armstrong`s handbook

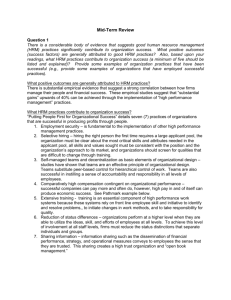

advertisement