Document 12467048

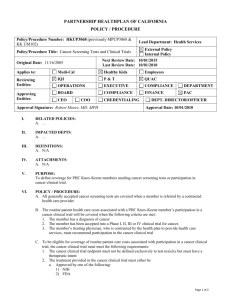

advertisement