Module 5- British America 1700-1763

advertisement

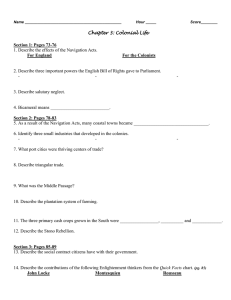

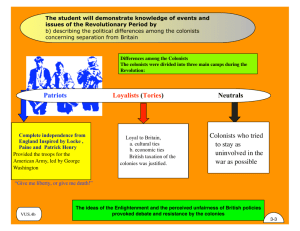

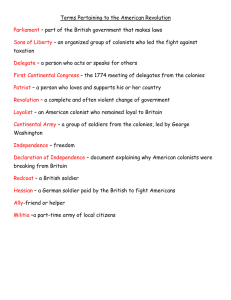

Module 5- British America 1700-1763 Topic Five Introduction The purpose of this lecture is to explain how British-Americans acquired another identity, that of Americans. At the start of the 18th century, the colonists were loyal subjects of the British crown, fully engaged in the British mercantile economy. By the end of the century, those colonists had become citizens of a new country, the United States of America. This lecture explores the revolutionary mentality fostered in the British colonists during the first half of the 18th century. There are several factors to consider when we think about British-America between 1700 and 1763. One is diversity. The colonies were heterogeneous: in ethnicity, religion, culture, social mores and economic systems. Second, all of the colonists were developing dual identities. They considered themselves to be British citizens, but they also increasingly thought of themselves as Americans. Finally, it would be a mistake to think of the colonies as unified. They were not. Instead, they were thirteen individual entities, with their own governing bodies, traditions, economies, histories, etc. That these colonies were able to unite in rebellion against their mother country in 1775 was, quite frankly, nothing short of remarkable. Society in British America During this time period, there was a population boom in the British colonies. Every twenty years the population doubled; in 1700 the number of colonists hovered around 250 thousand. By 1770, that number had increased to 2.2 million. Natural reproduction was largely responsible for this increase; over half the population was under the age of sixteen. Immigration also added to the population. The two most numerous groups to emigrate at this time were the Scots-Irish (Scots who were transplanted to Ireland) and Germans, both of whom settled in Pennsylvania. The Germans were mistakenly called the Pennsylvania Dutch because of the pronunciation used for their homeland. The increase in population, whether by natural means or immigration, will lead to further westward migration and further land ownership. Although the colonies had cities, British America was a rural society. About 5% of the population lived in cities, and no city had a population above 40k. Cities were commercial centers, not manufacturing centers (remember the Navigation Acts). The colonial cities did have urban craftsmen, such as blacksmiths, printers, brewers, tailors, etc. It is also in the cities where English culture was found. Major cities had theatres where English plays were produced or concerts were performed. English fashion was worn and English architecture prevailed. The British colonies did produce highly gifted artists, but they went to London in order to find patronage (see Benjamin West). Let's take a walk in the woods: At this time, there really wasn't any such thing as gallery showings for art (that is, if you wanted to sell it). Therefore, artists sought out wealthy (usually aristocratic) patrons who would commission pieces from the artists. All of the major colonial cities were port cities, and again, they were commercial centers where goods were shipped and received. Of colonial exports, 50% went to Britain, 30% went to the British colonies in the Caribbean and the remaining 20% was consumed or sold within the thirteen colonies. It was during this time period that the colonists started buying manufactured items from Britain, especially items such as cloth, tea, glass, glassware, pottery, sugar and furniture. Britain had begun her Industrial Revolution and was producing manufactured goods that were inexpensive to buy. American consumers stopped making homemade goods and started purchasing British manufactured items. It helped that British merchants offered Americans generous credit. By 1760, Americans were in debt to the British to the tune of two million pounds. 95% of Americans were engaged in some sort of farming. In the North, farmers engaged in a more diversified economy with family farms growing cereal crops as well as raising pigs and sheep. Pork was the staple protein of the American diet, along with game animals. Families in the North produced what they needed and also cultivated excess crops to sell. In the South, staple crops were grown, mainly cotton, but also tobacco, rice and indigo. These goods were exported to Britain. The Enlightenment Two social movements occurred during the 18th century that influenced Americans, fostered and independent spirit and planted seeds that would later lead to a revolution. One of these movements was intellectual, and the other was religious in nature. The first development we shall discuss is the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment was born out of the Scientific Revolution, which stated that the natural world, the physical world, ran according to a set of principles, i.e. laws that could NOT be broken. These laws governed everything; therefore, humans lived in a mechanistic and mathematically defined universe (the laws of physics are really just mathematical equations). For the first time, humans did not need a religious explanation of natural phenomena. Scientists such as Copernicus, Keppler, Galileo, Newton, Linnaeus, etc were formulating the natural laws of the universe. Enlightenment writers built upon the works of scientists of the Scientific Revolution. If there were natural laws that ran the universe, they reasoned, then there MUST be laws that apply to government/politics, economics, judicial systems, social systems, religion and so on. The creator (most Enlightenment writers were Deists) had equipped humans with the intellect to discover these laws. In the Enlightenment, there was no room for the superstitious, or the supernatural. In a mechanistic universe, the creator, having made his immutable laws, could not change them. Indeed, the creator was outside his creation and could not interfere or intervene directly (i.e. no miracles). It was the responsibility of humans to discover the creator's laws and implement them, thereby making the world the best of all places. Of course, the thinkers, writers and intellectuals of the Enlightenment had to figure out these laws, and they weren't always in agreement. Some of the principles that they did agree on, however, was the emphasis on logic, reason and order. There was no room for emotion in Enlightenment Europe. Furthermore, they rejected any supernatural explanation for any event. That being said, the Enlightenment in Europe affected only a very small portion of the population, namely the aristocracy and the middle class. The vast majority of Europe, peasant farmers, didn't give two shakes of a rat's behind about the best form of government or reform of the judicial system. It was Benjamin Franklin who imported the ideas of the Enlightenment into British-America. Franklin was a Philadelphia printer by trade, but he also was an inventor and scientist. He promoted lending libraries so that the general public would have access to books. Franklin sponsored a literary club in Philadelphia where educated gentlemen (i.e. the politically connected) could gather and read and discuss Enlightenment essays and books (remember Topic 4 and the social consequences of tobacco, coffee and sugar?). These literary clubs spread to other cities in the colonies. A few of the authors that these educated Americans studied were: John Locke, who wrote two influential books shortly after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. In one, Locke embraced empiricism, and stated that all humans entered the world a "tabula rasa" or blank slate (we would say notebook). Immediately, our experiences, taken in through our senses, started filling this notebook, making us the individual that we are today. Since we all enter the world "blank", then it makes sense that we are all born, or created, equal. Locke's second work stated that there was a "social contract" between authority and the people; furthermore, it was the responsibility of authority to serve the needs of the people. The people did not exist to serve the whims of authority. If authority, or government, broke the contract, then the people had the right to replace the government. Jean Jacques Rousseau, a Frenchman who advocated religious toleration, universal education and maintained that democracy was the best form of government. Baron de Montesquieu, another Frenchman who wrote a political treatise that argued for separation of powers. Of course, these great thinkers, among others, influenced the men who would establish the United States. The Great Awakening The Great Awakening was a religious event, in complete contrast to the Enlightenment, and as such there was tension between the two. In some ways, the Great Awakening was more important than the Enlightenment for it influenced more Americans than the latter. Americans, especially young Americans, had grown dissatisfied with the state of religion in the colonies. The spirituality and fervor of the early generation of colonists had given way to the pursuit of wealth. People were no longer concerned about their spiritual health. Furthermore, with more of the populace migrating westward and the population spreading out, the inhabitants on the frontier had less contact with organized churches. It was in this atmosphere that a new religious experience took place. Beginning in Massachusetts in the late 1730's, a Calvinist minister, Jonathan Edwards, reminded his congregation about predestination. His most famous sermon, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, was full of emotion and vivid imagery. Edwards exhorted the congregants to remember that salvation was not a matter of good works and church attendance. Instead, the individual took the responsibility of salvation into his/her own hands. How? By experiencing a public conversion, a "rebirth". Edwards wasn't the only minister preaching this new doctrine. George Whitfield, a circuit preacher, toured the colonies, spreading the word of personal salvation. What was the appeal of this new religious experience, especially to the younger generation of Americans? Well, for one thing, it wasn't boring. Great Awakening ministers preached in an emotional state, thundering at their congregation, reminding them of their sinful state. Conversely, ministers would cajole their charges to come before the whole church and be spiritually reborn, for there was no other way to redemption. These spiritual rebirths, enacted before the entire body of congregants, were not tame. To be fully reborn, a person had to fully open themselves to the Holy Spirit and be "overcome" by the violent emotions triggered by the rebirth. While being reborn, people would laugh, cry, sing, rave, roll on the floor, etc. In addition, this new way of worshipping required no education; no book learning. The road to salvation was through emotional and spiritual rebirth, not through study of the scripture. This made salvation available to more Americans, as the poorly educated and the illiterate now could hope to be saved. This doctrine also made the Great Awakening antithetical to the Enlightenment. The older, more conservative, members of the colonies were disdainful of this new style of preaching. They questioned if God really endorsed the Great Awakening. This older generation, known as the "Old Lights", as opposed to the "New Lights" of the Great Awakening, resented the disruption to their wellordered lives. The New Lights of the Great Awakening were extremely successful. Membership in their churches quadrupled. Princeton College was founded in 1747 by the New Lights to teach their doctrine. Let's take a walk in the woods: Shortly after Princeton was chartered, Brown (1764), Rutgers (1766), and Dartmouth (1768) were also established. Why were so many colleges founded in Colonial America (Yale and William and Mary were already up and running)? The answer is that the purpose of college was not to prepare young men for a career. Instead, young men went to college in order to train to become ministers. To that end, the curriculum would consist of Greek, Latin, theology, rhetoric, oratory, expository writing, maybe some history, etc. What was the result of the Great Awakening? It enhanced the American idea of individualism. Salvation was now in the hands of the individual; it was the responsibility of the person, not the church. Furthermore, the Great Awakening was democratic. It spread among urban and rural communities, to the rich and the poor, and to the settlers on the frontier. Preachers would "ride circuit" to frontier settlements to administer to the religious needs of those groups that were far from any organized church. The Great Awakening even spread through the slave communities of the South, trying to bring the hope of salvation to the Negros there. The Great Awakening also embraced religious toleration. To the New Lights, it didn't matter what church you worshipped in, as long as you were spiritually reborn and saved. This toleration allowed other churches to gain acceptance in British-America, most notably the Methodist and the Baptist (it was the Baptist preachers who infiltrated the South to try and convert and "save" the slaves there). Finally, the Great Awakening helped to create a common identity among the British colonists, who showed a willingness to defy traditional authority. That identity, of course, was American. A Century of Mercantile Warfare Beginning in 1688, Britain and France engaged in a series of economic wars in order to dominate global trade (mercantilism). Since the other European countries allied with the French (who were the world superpower at the time) or the British, these wars were, in actuality, the first world wars, At the same time, these wars spilled over to these countries' colonies in North and South America. The Europeans never thought that North/South America was important enough to commit an army to the defense of their colonists; therefore, the colonists engaged in battle themselves, most notably, the British-Americans and the French Canadiens. The British and French colonists were not trained in formal combat methods, or the rules of 18th century warfare. Instead, they practiced guerilla warfare. Fighting alongside the colonists were the native allies of the French and the British. The French Canadiens had a smaller population than British-America; approximately 55k colonists in 1750. Still, they only had two major cities in the north to protect, Quebec and Montreal. The Canadiens were also united under a single government. The British had a much larger population, but they were thirteen separate colonies, all with separate governments, armies, economies, and so forth. The British were also hemmed in by the French, who were located to the north in Canada, the west in the Ohio River Valley and continuing south into the Mississippi River Valley. A brief description of the mercantile wars of the time period will suffice. Keep in mind that these wars had a different name in North America than in Europe. The European name is given in parenthesis. King William's War 1689-1697 (War of the Grand Alliance) : British colonists with their Iroquois allies fought against the French Canadiens and the Huron. The war ended with the Treaty of Ryswick (1697), with neither side having gained anything. Queen Anne's War 1707-1713 (War of the Spanish Succession) : British colonists fought the French from South Carolina to New York. The war ended in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht and the British gained the French province of L'Acadie. They rename it Nova Scotia. Anne dies in 1714, leaving no living children to succeed her (even though she suffered through seventeen pregnancies). Her distant cousin, Prince George of Hanover, was chosen by Parliament to become George I of England (his mother Sophia was a granddaughter of James I). George, already a middle-aged man, packed up his family and moved to London. Back in North America, the Americans were concerned. The various conflicts with the French Canadiens had shown them the amount of land to be had beyond the tidewaters of the eastern seaboard. The problems was that the French explorers arrived there first and not only claimed Canada, but also the Ohio River Valley and the Mississippi River Valley. At the delta of the Mississippi River, the French colonists built their third major city, New Orleans. To put it another way, the British colonists were hemmed in by the French Canadiens. Since Spain was an ally with France, Georgia was founded as a buffer between South Carolina and Spanish Florida. King George's (II) War 1742-1748 (War of the Austrian Succession) : King George's war saw the first major fallout between the British and her colonists. In 1745, the Americans captured Ft. Louisbourg, located on an island in the middle of the Hudson River. Ft. Louisbourg guarded the approach to the St. Lawrence River and from there, the river route to Quebec and Montreal. This major victory wasn't capitalized upon, however. In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was signed and the Americans were forced to give Louisburg back to the French. Nevertheless, a year later, the Acadians of Nova Scotia were forcibly deported to Louisiana, where their descendents today are known as Cajuns. King George's War had a profound effect on the Americans. The colonists no longer had the singular goal of protecting their colonies; they also wanted to remove the French from western lands, especially the fertile Ohio River Valley. Moreover, control over western land meant lucrative trade deals with the natives. Albany Congress In 1754, British leaders, American delegates and the Iroquois Council met at Albany for the purpose of planning a strategy against the French. It was here at the Albany Congressthat Benjamin Franklin first proposed a plan of union; that all the colonies would unite into one single body. Both the British and the Americans rejected the idea out of hand: the colonies because they did not want to give up their power of taxation and Britain because one large colony could undermine "British rule" in North America. War of the Ohio Valley 1755: The French had built a string of defensive forts in the Ohio Valley, the most important of which was Fort Duchesne. Duchesne was located at the juncture of three rivers and guarded a strategic spot on the Ohio River. In 1754, a combined force of British and American forces attempted to capture Fort Duchesne, but failed. A young George Washington was part of this expedition. The French and Indian War 1756-1763 (Seven Year's War): The French and Indian War was the last of the mercantile wars between Britain and France and the most important. The British PM William Pitt believed that the war would be won in North America and the British actually sent an army to the thirteen colonies. Fort Louisburg was captured in 1758, opening the way to the St. Lawrence River. Quebec was captured in 1759 (see The Death of Wolfe by Benjamin West) and Montreal surrendered in 1760. After losing its two main cities in Canada, the French surrender and the Treaty of Paris 1763 officially ended the war. Let's walk in the woods: When you write about the Treaty of Paris, you must put a date after it. Why? There have been at least twenty peace treaties signed in Paris. There are probably more, but that's as many as I can come up with at four in the morning. The Treaty of Paris 1763 The treaty that ended the French and Indian War ended France's standing as the most powerful nation in the world and began Britain's dominance as the global superpower. All of French Canada was turned over to Britain; overnight 80k French Canadien citizens became subject to the British government. Parts of Spanish Florida were also turned over to Britain; in compensation, France signed over Louisiana, including New Orleans, to Spain. Britain gained an empire "upon which the sun never set". Results of the French and Indian War As stated before, the French and Indian War was the last of the mercantile wars. Britain emerged from the war as the dominant economic, military and political power. The treaty that ended the war also showed a shift in British economic policy; the British rejected the French sugar islands in the Caribbean for Canada. Instead of being trade oriented (mercantilism), the British are now interested in acquiring territory (empire building). The British also come out of the war hugely in debt and the government of Britain has to find a way to pay that debt. The Americans have some thinking to do also. First, they are now part of a vast empire and the Americans have to figure out their place in this new empire. Also, their greatest threat, the French, are now removed. The colonists are free to assess their relationship with their mother country. During the war, the colonists also gained military experience, which will be helpful in another decade or so. Briefly explain the dual nature of the colonists' British/American identity between the years of 1701 and 1763.