Mr. Winschel Honors European History Period X

advertisement

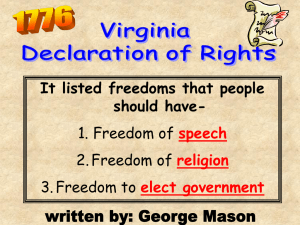

Mr. Winschel Honors European History Period X 11/25/2011 American Independence Day – July 4 Fireworks paint themselves upon the sky and across the land. Communities gather to view their respective versions of this same spectacle throughout the United States. It is like an overblown birthday party. And appropriately so, for that is what it is. The celebrations, individually and as a whole, commemorate the occasion of a single signature applied to a single piece of parchment over two hundred years ago. But with that signature and the 54 others that followed over the course of the next two months, a nation was born. The date is the fourth of July, American Independence Day. Each year the scene described above is repeated throughout the United States. Independence Day is a national holiday upon which most Americans do not work, and virtually all federal, state and local government buildings, services and offices shut down. In lieu of work, families and friends gather on this mid-summer day for parties and parades. Speeches and festivals mark the occasion, and red, white and blue banners and flags bespeckle the landscape. As dusk approaches, crowds flock to a central place to view the evening lightshow. Although most Americans have a fair understanding of why this holiday exists, even those who don’t know (or care) join in the jollity and merrymaking. Americans generally don’t require too great of an excuse to have a good time, and July Fourth is no exception. Nevertheless, the origins of this festive occasion provide all who are interested with a fascinating tale in themselves. The date was July 4, 1776. The setting was the town of Philadelphia in the burgeoning British colony of Pennsylvania. Following weeks of deliberation and debate, the delegates to what was called the Second Continental Congress, representing thirteen of Britain’s colonies along the eastern seaboard of North America, were to begin signing the Declaration of Independence. On July 2, a vote of the Congress declared the overwhelming desire of the thirteen colonies to sever all governmental ties with the mighty empire of Great Britain. It was a bold step for a land of 2.5 million people, no army or navy, and little manufacturing. For Great Britain, with her 12 million inhabitants, and a massive professional army and navy, had clearly established herself as the greatest power on Earth; she surely would not give up without a fight, the colonies that had provided her with so much of her wealth. In fact, the fighting was already a year old by the time the first signer of the Declaration, John Hancock, stepped forward on the morning of the Fourth of July. As if to mirror the audacity of the document itself, Hancock wrote his name boldly and large for all to see. With his signature, the American rebellion became the American War for Independence. A new nation (or more properly, thirteen new nations) sprung into existence, in the midst of a war to save its newborn life. The signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 is an event that has roots deep in the history of Great Britain; it has ramifications that continue to this day. The British colonies of North America sprung into existence during the Age of Discovery and Exploration that followed upon the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492. As Europe emerged from her period of isolation in the late Middle Ages, nation states emerged from the decaying feudal system. Each nation desired to increase its power and wealth. Expansion to the New World provided access to each goal simultaneously. Although Spain and Portugal jumped out to a head start in the race for colonies and territorial occupation in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the rest of Europe was quick to follow their lead. Of all the countries of Europe to send out missions of discovery and exploration, however, England proved to be the one that settled on those lands in the greatest proportions and with most lasting success. Having carved out a claim to land along the eastern coast of what is now the United States, she proceeded to settle and organize hundreds of thousands of her people on that land under thirteen distinct colonial governments. These, from Georgia in the south to Massachusetts Bay in the north, were the Thirteen Colonies. From the outset of this colonial venture, starting with Jamestown in 1607 and especially by the time of Plymouth Rock in 1620, the colonists and the monarch had divergent goals in settling the untamed wilderness of America. The colonists frequently fled to America for political or religious refuge, their ideas being out of sync with the British regime. Others came for personal economic gain or merely for adventure. Whatever the purpose of the colonists, the British crown consistently sought the financial advantage of England itself. In two things, however, the two were always and absolutely united. Each desired the success of the experiment (for they would each achieve their respective goals if success were had), and each one considered itself perfectly British. With this symbiotic relationship in mind, it seems odd that Independence Day would ever occur at all, let alone be celebrated. The largest single cause of the American Revolution and ultimately the Declaration of Independence was the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. From this worldwide conflict the British, along with her colonists in America, emerged victorious; but all at a price. For along with the former French possessions in the New World, Britain acquired from this war a massive debt. As a result of this debt, she determined on two fateful courses of action. 1) The colonists were to be made to help carry the load of debt, and 2) British troops were to be used to secure the boundaries of her colonies in order to prevent any future expensive hostilities. The cost of the latter was also to be borne by the colonists. As a consequence of these policies, the relationship between the colonies and Mother Country had changed. Under the mercantilist system, for 150 years the colonies had been treated as a source of raw materials for British factories and as a market for the sale of her finished goods. Taxes were levied in order to enforce cooperation with this policy. Although the colonists grew to resent this arrangement and frequently thwarted it by access to smugglers, they coped rather well in general. The British meanwhile, followed a policy of “Salutary Neglect” whereby they maintained a loose enforcement policy, overlooking many of the transgressions of the colonists. Economic gain rewarded everybody’s efforts. But with the debts incurred by the French and Indian War, this benign arrangement came to a screeching halt. In an effort to raise the money they so desperately needed, the British clamped down on smugglers and enforced the mercantilist laws with great severity. To these they added new taxes intended not merely to enforce mercantilism, but for revenue. These included the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, and the Tea Act. It was reasoned that by paying these modest taxes (the colonists at the time paid on average less than 5% of what people at home paid in taxes) the colonists would offset their portion of the costs associated with a war that they had started and from which they benefited. In addition, the Proclamation Line of 1763, the Quartering Act and others combined to limit the colonists’ access to the frontier and put British soldiers in their midst. Again, the idea was to protect the colonists from future costly wars at the borders, but again to be paid for by the colonists themselves. In each instance, the British colonists failed to be persuaded of the righteousness of the policy at hand. They saw each action as an infringement upon their rights as British subjects under the various documents comprising the British constitution. They saw the taxes not as mercantile taxes (to which they had tacitly agreed), but as revenue taxes (to which they had not). In order to have revenue taxes placed upon them, they demanded representation in the Parliamentary body that imposed them – another item viewed as a fundamental constitutional right. The cry, “No taxation without representation” rung throughout the colonies amidst spatterings of violence, boycotts, and massive propaganda campaigns run by idealists and smugglers who were organized and ever more firmly entrenched throughout the thirteen colonies. In loyal, if occasionally violent, submission, the colonists pleaded for the king’s intervention to set things aright, but to no avail. Finally, the Sons of Liberty, one of the more active of their organizations, resorted to terrorism. In the middle of the night, dressed as Indians, they dumped an entire shipload of tea into Boston’s harbor in 1774. It was the beginning of the end. The British reaction was terrible and swift. The Coercive Acts, which demanded repayment for the lost tea, shut down Boston Harbor and sent troops to live in the houses of the colonists, were followed by an order of Boston’s new military governor to arrest John Hancock and Sam Adams, two of the most notorious rabble-rousers. The troops sent to carry out this order were met by colonial militia at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. “The shot heard ‘round the world” in 1775 ignited a war that had no definite goal until July 2, or at latest July 4, 1776 when John Hancock signed his name on the Declaration of Independence. The ramifications of the signing of the Declaration of Independence proved to be nothing short of earth-shatteringly historic. After years of bloodshed, in 1783 King George III of Britain declared the thirteen colonies thenceforth free and independent. In the meantime, the colonies had formed a new nation called the United States of America. That nation came in time to dominate the entire mid-section of North America from Atlantic to Pacific Oceans. Today it is the most prosperous and highly-developed nation in the world, and the lone superpower. On July 4 every year, its people gather to celebrate its humble origins. But the Declaration of Independence and the American War for Independence did not occur in an Anglo vacuum. Indeed, they cannot be understood fully without examining the global context in which they occurred. The text of the Declaration makes this fact readily apparent. In writing the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson intended to tell the world not just that the colonies were severing ties with Great Britain, but also why. It was an effort to justify the very act of secession. He rested his case on appeals to British rights, but also on an appeal to universal natural rights. The former could have been an argument at just about any time after the creation of the English nation. The latter however was new and revolutionary in itself. Thomas Jefferson, like many of the founders, was imbued with the ideals of the Enlightenment, a philosophical movement that stressed such ideas as equality of men, natural rights, and government as deriving its powers from the consent of the governed. The predominantly French Enlightenment thinkers, men such as Rousseau, Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Diderot, wrote their greatest works during the 1700s. They wrote abstractly; Jefferson gave their ideas form in 1776, and a revolution was founded upon them. Dramatic as the ramifications of the Declaration were in America, they were massively felt worldwide as well. America set the example that revolutionary movements have followed to this day. With liberty and equality as motivation, revolution broke out in France in 1789, six years after America gained its freedom. From the seeds thus planted in France, liberal revolutions would criss-cross the entire continent of Europe throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, until monarchies perished everywhere. In 1945, Ho Chi Minh, the popular leader of Vietnamese anti-colonial forces, quoted from the US Declaration when declaring his country’s independence. The list could go on. The first shot of the American Revolution was called “the shot heard ‘round the world.” Given the universal effects of that shot, the title is apt. It is only appropriate that each July 4 in America one can hear the kaboom of fireworks and the crackle of firecrackers that indicate that that shot can be heard to this day as well. American Independence Day Survey of America from 15th to 18th century Mercantilism in the colonies French and Indian War and the Acts that followed Origins of American grievances with Britain Enlightenment and its pertinent ideas Bibliography “America’s Constitution – A Priceless Heritage of Humanitarianism.” American Journal 29 Dec. 2006 <http://www.polamjournal.com>. Bucki, Hon. Carl L. “The Constitution of May 3, 1791.” Info America 26 Dec. 2006 <http://info-america.buffalo.edu/classroom/constitution.html>. “Constitution of May 3, 1791.” America History 26 Dec. 2006 <http://www.americanhistoryrules.com/May_3>. Strybel, Robert. “Celebrating July 4th – a very American occasion.” American News 26 Dec. 2006. <http://www.Americannews.com>.