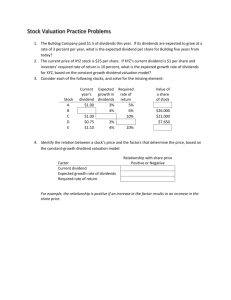

D : ISSECTING IVIDEND

advertisement