Divergent But Co-Existent: Local Governments and Tribal Governments Under the Same Constitution

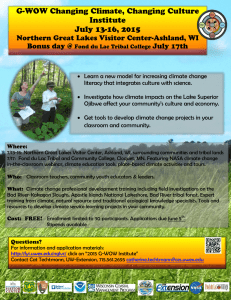

advertisement