Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation

advertisement

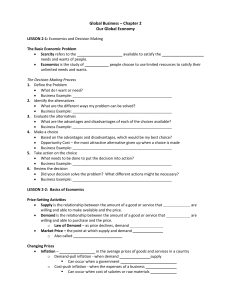

Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation Kyoji FUKAO (Hitotsubashi University and RIETI) May 20, 2014 Prepared for the RIETI World KLEMS Symposium Japan’s experience of the lost decades likely provides important lessons for the rest of the world currently characterized by “secular stagnation” (Summers 2013). Structure of Today’s Presentation 1. Japan's Current Economic Situation 2. Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation 2 (trillion yen per year) 550.0 % 9 525.0 8 Through the BOJ’s 500.0 massive stimulus 475.0 measures and active fiscal policies, Japan 450.0 finally appears to be 425.0 escaping from deflation. 400.0 (However, we need to 375.0 take account of the 350.0 “front‐loading” of 325.0 consumption prior to 300.0 the consumption tax 275.0 hike.) 7 6 5 GDP (in 2005 prices) 4 Potential GDP (in 2005 prices) 3 Inflation rate (CPI, right axis) 2 1 0 -1 -2 250.0 -3 1980/ 1- 3. 1981/ 1- 3. 1982/ 1- 3. 1983/ 1- 3. 1984/ 1- 3. 1985/ 1- 3. 1986/ 1- 3. 1987/ 1- 3. 1988/ 1- 3. 1989/ 1- 3. 1990/ 1- 3. 1991/ 1- 3. 1992/ 1- 3. 1993/ 1- 3. 1994/ 1- 3. 1995/ 1- 3. 1996/ 1- 3. 1997/ 1- 3. 1998/ 1- 3. 1999/ 1- 3. 2000/ 1- 3. 2001/ 1- 3. 2002/ 1- 3. 2003/ 1- 3. 2004/ 1- 3. 2005/ 1- 3. 2006/ 1- 3. 2007/ 1- 3. 2008/ 1- 3. 2009/ 1- 3. 2010/ 1- 3. 2011/ 1- 3. 2012/ 1- 3. 2013/ 1- 3. 2014/ 1- 3. 1. Japan's Current Economic Situation Sources: Cabinet Office and CPI Statistics. 3 From an I‐S balance viewpoint, the recovery in aggregate demand heavily relies on huge government deficits, which is not sustainable. Japan’s Saving‐Investment Balance: Relative to Nominal GDP (Four‐quarter Moving Average) % 35 30 25 20 15 10 Current account surplus Private gross saving Private gross investment Private surplus General government deficit 5 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 0 -5 Source: National Accounts. 4 Growth Strategy The present government is taking policies to overcome deflation and stimulate private investment through a reduction in real interest rates. However, limited investment opportunities and low rate of return on capital Extremely low or negative real interest rates are required Danger of bubbles For sustainable growth, need to raise rate of return on capital through productivity growth. Policies we need for productivity growth • • • • • Promotion of ICT and intangible investment. More rapid restructuring of firms left behind in innovation and internationalization, through M&A and other measures. Promotion of entrepreneurs and startups. Promotion of startup of domestic establishments by Japanese multinationals through improvement of regional logistics, FTAs, reduction of corporate taxes, etc.) Restructuring of the labor market (improvement of social safety net, enhancement of labor market liquidity, reduction of unfair gaps between regular and part‐time workers). Growth strategies are mainly drafted by ministries. Ministries are quite reluctant to reduce their regulations. No real change from the failed strategies 5 of the last two decades. The Risk of a Hard Landing is Rising According to recent estimates by the IMF, the combined negative GDP gap of 36 developed economies in 2014 is expected to be about $1.1 trillion (2.2% of their GDP). Japan’s current GDP gap is much closer to zero than that of many other developed economies. Through unconventional monetary policy, the BOJ has supplied huge amounts of high powered money and kept interest rates on long‐term government bonds close to zero. If inflation expectations spread, the BOJ will face a difficult policy decision: Keep interest rates low → further expansion of money supply, sharp depreciation of the yen, hyper inflation? Raise interest rates → Bond holders will incur huge capital losses, potential damage to financial system, deep recession? 6 2. Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation 1. Although it is important not to fall into the deflation trap, keeping real interest rates very low or negative through a zero nominal interest rate plus moderate inflation will not be sufficient for solving the fundamental problems. It is probably possible for economies to keep on growing by maintain high investment rates through low real interest rates. However, as capital accumulation continues, the rate of return on capital will decline, so that extremely Gross rate of return on capital (right axis) low or even negative real interest rates will be required. Yet, keeping very low or negative real interest rates, a positive inflation rate, and full Capital-GDP ratio (left axis) employment carries the danger of leading to new bubbles. Therefore, for growth to be sustainable, it is necessary to raise the rate of return on capital through productivity growth. 7 0.26 4.0 0.24 3.5 0.22 3.0 0.20 2.5 0.18 2.0 0.16 1.5 0.14 1.0 0.12 0.5 0.10 0.0 0.08 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 4.5 2. Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation (Contd.) 2. At least, in the case of Japan, the productivity growth slowdown seems to be caused not by an exogenous drying up of innovation (on this issue, see Gordon 2013), but by structural factors of the economy such as low intangible and ICT investment by small and medium‐sized firms, an inflexible labor market, etc., most of which could have been fixed through sensible policies. We need sensible and courageous The Relationship between Per Capita Gross policy makers, not fatalists. Prefectural Product and Social Capital Stock per Man-Hour Labor Input: 2008 Social capital stock per manhour labor input 3. The largest part of excess savings went to the government deficit. But most of the government expenditure was used in inefficient ways. We need to use public investment to enhance productivity growth. 0.8 -0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.3 -0.2 0.2 -0.4 -0.6 Gross prefectural product per capita 8 2. Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation (Contd.) 4. In the case of Japan, the decline in household saving was cancelled out by an increase in saving by large corporations. Large corporations – despite their high productivity – do not actively invest domestically and use their surplus funds not for capital investment or paying dividends but for debt repayment and the accumulation of liquid assets. Whether this kind of corporate saving behavior is desirable, and whether governance in major corporations functions properly, is an important research topic for the future. 30 25 20 Private savings total Corporate savings 15 10 5 Household savings 9 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 0 2. Lessons from Japan’s Secular Stagnation (Contd.) 5. Some countries, such as China and Germany, seem to be enjoying low real exchange rates and huge current account surpluses, and other economies suffer from that. On the other hand, many low‐income economies still want capital inflows. We need a fundamental reform of the international monetary system which will mitigate the scarcity of final demand in developed economies. 6. Japan’s negative GDP gap has almost disappeared. The risk that Japan provides another lesson, namely that exiting from unconventional policies is likely to entail a hard landing, is rising. 10