Immigration, Family Responsibilities and the Labor Supply of Skilled Native Women

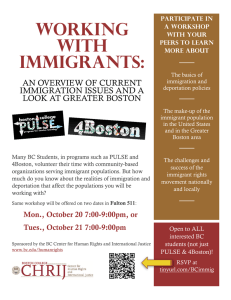

advertisement