Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference

advertisement

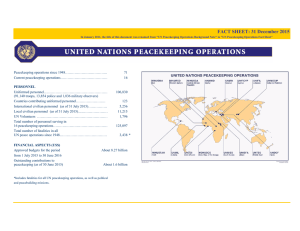

Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Improving the Quality of Peacekeeping Operations in Sub Saharan Africa through Media and Public Information Alexandre Essome, Emmanuel Innocents Edoun and Charles Mbohwa This study argues that a gap exists between information policy initiation by UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) Missions, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and those vested with the responsibility to discharge these functions in the field. Africa has been experiencing a number of conflicts since many countries gained independence from colonialism in the late 50s and early 60s. This situation has been of concern for the United Nations which has responded by deploying Peace Keeping missions to ease tensions within and among nations in Africa. To achieve their mission, UNDPKO Missions need effective public information. The quality of information received should be comprehensively explored and managed effectively during the operationalization of the Peace Keeping Missions in the affected areas. The overall objective in United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations management is to enhance the ability of the mission to fulfill its mandate successfully. Key strategic goals are to maintain the cooperation of the parties to peace processes, manage expectations of the population and donors, garner support for the operation among the local population, and secure broad international support , especially among Troops Contributing Countries (TCC’s) and Police Contributing Countries (PCC’s) and major donors. Using the qualitative research approach, this study seeks to understand the role of Media and Information as strategy in mitigating conflict in countries such are the DRC in order to facilitate socio-economic development. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to demonstrate that media and public information strategy are effective tools for improving the quality of peacekeeping operations in Sub-Sahara Africa through sound and effective managerial approaches during operations in affected areas. Key Words: Information Policy, United Nations, Peace Keeping Missions, Troup Contributing Countries, Police Contributing Countries 1. Introduction 1.1 Background and Justification After the Second World War that ended in 1945, the Marshall Plan was put in place to assist many European countries and allies that were severely damaged by the atrocities of the war. A number of decisions were therefore adopted by international organizations including the United Nations to facilitate Global Security. Many governments in the world have put tremendous efforts to eradicate poverty through conflict resolution related strategies and policies in order to secure socio-economic development for countries affected by years of civil wars and regional conflicts. Despite progress on several fronts, including at the United Nations and at the international financial institutions, developing policy for effective development and security engagement remains a challenge in both conceptual and operational terms – _______________________________________________ Alexandre Essome, Emmanuel innocents EDOUN, PhD and Charles Mbohwa School of Quality and Operations Management, University of Johannesburg, South Africa Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 not least because discussion of political, security, economic, and humanitarian issues traditionally has occurred in different multilateral fora, among different sets of stakeholders (CIC, 2015)1 CIC therefore argues that, coherent and integrated development, security and political support to countries emerging from conflict has proven difficult. Organizing the international response around early support to economic recovery, livelihoods, and services, and the core task of state building has proven a greater challenge. Core political, security, economic, and humanitarian tasks are carried out by an ad hoc and fragmented array of bilateral and multilateral development actors. Given this context, an effective media and public information strategy becomes critical and imperative not only to Mission leaders but also to all UN staff members assigned to the field. The men and women tasked with the peacekeeping duty need to be media savvy to be able to utilize available information channels to help promote peace and assist in the process leading to the return to democratic normalcy. This is central to provide the audiences and population with basic information because public information is expected to be at the centre of policy, planning and implementation. This research study will demonstrate that, although it is acknowledged that Public Information units existed and continue to exist in missions since 1989, in practice managers are yet to be trained and enabled to fully embrace the benefice of media as tools of promoting their work. Cases abound where managers failed to integrate public information strategy and view its approach as strategically irrelevant to conflict resolution. Faced with an environment of misunderstanding, public information officers are considered as “outsiders”, to be implicated only when a particular view of information is to be made public. If ever they are associated, it is to diminish the negative impact of poor decision making. More often than not, information strategy or a media plan is sought only after the situation has gotten worse and the urgent need of changing negative perception has worsened. Nations Peacekeeping Missions owes their legal birth to Security Council Resolutions (SCR). Once validated following a debate among the fifteen-member body in New York, it becomes a binding document, numbered and dated. What follows are steps of drafting the implementation framework by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) for managers and, a dispatch of teams of Experts to access the feasibility and the eventual formation of the Mission in the country or area affected. Africa counts close to nine United Nations out of eighteen that exist worldwide (UN Report, 2014). These Missions provide assistance and gateway in resolving conflicts for almost 300 million people in Africa. To establish the increasing role and impact of UN Missions in Africa, Sylvia UchennaAgu in an essay published by the British journal of Art and Sciences in 2013, quoted Huseyno (2008-2) description of the role played by the international community in maintaining global peace and security, as finding itself in a situation when it is the sole political actor able to stage the violence or break up the 1 Center on International Corporation (CIC) Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 deadlock and push further the peace process when local actors are unwilling or unable to reach agreement. 2. Review of related literature 2-1 Conceptual Framework This research is important in that, given the persistence of conflicts in the continent, both African and international organisations ought to reinforce axes of cooperation in order to create conducive environments where citizens could live in peace and vacate to their daily activities for socio-economic development. To support international treaties that protect citizens in conflict zones, governments involve should respect the basic principles of governance in order to ease. Also, governments could elaborate programmes to deal with political, operational and institutional challenges in order to ease the effective role of media and public information strategy in improving the quality of peacekeeping operations in Sub Saharan Africa. The model below is a typical demonstration of the author about the process involve in using media and critical information in solving problems arising in conflicts zones. This model is of the view that, socio-economic development can only happen if an organization such as MONUSCO receives the necessary information that will assist in operationalizing peace keeping missions strategies in conflict zones. However in order to achieve this, the mission needs to consider a number of challenges that are critical in paving way for a smooth transition. These include inter-alia, political, operational and institutional challenges Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Tool for Effective Strategy Media and Public Information Conflict Zones Conflict Zones Conflict zones Peace Keeping Operations SECURITY MONUSCO MONUSCO Socio-economic Development Source: Adapted from E.I EDOUN- (2015)- MONUSCO Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 2-2. Discussions around the role of Media and Communications in the Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) This Section is constructed around the role that Public Information (PI) tools play in Peace building processes. Since the first UN Mission that hosted PI offices in 1989 in Namibia, Missions now a day encompass various tools of communication to render effective their Public Information strategy. The Section will particularly insist on the role radio medium as he has proven to reach a vast array as well a variety of population groups. In MONUSCO, the biggest United Nations and the most expensive in the world, the Mission possesses all tools of communication to reach out to local population. In his analysis of the role of Media in Conflict Resolution highlighting the role of the United Nation Radio in the DRC, Essome, (2013) who participated in GLAFAD Conference at the Pan African Parliament in Midrand, Johannesburg, convincingly argued that, the role of media is very important in Peace Building Operations as it provides useful information that contribute to achieving the objective sought for by a Mission in securing and implementing the mandate of protecting civilian population. Highlighting the case of Radio Okapi in the DRC, The United Nations decided in 2002 to create its radio named OKAPI symbolizing the role this radio was going to play in attaining peace. The author was able to observe while working in MONUSCO that, Radio as a people medium of communication offers a forum for the search of lost ones following a conflict situation, particularly where people are massively displaced, radio can initiate cross cutting news reporting, builds bridges promoting positive relationship and creates programming such as open microphone dialogue between various segment of the public. Radio can convenes round table moderation with the aim to converge views and manage expectations. Furthermore radio programs in a conflict area can also bring about tolerance, actions of development and can encourage peaceful co-existence. Before analyzing in depth the role of various tools of communication in a conflict zone, lets understand some of the root causes of the conflict in the Great lakes regions, which playground is the Democratic republic of the Congo. 2.2.1 Overview of the Conflict in DRC Eastern DRC and others parts of the country to some extend have been a theatre of armed conflict almost continuously since 1996. That has led to material, physical destruction and loss of lives, but also a large displacement of people within the country and into the neighboring countries such as Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi. Further, the State limited ability to respond effectively and a ramping state of corruption have severely weakened the social contract with citizens leading to high level of mistrust and lack of confidence. The formation of M23 in March 2012 led to a further deterioration of security situation in the east. As government forces deployed to address the pressing situation of M23, other armed groups, notably FDLR, the ACPLS, the NDC of Tcheka, the Raya Mutomboki, and other Mayi Mayi groups, have opportunistically taken advantage of the situation and have gained control over part of the east. In the middle November Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 2012, intense fighting erupted between the newly formed movement of M23 and FARDC in Goma. This led the temporary control of Goma town by M23. This also led to a further deterioration of the humanitarian situation and an increase wave of criminality in major cities in the east, pillaging of material of the state services. The International community has to step up its support to DRC. All began with the regional players actions in Kampala, Uganda calling all sides to resume talks and to seek peaceful resolution of the conflict. The AU got involved with its got involved with Security commission and the SADC response. At this same time the UN was working over night to see to it that all initiatives produced results, tangibles results. The meeting of Addis Abeba was convened and gave birth to what is known today as PSC agreement signed by eleven heads of state. The UN Security Council a month later issues a resolution 2098 putting in place the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) with a more rebuts mandate to disarm, neutralize armed groups in the area. If this was not the first time that the International community flexed his muscle to support Congo, it was a turning point to that support. The ICGLR initiative, the SADC's one, the AU's and the UN initiatives in Addis Abeba, he multilateral efforts and the UNSC really provided the bedrock of the positive signs that are obtained in the field today. One thing that I can happily note is the article in Addis Abeba accord calling on all neighboring countries of DRC not to intervene any way shape or form in the conflict. While he can pleasing to see latest support of the international producing results for DRC, it is worth reminding ourselves that since 1999 in Lusaka when the AU and the UN convened all parties for dialogue, many have taken place since from Lusaka to Ethiopia, Tanzania, South Africa (Sun City - Pretoria) Paris and Belgium to provide a helping hands to Congolese to solve their differences. The latest is good step forward. But, it is also a reminder that the road ahead is still long and all necessary measures are to be maintained to ensure a long tern resolution of the conflict 2.2.2 Media and Conflict Transformation Mechanisms From the experience of observing media reporting in my area of responsibilities in North Kivu and others places, I have noticed that the interest of conventional media often works from the premise that conflict sells, and that peace is boring. Within this perspective, violence is explored in detail while initiatives to bring about peace are undervalued. As a conflict escalates, the media tends to run after the violence that ensues, counting casualties and measuring land that has been captured by a party to the conflict. In our view, this is choosing the low path to re- porting a conflict. Many media practitioners stop reporting on a violent conflict when one party defeats the other, but while relationships may have taken on a different form the underlying causes may not have been addressed. The current situation now in North Kivu may have provided the national Forces of DRC with some successes by recovering some major cities in Rutchuru including a logistical stronghold position of M23, but the underlying causes of the conflict remain Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 and calls for a media treatment of the information that is both current and provides understanding of how to best solve the issue for the long term. In DRC, this the position articulated by all Special Envoys in the region. From Mary Robinson to Russ Feingold and the EU, AU Special Envoys as well the Special representative e of the Secretary General in the country, Martin Koblers The media can promote peace or reinforce the divisions in a society. In many instances, it promotes division by emphasizing differences between the parties rather than searching out commonalities. By over- focusing on divisions, the conflict is portrayed as a sport or a boxing match, in which there are winners and losers. And, media becomes the referee counting points. At every stage of a conflict – mounting grievances, eruption of violence, transition, and consolidation of peace – the media plays an important role in influencing whether a society opts for violence or for peace. One key role played by the UN public information offices in the ground to suggest to media practitioners to pay particular attention to trending elements of a conflict and not to lose sight of the overall agenda, which is a sustainable peace for the people. I must admit that it is not always easy to impress upon media practitioners of these necessities. But, thing for sure a great number of them understanding, although caught up between the aspect news that sells and theta contributes to lasting actions of peace. Media today being a 24 hours cycle where breaking news is the dominating factor and analysis and in deep reporting have taken the second seat 2.2.3 Origin of Radio Okapi as a New Tool of Communication in Peacekeeping Operations So knowing what we know from what media can do to transform a conflict despite competing reporting news interest of the day. How radio Okapi came about and what was the underlying premise by the UN to take this decision to launch a radio in the area where a fully fledged conflict was underway? Oscar Bloh (2003) argued that an " individual or a community" cannot avoid conflict, but can prevent it to from erupting into violence". Bloh argument central argument rests on the assertion that, media is to play an instrumental role a preventing a conflict. In order to comprehend Blog argument, we must look back and refer to 1994 in Rwanda where a radio called " MilleCollines" played a negative role in contributing to the eruption of the genocide. Historically, radio Mille Collines was not the only radio who played such a negative role in the history. Stories about radio in Poland and radio Oasis in Denmark, whom in their own rights contributed to increase the hatred of group against the other. In the DRC case, the basis of the conflict was, among other, deriving its root causes around access to resources, social exclusion, unaddressed identity question and the lack of effective communication between those in the leadership and others segments of the society. Knowing that conflict is part of human nature, and that the very fact that conflict exists among us that should strive to do all possible to prevent and install mechanisms that can prevent including communicating. That kind of communication, Oscar Bloch called it in its book, “the vertical and the horizontal communications". Taking into account the communication that addresses the need of Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 the people by the leader‟s whiles people views are channeled to the top for policy orientation. It is in that prevailing lack of communication context that the Security Council visited in June 2001 the DRC, to better understand the dynamics of the conflict. The team quickly put they finger on the problem. they identified the absence of an effective tool of communication to help shape perceptions in the right direction and forge relationship that was broken since the eruption of the conflict in 1996, which led to the the partition of the country in three entities controlled by the ( RCD/MLC/GoDRC) The country abounded of citizens perceiving differently resources sharing in the society. Wrong or right, the perception being the way one view and interpret the world and reality, and many instances, is based on our values and experiences. The Congolese needed to reverse that sentiment of distrust of one another to a society reflective of values where people look at this sam direction having in mind the same perspective. Late that year, in one of the UN Security Council, the UN decides to give birth to a tool of communication in DRC that will unite parties and promote understanding of the cause of the conflict. A team of experts is dispatched in DRC to come and iron out details and launch the radio. Keywords: RCD (Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie), MLC ( Mouvement pour la Libération du Congo), Go DRC ( Gouvernement of DRC), MillesCollines ( Formerly a radio in Rwanda), 2.2.4 Radio Okapi Programming as a Stabilizing Factor and Driver of Press Freedom in DRC Since its inception in 25 February 2002, which date coincided with the launch of talks of reconciliation Congolese warring parties in Sun City, South Africa. Okapi opted for a holistic approach of communication by creating early shows (Dialogue entre Congolais) that opened the space for dialogue to a number of different levels of individuals in various controlled parts of the country in understanding each other and the root cause of their differences. The UN Radio also provided its facility for population who have not seen their love ones for year because of the war state and its displacement of the population to send searching messages through radio network to reinsure family members that their still alive. The technique was to use radio Okapi drop box in every offices of MONUC now MONUSCO around the country to leave messages signaling to family members around the country of their existence. As Okapi was growing its audience, the grid changed to respond to the need of the people and challenges of the moment. Programs reconciliation efforts, the tradition period with a government of one president and four vice presidents coming from rebel groups, the elaboration of the Constitution, the preparation of the referendum and its subsequent processes of its adoption, the preparation of the first democratic election of 2006 and the acceptation the elections results in the country was casting his first free and fair vote, the role of women were to play in the country, the Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 democratic functioning of the first elected government of the country and the need to build capacity to respond to the challenges of development. If there is a consensus that can be built around Okapi products to Congolese public, it is that Okapi sharpen Congolese appetite for political discussion. Since Okapi programming began, people felt freed to say what they wanted in the open forums. All this against years of dictatorship of former rulers of the country It is one thing to sharpen people political appetite, it is another to guide these freed energies into a political dialogue resulting in concrete measures. Recent products of Okapi such as “Parole au Auditeurs" (Open Microphone) with a guest specialist explaining the context and correcting misperceptions are what Okapi as the leader in the media market in DRC. Okapi reaches 21 million listeners and has about 36 transmitters around the country both in FM and short waves. The radio now provides an internet streaming to the Diaspora and interested parties around the world to tape in and keep abreast with news of back home. Almost 200 national and worked tirelessly to gather news product air aired it in the timely manner 2.2.5 Relevance of Media Development Regulation (MDR) and the Need of Communication Flow in Peacekeeping Environment Ayad Alawi, then Prime Minister of Iraq asked in question while answering a question of journalist opined that " I understand the need for indecent regulation of the media but who is going to control it?" his reaction was of a leader of many fragile states, technocratic solutions alone have not introduced sustainable governance reform processes. The overriding reason for this is that reform processes are implemented in complex, diverse, socio-economic and political environments where groups and individuals have competing interests. In this section we will look at MDR and the communication flow between relevant stakeholders. Due to years of poor governance in most countries emerging from conflict situation, the relationship between the state and its people is marked by deep mistrust in staterun institutions. When a country is preparing to move from violence to democracy the expectations for a peace dividend can be high. And due to both external and internal pressure for a „quick peace‟, reform processes are often out of touch with little consideration of the context. In DRC, attempts to reform the media landscape by the national government are yet to yield tangible results. These reforms failed so far to robustly bring about a media landscape where professionals and media operators can discharge their respective roles. In many develop countries, media is seeing as the 4th power of the people. Because information that is independent is considered the life oxygen of any society, particularly democratic society. Yet, if people are unaware of what is going on in their surrounding, and those in the leadership make decisions in the secret, citizens will not be able to contribute to challenges of the country. Nobel Prize holder, the Economist Amartya Sen said " I am not aware of serious famine in a country with democratic process and where the press is relatively freed, because the freedom of Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 the objective press allows a citizen to be reinsured and consequently to take necessary steps of its survival" Against this thinking, reform processes are intended to bring about change as a way of consolidating the peace. In the context of DRC, what is lacking is that the change agenda often becomes linked to political elites and their partners, which raises serious questions about national ownership. Consultation, in many instances, is more about rhetoric from the government to the population than it is about concrete actions to align diverse actors and voices with the process. This creates a lack of participation, leading to the unlikely that citizens will mobilize to demand accountability in the implementation of reform policies. UN and many others international partners in many of those countries have always argued for an increased role of media to mainstreaming the voices of multiple stakeholders in the reform process. Because governance reform requires time and has to address the structural conditions that gave rise to the conflict. Civil society, including the media, needs to be actively involved in monitoring the implementation of reform processes. Placing communication at the heart of governance reform processes is critical for the reform‟s success In clear what form or shape a media reform should look like in an emerging country from conflict/. What do we mean by media development and regulation? A Good way to look at it is through UNESCO‟s Media Development Indicators, against which the media landscape can be analyzed. The Media Development Indicators define a framework, within which the media can best contribute to, and benefit from, good governance and democratic development. UNESCO‟s Media Development Indicators: • A system of regulation conducive to freedom of expression, pluralism and diversity of the media • Plurality and diversity of media, a level economic playing field and transparency of ownership • Media as a platform for democratic discourse • Professional capacity building and supporting institutions that underpins freedom of expression, pluralism and diversity • Infrastructural capacity is sufficient to support independent and pluralistic media The subsequent relevant question would be why is necessary to regulate media? • Ensure quality of technical aspects and programming Allow for diversity of opinion and diversity of programming • Protect and promote local culture • Protect local cultural, moral, social and religious values • Promote a competitive environment • Protect minors from material that would harm them emotionally, psychologically or physically • Encourage technical developments: Digital broadcasting, Internet use and access, etc Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Allow me to end by saying that the question of sustainability of Okapi is something is being debated now in the UN. A resolution is yet to be reached. While waiting for a decision, it worth saying that a radio tool such as Okapi is continuing moving forward. It may not be in its current model supported by the UN but to become a private enterprise with the view of generating resources while at this same time continue to play its role of common ground media. For the immediate term following MONUSCO withdrawal, Okapi will not in the position to become a conventional media because of the he will lack necessary financing and will not survive in the current context media legislation in DRC without the legal backing of the United Nations I thanking for taking the time to listen to me understand the need for independent regulation of the media but I understand the need for independent regulation of the 3. Conclusion and Recommendations In addition to an increase in troop deployments, effective conduct of the use of force requires better intelligence, quick reaction capabilities, and force enablers, such as helicopters. However, the UN‟s ability to effectively increase missions‟ capacities is impacted by the prevailing economic environment and military overstretch both of which have caused governments to cut their defense budgets and UN contributions. Another impediment to operationalizing mission-wide preparedness for robust action is the lack of collective engagement in UN peacekeeping efforts. Given the heavy involvement of a limited set of troop contributors in current operations, it is unreasonable to expect the same countries to shoulder the burden of increased risks required when using force. However, Madlala-Routledge and Liebenberg (2004), argued that Africa needs a new “developmental peacekeeping” doctrine. They argue that the main drivers of conflict in Africa are resource-based and that an overly military approach to peacekeeping ought to be replaced by a more multidimensional, developmental approach. Elaborating on the nature of African conflicts, they convincingly explained that, a number of countries are becoming “war economies”, where the expulsion of populations, killing and large-scale human rights violations is a means of accumulating resources. The authors claim UN peacekeeping in Africa has largely ignored this dynamic. They offer „developmental peacekeeping‟ as an African alternative, defined as “postconflict reconstruction intervention which aims to achieve sustainable levels of human security through a combination of interventions aimed at accelerating capacity building and socio-economic development…”. On a practical level, this means African missions should be multi-disciplinary, with a mandate to conceptualizing an integrated post-conflict reconstruction programme that involves all parties, even if there is no cease fire. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 What many authors failed often to argue, it is the role people suffering should play in resolving the conflict. More often than not, proposition and strategies defining Mission implementation rely on the modus operandi that people ought to be told what to do when emerging from a conflict situation. The story is not told from people‟s perspective, but from the observers and others interested parties. Our view is that, if communicating if a two ways process, than Peacekeeping Missions and its officers assigned on the ground should take into account the story of the “Huntees” and improve intelling the story from the view of the “Hunters” as it is widely consigned a popular African‟s proverb. References: Albrecht S 2002, “Post-Conflict Peacebuilding and Second- Generation Preventive Action,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 2: 7-30. Alpaslan O 2002, “Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of former combatants in Afghanistan: Lessons learned from a cross-cultural perspective,” Third World Quarterly 23, no. 5: 961-975 Adekeye A 2002,Building Peace in West Africa: Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau Abiew FK 2003, “NGO- Military Relations in Peace Operations,” International Peacekeeping 10, no. 1: 24-39 Anika H 2002,From Congo to Kosovo: Civilian Police in Peace Operations. AstriSuhrke, Kristian Berg Harpviken, Arne Strand 2002, “After Bonn: Conflictual Peace Building,” Third World Quarterly 23(5): 875-891 Allan Gerson 2001, “Peace-Building: The Private Sector‟s Role,” American Journal of International Law 95(1):102-119 Amitav Acharya 2005, “Conclusion: Asian Norms and Practices in UN Peace Operations,” International Peacekeeping 12, no. 1: 146-151 AdekeyeAdebajo 2003, “In Search of Warlords: Hegemonic Peacekeeping in Liberia and Somalia”, International Peacekeeping, Vol. 10(4), pp. 62-81. Alex Bellamy and Paul Williams eds 2005,Peace Operations and Global Order. Alex J Bellamy and Paul Williams 2004, “Introduction: Thinking anew about peace operations,” International Peacekeeping 11(1), pp. 1-15 Alex J Bellamy 2004, “The „next stage‟ in peace operations theory,” International Peacekeeping 11 (1), pp. 17-38 Amalen du Misra 2004, “Rain on a parched land: reconstructing a post-conflict Sri Lanka,” International Peacekeeping 11(2): 271-288 Adekeye Adebajo and Ismail Rashid eds 2004, West Africa’s Security Challenges: Building Peace in a Troubled Region. Bolton, John R 2001, "United States Policy on United Nations Peacekeeping: Case Studies in the Congo, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia-Eritrea, Kosovo, and East Timor." 163 World Affairs 129 Bronwyn E and Roland B 2003, “NGOs and Reconstructing Civil Society in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” International Peacekeeping 10(1): 103-119 Barnett, M 1995, “The New United Nations Politics of Peace: From Juridical Sovereignty to Empirical Sovereignty”, Global Governance Vol. 1(1), pp. 79-97. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Brian U 1993, “For a UN Volunteer Military Force”, New York Review of Books, June 10, 1993 Berman E 2003, “The Provision of Lethal Military Equipment : French, UK, and US Peacekeeping Policies Toward Africa,” Security Dialogue 34(2): 199-214 Bernath, C and Sayre Nyce 2004, "A Peacekeeping Success: Lessons Learned from UNAMSIL." In International Peacekeeping: The Yearbook of International Peace Operations, vol. 8, Langholtz, Kondoch, and Wells eds (2004): 119-42. Boulden,J 2001, Peace enforcement: the United Nations experience in Congo, Somalia, and Bosnia. Bruce O 2004, “Model Codes for Criminal Justice and peace operations: some legal issues” 9(2) Journal of Conflict and Security Law 253. BuryJ 2003, “The UN Iraq-Kuwait Observation Mission,” International Peacekeeping 10(3): 71-88 Brendan O 2002, “The Future of UN Peacekeeping,” 25(2) Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 145 Bruce J 2002, “The Challenges of Strategic Coordination” in Stedman, Rothchild and Cousenseds, Ending Civil Wars, pp. 89-116. Briscoe N 2004,Britain and UN Peacekeeping: 1948-1967. Brayton S 2002, “Outsourcing war: mercenaries and the privatization of peacekeeping,” Journal of International Affairs 55, no. 2. Bullion.A 2001 “India and Sierra Leone: A Case of Muscular Peackeeping?,” International Peacekeeping 8, no. 4: 77-91. Chester C, Fen O H and Pamela Aeds, 2001, Turbulent Peace: the Challenge of Managing International Conflict Clapham, C 2002, "Problems of Peace Enforcement: Lessons to Be Drawn from Multinational Peacekeeping Operations in Ongoing Conflicts in Africa." In Africa in Crisis: New Challenges and Possibilities, ed. Tunde Zack-Williams, Diane Frost, and Alex Thomson, 196-215. Chris A 2002, “Making Old Soldiers Fade Away: Lessons from the Reintegration of Demobilized Soldiers in Mozambique,” 33(3) Security Dialogue 341. Christine, G 2001, “Peacekeeping after the Brahimi Report: Is There a Crisis of Credibility for the UN?”, Vol. 6(2) Journal of conflict and Security Law 267. Christine, G 2004,International Law and the Use of Force (2d ed.) Benjamin, R 2002, “Elections in Post-Conflict Scenarios: Constraints and Dangers,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 2: 118-139. Beatrice P 2002, “Building Peace in Situations of Post-Mass Crimes,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 2: 181-201. Chandra, LS 2004,Confronting Past Human Rights Violations: Justice vs Peace in Times of Transition. Operations,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 3: 51-66 Christopher, W 2005, “Post-Conflict Legal Education”, 10(1) Journal of Conflict and Security Law 101 Conflict Security and Development Group, King’s College London 2003,A Review of Peace Operations: A Case for Change. Diehl, PF 2002, “The Political Implications of Using New Technologies in Peace Operations,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 3:1-24 Donald, D 2002, “Neutrality, Impartiality and UN Peacekeeping at the Beginning of st the 21 Century,” International Peacekeeping 9(4), pp. 21-38 Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Donald, D 2003, “Neutral is not impartial: the confusing legacy of traditional peace operations”, 29(3) Armed Forces and Society 415. Donini, Antonio et al eds (2004),Nation-Building Unraveled?: Aid, Peace and Justice in Afghanistan Dallaire, R 2004,Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Dee, M 2001, “Coalitions of the Willing‟ and Humanitarian Intervention: Australia‟s David, C 2004, “The responsibility to protect? Imposing the „Liberal Peace‟,” International Peacekeeping 11(1): 59-81 Dyan M A and Jane P 2005,Gender, conflict and peacekeeping Dobson, H 2003,Japan and UN Peacekeeping: New Pressures and New Respons Dale, S 2005, “The Lawful Use of Force by Peacekeeping Forces: The Tactical Imperative,” International Peacekeeping 12, no. 2: 157-172 David, R S 2001, “Is a Peacekeeping Culture Emerging Among American Infantry in the Sinai MFO?,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 30, no. 5: 607-636 Dan S 2002, “Europe's peacebuilding hour? past failures, future challenges,” Journal of International Affairs 55, no. 2. David S. Sorensen and Pia Christina Wood eds.(2004), The Politics of Peacekeeping In the Post-cold War Era. Dipankar, B 2005, “Current Trends in UN Peacekeeping: A Perspective From Asia,” International Peacekeeping 12, no. 1: 18-33 Eric B 2003, “The provision of lethal military equipment: French, UK and US peacekeeping policies towards Africa”, 34(2) Security Dialogue 199. Edward, N 2002,“ „Transitional Justice‟: The Impact of Transnational Norms and the UN,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 2: 31-50. EsrefAksu 2004,The United Nations, Intra-State Peacekeeping and Normative Change Elizabeth, C and Chetan K eds 2001,Peacebuilding as Politics: Cultivating Peace In Fragile Societies. .Fleitz, F 2002,Peacekeeping Fiascoes of the 1990s: causes, solutions and US interests. Fund for Peace (2001),African Perspectives on Military Intervention Conference Summary Fund for Peace (2002a),Perspectives from the Americas on Military Intervention Conference Summary Fund for Peace (2002b),Perspectives from Asia on Military Intervention Conference Summary Fund for Peace (2003), Neighbors on Alert. Summary Report of the Regional Responses to Internal War Program Garland, HW 2005, Engineering Peace: The Military Role in Postconflict Reconstruction. Grist R 2001, “More than Eunuchs at the Orgy: Observation and Monitoring Reconsidered,” International Peacekeeping 8, no. 3: 59-78. Guehenno, JN 2002, “On the Challenges and Achievements of Reforming UN Peace Operations,” International Peacekeeping 9, no. 2: 69-80. Guehenno , J M 2003, “Everybody‟s Doing It,” World Today 59(8/9): 35-36