Chapter 16 Revision of the Fixed-Income Portfolio 1

advertisement

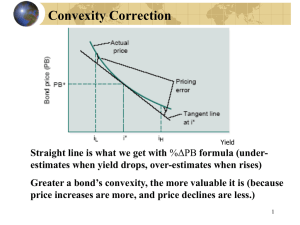

Chapter 16 Revision of the Fixed-Income Portfolio 1 There are no permanent changes because change itself is permanent. It behooves the industrialist to research and the investor to be vigilant. - Ralph L. Woods 2 Outline Introduction Passive versus active management strategies Bond convexity 3 Introduction Fixed-income security management is largely a matter of altering the level of risk the portfolio faces: • Interest rate risk • Default risk • Reinvestment rate risk Interest rate risk is measured by duration 4 Passive Versus Active Management Strategies Passive strategies Active strategies Risk of barbells and ladders Bullets versus barbells Swaps Forecasting interest rates Volunteering callable municipal bonds 5 Passive Strategies Buy and hold Indexing 6 Buy and Hold Bonds have a maturity date at which their investment merit ceases A passive bond strategy still requires the periodic replacement of bonds as they mature 7 Indexing Indexing involves an attempt to replicate the investment characteristics of a popular measure of the bond market Examples are: • Salomon Brothers Corporate Bond Index • Lehman Brothers Long Treasury Bond Index 8 Indexing (cont’d) The rationale for indexing is market efficiency • Managers are unable to predict market movements and that attempts to time the market are fruitless A portfolio should be compared to an index of similar default and interest rate risk 9 Active Strategies Laddered portfolio Barbell portfolio Other active strategies 10 Laddered Portfolio In a laddered strategy, the fixed-income dollars are distributed throughout the yield curve A laddered strategy eliminates the need to estimate interest rate changes For example, a $1 million portfolio invested in bond maturities from 1 to 25 years (see next slide) 11 Par Value Held ($ in Thousands) Laddered Portfolio (cont’d) 50000 45000 40000 35000 30000 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 Years Until Maturity 19 21 23 25 12 Barbell Portfolio The barbell strategy differs from the laddered strategy in that less amount is invested in the middle maturities For example, a $1 million portfolio invests $70,000 par value in bonds with maturities of 1 to 5 and 21 to 25 years, and $20,000 par value in bonds with maturities of 6 to 20 years (see next slide) 13 Par Value Held ($ in Thousands) Barbell Portfolio (cont’d) 50000 45000 40000 35000 30000 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 Years Until Maturity 19 21 23 25 14 Barbell Portfolio (cont’d) Managing a barbell portfolio is more complicated than managing a laddered portfolio Each year, the manager must replace two sets of bonds: • The one-year bonds mature and the proceeds are used to buy 25-year bonds • The 21-year bonds become 20-years bonds, and $50,000 par value are sold and applied to the purchase of $50,000 par value of 5-year bonds 15 Other Active Strategies Identify bonds that are likely to experience a rating change in the near future • An increase in bond rating pushes the price up • A downgrade pushes the price down 16 Risk of Barbells and Ladders Interest rate risk Reinvestment rate risk Reconciling interest rate and reinvestment rate risks 17 Interest Rate Risk Duration The increases as maturity increases increase in duration is not linear • Malkiel’s theorem about the decreasing importance of lengthening maturity • E.g., the difference in duration between 2- and 1-year bonds is greater than the difference in duration between 25- and 24-year bonds 18 Interest Rate Risk (cont’d) Declining interest rates favor a laddered strategy Increasing interest rates favor a barbell strategy 19 Reinvestment Rate Risk The barbell portfolio requires a reinvestment each year of $70,000 par value The laddered portfolio requires the reinvestment each year of $40,000 par value Declining interest rates favor the laddered strategy Rising interest rates favor the barbell strategy 20 Reconciling Interest Rate & Reinvestment Rate Risks The general risk comparison: Rising Interest Rates Falling Interest Rates Interest Rate Risk Barbell favored Laddered favored Reinvestment Rate Risk Barbell favored Laddered favored 21 Reconciling Interest Rate & Reinvestment Rate Risks The relationships between risk and strategy are not always applicable: • It is possible to construct a barbell portfolio with a longer duration than a laddered portfolio – E.g., include all zero-coupon bonds in the barbell portfolio • When the yield curve is inverting, its shifts are not parallel – A barbell strategy is safer than a laddered strategy 22 Bullets Versus Barbells A bullet strategy is one in which the bond maturities cluster around one particular maturity on the yield curve It is possible to construct bullet and barbell portfolios with the same durations but with different interest rate risks • Duration only works when yield curve shifts are parallel 23 Bullets Versus Barbells (cont’d) A heuristic on the performance of bullets and barbells: • A barbell strategy will outperform a bullet strategy when the yield curve flattens • A bullet strategy will outperform a barbell strategy when the yield curve steepens 24 Swaps Purpose Substitution swap Intermarket or yield spread swap Bond-rating swap Rate anticipation swap 25 Purpose In a bond swap, a portfolio manager exchanges an existing bond or set of bonds for a different issue 26 Purpose (cont’d) Bond swaps are intended to: • Increase current income • Increase yield to maturity • Improve the potential for price appreciation with a decline in interest rates • Establish losses to offset capital gains or taxable income 27 Substitution Swap In a substitution swap, the investor exchanges one bond for another of similar risk and maturity to increase the current yield • E.g., selling an 8% coupon for par and buying an 8% coupon for $980 increases the current yield by 16 basis points 28 Substitution Swap (cont’d) Profitable substitution swaps are inconsistent with market efficiency Obvious opportunities for substitution swaps are rare 29 Intermarket or Yield Spread Swap The intermarket or yield spread swap involves bonds that trade in different markets • E.g., government versus corporate bonds Small differences in different markets can cause similar bonds to behave differently in response to changing market conditions 30 Intermarket or Yield Spread Swap (cont’d) In a flight to quality, investors become less willing to hold risky bonds • As investors buy safe bonds and sell more risky bonds, the spread between their yields widens Flight to quality can be measured using the confidence index • The ratio of the yield on AAA bonds to the yield on BBB bonds 31 Bond-Rating Swap A bond-rating swap is really a form of intermarket swap If an investor anticipates a change in the yield spread, he can swap bonds with different ratings to produce a capital gain with a minimal increase in risk 32 Rate Anticipation Swap In a rate anticipation swap, the investor swaps bonds with different interest rate risks in anticipation of interest rate changes • Interest rate decline: swap long-term premium bonds for discount bonds • Interest rate increase: swap discount bonds for premium bonds or long-term bonds for shortterm bonds 33 Forecasting Interest Rates Few professional managers are consistently successful in predicting interest rate changes Managers who forecast interest rate changes correctly can benefit • E.g., increase the duration of a bond portfolio is a decrease in interest rates is expected 34 Volunteering Callable Municipal Bonds Callable bonds are often retied at par as part of the sinking fund provision If the bond issue sells in the marketplace below par, it is possible: • To generate capital gains for the client • If the bonds are offered to the municipality below par but above the market price 35 Bond Convexity The importance of convexity Calculating convexity General rules of convexity Using convexity 36 The Importance of Convexity Convexity is the difference between the actual price change in a bond and that predicted by the duration statistic In practice, the effects of convexity are minor 37 The Importance of Convexity (cont’d) The first derivative of price with respect to yield is negative • Downward sloping curves The second derivative of price with respect to yield is positive • The decline in bond price as yield increases is decelerating • The sharper the curve, the greater the convexity 38 The Importance of Convexity (cont’d) Bond Price Greater Convexity Yield to Maturity 39 The Importance of Convexity (cont’d) As a bond’s yield moves up or down, there is a divergence from the actual price change (curved line) and the duration-predicted price change (tangent line) • The more pronounced the curve, the greater the price difference • The greater the yield change, the more important convexity becomes 40 Bond Price The Importance of Convexity (cont’d) Error from using duration only Current bond price Yield to Maturity 41 Calculating Convexity The percentage change in a bond’s price associated with a change in the bond’s yield to maturity: dP 1 dP 1 d 2 P Error 2 dR 2 (dR ) P P dR 2 P dR P where P bond price R yield to maturity 42 Calculating Convexity (cont’d) The second term contains the bond convexity: 1 d 2P Convexity 2 (dR 2 ) 2 P dR 43 Calculating Convexity (cont’d) Modified duration is related to the percentage change in the price of a bond for a given change in the bond’s yield to maturity • The percentage change in the bond price is equal to the negative of modified duration multiplied by the change in yield 44 Calculating Convexity (cont’d) Modified duration is calculated as follows: Macaulay duration Modified duration 1 Annual yield to maturity / 2 45 General Rules of Convexity There are two general rules of convexity: • The higher the yield to maturity, the lower the convexity, everything else being equal • The lower the coupon, the greater the convexity, everything else being equal 46 Using Convexity Given a choice, portfolio managers should seek higher convexity while meeting the other constraints in their bond portfolios • They minimize the adverse effects of interest rate volatility for a given portfolio duration 47