emergence of Non-State Authority. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press 102. Bernstein S, Cashore B. 2007. Can nonstate global governance be legitimate? An analytical framework. Regul. Gov. 1:347–71 103. Bruce RA. 1998. The comparison of the FSC forest certification and ISO environmental management schemes and their impact on a small retail business. MBA thesis. Univ. Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 44 pp. 104. Moffat AC. 1998. Forest certification: an examination of the compatibility of the Canadian Standards Association and Forest Stewardship Council Systems in the maritime region. MES thesis. Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, Nova Scotia. 253 pp. 105. Overdevest C. 2004. Codes of conduct and standard setting in the forest sector—Constructing markets for democracy? Relat. Ind.-Ind. Relat. 59:172–97 106. Overdevest C. 2005. Treadmill politics, information politics and public policy—toward a political economy of information. Organ. Environ. 18:72–90 107. Fairtrade Label. Organ. 2008. Fairtrade producers. http://www.fairtrade.net/producers.html 108. Bartley T. 2003. Certifying forests and factories: states, social movements, and the rise of private regulation in the apparel and forest products fields. Polit. Soc. 31:1–32 109. Bartley T. 2007. Institutional emergence in an era of globalization: the rise of transnational private regulation of labor and environmental conditions. Am. J. Sociol. 113:297–351 110. Courville S. 2003. Social accountability audits: challenging or defending democratic governance? Law Policy 25:269–97 111. O’Rourke D. 2003. Outsourcing regulation: analyzing nongovernmental systems of labor standards and monitoring. Policy Stud. J. 31:1 112. Gulbrandsen LH. 2005. Mark of sustainability? Environment 47:8–23 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 434 Auld · Bernstein · Cashore Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. ANRV357-EG33-18 ARI 16 September 2008 0:0 113. Auld G, Balboa C, Bartley T, Cashore B, Levin K. 2007. The spread of the certification model: understanding the evolution of nonstate market driven governance. Presented at 48th Conv. Int. Stud. Assoc., Chicago, Illinois 114. ISEAL Alliance. 2006. ISEAL Code of Good Practice for Setting Social and Environmental Standards. London, UK: ISEAL Alliance 115. ISEAL Alliance. 2008. The ISEAL Alliance: Mission: History. London, UK: ISEAL Alliance 116. Rivera J, de Leon P. 2004. Is greener whiter? Voluntary environmental performance of western ski areas. Policy Stud. J. 32:417–37 117. Kimerling J. 2001. Corporate ethics in the era of globalization: the promise and peril of international environmental standards. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 14:425–55 118. Potoski M, Prakash A. 2005. Green clubs and voluntary governance: ISO 14001 and firms’ regulatory compliance. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49:235–48 119. Ronit K, Schneider V. 1999. Global governance through private organizations. Governance 12:243–66 120. Rivera J. 2004. Institutional pressures and voluntary environmental behavior in developing countries: evidence from the Costa Rican hotel industry. Soc. Nat. Resour. 17:779–97 121. Rivera J, De Leon P. 2005. Chief executive officers and voluntary environmental performance: Costa Rica’s certification for sustainable tourism. Policy Sci. 38:107–27 122. Howard-Grenville JA. 2006. Inside the “black box”—how organizational culture and subcultures inform interpretations and actions on environmental issues. Organ. Environ. 19:46–73 123. Reinhardt FL. 2000. Down to Earth: Applying Business Principles to Environmental Management. Boston, MA: Harv. Bus. Sch. Press. 291 pp. 124. Hall D, Lobina E. 2004. Private and public interests in water and energy. Nat. Resour. Forum 28:268–77 125. Tiffen P. 2002. A chocolate-coated case for alternative international business models. Dev. Pract. 12:383– 97 126. Bendell J. 2005. In whose name? The accountability of corporate social responsibility. Dev. Pract. 15: 362–74 127. Garvey N, Newell P. 2005. Corporate accountability to the poor? Assessing the effectiveness of community-based strategies. Dev. Pract. 15:389–404 128. Jenkins R. 2005. Globalization, corporate social responsibility and poverty. Int. Aff. 81:525–40 129. Lund-Thomsen P. 2005. Corporate accountability in South Africa: the role of community mobilizing in environmental governance. Int. Aff. 81:619–33 130. Palacios JJ. 2004. Corporate citizenship and social responsibility in a globalized world. Citizenship Stud. 8:383–402 131. Labuschagne C, Brent AC, van Erck RPG. 2005. Assessing the sustainability performances of industries. J. Cleaner Prod. 13:373–85 132. Vives A. 2004. The role of multilateral development institute in fostering corporate social responsiblity. Development 47:45–52 133. Graham D, Woods N. 2006. Making corporate self-regulation effective in developing countries. World Dev. 34:868–83 134. Frame B. 2005. Corporate social responsibility: a challenge for the donor community. Dev. Pract. 15:422– 32 135. Goddard T. 2005. Corporate citizenship: creating social capacity in developing countries. Dev. Pract. 15:433–38 136. Fair Labor Assoc. 2003. Fair labor association issues first public report; global companies go public with independent auditrs of labor practices in factories around the world. Washington, DC: Fair Labor Assoc. 137. Rodriguez-Garavito CA. 2005. Global governance and labor rights: codes of conduct and anti-sweatshop struggles in global apparel factories in Mexico and Guatemala. Polit. Soc. 33:203–33 www.annualreviews.org • The New Corporate Social Responsibility 435 AR357-FM ARI 22 September 2008 22:50 Annual Review of Environment and Resources Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. Contents Volume 33, 2008 Preface p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p pv Who Should Read This Series? p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p pvi I. Earth’s Life Support Systems Climate Modeling Leo J. Donner and William G. Large p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 1 Global Carbon Emissions in the Coming Decades: The Case of China Mark D. Levine and Nathaniel T. Aden p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p19 Restoration Ecology: Interventionist Approaches for Restoring and Maintaining Ecosystem Function in the Face of Rapid Environmental Change Richard J. Hobbs and Viki A. Cramer p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p39 II. Human Use of Environment and Resources Advanced Passenger Transport Technologies Daniel Sperling and Deborah Gordon p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p63 Droughts Giorgos Kallis p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p85 Sanitation for Unserved Populations: Technologies, Implementation Challenges, and Opportunities Kara L. Nelson and Ashley Murray p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 119 Forage Fish: From Ecosystems to Markets Jacqueline Alder, Brooke Campbell, Vasiliki Karpouzi, Kristin Kaschner, and Daniel Pauly p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 153 Urban Environments: Issues on the Peri-Urban Fringe David Simon p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 167 Certification Schemes and the Impacts on Forests and Forestry Graeme Auld, Lars H. Gulbrandsen, and Constance L. McDermott p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 187 vii AR357-FM ARI 22 September 2008 22:50 III. Management, Guidance, and Governance of Resources and Environment Decentralization of Natural Resource Governance Regimes Anne M. Larson and Fernanda Soto p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 213 Enabling Sustainable Production-Consumption Systems Louis Lebel and Sylvia Lorek p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 241 Global Environmental Governance: Taking Stock, Moving Forward Frank Biermann and Philipp Pattberg p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 277 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008.33:413-435. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by University of Waterloo on 09/26/20. For personal use only. Land-Change Science and Political Ecology: Similarities, Differences, and Implications for Sustainability Science B.L. Turner II and Paul Robbins p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 295 Environmental Cost-Benefit Analysis Giles Atkinson and Susana Mourato p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 317 A New Look at Global Forest Histories of Land Clearing Michael Williams p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 345 Terrestrial Vegetation in the Coupled Human-Earth System: Contributions of Remote Sensing Ruth DeFries p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 369 A Rough Guide to Environmental Art John E. Thornes p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 391 The New Corporate Social Responsibility Graeme Auld, Steven Bernstein, and Benjamin Cashore p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 413 IV. Integrative Themes Environmental Issues in Russia Laura A. Henry and Vladimir Douhovnikoff p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 437 The Environmental Reach of Asia James N. Galloway, Frank J. Dentener, Elina Marmer, Zucong Cai, Yash P. Abrol, V.K. Dadhwal, and A. Vel Murugan p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 461 Indexes Cumulative Index of Contributing Authors, Volumes 24–33 p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 483 Cumulative Index of Chapter Titles, Volumes 24–33 p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p 487 Errata An online log of corrections to Annual Review of Environment and Resources articles may be found at http://environ.annualreviews.org viii Contents